Download Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Northwest Kidney Centers ranks high in national ratings of dialysis quality SEATTLE, Wash. (Oct. 27, 2016): The patient care provided at Northwest Kidney Centers dialysis clinics is among the best in the nation, according to the annual Dialysis Facility Compare five-star quality rating system of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The nonprofit operates 15 dialysis clinics in King and Clallam counties. Fourteen of the clinics received 4 or 5 stars. The overall star rating for the organization is 4.3, an average of the stars awarded to individual clinics. The federal government ratings cover every dialysis center in the United States. They are based on 2015 patient outcomes related to survival, hospitalizations, management of anemia, vascular access and management of bone disease. “We are pleased that our quality is high and getting better,” said Northwest Kidney Centers president and CEO Joyce F. Jackson. “Our mission is to promote the optimal health, quality of life and independence of people with kidney disease. It’s good to have concrete data to show we are on the right track.” Statistics from the federal Dialysis Facility Reports for our facilities show: • Northwest Kidney Centers patients are hospitalized 16 percent less often than the national average. • Northwest Kidney Centers patients receive transplants at a rate 70 percent higher than others across the country. • Compared to their counterparts across the country, Northwest Kidney Centers patients are much more likely (37 percent vs. 25 percent) to start dialysis with a permanent bloodstream access for hemodialysis. This access method is considered the gold standard because it’s less infection-prone than a temporary catheter. -

Dialysis Connection Volume 2, Issue 4 · Fall 2013

Dialysis Connection volume 2, issue 4 · Fall 2013 if weather outside is frightful . Have a plan in case of emergency emergency supply kit if bad weather or a disaster hits, will you be ready? Winter weather for home can be a serious problem if it gets in the way of your dialysis treatments. Here are a few simple steps you can take to prepare for a emergency diet food supply for the season ahead. three to five days Ask your dietitian about the emergency diet plan in case you a Paper or plastic plates, cups, can’t get to dialysis. Shop for the right foods to survive. bowls, eating utensils Stock up on medications. Always keep a week’s supply on hand. a non-electric can opener Keep a current list of contact information. List your dialysis a Aluminum foil center, doctor, dietitian, friends and relatives. Make sure your unit has three different ways to reach you. a Battery-operated radio Have a backup transportation plan for getting to dialysis if a Flashlight normal travel plans fall through. a extra batteries Create an emergency supply kit. See column at right. a candles and matches in waterproof container a First aid kit a Sharp knife and scissors a Paper towels a Baby or sanitary wipes a Garbage bags a Gallon jugs of distilled water (one gallon per person) a Bleach and eyedropper to purify water (16 drops per gallon of water) etta Barwee gets dialysis at our Seattle center, at 15th and cherry. 2 Dialysis Connection Is your next step home dialysis or a kidney transplant? Find out at a free class Home dialysis offers many conveniences “We found the classes very good and On home dialysis, you won’t worry about bad weather informative. -

CN App #18-49 Northwest Kidney Centers King

YEAR 2018 CYCLE 1 NON-SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCE EVALUATION DATED MAY 3, 2019, FOR THE FOLLOWING THREE CERTIFICATE OF NEED APPLICATIONS PROPOSING TO ADD DIALYSIS STATION CAPACITY IN KING COUNTY PLANNING AREA #1 • NORTHWEST KIDNEY CENTERS PROPOSING TO ADD 19 DIALYSIS STATIONS TO NKC LAKE CITY KIDNEY CENTER IN LAKE FOREST PARK • PUGET SOUND KIDNEY CENTERS PROPOSING TO ESTABLISH A 19-STATION DIALYSIS CENTER IN SHORELINE • DAVITA, INC PROPOSING TO ESTABLISH A 19-STATION DIALYSIS CENTER IN SEATTLE APPLICANT DESCRIPTIONS Northwest Kidney Centers Northwest Kidney Centers (NKC) is a private, not-for-profit corporation, incorporated in the state of Washington. Established in 1962, NKC operates as community based dialysis program working to meet the needs of dialysis patients and their physicians. A volunteer board of trustees governs NKC and the board is comprised of medical, civic and business leaders from the community. An appointed Executive Committee of the Board oversees operating policies, performance and approves capital expenditures for all of its facilities. [source: CN historical files and Application, p3 and Exhibits 1 and 2] NKC provides dialysis services through its facilities located in King, Clallam, and Pierce counties and does not own or operate any healthcare facilities outside of Washington State. In Washington State, NKC is approved to own and operated 17 kidney dialysis facilities.1 Of the 17 facilities, 15 are located within King County; one in Pierce County; and one in Clallam.2 Below is a listing of NKC’s dialysis facilities in -

Read Full Report Here

Our Vision and Accomplishments Transforming lives through innovation and discovery The Kidney Research Institute is a collaboration between Northwest Kidney Centers and UW Medicine OUR TRANSITIONING GOAL TO A NEW ERA To establish a leading clinical OF GROWTH research endeavor focusing on AND DISCOVERY early detection, prevention and As we come to the end of our startup phase, we continue to work to find better ways to treatment of kidney disease detect kidney disease, to slow its progression and its complications. and to create optimal treatments. Making every dollar count Thanks to generous donor support, our OUR interdisciplinary teams of top-notch scientists and clinical practitioners aggressively seek VISION new approaches to identifying, preventing and treating the kidney disease epidemic. For every eligible patient with kidney disease to be informed The need for research Dr. Jonathan Himmelfarb, first director about, participate in and benefit For millions of people with kidney disease, of the Kidney Research Institute and from our research. kidney failure is not the only concern. Kidney a University of Washington professor disease is linked to premature cardiovascular of medicine, also holds the Joseph W. disease, fractures, infections and diminished Eschbach, M.D. Endowed Chair in physical and mental functioning. Kidney Research at UW Medicine. OUR Carrying out our mission Dr. Himmelfarb has been a leader in clinical trials in the kidney disease Ultimately, we aim to translate our population, serves on expert panels for MISSION discoveries into direct and improved care for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration To conduct research that can the patient. We are guided by a Scientific Advisory Committee of top thought leaders, and Veterans Health Administration, has improve the lives of those with and a Council that keeps us in close touch leadership roles on National Institutes kidney disease. -

Community Connection Volume 8, Issue 4 · Fall 2018 Committed to Research in the 10 Years of the Kidney NON PROFIT ORG Research Institute’S Existence, U.S

www.nwkidney.org Pharmacy: [email protected] 206-343-4870 206-292-2771 1-800-947-8902 Northwest Kidney Centers promotes the optimal health, quality of life and independence of people with kidney disease through patient care, education and research. Community Connection Volume 8, Issue 4 · Fall 2018 Committed to research In the 10 years of the Kidney NON PROFIT ORG Research Institute’s existence, U.S. POSTAGE Precision medicine may suggest INSIDE THIS ISSUE PAID Northwest Kidney Centers has 700 Broadway • Seattle WA 98122 SEATTLE WA PERMIT NO 3768 invested $10 million in kidney individualized kidney treatments RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED research. Going full gala PAGE 2 » Being part of research PAGE 4 » Leading in quality PAGE 6 » The Discovery Gala on Oct. 20 in Bellevue will explore the leading edge of research in a video about the Kidney Precision Medicine Project. Preserving Our Kidney Research Institute has a central role in a large-scale, National Telling our story Institutes of Health (NIH) funded research project that aims to redefine PAGE 8 » a rich history how physicians treat kidney disease. As the world’s first dialysis Across the country, investigators on the Kidney Precision Medicine organization, founded in 1962, Project will collect and evaluate kidney biopsies from people with chronic Northwest Kidney Centers has a kidney disease or acute kidney injury. Biopsy data will be analyzed and keen sense of the history of kidney used to create a kidney tissue atlas, a map of the kidney. Researchers treatment. hope the atlas can change future treatment by allowing physicians to compare data from the biopsies of new patients to the atlas and see how One way we preserve our heritage is to best treat them. -

Dialysis Connection Volume 2, Issue 1 · Winter 2013

Dialysis Connection Volume 2, Issue 1 · Winter 2013 Missing dialysis can be deadly Dialysis replaces your kidney function and removes fluid and To stay as healthy as wastes that build up in your blood. To feel your best, you need to possible while on dialysis: get enough dialysis. Follow your dialysis schedule. Shortening or skipping treatments has serious risks. When Don’t shorten or skip dialysis you miss dialysis, fluids, toxins and potassium build up in your treatments, especially before your bloodstream, making you feel weak. You are more likely to get an two days off. infection. Limit your sodium intake to You may get cramps or low blood pressure at your next dialysis 1,500 milligrams a day. Too session when extra fluid has to be removed. Fluid overload and much salt can cause high blood high potassium levels can lead to trips to the hospital, a need for pressure, which raises the risk of emergency dialysis, and heart complications. heart attack, stroke and arterial disease. High blood pressure You may not notice any problems right away, but not getting can also lead to emergency room enough dialysis will eventually affect your health. Don’t miss visits and hospital stays. a single dialysis treatment without talking to your nurse or nephrologist first. Avoid foods high in phosphorus and take your binders. High phosophorus levels harden blood vessels, which can cause heart attack, stroke and arterial disease. Taking your phosphate binders helps keep the phosphorus in your food from being absorbed into the blood. Get all your prescriptions at our pharmacy: 206-343-4870 [email protected] Getting enough dialysis is essential to your health. -

Bring in The

Community Connection Volume 2, Issue 1 · Winter 2013 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Dialysis equipment for comfort and safety PAGE 2 » New Northwest Kidney Centers clinic to open in Enumclaw PAGE 3 » Dialysis museum debuts at 700 Broadway PAGE 5 » Anayeli Hernandez gets a dialysis treatment at Northwest Kidney Centers Renton, our newest clinic. Eventually all Northwest Kidney Happy memories of Centers clinics will have new-style dialysis chairs like hers. our 50th anniversary celebrations PAGE 6 » Bring in the new Help us replace dialysis equipment for optimal patient care Don’t miss At Northwest Kidney Centers, we are committed to providing a beat patients the best quality of care. A model in the fi eld, we consistently outperform the nation in clinical quality. This means our patients live Follow us and get longer, have better vascular access, get more kidney transplants and the latest news as it spend less time in the hospital. Using state-of-the-art equipment helps happens us continually meet and exceed our quality goals, so over the next several years we are replacing dialysis chairs, dialysis machines and www.nwkidney.org ultrasound machines at our facilities – and you can help. www.facebook.com/ Consider making a donation toward equipment replacement and help northwestkidneycenters us maintain the excellence of our life-sustaining dialysis care. For more information, see page 2. www.twitter.com/ nwkidney 2 Community Connection New dialysis equipment helps patients get the best possible care Dialysis chairs State-of-the-art dialysis chairs offer comfort and safety. We are installing How can you help new Medcor chairs with two folding side tables, built-in lumbar support, Help us replace critical heat, swing-away side arms for easy cleaning and patient transfer, and chair dialysis equipment with your backs that recline so that a patient’s head can be lower than the feet (to gift to Northwest Kidney raise a patient’s blood pressure in an urgent situation). -

What Diabetes Educators Need to Know About the Kidney Disease Diet

What Diabetes Educators need to know about the Kidney Disease diet Jenny Smith, MA, RD, CDE Northwest Kidney Centers, Seattle March 2015 5 Functions of the Kidneys 1. Filter wastes 2. Filter potassium 3. Filter phosphorus/ activate vitamin D 4. Sodium/fluid balance 5. Erythropoietin Filter Protein Wastes Urea (Measured as BUN) . Sent out in urine . From protein breakdown . Buildup causes uremia . Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, confusion, low appetite . Dialysis normal 50-100 . Pre-Dialysis . Targeted protein 0.7g/kg . Acute . Check with MD . Hemodialysis . Protein goals 1-1.2g/kg . Peritoneal Dialysis . Protein goals 1.2-1.5g/kg Nutritional Assessment of Waste Removal .Albumin . Goal > 4.0 . Good measure? . Best measure we have . (not pre-albumin) . Indicator of mortality risk . <2.5 (Lowrie and Lew, 1990) Filter Potassium .Found mostly in fruits and vegetables .Salt substitutes .Dairy (and supplements) .Serum potassium range . Normal 3.5-5.5 . Dialysis 3-6 . Generally 9=death . Things that cause high: diet, skipping dialysis, blood sugars, meds, transfusions, constipation . Things that cause low: vomiting, diarrhea, diuretics, anorexia Filter Phosphorus .Limit high phosphorus foods: . dairy, bran, beans, nuts=1 serving/day ***Processed foods .Take phosphorus binders . Tums, Phoslo, Renvela, Fosrenol *Phoslyra, Velphoro, Keryx .Normal range 2.5-4.8 .Dialysis range 3-6 .Low PO4<1=death .High can cause itching, calcification and calciphlaxis Sodium/Fluid Balance .Kidney balances salt and water volumes via urine output .Regulation of blood pressure • High salt diet=thirst and fluid retention making dialysis fluid removal harder • Is 1500mg a goal? – Is the goal just…less Nutritional Assessment of Fluids .Fluid goal: 3 cups/day + urine output .Fluid gains and dry weight . -

Community Connection Volume 2, Issue 4 · Fall 2013

Community Connection Volume 2, Issue 4 · Fall 2013 InsIDE THIS IssUE: Luke Jackson, patient at Northwest Kidney Centers Be inspired about Lake City, hopes research at Gala that his involvement Page 2 » in research studies will help other kidney patients. Expanding our Eastside presence Page 4 » Looking forward to sunny skies Luke Jackson was working as an electrician and playing electric bass in a Leading the way band when his blood pressure skyrocketed and sent him to the hospital. in bioethics “I knew my blood pressure was high at the time, but I didn’t realize what it Page 6 » would do to me. I had been feeling weak for weeks,” Luke remembers. Soon after that hospital visit two years ago, Luke began dialysis. Today, Free estate he feels much better. He’s exercising again, swimming at the YMCA, planning seminars lifting weights. Page 8 » Luke is involved in a study being conducted by the Kidney Research Institute, a collaboration between Northwest Kidney Centers and UW Medicine. The study examines whether the dietary supplement coenzyme Q10 may lead to improved cardiovascular outcomes in kidney disease patients, who are often at high risk for heart complications. Northwest Kidney For Luke, this means taking four Q10 tablets a day with his meals and Centers Gala getting his blood drawn each month. Saturday, Nov. 16 “I’m all about doing whatever I can to help, if this study will help other people on dialysis. The more knowledge there is about kidney disease, the 5:30 p.m. better we’ll all be. I’m a very optimistic person and I look on the bright side.” Hyatt Regency Bellevue Northwest Kidney Centers is committed to solving the mysteries of kidney www.nwkidney.org/gala disease. -

Dialysis Connection Volume 2, Issue 2 · Spring 2013

Dialysis Connection Volume 2, Issue 2 · Spring 2013 To feel better and prevent problems, control your fluid weight gain Liquids are one of the most important parts of your diet. How Watch that water: much liquid is good for you depends on your urine output, dry tips for handling thirst weight and length of dialysis treatments. If you are unsure what The key to managing your fluid your fluid allowance should be, ask your dietitian or nurse. weight gains is to control your It is normal to gain weight from extra fluid building up in your thirst. Here’s how: body between dialysis treatments. For most people, a good • Avoid salty foods, which make weight gain is 2 to 3 kilograms, depending on body size. The less you thirsty. Salt hides in anything salty food you eat, the lower your fluid weight gains. processed or packaged. Eating salt and drinking too much liquid can lead to problems. • Drink cold liquids instead of Excess fluid built up between dialysis treatments can cause hot ones. swelling, increase your blood pressure and stress your heart. Fluid in your lungs may make it hard to breathe. • Sip beverages slowly to savor the liquid longer. When your care team pulls off a large fluid gain all at once at your next treatment, your blood pressure may drop and you may get • Use small cups or glasses. muscle cramps, headaches and nausea. Sometimes you may even need an extra dialysis session to remove excess fluid. • Snack on ice-cold low- potassium vegetables and To stay comfortable and healthy, be sure to watch your fluid fruits, like chilled berries intake between treatments. -

CDI Campaign to Transform Dialysis

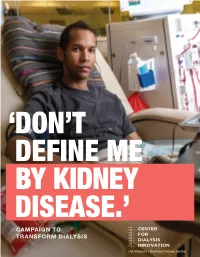

‘ DON’T DEFINE ME BY KIDNEY DISEASE.’ CAMPAIGN TO TRANSFORM DIALYSIS UW Medicine | Northwest Kidney Centers 460,000 people are on dialysis in the U.S. — a $35 billion industry. 24% of the U.S. Medicare budget is spent on treating kidney disease. THIS IS RI DICULOUS. WE NEED TO FIND A BETTER WAY. Jonathan Himmelfarb, MD Buddy Ratner, PhD Kidney disease is the ninth leading cause of death in the United States. While rates of death from heart disease, Co-Director, Center for Dialysis Innovation Co-Director, Center for Dialysis Innovation diabetes and cancer have all decreased significantly in recent years, mortality rates from kidney disease have stayed University of Washington Professor University of Washington Professor the same. Advanced kidney disease is immediately fatal without the support of either dialysis therapy or a kidney of Medicine of Bioengineering transplant. However, access to kidney transplantation is severely rationed due to organ availability and regenerative Joseph W. Eschbach, MD Endowed Chair Michael L. and Myrna Darland Endowed Chair medicine approaches to treating kidney failure remain a distant possibility. Thus, dialysis is the mainstay of treatment in Kidney Research in Technology Commercialization and will likely remain so for the foreseeable future. Unfortunately, dialysis as we know it is not a complete or lasting solution; patients receiving the treatment suffer numerous complications and, on average, survive only three to five years in the United States; in the developing world, survival is much worse and in many cases, dialysis is not even available. Even with poor outcomes, the cost to the U.S. healthcare system for dialysis care exceeds $35 billion annually, and the total cost to society is even greater due to other financial losses associated with undergoing dialysis treatment. -

Vice President of Development Opportunity Guide Organization Overview

Vice President of Development Opportunity Guide www.nwkidney.org Organization Overview Founded in Seattle in 1962, Northwest Kidney Centers Today, NKC has 20 clinic locations across Greater (NKC) is the world’s first dialysis organization. NKC is Seattle. With approximately $150 million in net the provider of choice because of high quality services, revenue, 750 employees, over 600 volunteers and community connections and generous donor support, 105 credentialed staff NKC remains the provider of totaling $4.7 million in gifts in 2020. In 2020, NKC choice in the greater Seattle metro area. NKC has provided approximately 285,000 dialysis treatments which 80 percent market share in King County and is the is about a quarter of all dialysis treatments in the state, eighth largest dialysis organization in the US, in a field for more than 1,800 patients who dialyze in a NKC center dominated by two large for profit organizations. NKC or at home with support. Services offered include is a nationally-recognized brand representing quality hemodialysis, hemodialysis with citrate anticoagulation, and safety including being consistently rated 4+ starts pump ultrafiltration, continuous renal replacement in CMS’ Dialysis Facility Compare. Transplant rates for therapy and peritoneal dialysis. NKC are 60 percent higher than the national average (86 kidney transplants). NKC has unique services for In addition to operating stand-alone dialysis centers, patients that help manage cost and improve quality Northwest Kidney Centers has a 70-member hospital including palliative care, renal pharmacy and services staff that provides dialysis treatments within medication management. eight hospitals including Evergreen Healthcare, Harborview Medical Center, Overlake Medical Center, NKC’s revenue is from payments for dialysis treatments, Swedish Medical Center — Cherry Hill, Swedish earnings on investments and philanthropic gifts.