Can a University Campus Work As a Public Space in the Metropolis of a Developing Country? the Case of Ain-Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf (464.93 K)

Egypt. J. Agric. Res., 89 (2), 2011 535 POPULATION DYNAMICS OF THE GREEN SHIELD SCALE, PULVINARIA PSIDII (HEMIPTERA : COCCIDAE) ON GUAVA TREES AT SHIBIN EL-QANATER DISTRICT, QALUBIYA GOVERNORATE, EGYPT ELWAN, E. A., A. M. SERAG AND MAHA I. EL-SAYED Plant Protection Research Institute, ARC, Dokki, Giza (Manuscript received 5 January, 2011) Abstract The population dynamics of the green shield scale, Pulvinaria psidii (Mask.) (Hemiptera - Coccidae) was studied for two successive years (2008-2009) on guava trees at Shibin El-Qanater district, Qalubiya Governorate. The obtained results revealed that, P. psidii occurred on guava trees all the year round and has two overlapping generations a year. The 1st generation started from early March to early August/mid-August, peaked in mid-May (early summer) with duration of 5.0 - 5.5 months at field conditions of 20.7 - 21.3°C and 70.7 - 71.9%R.H. The 2nd generation occurred from early May to mid-November, peaked in mid-August (late summer) with duration of 6.0 - 6.5 months at 24.2 - 25.0°C and 69.4 - 70.4%R.H., respectively. The favorable time for abundance of P. psidii occurred in early and late summer during both high temperature and relative humidity. The adult population was relatively higher than nymphal population one in winter months and this may be due to the cold weather and most of the nymphs attained to the adult stage which sheltered on stems bark or in the stem cracks. Daily mean temperature and %R.H. were effective on both nymph and adult populations in 1st and 2nd generations in the two studied years, the population was correlated with the increase of temperature. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

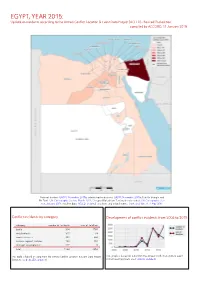

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

List of Reviewers 2018

List of Reviewers (as per the published articles) Year: 2018 Asian Journal of Research in Infectious Diseases ISSN: 2582-3221 2018 - Volume 1 [Issue 1] An Unusual Development of a Madura Foot: A Case Report DOI: 10.9734/AJRID/2018/v1i113936 (1) Ritesh Kumar Tiwari, Shri Ram Murti Smarak College of Engineering and Technology (Pharmacy), India. (2) Magda Ramadan, Department of Microbiology, Ain Shams University, Egypt. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/24704 An Interesting Case of Sphingobacterium Multivorum Neck Abscess DOI: 10.9734/AJRID/2018/v1i113941 (1) Jorge Roig, Spain. (2) Maria Antonietta Toscano, University of Catania, Italy. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/24984 Qualitative Exploration of Ebola Risk Perception among Mortuary Workers in Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria DOI: 10.9734/AJRID/2018/v1i113944 (1) Oti Baba Victor, Nasarawa State University, Nigeria. (2) Y. J. Peter, University of Abuja, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/25333 Chikungunya Virus: An Emerging Threat to South East Asia Region DOI: 10.9734/AJRID/2018/v1i113946 (1) Chan Pui Shan Julia, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong. (2) S. C. Weerasinghe, Teaching Hospital Kurunegala, Sri lanka. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/25474 Awareness about Hepatitis B and/or C Viruses among Residents of Adama and Assela Cities. Oromia Regional State, Oromia, Ethiopia DOI: 10.9734/AJRID/2018/v1i113950 (1) Itodo, Sunday Ewaoche, Niger Delta University, Nigeria. (2) Hany M. Ibrahim, Menoufia University, Egypt. (3) Oti Baba Victor, Nasarawa State University, Nigeria. (4) Wen-Ling Shih, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Taiwan. -

List of Reviewers (As Per the Published Articles) Year: 2016

List of Reviewers (as per the published articles) Year: 2016 Journal of Advances in Biology & Biotechnology ISSN: 2394-1081 2016 - Volume 5 [Issue 1] DOI : 10.9734/JABB/2016/20465 (1) Abdullah Yusuf, National Institute of Neurosciences & Hospital, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Bangladesh. (2) S. Thenmozhi, Periyar University, India. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/11900 DOI : 10.9734/JABB/2016/21996 (1) Anthony Cemaluk C. Egbuonu, Okpara University of Agriculture Umudike, Nigeria. (2) Hala Fahmy Zaki, Cairo University, Egypt. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/12122 DOI : 10.9734/JABB/2016/22523 (1) Abdullahi Hassan Kawo, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. (2) Rodrigo Crespo Mosca, Sao Paulo University, Brazil. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/12257 DOI : 10.9734/JABB/2016/20787 (1) Charu Gupta, Amity University UP, India. (2) Dorota Wojnicz, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/12258 DOI : 10.9734/JABB/2016/22047 (1) Ds Sheriff, Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Melmaruvathur, Chennai, India. (2) Bhaskar Sharma, Suresh Gyan Vihar University, Rajasthan, India. (3) Bergaoui Ridha, National Institute of Agronomy, Tunisia. (4) Mohamed Mohamed Abdel-Daim, Suez Canal University, Egypt. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/12259 DOI : 10.9734/JABB/2016/22625 (1) Ayona Jayadev, All Saints’ College, Kerala, India. (2) Sahar Mohamed Kamal Shams El Dine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. (3) Ahmed Hegazi, National Research Centre, Egypt. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/12260 2016 - Volume 5 [Issue 2] DOI : 10.9734/JABB/2016/21974 (1) Abdullahi M. -

The Data on Periodical (Weekly) Market at the End of the 19Th Century in Egypt -The Cases of Qaliubiya, Sharqiya and Daqahliya Provinces

The Data on Periodical (Weekly) Market at the End of the 19th Century in Egypt -The cases of Qaliubiya, Sharqiya and Daqahliya Provinces Hiroshi Kato Some geographers and historians are concerned with periodical market, which they define as the place of economic transactions peculiar to so called "peasant society. In Egypt, which is, as well known, a typical hydraulic society, periodical market, that is weekly market (α1- siiq al-usbu i) in the Islamic world, still has the important economic functions in rural areas at the present, as well as it had in the past. The author is now collecting the data on Egyptian weekly market from the 19th century to the present, based upon source materials on one hand, and field research on the other. The aim of this paper is to present some statistical and ge0- graphical data on Egyptian weekly market at the end of the 19th century to the researchers who are interested in periodical market in agrarian society, before the intensive study, which the author is planning in the future, on the economic functions of Egyptian weekly market and their transformation in the process of the modernization of Egyptian society. The source material from which the data are collected is A. Boinet, Geographie Econ0- mique et Administrative de I'Egypte, Basse-Egypte I, Le Caire, 1902. It is the results of the population census in 1897 and the agrarian census maybe took in 1898 and 1899, being annexed to the population census in the previous year. The data are arranged village by village, and contain the statistics on cultivated area, crops, planted trees, animals, industry, traffic by rail- road, and transportation by the Nile and canals, and the descriptive informations and remarks on school, canal, railroad, market, post office and so on. -

LIST of PARTICIPANTS GAFFI Global Fungal Infection Forum 3 April 2018 Kampala Uganda 1/3

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS GAFFI Global Fungal Infection Forum 3 April 2018 Kampala Uganda 1/3 Name Affiliation Abdu Kisekka Musubire Infectious Diseases Institute, Kampala, Uganda Afia Zafar The Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan Aida Sadikh Badiane Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal Alessandro C. Pasqualotto Santa Casa de Misericordia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil Alexander Jordan Centers for Disease Control- Mycotic Diseases Branch, Atlanta, USA Alfred Andama Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Ali Osmanov Kiev, Ukraine Amanda Mutlow F.Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Midrand, South Africa Ana Alastruey-Izquierdo Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain Andrew Kambugu Infectious Diseases Institute, Kampala, Uganda Andrew Katende Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Anyess Travers Global Health Impact Group, Atlanta, USA Arunaloke Chakrabarti Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India Bashir Lwala Medical Access, Kampala, Uganda Ben Cheng Global Health Impact Group, Atlanta, USA Caleb Skipper University of Minnesota, Minnesota, USA Chantal Migone World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland Charles Emuduko Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda Charles Kiyaga African Society for Laboratory Medcicine Charlotte Sriruttan National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa Christina Mwachari University of Maryland, Nairobi, Kenya Christine Mandengue Université des Montagnes, Bangangte, Cameroon Conrad Muzoora Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara, Uganda Couldiaty -

From the Director the Vis Moot As A

University of Pittsburgh School of Law Volume 19, Fall 2014 CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL LEGAL EDUCATION From the Director students, and we invite you to consider In December of 2013, we welcomed their stories, in their words, which are Brian Fraile ( JD ’13) to the CILE By Professor Ronald A. Brand included in this issue of CILE Notes. staff as assistant director. Brian worked Chancellor Mark A. Nordenberg On the back cover, you will note that with CILE extensively as a student, University Professor we also look forward to providing an including in Vis Moot training in online version of our LLM program Istanbul, Turkey, and Abu Dhabi, UAE, As we enter CILE’s 20th year, beginning in fall 2015. We already have and spent fall 2013 teaching at Moi we welcome another stellar group of completed much of the work for the University School of Law as part of our LLM, SJD, and JD students to our pro- online courses and are excited about partnership there. While a recent grad, he grams and look forward to celebrating the this natural extension of CILE into the brings a wealth of experience and skills completion of those 20 years in the fall of broader realm of legal education. that have already provided significant 2015. We also pause to look back, not only benefits to our students. on the past year, but on the longer term success of a number of CILE programs. The feature article that follows reviews The Vis Moot as a Platform and 15 years of CILE use of the Vis Inter- national Commercial Arbitration Moot a Process for CILE Expansion of as a platform for international legal International Legal Education education and development. -

Editorial Board Ass

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector THE EGYPTIAN JOURNAL OF RADIOLOGY & NUCLEAR MEDICINE Editor-in-Chief A.E. Mahfouz Nagui Abdelwahab T.A. El-Diasty Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Professor of Radiology, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt Urology and Nephrology Center, Y. Abdelazim Abbas H.H. Lotfy Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Professor of Radiology, Military Medical Academy, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt Cairo, Egypt F.H. Al Sheikh Honorary Editor Associate Editors/Neuroradiology Head of Neuroradiology, Riyadh Armed Forces F.A. Tantawy Hospital, Saudi Arabia Majda M. Thurnher Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Professor of Radiology, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt M. Shafik Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Medizinische Universitat Wien, Austria E. Turgut Tali Deputy Editors Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt D.A. Stringer Professor of Radiology, Gazi University School of W. Tantawy Professor of Radiology, President of Asia Oceanic Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Society of Pediatric Radiology, Singapore S. Saleem Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt M. Azouz Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, S.A. Hanna Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Professor of Radiology, Royal College of Physicians, Surgeons of Canada, Que´bec, Canada Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt Associate Editors/Oncology H. Rigertz K.M. Elsayes I. Zaky Visiting Professor, Lucile Packard ChildrenÕs Assistant Professor of Radiology, MD Anderson Professor of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hospital, Stanford Department of Radiology, Cancer Center, University of Texas, Houston, National Cancer Institute, Cairo University, Stanford University, California, USA Texas, USA Cairo, Egypt N. -

3.Safwat A. Azer, Fatma S. Mohammad

Human Journals Research Article August 2019 Vol.:13, Issue:2 © All rights are reserved by Safwat A. Azer et al. Survey and Evaluation of the Weeds Associated with Winter Crops at Some Areas of Qalyubia Governorate, Egypt Keywords: Survey, Evaluation, Weeds, Winter Crops, Qalyubia governorate, Egypt ABSTRACT 1*Safwat A. Azer, 1Fatma S. Mohammad This research aims to survey and evaluate the weeds associated with winter crops at some areas of Qalyubia 1. Flora and Phytotaxonomy Researches Department, governorate. Two hundred and eighty six quadrates were selected to represent the distribution of weed species among Horticultural Research the studied crops and areas. At Al Gabal Al Asfar area, the Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. highest frequency ratio 55% of Cyperus rotundus was recorded while; the lowest 2.5 % was noticed for Leucaena Submission: 28 July 2019 leucocephala, Sesbania sesban and Solanum tuberosum. Similarly, the ratio 2.5 % was observed for Brassica nigra, Accepted: 2 August 2019 Desmostachya bipinnata, Medicago polymorpha and Rumex Published: 30 August 2019 dentatus at Abu Zaable area. The highest abundance ratio 38% of dominant weed species were recorded at Shibin El Qanater while; the lowest 4.76% was noticed at Qalyub area. Based on similarity values of weed species among the studied areas, Al Khankah and Al Gabal Al Asfar showed the highest value 0.700 while; the lowest 0.373 was noticed between Qaha and Al Gabal Al Asfar. Moreover, the similarity values www.ijsrm.humanjournals.com of weed species among studied crops showed that Egyptian clover and lettuce had the highest value 0.646 while; the lowest 0.167 was recorded between cauliflower and strawberry. -

LOT NUMBER RESERVE £ Postal History 1 Early Missionary Letter

1 LOT NUMBER RESERVE £ Postal history 1 Early Missionary letter dated 7 Dec 1830, Alexandria to Beyroot 59.00 2 French Consular Mail – Entire Alex to Marseilles with 40 centimes cancelled 5080 (diamond) via Paquebots de la Mediterrane (in red) and PD (in red). Reduced rate from 1866 44.00 Second Issue, 1867-69 (Nile Post numbers) 3 5-para (D8), Types 104 unused, with photograph 24.00 4 10-para (D91), used with watermark on face. ESC certificate 45.00 5 3 x 10-para (D9a, 9b, 9c), used in excellent condition with photograph 85.00 6 10-para (D9, Types 1-4), unused, includes Stone A Type 2 (D9A) 83.00 7 10-para (D9f, Types 1-4), unused, includes Stone B Type 2 unbroken O, with photograph 63.00 8 10-para (D9 Types 1-4), unused and used including Stone A 3rd State Type 2 with photograph 111.00 9 20-para (D10 Types 1-4), unused Stone A (2 dots) with photograph 72.00 10 20-para (D10i Types 1-4), unused Stone B (3 dots) with photograph 65.00 11 1-piastre (D11), 37 copies unused and used, all types. Worthy of research by a student of this issue 49.00 12 5-piastre (D 13 Types 1-4), unused, fine condition 390.00 13 5-piastre (D13 Types 1-4), used, fine condition 240.00 14 5-para (D8k) used, misplaced perforation 43.00 15 5-para (D8), yellow green, mint, very fine 19.00 16 10-para (D9j), unused, “white hole in wig” variety 29.00 17 1-piastre (D11v), unused, “inverted watermark” 19.00 18 1-piastre (D11m), unused, imperforate 22.00 Postage Due issue 1922 (Nile Post numbers) 19 PD30a, mint block of 12, overprint à cheval 186.00 20 PD30a, three mint singles, -

Empowering Healthcare Professionals to Diagnose, Manage, and Prevent Liver Diseasesto the Benefit of Patients in Africa

COLDA 2020 VIRTUAL CONFERENCE ON LIVER DISEASE IN AFRICA 10 - 12 SEPTEMBER 2020 PROGRAM CHAIRS Papa Saliou Mbaye MD Société Sénégalaise de Gastroentérologie et d’Hépatologie Senegal Manal El-Sayed MD, PhD Ain Shams University Egypt Charles Boucher MD, PhD Erasmus Medical Center ABOUT THE VIRTUAL CONFERENCE The Netherlands COLDA is a highly educational and prevent liver diseases for the benefit of scientific virtual conference focused patients in Africa. Delegates will be able Mark Nelson on liver disease in Africa. Considering to experience a dynamic and interactive MD, FRCP the COVID-19 situation, the educational virtual meeting. Imperial College program will be delivered in a safe and United Kingdom convenient manner without posing any We are offering delegates a special reduced risk to participants’ nor public health, and fee to participate in this online program. avoiding travel and other restrictions. By bringing together international and The conference will cover, among others: regional experts, the virtual conference • Introduction to Viral Hepatitis and • HCC and its Management will encourage the exchange of the latest Liver Disease • Challenges of integration of services research and treatments among all • Political Support & Public Health • NASH/NAFLD Management in Africa those working on liver disease in Africa. involvement • Discussion on region specific Ultimately, empowering healthcare • Management of Viral Hepatitis guidelines professionals to diagnose, manage, and The program will include materials in both English and