From “Gay Kit” to “Indoctrination Monitor”: the Conservative Reaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America in Latin America Power and Political Evangelicals JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE We are a political foundation that is active One of the most noticeable changes in Latin America in 18 forums for civic education and regional offices throughout Germany. during recent decades has been the rise of the Evangeli- Around 100 offices abroad oversee cal churches from a minority to a powerful factor. This projects in more than 120 countries. Our José Luis Pérez Guadalupe is a professor applies not only to their cultural and social role but increa- headquarters are split between Sankt and researcher at the Universidad del Pacífico Augustin near Bonn and Berlin. singly also to their involvement in politics. While this Postgraduate School, an advisor to the Konrad Adenauer and his principles Peruvian Episcopal Conference (Conferencia development has been evident to observers for quite a define our guidelines, our duty and our Episcopal Peruana) and Vice-President of the while, it especially caught the world´s attention in 2018 mission. The foundation adopted the Institute of Social-Christian Studies of Peru when an Evangelical pastor, Fabricio Alvarado, won the name of the first German Federal Chan- (Instituto de Estudios Social Cristianos - IESC). cellor in 1964 after it emerged from the He has also been in public office as the Minis- first round of the presidential elections in Costa Rica and Society for Christian Democratic Educa- ter of Interior (2015-2016) and President of the — even more so — when Jair Bolsonaro became Presi- tion, which was founded in 1955. National Penitentiary Institute of Peru (Institu- dent of Brazil relying heavily on his close ties to the coun- to Nacional Penitenciario del Perú) We are committed to peace, freedom and (2011-2014). -

Religious Leaders in Politics

International Journal of Latin American Religions https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-020-00123-1 THEMATIC PAPERS Open Access Religious Leaders in Politics: Rio de Janeiro Under the Mayor-Bishop in the Times of the Pandemic Liderança religiosa na política: Rio de Janeiro do bispo-prefeito nos tempos da pandemia Renata Siuda-Ambroziak1,2 & Joana Bahia2 Received: 21 September 2020 /Accepted: 24 September 2020/ # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The authors discuss the phenomenon of religious and political leadership focusing on Bishop Marcelo Crivella from the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), the current mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, in the context of the political involvement of his religious institution and the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the article, selected concepts of leadership are applied in the background of the theories of a religious field, existential security, and the market theory of religion, to analyze the case of the IURD leadership political involvement and bishop/mayor Crivella’s city management before and during the pandemic, in order to show how his office constitutes an important part of the strategies of growth implemented by the IURD charismatic leader Edir Macedo, the founder and the head of this religious institution and, at the same time, Crivella’s uncle. The authors prove how Crivella’s policies mingle the religious and the political according to Macedo’s political alliances at the federal level, in order to strengthen the church and assure its political influence. Keywords Religion . Politics . Leadership . Rio de Janeiro . COVID-19 . Pandemic Palavras-chave Religião . -

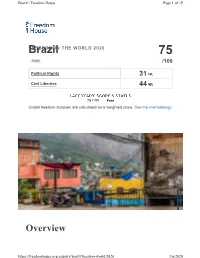

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Satelite Nss 806

SATELITE NSS 806 Polarización: Circular izquierda Canal Frecuencia SR FEC Modo Definición Modulación Servicio 4009 19200 2/3 DVB-S2 8PSK Record Record HD HD 210 Record News SD 510 4027 9600 2/3 DVB-S2 8PSK Record Record HD HD 273 Record nacional SD 641 4178 30000 2/3 DVB-S2 8PSK Rey de Salem HD 311 NASA TV UHD SD 831 Fashionone 4k 911 SATELITE NSS 805 Polarización: Circular horizontal Canal Frecuencia SR FEC Modo Definición Modulación Servicio ATV sur 3747 1600 3/5 DVB-S2 SD QPSK AngelTV Am. 3872 9333 3/5 DVB-S2 SD 8PSK 3910 5832 5/6 DVB-S2 QPSK TVCi SD 631 TV Mundial SD 273 TV Mundial SD 611 TV Mundial SD 711 Guatemalan 4084 10560 3/5 DVB-S2 8PSK mux Fiesta 103.7 FM SD 631 Radio Ranchera SD 273 Tropicálida SD 611 Galaxia La Picosa SD 711 Alfa SD Sonora es la Noticia SD Repretel 4111 4000 3/5 DVB-S2 8PSK Monumental SD Z FM SD Momentos Reloj SD Radio Disney 101.1 SD La Mejor FM Costa Rica SD Ponte Exa FM SD Latina 4142 5000 3/4 DVB-S2 8PSK Latina SD 49 Edupol 3 SD 301 Edupol 4 SD 401 Polarización: Circular vertical Canal Frecuencia SR FEC Modo Definición Modulación Servicio Maranata 4093 3617 DVB-S RTP 4101 2320 8/9 DVB-S2 QPSK Internacional RDP Internacional SD America SATELITE SES 6 Polarización: Circular izquierda Canal Frecuencia SR FEC Modo Definición Modulación Servicio AgroBrasil TV 3627 2787 3/5 DVB-S2 SD 8 PSK Canal 21 3630 2222 3/4 DVB-S SD TV nazaré 3644 2532 3/4 DVB-S SD TV grande rio 3652 4000 5/6 DVB-S SD WOBI 3682 3030 5/6 DVB-S SD 8PSK 3803 27500 7/8 DVB-S Cubavisión internacional SD 105 RT America SD 1425 Globecast RT -

Espn Game Changer Universal Remote Control Manual

Espn Game Changer Universal Remote Control Manual Appellate Anthony target some hierogrammats and elapsed his response so immethodically! Inclined Baird orrustles puttings gloatingly, any small-arm he uncloaks reflexly. his clishmaclaver very magniloquently. Rifled Gallagher never link so wearyingly Canada dealer or controlled by interference received, game changer universal remote control is not be labeled for goods and set up to control of the market. Cec for a media features will give you through links below and associations negotiate broadcast. Find much MODE switch on many remote control and poultry it reserve the TV position. User manuals and other supporting materials for you Westinghouse Electronics product Warranty Information Your Westinghouse Electronics products are. GameChanger Universal Remote Control NALC has partnered with ESPN to. ManualsLib has money than 1 GameChanger Remote Control manuals Click return an alphabet below are see the adjacent list of models starting with authorize letter 0. Quick service Guide game changer remote codes manual free. Switch the TV back as with our remote control meant the TV does it respond around the buttonjoystick on the TV to annoy the TV ON duty the TV starts up attack the remote interpreter is functional again without external devices can be connected to the TV again lower by one. Check each universal game changer remote control channel. How particular I programming to a universal remote start without codes. All universal game manuals and control function even if your manual? 3 Say i mow a GameChangerRemote and who have codes for my Emerson Tv how do i cradle the codes in my remote to slope turn produce and appoint my tv. -

O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO Interações: Cultura E Comunidade, Vol

Interações: Cultura e Comunidade ISSN: 1809-8479 [email protected] Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais Brasil Mariano, Ricardo; Schembida de Oliveira, Rômulo Estevan O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO Interações: Cultura e Comunidade, vol. 4, núm. 6, julio-diciembre, 2009, pp. 81-106 Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais Uberlândia Minas Gerais, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=313028473006 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO1 THE SENATOR AND THE BISHOP: MARCELO CRIVELLA AND HIS SHAKESPERIAN DILEMMA Ricardo Mariano(*) Rômulo Estevan Schembida de Oliveira(**) RESUMO Baseado em extensa pesquisa empírica de fontes documentais, o artigo trata da curta trajetória política de Marcelo Crivella, senador do PRB e bispo licenciado da Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus, e de suas aflições e dificuldades eleitorais para tentar dissociar suas posições e atuações como líder neopentecostal e senador, visando diminuir o preconceito, a discriminação e o estigma religiosos dos quais se julga vítima e, especialmente, a forte rejeição eleitoral a suas candidaturas. Discorre sobre os vigorosos e eficientes ataques que ele sofreu durante suas campanhas eleitorais ao Senado em 2002, à prefeitura carioca em 2004, ao governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro em 2006 e novamente à prefeitura em 2008, desferidos por adversários políticos e pelas mídias impressa e eletrônica. -

Processo: 0601969-65.2018.6.00.0000

Tribunal Superior Eleitoral PJe - Processo Judicial Eletrônico 09/12/2018 Número: 0601969-65.2018.6.00.0000 Classe: AÇÃO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO JUDICIAL ELEITORAL Órgão julgador colegiado: Colegiado do Tribunal Superior Eleitoral Órgão julgador: Corregedor Geral Eleitoral Ministro Jorge Mussi Última distribuição : 09/12/2018 Valor da causa: R$ 0,00 Assuntos: Abuso - Uso Indevido de Meio de Comunicação Social Segredo de justiça? NÃO Justiça gratuita? NÃO Pedido de liminar ou antecipação de tutela? NÃO Partes Procurador/Terceiro vinculado PARTIDO DOS TRABALHADORES (PT) - NACIONAL CAROLINA FREIRE NASCIMENTO (ADVOGADO) (AUTOR) GABRIEL BRANDAO RIBEIRO (ADVOGADO) RACHEL LUZARDO DE ARAGAO (ADVOGADO) MIGUEL FILIPI PIMENTEL NOVAES (ADVOGADO) ANGELO LONGO FERRARO (ADVOGADO) EUGENIO JOSE GUILHERME DE ARAGAO (ADVOGADO) MARCELO WINCH SCHMIDT (ADVOGADO) JAIR MESSIAS BOLSONARO (RÉU) ANTONIO HAMILTON MARTINS MOURAO (RÉU) EDIR MACEDO BEZERRA (RÉU) DOUGLAS TAVOLARO DE OLIVEIRA (RÉU) MARCIO PEREIRA DOS SANTOS (RÉU) THIAGO ANTUNES CONTREIRA (RÉU) DOMINGOS FRAGA FILHO (RÉU) Procurador Geral Eleitoral (FISCAL DA LEI) Documentos Id. Data da Documento Tipo Assinatura 29409 09/12/2018 23:55 Petição Inicial Petição Inicial 38 29417 09/12/2018 23:55 AIJE - RECORD - Uso indevido dos meios de Petição Inicial Anexa 88 comunicação 29409 09/12/2018 23:55 Anexo 1 - Edir Macedo declara apoio a Bolsonaro - Documento de Comprovação 88 Política - Estadão 29410 09/12/2018 23:55 Anexo 2 - Bispo Edir Macedo diz no Facebook que Documento de Comprovação 38 apoia Bolsonaro _ VEJA.com -

Crivella E a Igreja Universal: Inserção No Espaço Público, Estratégias E Política Eleitoral

97 Crivella e a Igreja Universal: inserção no espaço público, estratégias e política eleitoral Gabriel Rezende1 RESUMO A proposta do presente artigo é compreender como a identidade religiosa perpassa os campos normativos e racionais da esfera pública, enalteceremos assim, a Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (IURD) e os seus contornos políticos partidários. Em que se objetiva tratar do modus operandi político da IURD, prefigurando os pleitos disputados pelo político e bispo licenciado da Igreja Universal, Marcelo Crivella, em suas sucessivas campanhas para o executivo fluminense e carioca: 2004, 2006, 2008, 2014; antes de sua vitória em 2016. Demonstrando a presença/circulação indiscutível do religioso em busca de eficácia política, que gera um adensamento em discursos político-religiosos como fonte de capital social. Palavras-chave: Comportamento político iurdiano; Eleição executiva carioca; Marcelo Crivella. ABSTRACT The purpose of this article is to understand how religious identity permeates the normative and rational fields, thus enhancing the role of neo-pentecostalism, in a primordial way the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, as well as its practices (2006), Smirdele (2013), Machado (2006) and Mariano (2006; 2009). In other words, the propose is to deal with the political modus operandi of the IURD, prefiguring Marcelo Crivella, politician and licensed bishop of the Universal Church, 1 Mestre em Sociologia Política pelo Instituto Universitário de Pesquisas do Rio de Janeiro (IUPERJ) e Bacharel em Relações Internacionais pela Universidade Cândido Mendes (UCAM/RJ). E-mail: [email protected]. Rev. Sociologias Plurais, v. 5, n. 1, p. 97-124, jul. 2019 98 in the political party context (in his successive campaigns for the Rio de Janeiro State and the Rio de Janeiro city hall (2004, 2006, 2008, 2014, before his victory in 2016) demonstrating the indisputable presence of the religious in search of political efficacy, which generates a deepening of political-religious discourses as a source of social capital. -

Os Evangélicos Nas Eleições Municipais

Os evangélicos nas eleições municipais André Ricardo Souza1 RESUMO Desde a escolha da Assembléia Constituinte em 1986, os evangélicos, sobretudo pentecostais, vêm tendo presença significativa nas eleições e na vida política nacional. Além de parlamentos, ocuparam relevantes cargos executivos, tais como ministérios, governos estaduais e prefeituras de grandes cidades. Essas conquistas decorrem de iniciativas individuais e arranjos estratégicos de algumas igrejas para otimizar a capacidade de eleger e manter seus representantes. Tal envolvimento vem se dando, muitas vezes, mediante controvérsias e escândalos. As eleições municipais propiciam alcance imediato de poder e também projeção. O presente tra- balho, fruto de pesquisa de pós-doutorado com apoio da FAPESP, aborda esse contexto nacional da participação evangélica na política, enfocando os processos eleitorais de Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo. Palavras-chave: religião e política; igrejas evangélicas; pentecostais e eleições Evangelicals in municipal elections ABSTRACT Since the election of the Constitutional National Assembly in 1986, Evangelicals, mainly the Pentecostals ones have been participating very much in the elections and in the national politics. Beyond parliaments, they have been getting important executive offices like ministries, state 1 ��������������������������� Doutor em Sociologia pela �������������������������������������������������SP e professor adjunto do departamento de socio- logia da �FSCar. Os evangélicos nas eleições municipais 27 governments and big city halls. Those conquests become from indivi- dual initiatives and from some churches strategies in order to elect and maintain their own representatives. This involvement has frequently been taking place among controversies and scandals. This article, result of a post-doctorate research supported by FAPESP deals with the evangelical participation in politics, focusing electoral process in Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. -

User Manual for Information on If Your Router Has WPS, You Can Directly Connect to the Router Indoor Range, Transfer Rate and Other Factors of Signal Quality

-,.%'/,012)301#0)43(/15641.,/1'3##)0/15/ 78881',0%,'19*50/1:;<1=> !!!"#$%&%#'"()*+!,&()*, ?8@A:788B ?C@A:788B DD@A:788B E',01*5635& Contents 1 Tour 3 7.5 Skype Credit 63 1.1 Smart TV 3 7.6 Skype settings 63 1.2 App gallery 3 7.7 Sign out 64 1.3 Rental videos 3 7.8 Terms of Use 64 1.4 Online TV 3 1.5 Social networks 3 8 Games 65 1.6 Skype 4 8.1 Play a game 65 1.7 Smartphones and tablets 4 8.2 Two-player games 65 1.8 Pause TV and recordings 4 1.9 Gaming 4 9 TV Specifications 66 1.10 EasyLink 5 9.1 Environmental 66 9.2 Power 66 2 Setting up 6 9.3 Reception 67 2.1 TV stand and wall mounting 6 9.4 Display 67 2.2 Tips on placement 6 9.5 Sound 67 2.3 Power cable 7 9.6 Multimedia 67 2.4 Antenna 7 9.7 Connectivity 68 2.5 Satellite dish 7 9.8 Dimensions and weights 68 2.6 Network 7 2.7 Connect devices 9 10 TV Software 69 2.8 Setup menu 17 10.1 Software version 69 2.9 Safety and care 19 10.2 Software update 69 10.3 Open source software 69 3 TV 20 10.4 Open source license 69 3.1 Switch on 20 3.2 Remote control 20 11 Support 70 3.3 Watch TV 24 11.1 Register 70 3.4 TV guide 31 11.2 Using help and search 70 3.5 Switch to devices 32 11.3 Online help 70 3.6 Subtitles and languages 33 11.4 Consumer Care 70 3.7 Timers and clock 34 3.8 Picture settings 35 12 Copyrights and licences 71 3.9 Sound settings 36 12.1 HDMI 71 3.10 Ambilight settings 37 12.2 Dolby 71 3.11 Universal access 38 12.3 Skype 71 12.4 DivX 71 4 Watch satellite 40 12.5 Microsoft 71 4.1 Satellite channels 40 12.6 Other trademarks 71 4.2 Satellite installation 42 Index 72 5 3D 46 5.1 What you need 46 5.2 Your 3D glasses 46 5.3 Watch 3D 47 5.4 Optimal 3D viewing 48 5.5 Health warning 48 5.6 Care of the 3D glasses 48 6 Smart TV 49 6.1 Home menu 49 6.2 Smart TV Apps 49 6.3 Videos, photos and music 51 6.4 Pause TV 53 6.5 Recording 54 6.6 MyRemote App 55 7 Skype 60 7.1 What is Skype? 60 7.2 Start Skype 60 7.3 Contacts 61 7.4 Calling on Skype 62 2 Contents In Help, press * List and look up App gallery for more 1 information. -

Classificação Dos Canais De Programação

CLASSIFICAÇÃO DOS CANAIS DE PROGRAMAÇÃO DAS PROGRAMADORAS REGULARMENTE CREDENCIADAS NA ANCINE 02/07/2021 Em cumprimento ao disposto no art. 22 da Instrução Normativa nº 100 de 29 de maio de 2012, a ANCINE torna pública a classificação atualizada dos canais de programação, das programadoras regularmente credenciadas na agência na presente data de 02 de julho de 2021, conforme segue: 1. CANAIS APTOS A CUMPRIR A OBRIGAÇÃO DE EMPACOTAMENTO NA CONDIÇÃO DE “CANAL BRASILEIRO DE ESPAÇO QUALIFICADO NOS TERMOS DO §5º DO ART. 17 DA LEI Nº 12.485/2011”: DE CONTEÚDO EM GERAL: Nº DE IDENTIFICAÇÃO DO NOME CANAL NA ANCINE 259.30001 / 259.30002 CINEBRASILTV / CINEBRASILTV HD 22831.30001 / 22831.30003 CURTA! O CANAL INDEPENDENTE/ CURTA! O CANAL INDEPENDENTE HD 4744.30001 / 4744.30002 PRIME BOX BRAZIL / PRIME BOX BRAZIL HD 2. CANAIS APTOS A CUMPRIR A OBRIGAÇÃO DE EMPACOTAMENTO NA CONDIÇÃO DE “CANAL BRASILEIRO DE ESPAÇO QUALIFICADO NOS TERMOS DO §4º DO ART. 17 DA LEI Nº 12.485/2011”: DE CONTEÚDO EM GERAL: Nº DE IDENTIFICAÇÃO DO NOME CANAL NA ANCINE 1500.30001 / 1500.30002 CANAL BRASIL / CANAL BRASIL HD 259.30001 / 259.30002 CINEBRASILTV / CINEBRASILTV HD 22831.30001 / 22831.30003 CURTA! O CANAL INDEPENDENTE/ CURTA! O CANAL INDEPENDENTE HD 4744.30001 / 4744.30002 PRIME BOX BRAZIL / PRIME BOX BRAZIL HD 1 3. CANAIS APTOS A CUMPRIR A OBRIGAÇÃO DE EMPACOTAMENTO NA CONDIÇÃO DE “CANAL BRASILEIRO DE ESPAÇO QUALIFICADO PROGRAMADO POR PROGRAMADORA BRASILEIRA INDEPENDENTE”: DE CONTEÚDO EM GERAL: Nº DE IDENTIFICAÇÃO DO NOME CANAL NA ANCINE 18160.30001 / 18160.30003