Canine Status Epilepticus Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nietzsche and Psychedelics – Peter Sjöstedt-H –

Antichrist Psychonaut: Nietzsche and Psychedelics – Peter Sjöstedt-H – ‘… And close your eyes with holy dread, For he on honey-dew hath fed, And drunk the milk of Paradise.’ So ends the famous fragment of Kubla Khan by the Romantic poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He tells us that the poem was an immediate transcription of an opium-induced dream he experienced in 1797. As is known, the Romantic poets and their kin were inspired by the use of psychoactive substances such as opium, the old world’s common pain reliever. Pain elimination is its negative advantage, but its positive attribute lies in the psychedelic (‘mind- revealing’)1 state it can engender – a state described no better than by the original English opium eater himself, Thomas De Quincey: O just and righteous opium! … thou bildest upon the bosom of darkness, out of the fantastic imagery of the brain, cities and temples, beyond the art of Phidias and Praxiteles – beyond the splendours of Babylon and Hekatómpylos; and, “from the anarchy of dreaming sleep,” callest into sunny light the faces of long-buried beauties … thou hast the keys of Paradise, O just, subtle, and mighty opium!2 Two decades following the publication of these words the First Opium War commences (1839) in which China is martially punished for trying to hinder the British trade of opium to the Chinese people. Though opium, derived from the innocent garden poppy Papavar somniferum, may cradle the keys to Paradise it also clutches the keys to Perdition: its addictive thus potentially ruinous nature is commonly known. Today, partly for these reasons, opiates are mostly illegal without license – stringently so in their most potent forms of morphine and heroin. -

Comparison of Intranasal Versus Intravenous Midazolam for Management of Status Epilepticus in Dogs: a Multi-Center Randomized Parallel Group Clinical Study

Received: 16 July 2019 Accepted: 9 September 2019 DOI: 10.1111/jvim.15627 STANDARD ARTICLE Comparison of intranasal versus intravenous midazolam for management of status epilepticus in dogs: A multi-center randomized parallel group clinical study Marios Charalambous1 | Holger A. Volk2 | Andrea Tipold2 | Johannes Erath2 | Enrice Huenerfauth2 | Antonella Gallucci3 | Gualtiero Gandini3 | Daisuke Hasegawa4 | Theresa Pancotto5 | John H. Rossmeisl5 | Simon Platt6 | Luisa De Risio7 | Joan R. Coates8 | Mihai Musteata9 | Federica Tirrito10 | Francesca Cozzi10 | Laura Porcarelli11 | Daniele Corlazzoli11 | Rodolfo Cappello12 | An Vanhaesebrouck13 | Bart J.G. Broeckx14 | Luc Van Ham1 | Sofie F.M. Bhatti1 1Small Animal Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent University, Merelbeke, Belgium 2Department of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Hannover, Germany 3Department of Veterinary Medical Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy 4Department of Clinical Veterinary Medicine, Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University, Tokyo, Japan 5Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia 6Department of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 7Small Animal Referral Centre, Animal Health Trust, Newmarket, United Kingdom 8Department of Veterinary Medicine and Surgery, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 9Department of Clinical Veterinary -

The Following Studies Received Ethical Approval by Institutional And/Or National Review Committees If Appropriate

The following studies received ethical approval by institutional and/or national review committees if appropriate. Manchester AVA Spring Meeting April 2017 Cardiovascular findings during pre-anesthetic assessment in dogs undergoing two different pre-anesthetic assessment protocols and usefulness of the diagnostic tests performed S Diez-Bernal1, G Ortiz-Diez2, SP Monteagudo-Franco3, P Ruhi-Velasco4, C Garcia- Echarri4, A Perez-Higueras4, V Salazar-Nussio5. 1Anesthesia Service, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; 2Cardiology Service, Alfonso X El Sabio University, Madrid, Spain; 3Diagnostic Imaging Service, Alfonso X El Sabio University, Madrid, Spain; 4Alfonso X El Sabio University, Madrid, Spain; 5Anesthesia Service, Alfonso X El Sabio University, Madrid, Spain. The objectives of this study were to describe cardiovascular abnormalities (CVA) found during pre-anesthetic assessment in dogs in a veterinary teaching hospital and to evaluate the usefulness of the different diagnostic tests performed. One hundred and eight client-owned dogs underwent a basic pre-anesthetic assessment protocol including history, physical examination, hematology and biochemistry performed and evaluated by an anesthesia specialist; and a comprehensive pre-anesthetic assessment protocol that included, in addition to the tests performed in the basic assessment protocol, thoracic radiographs, ECG, and echocardiography evaluated by a licensed veterinarian. CVA were identified in twenty-five of ninety-seven dogs (25.8%) by cardiac auscultation; in 15 dogs (13.9%) by ECG; in 6 dogs (5.6%) by thoracic radiographs; and in 39 dogs (36.1%) by echocardiography (95% of which were diagnosed of chronic valvular heart disease, CVHD). Since CVHD was the cardiovascular condition that showed the highest prevalence, sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios of the other performed clinical tests were calculated for the diagnosis of this condition (taking echocardiography as gold standard). -

History Lectured on Midwifery at St Bartholomew’S Hospital and and Was in Attendance at the Births of All of Her Children

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2012; 42:274–9 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2012.317 © 2012 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Sir Charles Locock and potassium bromide MJ Eadie Honorary Research Consultant and Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Queensland, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Australia ABSTRACT On 12 May 1857, Edward Sieveking read a paper on epilepsy to the Correspondence to M Eadie Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society in London. During the discussion that Faculty of Health Sciences, followed Sir Charles Locock, obstetrician to Queen Victoria, was reported to have University of Queensland, Royal Brisbane and Women’s commented that during the past 14 months he had used potassium bromide to Hospital, Herston, successfully stop epileptic seizures in all but one of 14 or 15 women with ‘hysterical’ Brisbane 4029, Australia or catamenial epilepsy. This report of Locock’s comment has generally given him credit for introducing the first reasonably effective antiepileptic drug into medical Tel 61 2 (0)7 38311704 e-mail [email protected] practice. However examination of the original reports raises questions as to how soundly based the accounts of Locock’s comments were. Subsequently, others using the drug to treat epilepsy failed to obtain the degree of benefit that the reports of Locock’s comments would have led them to expect. The drug might not have come into more widespread use as a result, had not Samuel Wilks provided good, independent evidence for the drug’s antiepileptic efficacy in 1861. KEYWORDS Epilepsy treatment, Charles Locock, potassium bromide, Edward Sieveking, Samuel Wilks DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. -

Toxicological Review of Chloral Hydrate (CAS No. 302-17-0) (PDF)

EPA/635/R-00/006 TOXICOLOGICAL REVIEW OF CHLORAL HYDRATE (CAS No. 302-17-0) In Support of Summary Information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) August 2000 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC DISCLAIMER This document has been reviewed in accordance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency policy and approved for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Note: This document may undergo revisions in the future. The most up-to-date version will be made available electronically via the IRIS Home Page at http://www.epa.gov/iris. ii CONTENTS—TOXICOLOGICAL REVIEW for CHLORAL HYDRATE (CAS No. 302-17-0) FOREWORD .................................................................v AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, AND REVIEWERS ................................ vi 1. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................1 2. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL INFORMATION RELEVANT TO ASSESSMENTS ..... 2 3. TOXICOKINETICS RELEVANT TO ASSESSMENTS ............................3 4. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION ................................................6 4.1. STUDIES IN HUMANS - EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CASE REPORTS .................................................6 4.2. PRECHRONIC AND CHRONIC STUDIES AND CANCER BIOASSAYS IN ANIMALS ................................8 4.2.1. Oral ..........................................................8 4.2.2. Inhalation .....................................................12 4.3. REPRODUCTIVE/DEVELOPMENTAL STUDIES ..........................13 -

Rectal Absorption in Childhood

RECTAL ABSORPTION IN CHILDHOOD by JOHN WILLIAM ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, M.B., Ch. THESIS SUBMITTED FOR DEGREE OF M.D. UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW ProQuest Number: 13849818 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13849818 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 (i) CONTENTS Page Preface, ..« «». ••• ••• (ii) Introduction, ... ... ... 1. The Origins of Rectal Therapy, ... 1. The Present Position, ... ... 6. Investigation: A. The Absorption of Glucose, ... 11. Blood Sugar Studies, ... ... 15. The Glucose Content of the Rectal Washout. 18. The Effect of the Glucose Enema on Nitrogen Metabolism, ... ... 19. B. The Absorption of Sodium Chloride, ... 35. C. The Absorption of Predigested Protein, 41. D. The Absorption of Drugs, ... ... 53. 1. Potassium Bromide, ... ... 55. 2. Sodium Salicylate, ... ... 58. 3. Sulphanilamide, ... ... 65. Discussion. The Range of Substances Absorbed, ... 73. The Path of Absorption, ... ... 76. The Quantity Given, ... ... 80. General Conclusion, ... ... ... 84. General Summary, ... ... ... 86. APPENDIX. 1. Solutions used for Rectal Infusion, 87. 2. Biochemical Methods, ... 89. 3. Bibliography, ... ... 94. (ii) PREFACE The work for this thesis was carried out in the wards and biochemical laboratory of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow. -

Determination of Bromine Number According ASTM D 1159

SI Analytics-Application report Titration Determination of bromine number according ASTM D 1159 Description This application note describes the determination of the bromine number of petroleum distillates, olefins and similar samples with a bromine number > 1. For bromine numbers < 1 please use the test method for ASTM D 2710 or for aromatic hydrocarbons the coulometric test method ASTM D1492. Instruments Titrator TL 7000 or higher with 10 or 20 ml burette. Electrode Pt 1200, Pt 1400 or KF 1100 and temperature sensor (e.g. W W 5790 NN) Cable L 1 NN (only for Pt 1200 and Pt 1400) Stirrer Magnetic stirrer TM 235 Lab accessory Glass beaker 150 ml or larger with an ice bath or double jacketed titration vessel TZ 1756 with a cryostat. The sample have to be maintained at a temperature between 0 – 5 °C. 50 ml volumetric flask with stopper, 250 ml graduated measuring cylinder 5 ml volumetric pipette or variable one Magnetic stirrer bar 30 mm Reagents 1 Bromide-Bromate, Standard Solution(0.2500 M as Br2) 2 Glacial acetic acid 3 Dichloromethane (as replacement of 1,1,1-trichloroethane) 4 Methanol 5 Sodium thiosulfate solution 0.1 M for standardization of the titrant (optional) 7 Sulfuric acid 1/5 diluted (1 part H2SO4 conc. + 5 parts water) 6 Potassium Iodide solution (150 g/L) for standardization of the titrant (optional) 8 Starch indicator solution of redox electrode Pt 62 (+ WA 50 exchangeable unit) All reagents should be of analytical grade or better. Bromine number ASTM D 1159.docx 1/4 Titration procedure Titration solvent Prepare 1 L of titration solvent by mixing the following volumes of materials: 714 mL of glacial acetic acid, 134 mL of 1,1,1-trichloroethane (or better dichloromethane), 134 mL of methanol, and 18 mL of H2SO4(1 + 5). -

' -I {\~ 'Lr:R, ~', C, T...J5.--Ia. Rl V{. Rici-...L... FRENCH

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION MNH/83.7 ORGANISATION MONDIALE D! LA SANTE ..' ,I ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/ t) I'(.AA ... ) ' -I r:r, t......J5.--iA. rl V{. rICI-..... l... FRENCH {\~ ' l ~' , C, .. {.;'.; (,( 0 ' . \"'''-C:.. ~\ ~ ~v '- ' / '~ v- J C; SEVENTH REVIEW OF PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES FOR INTERNATIONAL CONTROL ) Geneva, 7-11 March 1983 " : CONTENTS INDEXED _, INTRODUCTION 1 SCOPE OF THE MEETING • 2 SOURCES AND NATURE OF DATA REVIEWED 2 REVIEW OF DRUGS FOR INTERNATIONAL CONTROL 2 i 4.1 Alfentanil 2 . 4.2 Chloral hydrate • 3 :4.3 Paraldehyde • • • 3 4.4 Potassium bromide 3 ' 4.5 Buprenorphine 3 ,4.6 Butorphanol • 4 4.7 Cyclazocine 4 4.8 Nalbuphine 4 4.9 Pentazocine • • • • 4 WHO'S CANCER PAIN RELIEF PROGRAMME 5 .; CONSIDERATIONS OF FUTURE PROGRAMMES • • • • 5 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS 6 ~~ EX I ...... 8 INTRODUCTION Dr Halfdan Mahler, Director-General of WHO, Dr Lu Rushan, Assistant tor-General of WHO, welcomed the participants in this meeting and expressed the concern of Tegarding the process of reviewing substances for international control. Dr Norman Sartorius, Director, Division of Mental Health WHO, discussed with the ipants the conditions in the developing nations which must be considered in reaching regarding the recommendation of substances for international control. He referred ifically to a gradual change in the attitude of people towards pain. No longer is pain as a natural accompaniment of disease. The effective analgesics, widely available the developed countries of the world, must become available for legitimate medical needs P~ tients in the developing countries. This availability of analgesic drugs must however into account the fact that many such substances are capable of producing dependence and • consequence significant public health and social problems. -

Studies on Isotope Separation of Lithium by Electromigration in Fused Lithium Bromide and Potassium Bromide Mixture, (II) Composition of Salt in Anode Compartment

Journal of NUCLEARSCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY,7 (10), p. 522~526 (October 1970). Studies on Isotope Separation of Lithium by Electromigration in Fused Lithium Bromide and Potassium Bromide Mixture, (II) Composition of Salt in Anode Compartment Yoshinobu YAMAMURA* and Shin SUZUKI* Received May 13, 1970 Accurate knowledge on the salt composition in the anode compartment is indispensable when 6Li is to be highly enriched by electromigration in fused LiBr-KBr mixture. A study was made on the dependence on temperature shown by the salt composition in the anode com- partment. It was observed that sustained electromigration led to a salt composition in the anode compartment that was determined by the prevailing temperature. The composition was observed for various temperatures between 380- and 740-C: In terms of the ratio Li/K in chemical equivalent, the values were 1.31 at 380-C, 1.29 at 420-C, 1.31 at 460-C, 1.41 at 500-C, 1.76 at 540-C, 1.82 at 580-C, 1.95 at 620-C, 2.16 at 680-C and 2.34 at 740-C. These results can be explained by assuming that the fused LiBr-KBr mixture is a system composed of two simple salts and their eutectic, and that at temperatures below 550-C, which is the melting point of LiBr, LiBr and KBr are dissolved in fused eutectic, while KBr is dissolved in the fused eutectic and LiBr at temperatures between 550- and 738-C, which latter is the melting point of KBr. I. INTRODUCTION . EXPERIMENTAL In a previous study(1), one of authors suc- 1. -

Chloral Hydrate

NTP TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE TOXICOLOGY AND CARCINOGENESIS STUDY OF CHLORAL HYDRATE (AD LIBITUM AND DIETARY CONTROLLED) (CAS NO. 302-17-0) IN MALE B6C3F1 MICE (GAVAGE STUDY) NATIONAL TOXICOLOGY PROGRAM P.O. Box 12233 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 December 2002 NTP TR 503 NIH Publication No. 03-4437 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Institutes of Health FOREWORD The National Toxicology Program (NTP) is made up of four charter agencies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS): the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health; the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), National Institutes of Health; the National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR), Food and Drug Administration; and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In July 1981, the Carcinogenesis Bioassay Testing Program, NCI, was transferred to the NIEHS. The NTP coordinates the relevant programs, staff, and resources from these Public Health Service agencies relating to basic and applied research and to biological assay development and validation. The NTP develops, evaluates, and disseminates scientific information about potentially toxic and hazardous chemicals. This knowledge is used for protecting the health of the American people and for the primary prevention of disease. The studies described in this Technical Report were performed under the direction of the NCTR and were conducted in compliance with NTP laboratory health and safety requirements and must meet or exceed all applicable federal, state, and local health and safety regulations. Animal care and use were in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Animals. -

Removal of Carbamazepine Onto Modified Zeolitic Tuff In

water Article Removal of Carbamazepine onto Modified Zeolitic Tuff in Different Water Matrices: Batch and Continuous Flow Experiments Othman A. Al-Mashaqbeh 1,* , Diya A. Alsafadi 2, Layal Z. Alsalhi 1, Shannon L. Bartelt-Hunt 3 and Daniel D. Snow 4 1 Emerging Pollutants Research Unit, Royal Scientific Society, Amman 11941, Jordan; [email protected] 2 Biocatalysis and Biosynthesis Research Unit, Royal Scientific Society, Amman 11941, Jordan; [email protected] 3 College of Engineering, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Omaha, NE 68583, USA; [email protected] 4 Water Sciences Laboratory, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Carbamazepine (CBZ) is the most frequently detected pharmaceutical residues in aquatic environments effluent by wastewater treatment plants. Batch and column experiments were con- ducted to evaluate the removal of CBZ from ultra-pure water and wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluent using raw zeolitic tuff (RZT) and surfactant modified zeolite (SMZ). Point zero net charge (pHpzc), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray fluorescence (XRF), and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) were investigated for adsorbents to evaluate the physiochemical changes resulted from the modification process using Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HDTMA-Br). XRD and FTIR Citation: Al-Mashaqbeh, O.A.; showed that the surfactant modification of RZT has created an amorphous surface with new alkyl Alsafadi, D.A.; Alsalhi, L.Z.; groups on the surface. The pHpzc was determined to be approximately 7.9 for RZT and SMZ. The Bartelt-Hunt, S.L.; Snow, D.D. results indicated that the CBZ uptake by SMZ is higher than RZT in all sorption tests (>8 fold). -

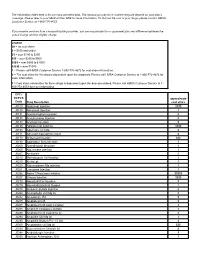

CPT / HCPCS Code Drug Description Approximate Cost Share

The information listed here is for our most prevalent plan. The amount you pay for a covered drug will depend on your plan’s coverage. Please refer to your Medical Plan GTB for more information. To find out the cost of your drugs, please contact HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-776-4672. If you receive services from a nonparticipating provider, you are responsible for a copayment plus any difference between the actual charge and the eligible charge. Legend $0 = no cost share $ = $100 and under $$ = over $100 to $250 $$$ = over $250 to $500 $$$$ = over $500 to $1000 $$$$$ = over $1000 1 = Please call HMSA Customer Service 1-800-776-4672 for cost share information. 2 = The cost share for this drug is dependent upon the diagnosis. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-772-4672 for more information. 3 = Cost share information for these drugs is dependent upon the dose prescribed. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1- 800-772-4672 for more information. CPT / HCPCS approximate Code Drug Description cost share J0129 Abatacept Injection $$$$ J0130 Abciximab Injection 3 J0131 Acetaminophen Injection $ J0132 Acetylcysteine Injection $ J0133 Acyclovir Injection $ J0135 Adalimumab Injection $$$$ J0153 Adenosine Inj 1Mg $ J0171 Adrenalin Epinephrine Inject $ J0178 Aflibercept Injection $$$ J0180 Agalsidase Beta Injection 3 J0200 Alatrofloxacin Mesylate 3 J0205 Alglucerase Injection 3 J0207 Amifostine 3 J0210 Methyldopate Hcl Injection 3 J0215 Alefacept 3 J0220 Alglucosidase Alfa Injection 3 J0221 Lumizyme Injection 3 J0256 Alpha 1 Proteinase Inhibitor