A Philippine Case Study. Environmental Management 2013, 51(6), 1236–1246

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird List Column A: We Should Encounter (At Least a 90% Chance) Column B: May Encounter (About a 50%-90% Chance) Column C: Possible, but Unlikely (20% – 50% Chance)

THE PHILIPPINES Prospective Bird List Column A: we should encounter (at least a 90% chance) Column B: may encounter (about a 50%-90% chance) Column C: possible, but unlikely (20% – 50% chance) A B C Philippine Megapode (Tabon Scrubfowl) X Megapodius cumingii King Quail X Coturnix chinensis Red Junglefowl X Gallus gallus Palawan Peacock-Pheasant X Polyplectron emphanum Wandering Whistling Duck X Dendrocygna arcuata Eastern Spot-billed Duck X Anas zonorhyncha Philippine Duck X Anas luzonica Garganey X Anas querquedula Little Egret X Egretta garzetta Chinese Egret X Egretta eulophotes Eastern Reef Egret X Egretta sacra Grey Heron X Ardea cinerea Great-billed Heron X Ardea sumatrana Purple Heron X Ardea purpurea Great Egret X Ardea alba Intermediate Egret X Ardea intermedia Cattle Egret X Ardea ibis Javan Pond-Heron X Ardeola speciosa Striated Heron X Butorides striatus Yellow Bittern X Ixobrychus sinensis Von Schrenck's Bittern X Ixobrychus eurhythmus Cinnamon Bittern X Ixobrychus cinnamomeus Black Bittern X Ixobrychus flavicollis Black-crowned Night-Heron X Nycticorax nycticorax Western Osprey X Pandion haliaetus Oriental Honey-Buzzard X Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard X Pernis celebensis Black-winged Kite X Elanus caeruleus Brahminy Kite X Haliastur indus White-bellied Sea-Eagle X Haliaeetus leucogaster Grey-headed Fish-Eagle X Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

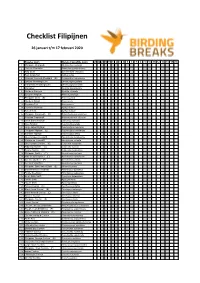

Checklist Filipijnen

Checklist Filipijnen 26 januari t/m 17 februari 2020 Engelse naam Wetenschappelijke naam 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 1 Philippine Megapode Megapodius cumingii 2 Chinese Francolin Francolinus pintadeanus 3 King Quail Excalfactoria chinensis 4 Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus 5 Palawan Peacock-Pheasant (E) Polyplectron napoleonis 6 Spotted Whistling Duck Dendrocygna guttata 7 Wandering Whistling Duck Dendrocygna arcuata 8 Garganey Spatula querquedula 9 Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata 10 Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope 11 Philippine Duck (E) Anas luzonica 12 Northern Pintail Anas acuta 13 Eurasian Teal Anas crecca 14 Common Pochard Aythya ferina 15 Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula 16 Philippine Frogmouth (E) Batrachostomus septimus 17 Palawan Frogmouth Batrachostomus chaseni 18 Great Eared Nightjar Lyncornis macrotis 19 Grey Nightjar Caprimulgus jotaka 20 Large-tailed Nightjar Caprimulgus macrurus 21 Philippine Nightjar (E) Caprimulgus manillensis 22 Savanna Nightjar Caprimulgus affinis 23 Grey-rumped Treeswift Hemiprocne longipennis 24 Whiskered Treeswift Hemiprocne comata 25 Grey-rumped Swiftlet (E) Collocalia marginata 26 Ridgetop Swiftlet (E) Collocalia isonota 27 Pygmy Swiftlet (E) Collocalia troglodytes 28 Philippine Swiftlet (E) Aerodramus mearnsi 29 Whitehead's Swiftlet (E) Aerodramus whiteheadi 30 Ameline Swiftlet (E) Aerodramus amelis 31 Germain's Swiftlet Aerodramus germani 32 Philippine Spine-tailed Swift (E) Mearnsia picina 33 Brown-backed Needletail Hirundapus giganteus 34 Purple Needletail Hirundapus celebensis -

Ultimate Philippines

The bizarre-looking Philippine Frogmouth. Check those eyes! (Dani Lopez-Velasco). ULTIMATE PHILIPPINES 14 JANUARY – 4/10/17 FEBRUARY 2017 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO This year´s Birdquest “Ultimate Philippines” tour comprised of the main tour and two post-tour extensions, resulting in a five-week endemics bonanza. The first three weeks focused on the better-known islands of Luzon, Palawan and Mindanao, and here we had cracking views of some of those mind-blowing, world´s must-see birds, including Philippine Eagle, Palawan Peacock-Pheasant, Wattled Broadbill and Azure- breasted Pitta, amongst many other endemics. The first extension took us to the central Visayas where exciting endemics such as the stunning Yellow-faced Flameback, the endangered Negros Striped Babbler or the recently described Cebu Hawk-Owl were seen well, and we finished with a trip to Mindoro and remote Northern Luzon, where Scarlet-collared Flowerpecker and Whiskered Pitta delighted us. 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Philippines www.birdquest-tours.com Our success rate with the endemics– the ones you come to the Philippines for- was overall very good, and highlights included no less than 14 species of owl recorded, including superb views of Luzon Scops Owl, 12 species of beautiful kingfishers, including Hombron´s (Blue-capped Wood) and Spotted Wood, 5 endemic racket-tails and 9 species of woodpeckers, including all 5 flamebacks. The once almost impossible Philippine Eagle-Owl showed brilliantly near Manila, odd looking Philippine and Palawan Frogmouths gave the best possible views, impressive Rufous and Writhed Hornbills (amongst 8 species of endemic hornbills) delighted us, and both Scale-feathered and Rough-crested (Red-c) Malkohas proved easy to see. -

Ultimate Philippines Tour Report 2015

The stunning –and endemic- Azure-breasted (Steere´s) Pitta showed exceedingly well several times during the tour. And they were the “real” thing, wild birds in the forest and no “tame”, staked-out birds at feeding stations (Dani Lopez-Velasco). ULTIMATE PHILIPPINES 18 JANUARY – 7 / 13 FEBRUARY 2015 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO This year´s Ultimate Philippines tour was yet again another highly successful tour to this avian endemic paradise. The first three weeks focused on the better-known islands of Luzon, Palawan and Mindanao, and here we saw some of those mind-blowing, world´s must-see birds, including Philippine Eagle, Palawan Peacock-Pheasant, Azure-breasted Pitta and Luzon Bleeding-heart (singing from a branch!), amongst many other endemics. The extension took us to the central Visayas where exciting endemics such as Negros Striped Babbler or the recently described Cebu Hawk-Owl were seen well. Our success rate with the endemic targets – the ones you come here for- was overall very good, and highlights included no less than 12 species of owl recorded, including mega views of Philippine Eagle-Owl, 11 species of beautiful kingfishers, including Hombron´s (Blue-capped Wood) and Spotted Wood and the 5 possible endemic 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Philippines 2014 www.birdquest-tours.com racket-tails. Odd looking Philippine and Palawan Frogmouths gave the best possible views, impressive Rufous and Writhed Hornbills (amongst 7 species of endemic hornbills) delighted us, and both Scale- feathered and Rough-crested (Red-c) Malkohas proved easy to see. A pair of Ashy Ground Thrushes were seen at point blank range, skulking Falcated and Striated Wren-Babblers were lured into view, an amazing male Celestial Monarch, getting very rare these days, was seen nicely after a lot of effort, together with Short-crested Monarch, and the rare White-fronted Tit gave also prolonged scope views as it sang from a dead snag. -

A Review of the Recent Advances in the Systematics of the Avian Superfamily Sylvioidea

Chinese Birds 2013, 4(2):99–131 REVIEW DOI 10.5122/cbirds.2013.0016 A review of the recent advances in the systematics of the avian superfamily Sylvioidea Per ALSTRÖM 1,2,, Urban OLSSON 3, Fumin LEI 1 1 Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China 2 Swedish Species Information Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Box 7007, SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden 3 Systematics and Biodiversity, Department of Biology and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Box 463, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Abstract The systematics of the avian superfamily Sylvioidea are reviewed, focusing on studies of relationships among families and within genera, more superficially on taxonomic studies at the species level. For the families Bernieridae and Phylloscopidae, new analyses based on already published sequence data are presented. Our understanding of relationships has been vastly improved in recent years due to a large number of molecular studies. However, the relationships among the different families remain largely obscured, probably mainly as a result of rapid divergence of the different primary lineages (families). Also, species level taxonomy has been much improved in recent years due to a large number of studies applying molecular markers and/or vocalizations and other life-history data. It seems likely that the number of species will continue to increase, as new groups are being studied with modern integrative methods. Keywords phylogenetic relationships, superfamily Sylvioidea, taxonomy Introduction tanagers, wood-warblers, and icterids). Subsequent studies of DNA sequence data have indicated that both The Passerida was identified by Sibley and Ahlquist Muscicapoidea and Passeroidea, after minor taxonomic (1990) based on DNA-DNA hybridization studies as adjustments, can be recovered as monophyletic (Barker the largest radiation within oscine passerine birds (cf. -

Comprehensive Phylogeny of the Laughingthrushes and Allies (Aves, Leiothrichidae) and a Proposal for a Revised Taxonomy

Received: 13 February 2018 | Revised: 10 April 2018 | Accepted: 1 May 2018 DOI: 10.1111/zsc.12296 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Comprehensive phylogeny of the laughingthrushes and allies (Aves, Leiothrichidae) and a proposal for a revised taxonomy Alice Cibois1 | Magnus Gelang2 | Per Alström3,4,5 | Eric Pasquet6 | Jon Fjeldså7 | Per G. P. Ericson8 | Urban Olsson9 1Natural History Museum of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland 2Göteborgs Naturhistoriska Museum, Göteborg, Sweden 3Department of Ecology and Genetics, Animal Ecology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 4Swedish Species Information Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden 5Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 6UMS MNHN/CNRS 2700 Outils et Méthodes de la Systématique Intégrative (OMSI) and UMR7205 Institut de Systématique, Evolution, Biodiversité CNRS MNHN UPMC EPHE, Sorbonne Universités, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France 7Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, Zoological Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark 8Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden 9Department of Zoology, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden Correspondence Alice Cibois, Natural History Museum Abstract of Geneva, CP 6434, CH 1211 Geneva 6, DNA phylogenies have gradually shed light on the phylogenetic relationships of the Switzerland. large babbler group. We focus in this study on the family Leiothrichidae (laughingth- Email: [email protected] rushes and “song babblers”), which represents the largest clade of babblers in terms Funding information of species diversity. Our phylogeny includes all genera and 82% of the recognized Swedish Research Council, Grant/Award Number: 621-2007-5280 and 2015- species, using mitochondrial and nuclear loci. -

A Comprehensive Molecular Phylogeny of Afrotropical White-Eyes

Journal Pre-proofs A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of Afrotropical white-eyes (Aves: Zosteropidae) highlights prior underestimation of mainland diversity and complex colonisation history Frederico C. Martins, Siobhan C. Cox, Martin Irestedt, Robert P. Prŷs-Jones nvestigation, Julia J. Day PII: S1055-7903(20)30115-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106843 Reference: YMPEV 106843 To appear in: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Received Date: 16 September 2019 Revised Date: 7 April 2020 Accepted Date: 16 April 2020 Please cite this article as: Martins, F.C., Cox, S.C., Irestedt, M., Prŷs-Jones nvestigation, R.P., Day, J.J., A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of Afrotropical white-eyes (Aves: Zosteropidae) highlights prior underestimation of mainland diversity and complex colonisation history, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (2020), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106843 This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Elsevier Inc. Running title: Molecular phylogeny of Afrotropical Zosteropidae A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of Afrotropical white-eyes (Aves: Zosteropidae) highlights prior underestimation of mainland diversity and complex colonisation history Frederico C. -

Molecular Systematics of the Avian Superfamily Sylvioidea with Special Regard to the Families Acrocephalidae and Locustellidae

Molecular systematics of the avian superfamily Sylvioidea with special regard to the families Acrocephalidae and Locustellidae (Aves: Passeriformes) I n a u g u r a l d i s s e r t a t i o n zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald vorgelegt von Silke Fregin geboren am 22.05.1976 in Werneck Greifswald, Juni 2012 2 Dekan: Prof. Dr. Klaus Fesser 1. Gutachter : Prof. Dr. Gabriele Uhl 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Staffan Bensch Tag der Promotion: 14.11.2012 3 4 Table of contents Table of contents Zusammenfassung..........................................................................................................................................7 Summary...........................................................................................................................................................9 Abbreviations................................................................................................................................................11 1 General Introduction.....................................................................................................................................13 1.1 DNA-DNA hybridisation studies.........................................................................................................13 1.2 Advantages and disadvantages of DNA sequences..........................................................................14 1.3 Analysis of DNA sequences..................................................................................................................15 -

Conservation Milestones of the Critically Endangered Philippine Crocodile (Crocodylus Mindorensis Schmidt 1935)

SYLVATROP Editorial Staff Bighani M. Manipula, PhD Melanie N. Ojeda Editor-in-Chief Editorial Assistant Adreana Santos-Remo Marilou C. Villones Managing Editor Circulation Officer/Proofreader Liberty E. Asis Eduardo M. Tolentino Adreana Santos-Remo Catalina DM. Aldemita Editors Gino S. Laforteza Circulation Assistants Maria Lourdes Q. Moreno, PhD Guest Editor Liberato A. Bacod Printing Supervisor January - June 2018 Vol. 28 No. 1 SYLVATROP, The Technical Journal of Philippine Ecosystems and Natural Resources is published by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) through the Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau (ERDB), College, Laguna. Sylvatrop is listed in Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters) Master Journal List. Subscription rates: Php75 for single issue copy (local); Php150 for combined issues and US$15 per single issue copy (foreign) excluding airmail cost; US$30 for combined issues. Re-entered as Second Class Mail CY 2018 at the College, Laguna Post Office on 23 March 2018. Permit No. 2018-21. Address checks to Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau c/o ERDB Circulation. For contributions or inquiries, address it to The Editor-in-Chief at the following address: SYLVATROP, The Technical Journal of Philippine Ecosystems and Natural Resources Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau, DENR Tel. No. (049) 557-1758 Fax: (049) 536-2850 E-mail address: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: sylvatrop.denr.gov.ph Cover Photo: The cover photo shows the species [Buceros hydrocorax, Gallirallus calayanensis, Prionailurus bengalensis heaneyi, Pithecophaga jefferyi, Pteropus pumilus, Otus megalotis, Crocodylus mindorensis (top to bottom)] included in the articles focusing on species conservation. Photo Credit: R. Sta. -

Remote Philippines

This stunning Whiskered Pitta was, not surprisingly, one of the best birds of the tour. (All photos by DLV, Irene Dy and Brad Hacker). REMOTE PHILIPPINES 3 – 20 / 28 FEBRUARY 2020 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO and IRENE DY With more and more birds being split and ‘available’ in the Philippines, we have resurrected our Remote Philippines tour to give us a great shot at finding a good number of endemics not available on our Classic Philippines tour. The two dovetail perfectly and together really do form the Ultimate Philippines tour. Focusing mostly on the Visayas, Mindoro, the more remote areas of Luzon, followed by a Panay and Tablas extension, the tour was never about a big species total, but purely about seeing those important birds. In total we recorded around 220 species (including half a dozen distinct allospecies), a high percentage of which were ‘diamond’ birds. These included some truly spectacular species, including the gorgeous Whiskered Pitta, which bounded around us at close range, and the critically endangered and very rarely seen Negros Bleeding-heart! Other stunners included the delightful little Negros Scops Owl, the cracking and difficult to find Visayan Broadbill, which we saw just when we were about to leave Bohol, lovely Camiguin, Mindoro, Cebu and Romblon Hawk-Owls, exquisite Dimorphic Dwarf and Northern Silvery Kingfishers, the incomparable Flame-breasted Fruit Dove, the very rare Isabela Oriole, the endangered Walden´s Hornbill and the skulking Bicol Ground Warbler that ran around our feet on our last attempt, to name just a few! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Remote Philippines 2020 www.birdquest-tours.com The incomparable Flame-breasted Fruit Dove that showed so well along Infanta Road.