LIVIA BEFORE OCTAVIAN* However, Following the Lead of Tactius And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

Resettlement Into Roman Territory Across the Rhine and the Danube Under the Early Empire (To the Marcomannic Wars)*

Eos C 2013 / fasciculus extra ordinem editus electronicus ISSN 0012-7825 RESETTLEMENT INTO ROMAN TERRITORY ACROSS THE RHINE AND THE DANUBE UNDER THE EARLY EMPIRE (TO THE MARCOMANNIC WARS)* By LESZEK MROZEWICZ The purpose of this paper is to investigate the resettling of tribes from across the Rhine and the Danube onto their Roman side as part of the Roman limes policy, an important factor making the frontier easier to defend and one way of treating the population settled in the vicinity of the Empire’s borders. The temporal framework set in the title follows from both the state of preser- vation of sources attesting resettling operations as regards the first two hundred years of the Empire, the turn of the eras and the time of the Marcomannic Wars, and from the stark difference in the nature of those resettlements between the times of the Julio-Claudian emperors on the one hand, and of Marcus Aurelius on the other. Such, too, is the thesis of the article: that the resettlements of the period of the Marcomannic Wars were a sign heralding the resettlements that would come in late antiquity1, forced by peoples pressing against the river line, and eventu- ally taking place completely out of Rome’s control. Under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, on the other hand, the Romans were in total control of the situation and transferring whole tribes into the territory of the Empire was symptomatic of their active border policies. There is one more reason to list, compare and analyse Roman resettlement operations: for the early Empire period, the literature on the subject is very much dominated by studies into individual tribe transfers, and works whose range en- * Originally published in Polish in “Eos” LXXV 1987, fasc. -

Vestal Virgins and Their Families

Vestal Virgins and Their Families Andrew B. Gallia* I. INTRODUCTION There is perhaps no more shining example of the extent to which the field of Roman studies has been enriched by a renewed engagement with anthropology and other cognate disciplines than the efflorescence of interest in the Vestal virgins that has followed Mary Beard’s path-breaking article regarding these priestesses’ “sexual status.”1 No longer content to treat the privileges and ritual obligations of this priesthood as the vestiges of some original position (whether as wives or daughters) in the household of the early Roman kings, scholars now interrogate these features as part of the broader frameworks of social and cultural meaning through which Roman concepts of family, * Published in Classical Antiquity 34.1 (2015). Early versions of this article were inflicted upon audiences in Berkeley and Minneapolis. I wish to thank the participants of those colloquia for helpful and judicious feedback, especially Ruth Karras, Darcy Krasne, Carlos Noreña, J. B. Shank, and Barbara Welke. I am also indebted to George Sheets, who read a penultimate draft, and to Alain Gowing and the anonymous readers for CA, who prompted additional improvements. None of the above should be held accountable for the views expressed or any errors that remain. 1 Beard 1980, cited approvingly by, e.g., Hopkins 1983: 18, Hallett 1984: x, Brown 1988: 8, Schultz 2012: 122. Critiques: Gardner 1986: 24-25, Beard 1995. 1 gender, and religion were produced.2 This shift, from a quasi-diachronic perspective, which seeks explanations for recorded phenomena in the conditions of an imagined past, to a more synchronic approach, in which contemporary contexts are emphasized, represents a welcome methodological advance. -

Brutus, Cassius, Judas, and Cremutius Cordus: How

BRUTUS, CASSIUS, JUDAS, AND CREMUTIUS CORDUS: HOW SHIFTING PRECEDENTS ALLOWED THE LEX MAIESTATIS TO GROUP WRITERS WITH TRAITORS by Hunter Myers A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, Mississippi May 2018 Approved by ______________________________ Advisor: Professor Molly Pasco-Pranger ______________________________ Reader: Professor John Lobur ______________________________ Reader: Professor Steven Skultety © 2018 Hunter Ross Myers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Pasco-Pranger, For your wise advice and helpful guidance through the thesis process Dr. Lobur & Dr. Skultety, For your time reading my work My parents, Robin Myers and Tracy Myers For your calm nature and encouragement Sally-McDonnell Barksdale Honors College For an incredible undergraduate academic experience iii ABSTRACT In either 103 or 100 B.C., a concept known as Maiestas minuta populi Romani (diminution of the majesty of the Roman people) is invented by Saturninus to accompany charges of perduellio (treason). Just over a century later, this same law is used by Tiberius to criminalize behavior and speech that he found disrespectful. This thesis offers an answer to the question as to how the maiestas law evolved during the late republic and early empire to present the threat that it did to Tiberius’ political enemies. First, the application of Roman precedent in regards to judicial decisions will be examined, as it plays a guiding role in the transformation of the law. Next, I will discuss how the law was invented in the late republic, and increasingly used for autocratic purposes. The bulk of the thesis will focus on maiestas proceedings in Tacitus’ Annales, in which a total of ten men lose their lives. -

“At the Sight of the City Utterly Perishing Amidst the Flames Scipio Burst Into

Aurelii are one of the three major Human subgroups within western Eramus, and the founders of the mighty (some say “Eternal”) “At the sight of the city utterly perishing Aurelian Empire. They are a sturdy, amidst the flames Scipio burst into tears, conservative group, prone to religious fervor and stood long reflecting on the inevitable and philosophical revelry in equal measure. change which awaits cities, nations, and Adding to this a taste for conquest, and is it dynasties, one and all, as it does every one any wonder the Aurelii spread their of us men. This, he thought, had befallen influence, like a mighty eagle spreading its Ilium, once a powerful city, and the once wings, across the known world? mighty empires of the Assyrians, Medes, Persians, and that of Macedonia lately so splendid. And unintentionally or purposely he quoted---the words perhaps escaping him Aurelii stand a head shorter than most unconsciously--- other humans, but their tightly packed "The day shall be when holy Troy shall forms hold enough muscle for a man twice fall their height. Their physical endurance is And Priam, lord of spears, and Priam's legendary amongst human and elf alike. folk." Only the Brutum are said to be hardier, And on my asking him boldly (for I had and even then most would place money on been his tutor) what he meant by these the immovable Aurelian. words, he did not name Rome distinctly, but Skin color among the Aurelii is quite was evidently fearing for her, from this sight fluid, running from pale to various shades of the mutability of human affairs. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Handout Name Yourself Like a Roman (CLAS 160)

NAME YOURSELF LIKE A ROMAN Choose Your Gender 0 Roman naming conventions differed for men and women, and the Romans didn’t conceive of other options or categories (at least for naming purposes!). For viri (men): Choose Your Praenomen (“first name”) 1 This is your personal name, just like modern American first names: Michael, Jonathan, Jason, etc. The Romans used a very limited number of first names and tended to be very conservative about them, reusing the same small number of names within families. In the Roman Republic, your major options are: Some of these names (Quintus, Sextus, • Appius • Manius • Servius Septimus, etc.) clearly originally referred • Aulus • Marcus • Sextus to birth order: Fifth, Sixth, Seventh. Others are related to important aspects of • Decimus • Numerius • Spurius Roman culture: the name Marcus probably • Gaius • Postumus • Statius comes from the god Mars and Tiberius from the river Tiber. Other are mysterious. • Gnaeus • Publius • Tiberius But over time, these names lost their • Lucius • Quintus • Titus original significance and became hereditary, with sons named after their • Mamercus • Septimus • Vibius father or another male relative. Choose Your Nomen (“family name”) 2 Your second name identifies you by gens: family or clan, much like our modern American last name. While praenomina vary between members of the same family, the nomen is consistent. Some famous nomina include Claudius, Cornelius, Fabius, Flavius, Julius, Junius, and Valerius. Side note: if an enslaved person was freed or a foreigner was granted citizenship, they were technically adopted into the family of their “patron,” and so received his nomen as well. De Boer 2020 OPTIONAL: Choose Your Cognomen (“nickname”) Many Romans had just a praenomen and a nomen, and it was customary and polite to address a 3 person by this combo (as in “hello, Marcus Tullius, how are you today?” “I am well, Gaius Julius, and you?”). -

Dear Graduates, Nova Southeastern University Takes

Dear Graduates, Nova Southeastern University takes enormous pride in your success. On behalf of NSU’s faculty, staff, and Board of Trustees, I salute your academic and personal achievement. You have reached this milestone through hard work and intellectual effort, and we are pleased to recognize your dedication with today’s commencement ceremony. Reflect on the gifts of knowledge and support you have received. Celebrate the friendships, skills, and strengths you have forged. Embrace the opportunity to apply these treasures as you start a new chapter in your life, hopefully, following your passion, not your fortune. Our best wishes are with you today and in the future. Congratulations! George L. Hanbury II, Ph.D. NSU President and CEO CEREMONY SCHEDULE May 16, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. Shepard Broad College of Law May 17, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. All Undergraduate Degrees May 17, 2021, at 3:00 p.m. H. Wayne Huizenga College of Business and Entrepreneurship May 18, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. College of Dental Medicine Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine College of Psychology May 18, 2021, at 3:00 p.m. College of Optometry College of Pharmacy Ron and Kathy Assaf College of Nursing May 19, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. Abraham S. Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice Halmos College of Arts and Sciences College of Computing and Engineering May 19, 2021, at 3:00 p.m. Dr. Pallavi Patel College of Health Care Sciences 2 CLASS OF 2021 THE ACADEMIC PROCESSION Grand Marshal Degree Candidates Members of the Faculty Members of the Board of Trustees Distinguished Guests University Officials 3 WELCOME TO THE 2021 COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES for NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY May 16 to 19, 2021 4 CLASS OF 2021 ORDER OF EXERCISES SHEPARD BROAD COLLEGE OF LAW MAY 16, 2021, AT 9:30 A.M. -

Women in Livy and Tacitus

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2021-5 Women in Livy and Tacitus STEPHEN ALEXANDER PREVOZNIK Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation PREVOZNIK, STEPHEN ALEXANDER, "Women in Livy and Tacitus" (2021). Honors Bachelor of Arts. 46. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/46 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women in Livy and Tacitus By Stephen Prevoznik Prevoznik 1 Introduction Livy and Tacitus are both influential and important Roman authors. They have written two of the most influential histories of Rome. Livy covers from the founding of Rome until the Reign of Augustus. Tacitus focuses on the early empire, writing from the end of Augustus’ reign through Nero. This sets up a nice symmetry, as Tacitus picks up where Livy stops. Much has been written about the men they include, but the women also play an important role. This essay plans to outline how the women in each work are used by the authors to attain their goals. In doing so, each author’s aim is exposed. Livy: Women as Exempla Livy’s most famous work, Ab Urbe Condita, is meant to be read as a guide. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Archaeological and Literary Etruscans: Constructions of Etruscan Identity in the First Century Bce

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND LITERARY ETRUSCANS: CONSTRUCTIONS OF ETRUSCAN IDENTITY IN THE FIRST CENTURY BCE John B. Beeby A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: James B. Rives Jennifer Gates-Foster Luca Grillo Carrie Murray James O’Hara © 2019 John B. Beeby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT John B. Beeby: Archaeological and Literary Etruscans: Constructions of Etruscan Identity in the First Century BCE (Under the direction of James B. Rives) This dissertation examines the construction and negotiation of Etruscan ethnic identity in the first century BCE using both archaeological and literary evidence. Earlier scholars maintained that the first century BCE witnessed the final decline of Etruscan civilization, the demise of their language, the end of Etruscan history, and the disappearance of true Etruscan identity. They saw these changes as the result of Romanization, a one-sided and therefore simple process. This dissertation shows that the changes occurring in Etruria during the first century BCE were instead complex and non-linear. Detailed analyses of both literary and archaeological evidence for Etruscans in the first century BCE show that there was a lively, ongoing discourse between and among Etruscans and non-Etruscans about the place of Etruscans in ancient society. My method musters evidence from Late Etruscan family tombs of Perugia, Vergil’s Aeneid, and Books 1-5 of Livy’s history. Chapter 1 introduces the topic of ethnicity in general and as it relates specifically to the study of material remains and literary criticism. -

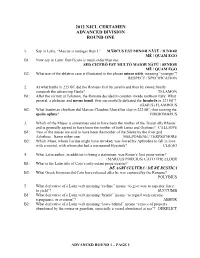

2012 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Say in Latin, “Marcus is younger than I.” MĀRCUS EST MINOR NĀTŪ / IUNIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B1: Now say in Latin: But Cicero is much older than me. SED CICERŌ EST MULTŌ MAIOR NĀTŪ / SENIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B2: What use of the ablative case is illustrated in the phrase minor nātū, meaning “younger”? RESPECT / SPECIFICATION 2. At what battle in 225 BC did the Romans first by javelin and then by sword finally vanquish the advancing Gauls? TELAMON B1: After the victory at Telamon, the Romans decided to counter-invade northern Italy. What general, a plebeian and novus homō, first successfully defeated the Insubrēs in 223 BC? (GAIUS) FLAMINIUS B2: What Insubrian chieftain did Marcus Claudius Marcellus slay in 222 BC, thus earning the spolia opīma? VIRIDOMARUS 3. Which of the Muses is sometimes said to have been the mother of the Trojan ally Rhesus and is generally agreed to have been the mother of both Linus and Orpheus? CALLIOPE B1: Two of the muses are said to have been the mother of the Sirens by the river god Achelous. Name either one. MELPOMENE / TERPSICHORE B2: Which Muse, whom Tacitus might have invoked, was forced by Aphrodite to fall in love with a mortal, with whom she had a son named Hyacinth? CL(E)IO 4. What Latin author, in addition to being a statesman, was Rome’s first prose writer? (MARCUS PORCIUS) CATO THE ELDER B1: What is the Latin title of Cato’s only extant prose treatise? DĒ AGRĪ CULTŪRĀ / DĒ RĒ RUSTICĀ B2: What Greek historian did Cato have released after he was captured by the Romans? POLYBIUS 5.