A Country Boy… 1928 – 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meppershall at Christmas

Volume 3435 DecemberOctober 2019/January 2018 2020 Issue 68 Meppershall Village Website: www.meppershall.org 1 Contents Editorial by Mick Ridley and James Read .............................................. 2 Letters to the Editors .............................................................................. 3 Aerial Combat By Susanne Wright ..................................................... 4 Meppershall at Christmas ....................................................................... 5 Garden Waste Collections – Important Dates ......................................... 6 Walnut Tree Café .................................................................................... 6 Meppershall Speed Watch – Results ....................................................... 7 Meppershall Living Advent Calendar....................................................... 8 While away winter with a good book and much more…… .................... 10 Family Christmas Sing-Along ................................................................. 11 Parish Church of St Mary The Virgin (Church of England) ...................... 12 Church Services and Events – December 2019 ...................................... 14 Church Services and Events – January 2020 .......................................... 15 Meppershall Pre-School ........................................................................ 16 Meppershall Brownies .......................................................................... 17 Browzers are Wowzing Meppershall! .................................................. -

Area D Assessments

Central Bedfordshire Council www.centralbedfordshire.gov.uk Appendix D: Area D Assessments Central Bedfordshire Council Local Plan Initial Settlements Capacity Study CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COUNCIL LOCAL PLAN: INITIAL SETTLEMENTS CAPACITY STUDY Appendix IID: Area D Initial Settlement Capacity Assessment Contents Table BLUNHAM .................................................................................................................. 1 CAMPTON ................................................................................................................. 6 CLIFTON ................................................................................................................... 10 CLOPHILL ................................................................................................................. 15 EVERTON .................................................................................................................. 20 FLITTON & GREENFIELD ............................................................................................ 24 UPPER GRAVENHURST ............................................................................................. 29 HAYNES ................................................................................................................... 33 LOWER STONDON ................................................................................................... 38 MAULDEN ................................................................................................................ 42 MEPPERSHALL ......................................................................................................... -

Thomas Parrott of Shillington

by Margaret Lewis (1177) in association with Wayne Parrott (775) and Harald Reksten (522) Born around th e time of the English Reformation, during the reign of Henry VIII, Tho mas Parrat of Shillington, Bedfordshire, was to live through th e turbulent times of th e succession of Henry's children, and then th e golden age of Elizabethan England. Al th ough spending most of his life in Shillin gton, Thomas was probably born in Luton, around 1535, based on the marriage date of his eldest son (1574). It has been sug gested that he is one of the sons of Thomas & Agnes Parret of Luton. This Thomas signed his will in 1558 at which time his son Thomas was aged less than 21 years, so it is a possibility. Whatever his origin, Thomas was obviously a man of means, and is frequently re ferred to as gentJeman in documents, as were his sons. H e managed to acquire quite a range of property during his lifetime. As well as holding property in Luton, S hilling ton and Upper Stondon in Bedfordshire, he also had land and farms in the parishes of Old Weston, Brington, By thorn, and Leighton Bromswold in Huntingdonshire. It is believed that he was the builder of the present day Model Farm in Old Weston. Thomas married some time before 1570 when he first appears in the Shillington regis ter. Based on his will he had four children before this time - namely Thomas (who married 1574), Robert (married by 1592), Mary (married in 1590) and Abraham (also married in 1590). -

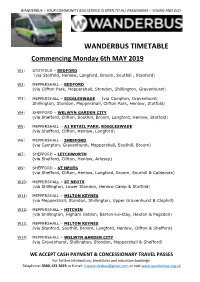

WANDERBUS TIMETABLE Commencing Monday 6Th MAY 2019

WANDERBUS – YOUR COMMUNITY BUS SERVICE IS OPEN TO ALL PASSENGERS – YOUNG AND OLD WANDERBUS TIMETABLE Commencing Monday 6th MAY 2019 W1: STOTFOLD – BEDFORD (via Stotfold, Henlow, Langford, Broom, Southill , Stanford) W2: MEPPERSHALL – BEDFORD (via Clifton Park, Meppershall, Stondon, Shillington, Gravenhurst) W3: MEPPERSHALL – BIGGLESWADE (via Campton, Gravenhurst, Shillington, Stondon, Meppershall, Clifton Park, Henlow, Stotfold) W4: SHEFFORD – WELWYN GARDEN CITY (via Shefford, Clifton, Southill, Broom, Langford, Henlow, Stotfold) W5: MEPPERSHALL – A1 RETAIL PARK, BIGGLESWADE (via Shefford, Clifton, Henlow, Langford) W6: MEPPERSHALL – SHEFFORD (via Campton, Gravenhurst, Meppershall, Southill, Broom) W7: SHEFFORD – LETCHWORTH (via Shefford, Clifton, Henlow, Arlesey) W9: SHEFFORD – ST NEOTS (via Shefford, Clifton, Henlow, Langford, Broom, Southill & Caldecote) W10: MEPPERSHALL – ST NEOTS (via Shillington, Lower Stondon, Henlow Camp & Stotfold) W11: MEPPERSHALL – MILTON KEYNES (via Meppershall, Stondon, Shillington, Upper Gravenhurst & Clophill) W12: MEPPERSHALL – HITCHIN (via Shillington, Higham Gobion, Barton-Le-Clay, Hexton & Pegsdon) W13: MEPPERSHALL – MILTON KEYNES (via Stanford, Southill, Broom, Langford, Henlow, Clifton & Shefford) W14: MEPPERSHALL – WELWYN GARDEN CITY (via Gravenhurst, Shillington, Stondon, Meppershall & Shefford) WE ACCEPT CASH PAYMENT & CONCESSIONARY TRAVEL PASSES For further information, timetables and excursion bookings: Telephone: 0300-123-3023 or E-mail: [email protected] or visit www.wanderbus.org.uk WANDERBUS -

Kelly's Trade Directory Biggleswade - 1898

Home Kelly's Trade Directory Biggleswade - 1898 I have transcribed the directory exactly as written, complete with abbreviations and punctuation that seem rather peculiar to us now. BIGGLESWADE is a market and union town, head of a petty sessional division and county court district, with a station on the Great Northern railway, 45 miles from London by the high road and 41 by rail 10½ south-east from Bedford and 11 north from Hitchin, in the Northern division of the county, hundred and rural deanery of Biggleswade, archdeaconry of Bedford and diocese of Ely, bordered on the west by the river Ivel, formerly navigable from its junction with the Ouse at Tempsford, about 4 miles distant, but in pursuance of the "Ivel Navigation Act" of 1876, the locks have been allowed to fall into disuse. The town was formerly governed by a Local Board, created by an Order of the Bedfordshire County Council, February, 22, 1892 but under the previous of the "Local Government Act, 1894" (56 & 57 Vict. ch. 73), it is now under control of an Urban District Council of 12 members; it is well lighted with gas supplied by a company, and water is obtained from springs in the neighbourhood. The church of St Andrew is an edifice of sandstone, in the Perpendicular style, consisting of chancel, clerestoried nave of four bays, aisles, south porch and an embattled western tower, rebuilt in 1720, and containing a clock and 5 bells : the chancel. rebuilt in 1467, by John Ruding, retains its piscina and sedilia for three priests, but the former has no basin and is now used as a credence table; a beautiful alter-piece, representing the "Last Supper", was presented by Charles Barnett esq. -

Review Ofupper Stondon Information.Pdf

Review of - 170531_area_d_assessments Upper Stondon We have found a number of significant errors in the report. It separates Upper and Lower Stondon and lack clarity on where the break of the two areas is. The break between the two is a green area. Upper Stondon has at most 3 houses and the Church along with two small commercial areas. It is not good to separate the two areas of the same Village! Stated Stondon is a village in the east of Central Bedfordshire and has a population of 2,300 people and contains 1,110 dwellings (population and dwellings combine Upper and Lower Stondon)350. The settlement is around 10 miles east of Flitwick and around 7 miles south of Biggleswade. Stondon is divided into two sections, Upper Stondon and Lower Stondon, with Lower Stondon being the larger of the two villages. Correction Why are Upper and Lower Stondon looked at separately? There is no real separation. The number of dwellings is 1023 based on last precept. Stated. Upper Stondon does not contain any services and facilities. Upper Stondon has 1 small Leisure Strategy site, whilst Stondon as a whole has a surplus of formal large recreation areas, play areas for children and facilities for young people. However, there is a deficit of informal large recreation areas, small amenity spaces and allotments. Correction This seems to contradict the information provided for Lower Stondon. There is no small Leisure Strategy site in Upper Stondon. Stondon as a whole has allotments and a range of spaces. http://www.centralbedfordshire.gov.uk/Images/stondon-leisure-schedule_tcm3-22084.pdf Stated However, there is a deficit of informal large recreation areas, small amenity spaces and allotments Correction There are:- Two large recreation areas (Hillside Road, Pollards Way) Allotments (since 2012 and 60 plots) What are amenity spaces? A large number of play areas. -

6 the Pastures, Upper Stondon, SG16 6QB Guide Price £599,950

6 The Pastures, Upper Stondon, SG16 6QB Guide price £599,950 6 The Pastures, Upper Stondon, SG16 6QB The Pastures is a small development of just six substantial detached houses, constructed to an excellent specification by Potton Homes. Situated on the edge of the village the house backs directly on to the recreation ground. Nearby Lower Stondon has shops for day to day needs, a public house, bus stops and access to the A1(M) via the A507. Hitchin, some 5 miles to the south accessed via the A600, provides a comprehensive range of shopping and recreational facilities together with excellent schooling and a mainline station. The closest train station is at Arlesey (about 3 miles). The well presented accommodation, which has much of the timber frame exposed, has gas central heating and double glazing. GROUND FLOOR ENTRANCE PORCH Exterior light. Front door to: ENTRANCE HALL Timber floor. Exposed timbers. Wall light point. Staircase to first floor with cupboard under. CLOAKROOM Double glazed window to front. Low level wc and pedestal wash hand basin. Tiled splash back. Radiator. Tiled floor. SITTING ROOM 22'7 x 13'10 (6.88m x 4.22m) Double glazed window to front. Double glazed window and casement doors to rear. Two radiators. Feature brick inglenook style fireplace with gas stove. DINING ROOM 14'10 x 9' (4.52m x 2.74m) Double glazed windows to front and side. Radiator. Exposed timbers. LIVING ROOM 20'8 x 15' (6.30m x 4.57m) Double glazed casement doors and window to side. Double glazed bay window to rear. -

Mid Beds Green Infrastructure Plan Process

Contents Foreword 4 Acknowledgements 5 Executive Summary 6 1.0 Introduction 10 1.1 Need for the Plan 10 1.2 Policy Background 11 1.3 What is Green Infrastructure? 12 1.4 Aim & Objectives 13 2.0 Context 14 2.1 Environmental context 14 2.2 Growth context 15 3.0 The Plan Preparation Process 18 3.1 Baseline Review 18 3.2 Stakeholder & Community Consultation 19 3.3 Integration Process 20 3.4 The Green Infrastructure Network 20 3.5 Project Lists 21 4.0 Network Area Descriptions and Project List 24 4.1 Forest of Marston Vale 24 4.2 The Ivel Valley 29 4.3 The Greensand Ridge 33 4.4 The Flit Valley 34 4.5 The Southern Clay Ridge and Vale 35 4.6 The Chilterns 36 5.0 Implementation 38 5.1 Introduction 38 5.2 Project Prioritisation 38 5.3 Delivering through the Planning System 38 5.4 Agriculture & Forestry 40 5.5 Local Communities 40 5.6 Partner Organisations 40 5.7 Funding 41 5.8 Monitoring & Review 41 6.0 Landscape 43 7.0 Historic Environment 57 8.0 Biodiversity 64 9.0 Accessible Greenspace 77 10.0 Access Routes 86 Appendices 96 1 Bedfordshire and Luton Green Infrastructure Consortium Members 97 2 Existing GI Assets on Base Maps 98 3 Themes Leaders 99 4 Workshop Results and Attendees 100 5 Potential Criteria for Prioritising GI Projects 126 6 Landscape 128 Appendix 6a – Table of Valued Landmarks, Views and Sites Appendix 6b – Condition of Landscape Character Areas 7 Historic Environment 131 Appendix 7a Historic Environment Character Areas in Mid Bedfordshire 8 Accessible Greenspace 140 8a. -

VILLAGER Issue 87 - February 2016 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS

The VILLAGER Issue 87 - February 2016 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS Inside this issue Fairtrade Fortnight Portugal Cruising on the Douro River Win £25 in our Prize Crossword Bringing Local Business to Local People in Langford, Henlow, Shefford, Stanford, Hinxworth, Ickleford, Caldecote, Radwell, Shillington, Pirton, Upper and Lower Stondon, Gravenhurst, Holwell, Meppershall, Baldock, Stotfold, Arlesey, Hitchin & Letchworth Your FREEcopy 2 Please mention The Villager and Town Life when responding to adverts e VILLAGER Issue 87 - February 2016 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS Inside this issue Fairtrade Fortnight Portugal Cruising on the Douro River Win £25 in our Prize Crossword Bringing Local Business to Local People in Langford, Henlow, Shefford, Stanford, Hinxworth, Ickleford, Caldecote, Radwell, Shillington, Pirton, Upper and Lower Stondon, Gravenhurst, Holwell, Meppershall, Baldock, Stotfold, Arlesey, Hitchin & Letchworth Your Contents FREEcopy Beer at Home ..........................................................................36 Chinese New Year Animal Heroes .........................................................................39 28 Fiat 500 ...................................................................................41 Golden Years ...........................................................................43 Seasonal Delights ....................................................................44 -

Parish Profile

The Benefice of Shillington, Gravenhurst and Stondon PARISH PROFILE April 2012 Page 1 Our mission is to provide a welcoming place of worship where, with open minds, we can live God’s love together within a supportive and listening community. Page 2 THE BENEFICE OF SHILLINGTON, GRAVENHURST AND STONDON PARISH PROFILE Contents The villages of Shillington, Gravenhurst and Stondon 4 The churches 6 Church Services 8 Congregation and activities 10 Publicity and finances 12 Our vision for the future 13 The new incumbent 14 Church Support and local links 15 Click on the map to see where we are Page 3 THE VILLAGES Shillington and Gravenhurst Many local activities and groups thrive including, Toddlers, Playgroup, Cubs, Brownies, Guides, Scouts, WI and a Lunch Club run by the Congregational Church. Apart from agriculture, local enterprises in the form of plant nurseries, kennels/cattery and small service industries have developed within the community. Gravenhurst is a smaller settlement of some 500 souls, set on a hill over the valley to the north and just less than two miles distant by road. It is another picturesque Set in rural Bedfordshire and surrounded by village and it and Shillington are blessed with hills and open farmland, Shillington is a as fine a network of footpaths and charming village with a population of some bridleways as one could find anywhere. Its 2000 inhabitants. own church, St. Giles, was declared Shillington originally comprised a number of redundant in 2007 and the former Parish of hamlets or “Ends” with tracks connecting Upper with Lower Gravenhurst was merged them. -

VILLAGER Issue 96 - November 2016 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS

The VILLAGER Issue 96 - November 2016 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS In this issue Win a YippeeYo Firework Fiestas! Win £25 in our Prize Crossword Bringing Local Business to Local People in Langford, Henlow, Shefford, Stanford, Hinxworth, Ickleford, Caldecote, Radwell, Fairfield Park, Shillington, Pirton, Upper and Lower Stondon, Gravenhurst, Holwell, Meppershall, Baldock, Stotfold, Arlesey, Hitchin & Letchworth Your FREEcopy RELAX 2_Layout 1 12/02/2015 07:51 Page 1 Relax & Renew B e a u t y S t u d i o Voted Americas most wanted non-invasive beauty treatment Suitable for all skin types, the Venus Freeze is a comfortable warm treatment that's used as a non-surgical face lift, helping to improve lines, wrinkles, jowls & a double chin. On the body it will tighten loose skin, reduce cellulite & fat, resulting in a more defined youthful appearance. What results will I get? Tighter skin • Softening of wrinkles • More youthful appearance • Reduced cellulite • More contoured silhouette • All this with... NO downtime • NO pain • NO Discomfort • Just £25 for a taster session when you mention the Villager Call today for a free consultation www.renewbeautystudio.co.uk [email protected] 2T: 07984 744 218 Please M mentionillard The W Villageray, H anditc Townhin Life, H whenert respondings SG4 0 toQ advertsE The VILLAGER Issue 95 - October 2016 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS In this issue Win tickets to an evening of -

VILLAGER Issue 101 - April 2017 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS

The VILLAGER Issue 101 - April 2017 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS In this issue Win Tickets to see The Saw Doctors Who do you think we are? Win £25 in our Prize Crossword Bringing Local Business to Local People in Langford, Henlow, Shefford, Stanford, Hinxworth, Ickleford, Caldecote, Radwell, Fairfield Park, Shillington, Pirton, Upper and Lower Stondon, Gravenhurst, Holwell, Meppershall, Baldock, Stotfold, Arlesey, Hitchin & Letchworth Your FREEcopy The Old White Horse • 1 High Street • Biggleswade • SG18 0JE Tel: 01767 314344 www.lolineinteriors.co.uk e: [email protected] 2 Please mention The Villager and Town Life when responding to adverts The VILLAGER Issue 101 - April 2017 and Town Life LOCAL NEWS • LOCAL PEOPLE • LOCAL SERVICES • LOCAL CHARITIES • LOCAL PRODUCTS In this issue Win Tickets to see The Saw Doctors Who do you think we are? Win £25 in our Prize Crossword Bringing Local Business to Local People in Langford, Henlow, Shefford, Stanford, Hinxworth, Ickleford, Caldecote, Radwell, Fairfield Park, Shillington, Pirton, Upper and Lower Stondon, Gravenhurst, Holwell, Meppershall, Baldock, Stotfold, Arlesey, Hitchin & Letchworth Your Contents FREEcopy A M Optometrists ....................................................................40 The Garage Shefford Ltd Fuchsia Perfect ........................................................................42 Flower Power ..........................................................................45 John Bunyan Boat ...................................................................48