Table of Small Business Size Standards Matched to North American Industry Classification System Codes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compilers & Translator Writing Systems

Compilers & Translators Compilers & Translator Writing Systems Prof. R. Eigenmann ECE573, Fall 2005 http://www.ece.purdue.edu/~eigenman/ECE573 ECE573, Fall 2005 1 Compilers are Translators Fortran Machine code C Virtual machine code C++ Transformed source code Java translate Augmented source Text processing language code Low-level commands Command Language Semantic components Natural language ECE573, Fall 2005 2 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 1 Compilers & Translators Compilers are Increasingly Important Specification languages Increasingly high level user interfaces for ↑ specifying a computer problem/solution High-level languages ↑ Assembly languages The compiler is the translator between these two diverging ends Non-pipelined processors Pipelined processors Increasingly complex machines Speculative processors Worldwide “Grid” ECE573, Fall 2005 3 Assembly code and Assemblers assembly machine Compiler code Assembler code Assemblers are often used at the compiler back-end. Assemblers are low-level translators. They are machine-specific, and perform mostly 1:1 translation between mnemonics and machine code, except: – symbolic names for storage locations • program locations (branch, subroutine calls) • variable names – macros ECE573, Fall 2005 4 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 2 Compilers & Translators Interpreters “Execute” the source language directly. Interpreters directly produce the result of a computation, whereas compilers produce executable code that can produce this result. Each language construct executes by invoking a subroutine of the interpreter, rather than a machine instruction. Examples of interpreters? ECE573, Fall 2005 5 Properties of Interpreters “execution” is immediate elaborate error checking is possible bookkeeping is possible. E.g. for garbage collection can change program on-the-fly. E.g., switch libraries, dynamic change of data types machine independence. -

Chapter 2 Basics of Scanning And

Chapter 2 Basics of Scanning and Conventional Programming in Java In this chapter, we will introduce you to an initial set of Java features, the equivalent of which you should have seen in your CS-1 class; the separation of problem, representation, algorithm and program – four concepts you have probably seen in your CS-1 class; style rules with which you are probably familiar, and scanning - a general class of problems we see in both computer science and other fields. Each chapter is associated with an animating recorded PowerPoint presentation and a YouTube video created from the presentation. It is meant to be a transcript of the associated presentation that contains little graphics and thus can be read even on a small device. You should refer to the associated material if you feel the need for a different instruction medium. Also associated with each chapter is hyperlinked code examples presented here. References to previously presented code modules are links that can be traversed to remind you of the details. The resources for this chapter are: PowerPoint Presentation YouTube Video Code Examples Algorithms and Representation Four concepts we explicitly or implicitly encounter while programming are problems, representations, algorithms and programs. Programs, of course, are instructions executed by the computer. Problems are what we try to solve when we write programs. Usually we do not go directly from problems to programs. Two intermediate steps are creating algorithms and identifying representations. Algorithms are sequences of steps to solve problems. So are programs. Thus, all programs are algorithms but the reverse is not true. -

Scripting: Higher- Level Programming for the 21St Century

. John K. Ousterhout Sun Microsystems Laboratories Scripting: Higher- Cybersquare Level Programming for the 21st Century Increases in computer speed and changes in the application mix are making scripting languages more and more important for the applications of the future. Scripting languages differ from system programming languages in that they are designed for “gluing” applications together. They use typeless approaches to achieve a higher level of programming and more rapid application development than system programming languages. or the past 15 years, a fundamental change has been ated with system programming languages and glued Foccurring in the way people write computer programs. together with scripting languages. However, several The change is a transition from system programming recent trends, such as faster machines, better script- languages such as C or C++ to scripting languages such ing languages, the increasing importance of graphical as Perl or Tcl. Although many people are participat- user interfaces (GUIs) and component architectures, ing in the change, few realize that the change is occur- and the growth of the Internet, have greatly expanded ring and even fewer know why it is happening. This the applicability of scripting languages. These trends article explains why scripting languages will handle will continue over the next decade, with more and many of the programming tasks in the next century more new applications written entirely in scripting better than system programming languages. languages and system programming -

Guide to Industry Classifications for International Surveys, 2012

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Bureau of Economic Analysis GUIDE TO INDUSTRY CLASSIFICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL SURVEYS, 2012 Industry classifications adapted from the 2012 North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) BE-799 (REV. 2-2012) Cover prints on Blue index, 110 sub INDUSTRY CLASSIFICATIONS The international surveys industry (ISI) classifications described here are to be used when completing the industry classifications items in BEA’s surveys of direct investment and services. The classifications and their code numbers were adapted by BEA from the 2012 North American Industry Classification System (hereafter referred to as the “2012 NAICS”). Industry classifications in the previous version of this guide were adapted from the 2007 North American Industry Classification System. Changes to ISI codes Reflecting the changes made to the NAICS for 2012, the new 2012 ISI classifications differ minimally from the 2007 ISI classifications. The table below summarizes the few reclassifications of activities that use a different ISI code from 2007: From: 2007 International Surveys To: 2012 International Surveys Industry Industry Activity that is reclassified Name Code Name Code MANUFACTURING Wood television, radio, and sewing Furniture and related 3370 Wood products manufacturing 3210 machine cabinet manufacturing products manufacturing (part) (part) Digital camera manufacturing Computer and peripheral 3341 Commercial and service industry 3333 equipment manufacturing (part) machinery manufacturing (part) WHOLESALE TRADE Gas household -

The Future of DNA Data Storage the Future of DNA Data Storage

The Future of DNA Data Storage The Future of DNA Data Storage September 2018 A POTOMAC INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES REPORT AC INST M IT O U T B T The Future O E P F O G S R IE of DNA P D O U Data LICY ST Storage September 2018 NOTICE: This report is a product of the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. The conclusions of this report are our own, and do not necessarily represent the views of our sponsors or participants. Many thanks to the Potomac Institute staff and experts who reviewed and provided comments on this report. © 2018 Potomac Institute for Policy Studies Cover image: Alex Taliesen POTOMAC INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES 901 North Stuart St., Suite 1200 | Arlington, VA 22203 | 703-525-0770 | www.potomacinstitute.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Findings 5 BACKGROUND 7 Data Storage Crisis 7 DNA as a Data Storage Medium 9 Advantages 10 History 11 CURRENT STATE OF DNA DATA STORAGE 13 Technology of DNA Data Storage 13 Writing Data to DNA 13 Reading Data from DNA 18 Key Players in DNA Data Storage 20 Academia 20 Research Consortium 21 Industry 21 Start-ups 21 Government 22 FORECAST OF DNA DATA STORAGE 23 DNA Synthesis Cost Forecast 23 Forecast for DNA Data Storage Tech Advancement 28 Increasing Data Storage Density in DNA 29 Advanced Coding Schemes 29 DNA Sequencing Methods 30 DNA Data Retrieval 31 CONCLUSIONS 32 ENDNOTES 33 Executive Summary The demand for digital data storage is currently has been developed to support applications in outpacing the world’s storage capabilities, and the life sciences industry and not for data storage the gap is widening as the amount of digital purposes. -

How Do You Know Your Search Algorithm and Code Are Correct?

Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Search (SoCS 2014) How Do You Know Your Search Algorithm and Code Are Correct? Richard E. Korf Computer Science Department University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095 [email protected] Abstract Is a Given Solution Correct? Algorithm design and implementation are notoriously The first question to ask of a search algorithm is whether the error-prone. As researchers, it is incumbent upon us to candidate solutions it returns are valid solutions. The algo- maximize the probability that our algorithms, their im- rithm should output each solution, and a separate program plementations, and the results we report are correct. In should check its correctness. For any problem in NP, check- this position paper, I argue that the main technique for ing candidate solutions can be done in polynomial time. doing this is confirmation of results from multiple in- dependent sources, and provide a number of concrete Is a Given Solution Optimal? suggestions for how to achieve this in the context of combinatorial search algorithms. Next we consider whether the solutions returned are opti- mal. In most cases, there are multiple very different algo- rithms that compute optimal solutions, starting with sim- Introduction and Overview ple brute-force algorithms, and progressing through increas- Combinatorial search results can be theoretical or experi- ingly complex and more efficient algorithms. Thus, one can mental. Theoretical results often consist of correctness, com- compare the solution costs returned by the different algo- pleteness, the quality of solutions returned, and asymptotic rithms, which should all be the same. -

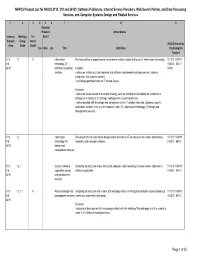

NAPCS Product List for NAICS 5112, 518 and 54151: Software

NAPCS Product List for NAICS 5112, 518 and 54151: Software Publishers, Internet Service Providers, Web Search Portals, and Data Processing Services, and Computer Systems Design and Related Services 1 2 3 456 7 8 9 National Product United States Industry Working Tri- Detail Subject Group lateral NAICS Industries Area Code Detail Can Méx US Title Definition Producing the Product 5112 1.1 X Information Providing advice or expert opinion on technical matters related to the use of information technology. 511210 518111 518 technology (IT) 518210 54151 54151 technical consulting Includes: 54161 services • advice on matters such as hardware and software requirements and procurement, systems integration, and systems security. • providing expert testimony on IT related issues. Excludes: • advice on issues related to business strategy, such as advising on developing an e-commerce strategy, is in product 2.3, Strategic management consulting services. • advice bundled with the design and development of an IT solution (web site, database, specific application, network, etc.) is in the products under 1.2, Information technology (IT) design and development services. 5112 1.2 Information Providing technical expertise to design and/or develop an IT solution such as custom applications, 511210 518111 518 technology (IT) networks, and computer systems. 518210 54151 54151 design and development services 5112 1.2.1 Custom software Designing the structure and/or writing the computer code necessary to create and/or implement a 511210 518111 518 application design software application. 518210 54151 54151 and development services 5112 1.2.1.1 X Web site design and Designing the structure and content of a web page and/or of writing the computer code necessary to 511210 518111 518 development services create and implement a web page. -

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary structures and semiotic square of oppositions Many systems of meaning are based on binary structures (masculine/ feminine; black/white; natural/artificial), two contrary conceptual categories that also entail or presuppose each other. Semiotic interpretation involves exposing the culturally arbitrary nature of this binary opposition and describing the deeper consequences of this structure throughout a culture. On the semiotic square and logical square of oppositions. Code A code is a learned rule for linking signs to their meanings. The term is used in various ways in media studies and semiotics. In communication studies, a message is often described as being "encoded" from the sender and then "decoded" by the receiver. The encoding process works on multiple levels. For semiotics, a code is the framework, a learned a shared conceptual connection at work in all uses of signs (language, visual). An easy example is seeing the kinds and levels of language use in anyone's language group. "English" is a convenient fiction for all the kinds of actual versions of the language. We have formal, edited, written English (which no one speaks), colloquial, everyday, regional English (regions in the US, UK, and around the world); social contexts for styles and specialized vocabularies (work, office, sports, home); ethnic group usage hybrids, and various kinds of slang (in-group, class-based, group-based, etc.). Moving among all these is called "code-switching." We know what they mean if we belong to the learned, rule-governed, shared-code group using one of these kinds and styles of language. -

Decoder-Tailored Polar Code Design Using the Genetic Algorithm

Decoder-tailored Polar Code Design Using the Genetic Algorithm Ahmed Elkelesh, Moustafa Ebada, Sebastian Cammerer and Stephan ten Brink Abstract—We propose a new framework for constructing a slight negligible performance degradation. The concatenation polar codes (i.e., selecting the frozen bit positions) for arbitrary with an additional high-rate Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC) channels, and tailored to a given decoding algorithm, rather than code [4] or parity-check (PC) code [6] further improves the based on the (not necessarily optimal) assumption of successive cancellation (SC) decoding. The proposed framework is based code performance itself, as it increases the minimum distance on the Genetic Algorithm (GenAlg), where populations (i.e., and, thus, improves the weight spectrum of the code. This collections) of information sets evolve successively via evolu- simple concatenation renders polar codes into a powerful tionary transformations based on their individual error-rate coding scheme. For short length codes [7], polar codes were performance. These populations converge towards an information recently selected by the 3GPP group as the channel codes for set that fits both the decoding behavior and the defined channel. Using our proposed algorithm over the additive white Gaussian the upcoming 5th generation mobile communication standard noise (AWGN) channel, we construct a polar code of length (5G) uplink/downlink control channel [8]. 2048 with code rate 0:5, without the CRC-aid, tailored to plain On the other hand, some drawbacks can be seen in their high successive cancellation list (SCL) decoding, achieving the same decoding complexity and large latency for long block lengths error-rate performance as the CRC-aided SCL decoding, and 6 under SCL decoding due to their inherent sequential decoding leading to a coding gain of 1dB at BER of 10− . -

U.S. Meatpacking: Dynamic Forces of Change in a Mature Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics 1st Quarter 2011 | 26(1) U.S. MEATPACKING: DYNAMIC FORCES OF CHANGE IN A MATURE INDUSTRY Brian L. Buhr and Bruce Ginn JEL Classifications: Q13, Q18, L11, L22, L2, L66 Keywords: Meatpacking, Five Forces, Competition, Supply Chain, Vertical Coordination, Relevant Markets Meatpacking in the United States is a mature industry. Overall domestic per capita meat consumption levels have been stable for the past 25 years. As typical of mature industries, meatpackers compete by reducing costs through technical change, increasing in size and scope through acquisition or vertical coordination and by expanding into developing international markets. Meatpackers have also gained subtle product differentiation and pricing advantages and modest brand loyalty by vertically coordinating genetics, feeding, and processing. This has resulted in improved ability to meet consumer demands; enhancing revenues rather than simply competing on costs. Although meatpacking is a mature industry, this is not to say that it does not face many dynamic forces of change. Entry into the U.S. market by foreign competitors has raised the global competitive ante. Environmental and social issues such as climate impacts on crops and water resources, the emergence of zoonotic diseases, and calls for improved animal welfare are changing management practices. Policy issues, including proposals to improve meat product safety, to reduce the use of antibiotics, and to place limits on animal ownership and contracting strategies, are also impacting packers. Our goal is to address the impact of these forces on meatpackers’ competitive strategies using Porter’s “Five Forces” analysis. -

Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts

BEHAVIOR ANALYST CERTIFICATION BOARD® = Professional and Ethical ® Compliance Code for = Behavior Analysts The Behavior Analyst Certification Board’s (BACB’s) Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (the “Code”) consolidates, updates, and replaces the BACB’s Professional Disciplinary and Ethical Standards and Guidelines for Responsible Conduct for Behavior Analysts. The Code includes 10 sections relevant to professional and ethical behavior of behavior analysts, along with a glossary of terms. Effective January 1, 2016, all BACB applicants and certificants will be required to adhere to the Code. _________________________ In the original version of the Guidelines for Professional Conduct for Behavior Analysts, the authors acknowledged ethics codes from the following organizations: American Anthropological Association, American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, American Sociological Association, California Association for Behavior Analysis, Florida Association for Behavior Analysis, National Association of Social Workers, National Association of School Psychologists, and Texas Association for Behavior Analysis. We acknowledge and thank these professional organizations that have provided substantial guidance and clear models from which the Code has evolved. Approved by the BACB’s Board of Directors on August 7, 2014. This document should be referenced as: Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Littleton, CO: Author. -

Industry Classification Benchmark (Equity) V3.8

Ground Rules Industry Classification Benchmark (Equity) v3.8 ftserussell.com An LSEG Business June 2021 Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................................................... 4 1.1 Industry Classification Benchmark .................................................... 4 1.2 FTSE Russell .................................................................................... 4 2.0 Management Responsibilities ....................................... 5 2.1 FTSE Russell .................................................................................... 5 2.2 FTSE Russell Industry Classification Advisory Committee ........ 5 2.3 FTSE Russell Policy Advisory Board ............................................ 5 3.0 FTSE Russell Index Policies ......................................... 6 3.1 Challenges and Appeals ................................................................. 6 3.2 Policy for Benchmark Methodology Changes ................................... 6 4.0 Classification Guidelines .............................................. 7 4.1 Basis of Decisions ........................................................................... 7 4.2 Allocation of Companies to Subsectors ....................................... 7 4.3 Changes to the Classification of a Company ............................... 8 4.4 Industry Sectors .............................................................................. 8 4.5 Changes to the Industry Classification Benchmark .................... 9 5.0 Periodic Reviews ........................................................