Opera House 1C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

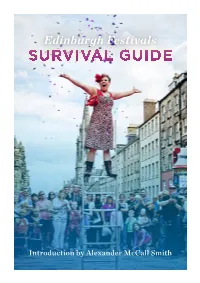

Survival Guide

Edinburgh Festivals SURVIVAL GUIDE Introduction by Alexander McCall Smith INTRODUCTION The original Edinburgh Festival was a wonderful gesture. In 1947, Britain was a dreary and difficult place to live, with the hardships and shortages of the Second World War still very much in evidence. The idea was to promote joyful celebration of the arts that would bring colour and excitement back into daily life. It worked, and the Edinburgh International Festival visitor might find a suitable festival even at the less rapidly became one of the leading arts festivals of obvious times of the year. The Scottish International the world. Edinburgh in the late summer came to be Storytelling Festival, for example, takes place in the synonymous with artistic celebration and sheer joy, shortening days of late October and early November, not just for the people of Edinburgh and Scotland, and, at what might be the coldest, darkest time of the but for everybody. year, there is the remarkable Edinburgh’s Hogmany, But then something rather interesting happened. one of the world’s biggest parties. The Hogmany The city had shown itself to be the ideal place for a celebration and the events that go with it allow many festival, and it was not long before the excitement thousands of people to see the light at the end of and enthusiasm of the International Festival began to winter’s tunnel. spill over into other artistic celebrations. There was How has this happened? At the heart of this the Fringe, the unofficial but highly popular younger is the fact that Edinburgh is, quite simply, one of sibling of the official Festival, but that was just the the most beautiful cities in the world. -

Scottish Parliament Building Edinburgh, Scotland

Scottish Parliament Building Client: Location: Edinburgh, Scotland Date: Typology: In 1998 EMBT won the bid to design the new Edinburgh Parliament building. The Architect: proposal generated great enthusiasm due to its organic capacity to combine existing Project directors: elements with new technologies through the contemporary and unique language of the Design team: Barcelona studio. The project’s development centered on reflecting the characteristics Gross floor area: of the country and its inhabitants via a new way of building that was directly linked to the land itself. This close tie to the site and its setting would, when the adjacent distillery is demolished, enable the generation of multiple perspective lines on the city. Intentionally, a contrast is sought, a conceptual distance, between the new construction and Holyrood Palace, the twelfth-century royal residence that has been renovated many times. Unlike the palace, which dominates the landscape, the new Scottish Parliament drops literally into the hillside terrain, the lowest part of Arthur’s Seat, and appears to sprout from the living stone. Client: The Scottish Executive Government Location: Edinburgh, Scotland Date: 2004 Typology: Civic Government, Landscape Architects: Enric Miralles, Benedetta Tagliabue in a joint venture with: RMJM Scotland LTD, M.A.H Duncan, T.B. Stewart EMBT Staff Competition: Joan Callis, project leader. Constanza Chara, Omer Arbel, Fabian Asunción, Steven Bacaus, Michael Eichhorn, Christopher Hitz, Francesco Mozzati. Leonardo Giovanozzi, Fergus Mc Ardle, Fernanda Hannah, Annie Marcela Henao, Ricardo Jimenez. Project: Joan Callis, project leader. Karl Unglaub, site architect Constanza Chara Umberto Viotto, Michael Eichhorn, Fabian Asunción, Fergus Mc Ardle, Sania Belli , Gustavo Silva Nicoletti, Vicenzo Franza , Antonio Benaduce, Andrew Vrana, Bernardo Ríos, Torsten Skoetz, Tomoko Sakamoko, Javier García Germán,. -

Troisième Classe Grise Brutal Glasgow- Brutal Edinburgh Fevrier 2017

Glasgow, Red Road Flats, 1969 BURNING SCOTLAND TROISIÈME CLASSE GRISE BRUTAL GLASGOW- BRUTAL EDINBURGH FEVRIER 2017 1 Gillespie Kidd & Coia, St Peter’s College, Cardross, 1959-1966 (ruins) ******************************* Barry Gasson & John Meunier with Brit Andreson, Burrell Collection, Glasgow, 1978–83 ******************************* Covell Matthews & Partners Empire House, Glasgow, 1962-1965 ******************************* 2 W. N. W. Ramsay, Queen Margaret Hall, University of Glasgow, 1960-1964 ******************************* T. P. Bennett & Son, British Linen Bank, Glasgow, 1966-1972 ******************************* 3 Wylie Shanks & Partners, Dental Hospital & School, Glasgow, 1962-1970 ******************************* W. N. W. Ramsay Dalrymple Hall, University of Glasgow, 1960-1965 ******************************* 4 Irvine Development Corporation, Irvine Centre, 1960-1976 ******************************* William Whitfield & Partners, University of Glasgow Library, 1963-1968 ******************************* Keppie Henderson & Partners, University of Glasgow - Rankine Building, 1964-1969 ******************************* 5 David Harvey Alex Scott & Associates, Adam Smith Building, University of Glasgow, 1967 ******************************* Scott Brownrigg & Turner, Grosvenor Lane Housing, Glasgow, 1972 ******************************* Keppie Henderson & Partners, Student Amenity Building, University of Glasgow, 1965 (Demolished: 2013 ?) ******************************* 6 Keppie Henderson & Partners, Henry Wood Building, Jordanhill, Glasgow, -

Foster Plans New Beijing HQ As Base for China Expansion

FRIDAY August 12 2011 Issue 1977 £2.90 Making a splash bdonline.co.uk Zaha Hadid’s Aquatics Centre may be late to the party “One would think that one was in a but arrives with a flourish P.12 subterranean city, that’s how heavy is the atmosphere, how profound is A special bond the darkness!” Eric Parry is drawn to Fritz Höger’s Hamburg brick masterpiece P.16 BUILDING DESIGN ARCHITECTS’ FAVOURITE WEEKLY INSIDE NEWS ANALYSIS Architecture Foster plans new Beijing HQ and the riots Urban planning expert Wouter Vanstiphout looks at what this week’s violence could mean as base for China expansion for UK city development. P.3 NEWS Firm’s office will neighbour Ai Weiwei gallery and promote Chinese art and architecture Alsop’s latest incarnation Ellis Woodman galleries, it will have a café. It will “There is an Bank Headquarters in Hangzhou should take the plunge. “If you are host exhibitions by young artists awareness of and a scheme designed in collab- immersed in those places instead The name of Will Alsop’s latest Foster & Partners is designing its and architects in China. It will the fragility oration with Thomas Heather- of reading about them in the press venture, with ex RMJM principal own headquarters building in have an apartment for an artist in of being overly wick for the upmarket Bund dis- you do get a very different experi- Scott Lawrie, will be registered China as the firm looks to expand residence. dependent trict of Shanghai. ence.” in the next few weeks. P.5 the amount of business it carries “It will also be a centre for our- on one place” Foster said the firm was eyeing The company’s 2011 results will out in the country. -

An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings

ctbuh.org/papers Title: An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing & Diagrid Systems Authors: Kheir Al-Kodmany, Professor, Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois Mir Ali, Professor Emeritus, School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Subjects: Architectural/Design Structural Engineering Keywords: Structural Engineering Structure Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 5 Number 4 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany; Mir Ali International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of December 2016, Vol 5, No 4, 271-291 High-Rise Buildings http://dx.doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2016.5.4.271 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php An Overview of Structural and Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing and Diagrid Systems Kheir Al-Kodmany1,† and Mir M. Ali2 1Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL 60607, USA 2School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA Abstract There is much architectural and engineering literature which discusses the virtues of exterior bracing and diagrid systems in regards to sustainability - two systems which generally reduce building materials, enhance structural performance, and decrease overall construction cost. By surveying past, present as well as possible future towers, this paper examines another attribute of these structural systems - the blend of structural functionality and aesthetics. Given the external nature of these structural systems, diagrids and exterior bracings can visually communicate the inherent structural logic of a building while also serving as a medium for artistic effect. -

Building Stones of Edinburgh's South Side

The route Building Stones of Edinburgh’s South Side This tour takes the form of a circular walk from George Square northwards along George IV Bridge to the High Street of the Old Town, returning by South Bridge and Building Stones Chambers Street and Nicolson Street. Most of the itinerary High Court 32 lies within the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. 25 33 26 31 of Edinburgh’s 27 28 The recommended route along pavements is shown in red 29 24 30 34 on the diagram overleaf. Edinburgh traffic can be very busy, 21 so TAKE CARE; cross where possible at traffic light controlled 22 South Side 23 crossings. Public toilets are located in Nicolson Square 20 19 near start and end of walk. The walk begins at NE corner of Crown Office George Square (Route Map locality 1). 18 17 16 35 14 36 Further Reading 13 15 McMillan, A A, Gillanders, R J and Fairhurst, J A. 1999 National Museum of Scotland Building Stones of Edinburgh. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Geological Society. 12 11 Lothian & Borders GeoConservation leaflets including Telfer Wall Calton Hill, and Craigleith Quarry (http://www. 9 8 Central 7 Finish Mosque edinburghgeolsoc.org/r_download.html) 10 38 37 Quartermile, formerly 6 CHAP the Royal Infirmary of Acknowledgements. 1 EL Edinburgh S T Text: Andrew McMillan and Richard Gillanders with Start . 5 contributions from David McAdam and Alex Stark. 4 2 3 LACE CLEUCH P Map adapted with permission from The Buildings of BUC Scotland: Edinburgh (Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press), by J. Gifford, C. McWilliam and D. -

Future of Entertainment Ticketing F Rum London • 19-20 March 2013 Discussion Paper 06

TICKETING TECHNOLOGY THE FUTURE OF ENTERTAINMENT TICKETING F RUM LONDON • 19-20 MARCH 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER 06 The Edinburgh Experience: A Bird’s-Eye View of Clicket.co.uk by Jo Michel, Director, Michel Consultancy The Edinburgh Portal Project was originated to unify the customer experience when searching for events and activities across the city. In this paper, I aim to give you a bird’s-eye view of the experience of those involved in the project which was finally launched in 2011 as www.Clicket.co.uk I came to Edinburgh in June 2008 to be the Ticketing Manager at Hub Tickets, the agency which is operated by the Edinburgh International Festival and sells tickets for “ ...a single point of entry for that festival and many others during the summer visitors, which would offer months each year. product from all the Edinburgh Edinburgh – why a portal? venues...” Edinburgh is a festival city. As everyone knows, it is the home of the largest of them all: the Edinburgh Festival Fringe; the prestigious Edinburgh International Festival; The Edinburgh Book Festival; Edinburgh Jazz & Blues Festival; Structure and strategy Festival of Politics; and Festival of Spirituality and Peace all of The Audience Business (TAB) was appointed as the project which run concurrently throughout August, each year. management and a Strategy Working Group put in place to Edinburgh is also home to the renowned Traverse Theatre guide the decision making process and to be representative Company, has great touring venues in the Festival Theatre of the core stakeholders in the project. The Edinburgh Portal and Edinburgh Playhouse, the beautiful Queens Hall and a Project had begun. -

Today's News - Wednesday, February 27, 2008 Sculpture + School Architecture Can Enliven the Educational Process in Unexpected Ways

Home Yesterday's News Calendar Contact Us Subscribe Advertise Today's News - Wednesday, February 27, 2008 Sculpture + school architecture can enliven the educational process in unexpected ways. -- America's 50 greenest cities (and why). -- Dyckhoff on "oligarchitects" - the "Mr. Hyde in architects" who can't resist "power, riches and gold taps." -- Heathcote on a new, "more sophisticated type of urbanism" in the midst of the Middle East's "self-conscious architectural zoo." -- Something goes awry in plans for a model green village in China. -- A Providence, RI, neighborhood moving towards a long-awaited renaissance. -- Mays is impressed with a young architect's vision for Waterfront Toronto. -- Another take on Downtown L.A.'s downturn. -- It's not all doom and gloom: Downtowners of Distinction Awards honor stand-out projects. -- A new arts center for Aberdeen, Scotland. -- Farrelly on public transportation (or lack of). -- Mid-century Modern at risk in New Orleans. -- Googie gets reprieve in Seattle. -- Aerotropolis: the city of the future. -- In pictures: Beijing's Terminal 3. -- A monument to Navajo Code Talkers takes shape. -- Edgy design is making its mark at a mall near you. -- Trompe l'oeil construction cover creates an artful installation instead of an artless mess. To subscribe to the free daily newsletter click here INSIGHT: Art in Learning: Bringing the Tradition of Sculpture in Architecture to Education: Art incorporated into school architecture can enliven the educational process in unexpected ways. By Barry Svigals, FAIA [images]- ArchNewsNow America's 50 Greenest Cities: #1: Portland, Oregon; #20: New York City; #32: Anchorage, Alaska [links]- Popular Science Build me a pyramid: Daniel Libeskind and the oligarchitects: Western architects make a killing building monuments for regimes that you wouldn't want to bring home to meet the folks...Despite being plagued with a social conscience...the Mr Hyde in architects just can't help being tempted by unlimited power, riches and gold taps. -

The Design Studio Brief in Architecture's

Charrette:essay Tales and tools: the Design Studio Brief in Architecture’s expanded field. Suzanne Ewing. Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, University of Edinburgh. ABSTRACT This essay argues that the Design Studio Brief establishes tacit disciplinary practices of architecture, as well as more explicit pursuit of topics of formulated relevance or concern. A series of tales of Design Studio Briefs from the fourth year of study at one UK Architecture School are sampled at dates which coincide with significant moments in Scotland’s recent constitutional history: the 1979 devolution Referendum, the 1997/1999 establishment of the Scottish Parliament, and the 2014 Independence Referendum. The tales are followed by a discussion on tools: towards means and practices which might inform the re-tooling of the Design Studio Brief and its ends. KEYWORDS design studio brief, disciplinary practices, architectural education Over the past forty years the field of global Higher Education economy. Allied to Architecture has expanded in scope and in the funding conditions which redefine national and potential of architectural design as subject and transnational educational responsibilities, what practice.1 Focus has shifted from site to field, educational capital is and what it is for, from static object to moving project.2 requires a refreshed ethical position.5 Preoccupations of Design Studios in architectural education have shifted from Euro- Architectural Design Studios are often known centric sites and artefacts deemed worthy -

Hidden Edinburgh Challenge

Hidden Edinburgh Challenge Created for the Senior Section Spectacular 2016 Introduction The Hidden Edinburgh Challenge is designed for Rainbows, Brownies, Guides, the Senior Section, Leaders and Trefoil members. It has been designed by Girlguiding Edinburgh’s ‘Team Spectacular’, to showcase some of Edinburgh’s hidden treasures, and to give you an opportunity to explore this beautiful city through a range of activities that can be completed in the unit meeting place, and out and about around the city. The badge accompanying this challenge is circular, with a 3-inch diameter and gold accenting. It features a unicorn, Girlguiding Edinburgh’s Senior Section Spectacular mascot. Badges cost £1 each plus P&P. This challenge has been produced to raise funds for Girlguiding Edinburgh’s Senior Section Spectacular activities, and to contribute towards further Senior Section activities following 2016. To earn the badge, Rainbows gain 60 points, Brownies 70 points, Guides 80 points, Senior Section/Leaders/Trefoil Members 100 points. You should complete at least 10 points from each of Places and Spaces, Unicorns, and Guiding. The rest of your points can come from sections of your choice. We have tried to include a range of activities to suit all ages and abilities, but please feel free to adapt any of the activities to suit participants as needed. Badges can be ordered using the order form on the last page. We hope you have fun completing this challenge and exploring our beautiful city. Please share your photos and stories with us by emailing Team Spectacular at [email protected]! Places and Spaces Edinburgh is full of weird and wonderful places. -

Chronicle February 2011

picturethis THECHRONICLE £50 voucher to be won See page 15 for FEBRUARY 2011 Issue No. 125 Free competition details INSIDE THIS ISSUE COMMUNITY IN FOCUS Carr-Gomm Scotland page 3 VOTE FOR TAMARA! BINGHAM RESIDENTS SAY Dance sensation RESPITE PLANS LEAVE in final of Sky1’s ‘Got to Dance’ THEM OUT IN THE COLD page 16 By Phil Harris January, with the suggested change. Local resident Gail Ross said: ple and community. So why move He told the Chronicle: “Going by “Let’s be honest. The children and something else in. It’s no advan- WIN TICKETS TO COUNCIL PLANS TO relocate the press statement, they [the families using Seaview aren’t tage to the people that live here. the Seaview Children’s Respite council] had been preparing this going to put any money into this It’s not right and it’s not fair.” SEE THE MAGIC Centre from Portobello to the behind closed doors but this is just community. We had promises Bingham resident and youth OF MOTOWN site of the former Lismore the start of the pre-planning con- when they came for the school but worker at the local community Primary School in Bingham, sultation. They [the council] need they never happened. centre, Margaret Paterson, added: have met with oppostition from to get the views and objections of “At the moment in Bingham we “I feel that Bingham has had a raw local residents. the locals before going to the have six care facilities. One of deal. Once upon a time we had a Concerns were raised at the expense of drawing up proper these is a homeless unit and we butcher, baker, fishmonger, post Bingham Neighbourhood plans and submitting them. -

Explore the Character of Edinburgh, Scotland (Europe) for Seven Days & Six Nights at Your Choice of the Radisson Blu Hotel

Explore the Character of Edinburgh, Scotland (Europe) for Seven Days & Six Nights at Your Choice of the Radisson Blu Hotel, The Principal Edinburgh Charlotte Square, the Macdonald Holyrood, or the Apex International Hotel with Economy Class Air for Two Escape to vibrant Edinburgh, where history and modernity meet in a cosmopolitan city set against the striking landscape of Scotland. Originally Scotland's defensive fortress for hundreds of years with its position presiding over the North Sea, Edinburgh is now a must-see destination. Visit its namesake Edinburgh Castle, home to the 12th-century St. Margaret's Chapel, and wander the cobblestone streets that lead to fantastic dining, rambunctious taverns and exciting shopping. A beautiful and cultured city, you will find a wealth of things to do in Edinburgh. Discover nearby historic attractions like the shops along Princes Street, the National Museum of Scotland or the Scotch Whisky Heritage Centre, all within walking distance of the hotels. Start your Royal Mile journey at Edinburgh Castle and take in the dramatic panorama over Scotland's capital. From there, walk down the cobbled street past the St. Giles Cathedral, John Knox's House and shops selling Scottish crafts and tartan goods. At the end of the Mile, you'll find a uniquely Scottish marriage of old and new power, where Holyrood Palace sits opposite the Scottish Parliament. After a day spent sightseeing, Edinburgh at night is not to be missed. Take in a show at the Edinburgh Playhouse, enjoy a meal at one of Edinburgh's Michelin-starred restaurants or dance the night away in the lively clubs on George Street or the Cowgate.