Cornelia Connelly)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornelia Connelly, SHCJ

Table of Contents Cornelia Connelly, SHCJ (1809-1879) 4 The Early Years 8 Converting to Catholicism 10 Agonizing Losses 12 The Ultimate Sacrifice 14 Meeting the “Wants of the Age” 16 Transitions & Compromises 18 The Society’s Roots 20 St. Leonards-on-Sea 22 Testing the Limits 24 Struggles & Scandals 26 A Flourishing Community 28 2 Cornelia Connelly, SHCJ (1809-1879) “I hope always to be able to do something for His glory, be it only in not resisting His grace.” • Cornelia Connelly The life of Cornelia Connelly was anything but typical. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on January 15, 1809, Cornelia defined the norms of her time. She became a wife, mother to five children, Catholic nun, and ultimately, the Foundress of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, an order of Roman Catholic Sisters. Cornelia’s spirit of infinite love, compassionate zeal, and steadfast faith continues to influence the work that the Sisters of the Holy Child do today. During this year of celebration marking the 200th Anniversary of Cornelia’s birth, we gather to honor her, as well as to celebrate her legacy and the service that changes the lives of people around the world. Learn more about Cornelia. Table of Contents 4 “Since graduating from Rosemont College, I’ve grown to appreciate Cornelia’s life story even more. Her faith and mission were profound, especially in the midst Cornelia lived during the 1800s, and as Sr. Radegune Flaxman of great personal struggle.” writes in her book, A Woman Styled Bold, “In an age when women were regarded as men’s property, when society and the Church —Pat Ciarrocchi, Rosemont College Alum ’74 expected them to be unquestioningly obedient and submissive, Cornelia struggled to retain her integrity and to be true to her God. -

Cornelia in Rome Lancaster.Pdf

CORNELIA AND ROME BEFORE WE BEGIN… •PLEASE KEEP IN MIND THAT •It is over 170 years since Cornelia first came to Rome •The Rome Cornelia visited was very different from the one that you are going to get to know whilst you are here •But you will be able to see and visit many places Cornelia knew and which she would still recognise WHAT WE ARE GOING TO DO •Learn a little bit about what Rome was like in the nineteenth century when Cornelia came •Look at the four visits Cornelia made to Rome in 1836-37, 1843-46, 1854, 1869 •Find out what was happening in Cornelia’s life during each visit ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY •It was a very small city with walls round it •You could walk right across it in two hours •Most houses were down by the river Tiber on the opposite bank from the Vatican •Inside the walls, as well as houses, there were vineyards and gardens, and many ruins from ancient Rome ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY •Some inhabitants (including some clergy) were very rich indeed, but the majority of people were very, very poor •The streets were narrow and cobbled and had no lighting, making them exremely dangerous once it went dark •The river Tiber often flooded the houses on its banks •Cholera epidemics were frequent ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY • You can see how overcrowded the city was when Cornelia knew it • There were magnificent palaces and church buildings but most people lived in wretchedly poor conditions • Injustice, violence and crime were part of everyday life ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY • The river Tiber flowed right up against the houses • It -

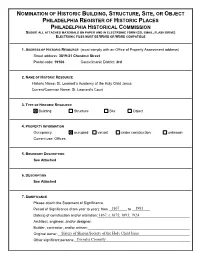

Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address: 3819-31 Chestnut Street Postal code: 19106 Councilmanic District: 3rd 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name: St. Leonard’s Academy of the Holy Child Jesus Current/Common Name: St. Leonard’s Court 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use: Offices 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See Attached 6. DESCRIPTION See Attached 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1867 to _________1981 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_1867;____________________________________ c.1875; 1893; 1924 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________ _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________ _________________________ Original owner:_________________________________________________________Sisters of Sharon/Society of the Holy Child Jesus _________ Other significant persons:_________________________________________________Cornelia Connelly _________ CRITERIA FOR DESIGNATION: The historic resource satisfies the following criteria for designation -

Archbishop Ryan Correspondence

Most Reverend James Wood Correspondence 52.542M To Reverend Clergy, from Pope Pius IX, 11/20/1846, Bull of 1846 on declaration of powers of the clergy 51.698Ro From Pope Pius IX, two handwritten excerpts from the Decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Pius IX (01/25/1848) (Latin) 51.179Acl 10/27/1848, Document of Reverend C. McDermott’s citizenship 53.938 1849, Pastoral Letter of Archbishop Wood 50.01 Instruction Book I (1845 – 46), a. Instruction 1, the Church of the Living God – summary on the Church; b. Instruction 2, the Church of Christ is Visible 50.02 Instruction Book II (1845 – 46), a. Instruction 3, Protestants acknowledge a visible Church and they are not that church; b. Instruction 4, Protestants and the visible church 50.03 Instruction Book III (1845 – 46), a. Instruction 5, Christ’s Church infallible; b. Instruction 6, Protestant principles lead to infallible Church, yet they do not claim infallibility. 50.04 Instruction Book IV (1845 – 46), a. Instruction 7, The Roman Catholic Church as the infallible Church of Christ; b. Instruction 8, The Unity of the Church established by Christ 50.05 Instruction Book V (1845 – 46), a. Instruction 9, The Protestant’s lack of unity; b. Instruction 10, Unity of Catholic Church flows primarily from Church 50.06 Instruction Book VI (1845 – 46), a. Instruction 11, Unity of the Catholic Church; b. Instruction 12, Possession of “Sanctity” in Catholic Church; lack of it in the Protestant Church 50.07 Text on dedication of an altar 50.08 Text on Saint Patrick 50.09 Instruction Book I (1846 – 47), a. -

Southwark Roman Catholic Diocesan Archives

GB0411 HMC Southwark Roman Catholic Diocesan Archives This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 27760 The National Archives 277641 NATIOttA'. REQTITBII OP SOUTHWARK DIOCESAN ARCHIVES ARCHIVES Personal papers and special collections This list of papers seen at Archbishop's House, Southwark in July 1984 supplements the description of the archives by the Rev Michael Clifton in Catholic Archives, 4, 1984, ppl5-24. All enquiries concerning the papers should be addressed to Father Clifton, Diocesan Archivist, c/o Archbishop's House, St George's Road, Southwark, London SE1 6HX. Personal papers of vicars apostolic and of bishops of Southwark BRAMSTON, James Yorke (1763-1836). Vicar apostolic London district 1827-36. Letters to him 1835-6 concerning Gibraltar; London district financial papers to 1850 (1 box: Bl). it, io GRANT, Thomas (18M-18M). Bishop of Southwark 1851-70. ^ Military and chaplaincy correspondence 1850-70 (1 box: B4). Correspondence with Admiralty, Colonial, Foreign and War Offices, incl material rel to Crimean War (3 boxes: B5). Letters to him 1852-69, incl from John Briggs 1852-9, John Morris 1866-8, James Brown 1859-66 (1 box: no number). Correspondence and papers rel to family affairs, Achilli case; letters to him mainly rel to Irish affairs 1856-66 (1 box: B2) Letters to him in Rome 1869-70, mainly from James Dan^ell, a few from Cornelia Connelly; printed material (1 box: nn). Ad Clera (2 boxes: A, B). Financial papers (1 box: nn). Wills, bequests, executorship and guardianship papers (1 box: B3) DAN^ELL, James (1821-1835). -

Religion: Scandal Revisited One Morning in 1840 in Grand Coteau, La., a Young Mother Shooed Her 2½-Year-Old Son Outside to Play with His Big Newfoundland Dog

Religion: Scandal Revisited One morning in 1840 in Grand Coteau, La., a young mother shooed her 2½-year-old son outside to play with his big Newfoundland dog. Somehow, tumbling about with the dog, the boy got too near a boiling sugar vat and fell in. He was 43 hours dying. In his mother's diary, his death and the long watch at his bedside are recorded in three stark words: "Sacrifice! Sacrifice! Sacrifice!" The child's death was a bitter milepost in the life of an extraordinary woman—a life that began in a fashionable, upper-class Episcopal home in Philadelphia, ended in an English Roman Catholic convent, and may be crowned by beatification by the Roman Catholic Church. In The Case of Cornelia Connelly (Pantheon; $3.75), British Roman Catholic Author Juliana Wadham brings back to life a reverberating scandal that burst upon the U.S. and Britain in 1849, when the Catholic Church was struggling to re- establish itself in England. Ready to Submit. To gay, pretty Cornelia Connelly, her son's death was a clear and overpowering answer to a prayer she had made the day before: she felt that she was too joyous and too fortunate, and asked to be allowed a sacrifice to give her love of God a deeper meaning. The source of both Cornelia's joy and piety, and the corrosive catalyst of the remainder of her turbulent life, was her husband Pierce Connelly, a charming, hypnotically persuasive ecclesiastical eclectic. A young Episcopal clergyman from Philadelphia, Pierce showed intense ambition from the time he married wellborn, well-educated Cornelia Peacock in 1831. -

CATHOLIC CONVERSION and ENGLISH IDENTITY a Dissertation

“I HAVE NOT A HOME:” CATHOLIC CONVERSION AND ENGLISH IDENTITY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Teresa Huffman Traver, B.A. Chris Vanden Bossche, Director Graduate Program in English Notre Dame, Indiana July 2007 © Copyright 2007 Teresa Huffman Traver “I HAVE NOT A HOME:” CATHOLIC CONVERSION AND ENGLISH IDENTITY Abstract By Teresa Huffman Traver Throughout the nineteenth century, religious identity, national identity, and domesticity converge in the depiction of broken homes, foreign invaders, and homeless converts which abound in anti-Catholic literature. This literature imagines conversion to Roman or Anglo-Catholicism as simultaneously threatening the English home and the English nation through the adoption of the anti-domestic practices of celibacy and monasticism. However, constructions of conversion as a rejection of domesticity and English identity were not limited to anti-Catholic propaganda: mainstream novelists made use of stock anti-Catholic tropes for rather more complicated purposes. In light of this convergence between religion, nation, and home, this dissertation explores novels by John Henry Newman, Margaret Oliphant, Charlotte Yonge, and Charlotte Brontë in the context of mid-century journal and newspaper articles, court cases, religious tracts and popular anti-Catholic fiction. I argue that in literature concerned with Catholic conversion and the Tractarian movement, the trope of finding a home became a tool for imagining new domestic, Teresa Huffman Traver religious, and national communities. Victorian constructions of English national identity and domesticity were always mutually constitutive, as domesticity was understood to be one of the identifying markers of “Englishness,” while the home served as a microcosm of the nation. -

Yes, Lord, Alwaysy Es

Yes, Lord, AlwaysY es Yes, Lord, AlwaysY es A Life of Cornelia Connelly 1809 - 1879 Founder of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus by Elizabeth Mary Strub, shcj Casa Cornelia Publications San Diego, CA, USA © Society of the Holy Child Jesus Via Francesco Nullo, 6 00152 Rome - Italy All rights reserved. First published, January 2003 Fourth printing, March 2021 Contents Preface ................................................................................. v Dedication ......................................................................... vii Background .........................................................................1 At the Montgomery’s ............................................................4 The Minister Takes a Wife....................................................6 More About Pierce .............................................................11 Several Months in Suspense ...............................................15 From New Orleans to Rome ..............................................17 Journey to the Center ........................................................20 The Cosmopolitan Life ......................................................24 Beginning Again ................................................................31 Together in Grand Coteau ..................................................33 A Crucial Year ....................................................................37 Apart Together ...................................................................43 Two Continents, Two Lives ................................................47 -

Pope Francis to the United States of America and the United Nations

Resources Apostolic Journey of Pope Francis to the United States of America and the United Nations September 22-27, 2015 Compiled by: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops; Archdiocese of Washington; Archdiocese of New York; Archdiocese of Philadelphia #PopeInUS #PapaEnUSA CONTENTS Schedule of Events .............................................................................................................. 3 Biography of Pope Francis……………………………………………………………...…5 Archdiocese of Washington Press Kit ................................................................................ 6 Archdiocese of New York ................................................................................................ 22 Archdiocese of Philadelphia ............................................................................................. 44 USCCB Officers…………………………………………………………………………56 Papal Visit 2015 Communications Contacts..................................................................... 62 History of the Catholic Church in the United States......................................................... 65 Papal Visits to the United States ...................................................................................... 68 Bishops and Dioceses ....................................................................................................... 70 Catholic Education ............................................................................................................ 76 Clergy and Religious........................................................................................................ -

Cornelia Connelly

Non-Profit US Postage PAID 1341 Montgomery Avenue Chester, PA Rosemont, PA 19010 Permit No. 170 1809 -1879 ChildJesus Holy the Society of Founder, Connelly Cornelia Prayer to Obtain the Beatification Of Venerable Cornelia Connelly O God, who chose Cornelia Connelly to found the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, inspiring her to follow the path marked out by your divine son, obedient from the crib to the cross, let us share her faith, her obedience and Portrait by Ellen Cooper, 2007 her unconditional trust Society of in the power of your love. The Holy Child Jesus Grant us the favor Generalate Office we now implore Casa Cornelia through her intercession… Via della Maglianella 379 • 00166 Rome, Italy and be pleased to glorify, African Province Office even on earth, P. O. Box 52465 Ikoyi your faithful servant, COVER Lagos Code 100001 • Nigeria, West Africa through the same Stained Glass Window, Rosemont College, Christ our Lord. Rosemont, PA. American Province Office 1341 Montgomery Avenue Installed in College Chapel, 1941 Amen. Rosemont, PA 19010 • USA European Province Office Victoria Charity Centre Please report any favors requested 11 Belgrave Road • London SW1V 1RB, England and/or favors received to one of the addresses at the back of the booklet. Life does not always turn out the way we imagined. Sometimes life exceeds our expectations, leading us in directions more fulfilling than we could ever have dreamed. But life can also turn us upside down, betraying us in ways that leave us disoriented, reeling and wary. Even when our dreams are realized, they usually come to pass only after false starts, twists and turns along the way and lots of hard work. -

Inside This Issue: Associate Upcoming Events Blessings Abound!

SHCJ ASSOCIATES NEWSLETTER AMERICAN PROVINCE DECEMBER, 2007 VOLUME V, ISSUE 4 Blessings Abound! As we reach the final days of 2007, we count the many blessings of the year. In many ways, 2007 was a significant year for the Associate relationship. It was a year of many firsts! Several Associates made formal commitments in the Associate relationship for the first time. Others have begun the journey toward commitment in 2008. Electronic monthly eUpdates began in January and each issue continues to share news about Associates with SHCJ Sisters and Associates. Our web site had a major upgrade and now allows us to share thoughts and ideas on a variety of changing topics. To get to know the individuals who have entered into the Associate relationship with the Society, the first SHCJ Associate directory was published for the United States. Of course, all of these are ways to connect us to one another and ultimately to enhance the Associate relationship. This Advent and Christmas season, many Associates are joining with SHCJ in praying and reflecting on the Incarnation with the Our Dear Retreat materials. What a wonderful way to link us all together as we know that SHCJ Sisters and Associates around the world are praying the same prayers and reflecting with a similar focus. I am sure that I speak for all Associates as we thank the Society for their generosity in supporting the Associate relationship. Through the support and inspiration of individual sisters and the generosity of the Provincial Leadership Team, Associates are assisted in deepening our relationships with our loving God. -

Director's Handbook

For Members of the RESPONSE-ABILITY Dominican Republic Service Program Updated 6-15-06 Table of Contents Section 1 MISSION OF RESPONSE-ABILITY...................................3 Mission Statement.....................................................................4 Belief Statements.......................................................................5 Foundations of Response-Ability..............................................6 SHCJ Terminology....................................................................8 Section 2 COMMUNITY LIVING WITH RESPONSE-ABILITY.....9 Community Commitment........................................................10 General Information about Response-Ability Houses.............10 ABC’s of Practical Matters in Community..............................11 Section 3 PROGRAM INFORMATION.............................................13 RA Staff Members...................................................................14 ABC’s of Practical Matters of the Program.............................15 Section 1 RESPONSE-ABILITY Handbook Mission of Response-Ability Mission of RA RA Vision Communities modeling reverence for each individual RA Mission A ministry of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus grounded in Cornelia Connelly’s edu- cational philosophy, Response-Ability trains, coaches and inspires innovative volunteer teachers to provide quality education in inner city schools and international sites. Living in community, volunteers achieve spiritual, personal and professional growth. RA Values Response-Ability values: