THE KINSHIP TERMINOLOGY of the BANNOCK INDIANS by ROBERT H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California Suzanna Theresa Montague B.A., Colorado College, Colorado Springs, 1982 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California A Thesis by Suzanna Theresa Montague Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Mark E. Basgall, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader David W. Zeanah, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date ii Student: Suzanna Theresa Montague I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, ___________________ Michael Delacorte, Ph.D, Graduate Coordinator Date Department of Anthropology iii Abstract of High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California by Suzanna Theresa Montague The study investigated pre-contact land use on the western slope of California’s central Sierra Nevada, within the subalpine and alpine zones of the Tuolumne River watershed, Yosemite National Park. Relying on existing data for 373 archaeological sites and minimal surface materials collected for this project, examination of site constituents and their presumed functions in light of geography and chronology indicated two distinctive archaeological patterns. First, limited-use sites—lithic scatters thought to represent hunting, travel, or obsidian procurement activities—were most prevalent in pre- 1500 B.P. contexts. Second, intensive-use sites, containing features and artifacts believed to represent a broader range of activities, were most prevalent in post-1500 B.P. -

Student Magazine Historic Photograph of Siletz Feather Dancers in Newport for the 4Th of July Celebration in the Early 1900S

STUDENT MAGAZINE Historic photograph of Siletz Feather dancers in Newport for the 4th of July celebration in the early 1900s. For more information, see page 11. (Photo courtesy of the CT of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw). The Oregon Historical Society thanks contributing tradition bearers and members of the Nine Federally Recognized Tribes for sharing their wisdom and preserving their traditional lifeways. Text by: Lisa J. Watt, Seneca Tribal Member Carol Spellman, Oregon Historical Society Allegra Gordon, intern Paul Rush, intern Juliane Schudek, intern Edited by: Eliza Canty-Jones Lisa J. Watt Marsha Matthews Tribal Consultants: Theresa Peck, Burns Paiute Tribe David Petrie, Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians Angella McCallister, Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community Deni Hockema, Coquille Tribe, Robert Kentta, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Susan Sheoships, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Museum at Tamástslikt Cultural Institute Myra Johnson, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation Louis La Chance, Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians Perry Chocktoot, The Klamath Tribes Photographs provided by: The Nine Federally Recognized Tribes Oregon Council for the Humanities, Cara Unger-Gutierrez and staff Oregon Historical Society Illustration use of the Plateau Seasonal Round provided by Lynn Kitagawa Graphic Design: Bryan Potter Design Cover art by Bryan Potter Produced by the Oregon Historical Society 1200 SW Park Avenue, Portland, OR 97205 Copyright -

Phonetic Description of a Three-Way Stop Contrast in Northern Paiute

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2010) Phonetic description of a three-way stop contrast in Northern Paiute Reiko Kataoka Abstract This paper presents the phonetic description of a three-way phonemic contrast in the medial stops (lenis, fortis, and voiced fortis stops) of a southern dialect of Northern Paiute. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of VOT, closure duration, and voice quality was performed on field recordings of a female speaker from the 1950s. The findings include that: 1) voiced fortis stops are realized phonetically as voiceless unaspirated stops; 2) the difference between fortis and voiced fortis and between voiced fortis and lenis in terms of VOT is subtle; 3) consonantal duration is a robust acoustic characteristic differentiating the three classes of stops; 4) lenis stops are characterized by a smooth VC transition, while fortis stops often exhibit aspiration at the VC juncture, and voiced fortis stops exhibit occasional glottalization at the VC juncture. These findings suggest that the three-way contrast is realized by combination of multiple phonetic properties, particularly the properties that occur at the vowel-consonant boundary rather than the consonantal release. 1. Introduction Northern Paiute (NP) belongs to the Western Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family and is divided into two main dialect groups: the northern group, Oregon Northern Paiute, and the southern group, Nevada Northern Paiute (Nichols 1974:4). Some of the southern dialects of Nevada Northern Paiute, known as Southern Nevada Northern Paiute (SNNP) (Nichols 1974), have a unique three-way contrast in the medial obstruent: ‗fortis‘, ‗lenis‘, and what has been called by Numic specialists the ‗voiced fortis‘ series. -

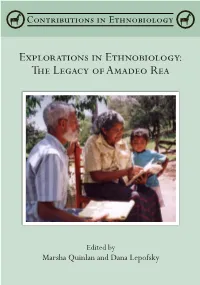

Explorations in Ethnobiology: the Legacy of Amadeo Rea

Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Copyright 2013 ISBN-10: 0988733013 ISBN-13: 978-0-9887330-1-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956081 Society of Ethnobiology Department of Geography University of North Texas 1155 Union Circle #305279 Denton, TX 76203-5017 Cover photo: Amadeo Rea discussing bird taxonomy with Mountain Pima Griselda Coronado Galaviz of El Encinal, Sonora, Mexico, July 2001. Photograph by Dr. Robert L. Nagell, used with permission. Contents Preface to Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea . i Dana Lepofsky and Marsha Quinlan 1 . Diversity and its Destruction: Comments on the Chapters . .1 Amadeo M. Rea 2 . Amadeo M . Rea and Ethnobiology in Arizona: Biography of Influences and Early Contributions of a Pioneering Ethnobiologist . .11 R. Roy Johnson and Kenneth J. Kingsley 3 . Ten Principles of Ethnobiology: An Interview with Amadeo Rea . .44 Dana Lepofsky and Kevin Feeney 4 . What Shapes Cognition? Traditional Sciences and Modern International Science . .60 E.N. Anderson 5 . Pre-Columbian Agaves: Living Plants Linking an Ancient Past in Arizona . .101 Wendy C. Hodgson 6 . The Paleobiolinguistics of Domesticated Squash (Cucurbita spp .) . .132 Cecil H. Brown, Eike Luedeling, Søren Wichmann, and Patience Epps 7 . The Wild, the Domesticated, and the Coyote-Tainted: The Trickster and the Tricked in Hunter-Gatherer versus Farmer Folklore . .162 Gary Paul Nabhan 8 . “Dog” as Life-Form . .178 Eugene S. Hunn 9 . The Kasaga’yu: An Ethno-Ornithology of the Cattail-Eater Northern Paiute People of Western Nevada . -

Northern Paiute of California, Idaho, Nevada and Oregon

טקוּפה http://family.lametayel.co.il/%D7%9E%D7%A1%D7%9F+%D7%A4%D7%A8%D7%A0%D7 %A1%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%A7%D7%95+%D7%9C%D7%9C%D7%90%D7%A1+%D7%9 5%D7%92%D7%90%D7%A1 تاكوبا Τακόπα The self-sacrifice on the tree came to them from a white-bearded god who visited them 2,000 years ago. He is called different names by different tribes: Tah-comah, Kate-Zahi, Tacopa, Nana-bush, Naapi, Kul-kul, Deganaweda, Ee-see-cotl, Hurukan, Waicomah, and Itzamatul. Some of these names can be translated to: the Pale Prophet, the bearded god, the Healer, the Lord of Water and Wind, and so forth. http://www.spiritualjourneys.com/article/diary-entry-a-gift-from-an-indian-spirit/ Chief Tecopa - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_Tecopa Chief Tecopa From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chief Tecopa (c.1815–1904) was a Native American leader, his name means wildcat. [1] Chief Tecopa was a leader of the Southern Nevada tribe of the Paiute in the Ash Meadows and Pahrump areas. In the 1840s Tecopa and his warriors engaged the expedition of Kit Carson and John C. Fremont in a three-day battle at Resting Springs.[2] Later on in life Tecopa tried to maintain peaceful relations with the white settlers to the region and was known as a peacemaker. [3] Tecopa usually wore a bright red band suit with gold braid and a silk top hat. Whenever these clothes wore out they were replaced by the local white miners out of gratitude for Tecopa's help in maintaining peaceful relations with the Paiute. -

Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 370 605 IR 055 088 AUTHOR Brandt, Randal S.; Davis-Kimball, Jeannine TITLE Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography. INSTITUTION California State Library, Sacramento.; California Univ., Berkeley. California Indian Library Collections. St'ONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. Office of Library Programs. REPORT NO ISBN-0-929722-78-7 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 251p.; For related documents, see ED 368 353-355 and IR 055 086-087. AVAILABLE FROMCalifornia State Library Foundation, 1225 8th Street, Suite 345, Sacramento, CA 95814 (softcover, ISBN-0-929722-79-5: $35 per volume, $95 for set of 3 volumes; hardcover, ISBN-0-929722-78-7: $140 for set of 3 volumes). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian History; *American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; Films; *Library Collections; Maps; Photographs; Public Libraries; *Resource Materials; State Libraries; State Programs IDENTIFIERS *California; Unpublished Materials ABSTRACT This document is the third of a three-volume set made up of bibliographic citations to published texts, unpublished manuscripts, photographs, sound recordings, motion pictures, and maps concerning Native American tribal groups that inhabit, or have traditionally inhabited, northern and central California. This volume comprises the general bibliography, which contains over 3,600 entries encompassing all materials in the tribal bibliographies which make up the first two volumes, materials not specific to any one tribal group, and supplemental materials concerning southern California native peoples. (MES) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S. -

Santa Barbara Papers in Linguistics

Santa Barbara Papers in Linguistics Proceedings from the first Workshop on American Indigenous Languages May 9-10, 1998 Department of Linguistics University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Papers in Linguistics Linguistics Department University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California 93106 U.S.A. Checks in U.S. dollars should be made out to UC Regents with $5.00 added for overseas postage. If your institution is interested in an exchange agreement, please write the above address for information. Volume I: Korean: Papers and Discourse Date $13.00 Volume 2: Discourse and Grammar $10.00 Volume 3: Asian Discourse and Grammar $10.00 Volume 4: Discourse Transcription $15.00 Volume 5: East Asian Linguistics $15.00 Volume 6: Aspects of Nepali Grammar $15.00 Volume 7: Prosody. Grammar, and Discourse in Central Alaskan Yup'ik $15.00 Proceedings from the first $20.00 Workshop on American Indigenous Languages Proceedings from the second $15.00 Workshop on American Indigenous Languages Proceedings from the third $15.00 Workshop on American Indigenous Languages CONTENTS FOREWARD............. .. 1 PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON TONE IN COATLAN-LoXICHA ZAPOTEC. 3 Rosemary G. Beam de Azcona ELIDING THE OBVIOUS: ZERO SUBJECTS IN LUSHOOTSEED . 15 David Beck LANGUAGE REACQUISITION IN A CHEROKEE SEMI-SPEAKER: EVIDENCE FROM CLAUSE CONSTRUCTION. 30 Anna Berge VERBAL ARTISTRY IN A SENECA FOLKTALE. 42 Wallace Chafe SOME OUTCOMES OFTHE GRAMMATICALIZATION OFTHE VERB ..2'00' IN APINAJE. 57 Christiane Cunha de Oliveira THE DOUBLE LiFE OF HALKOMELEM REFLEXIVE SUFFIXES. 70 Donna B. Gerdts LOCATION AND DIRECTION IN MOCOVI. 84 Veronica Grondona NOTES ON SWITCH-REFERENCE IN CREEK. -

The Tule Duck Decoy

AN FOLKLIFE STUDIES • NUMBER 6 E 99 P2F68 1990X NMAI Tule Technology Northern Paiute Uses of Marsh Resources in Western Nevada Catherine S. Fowler SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was ex pressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowl edge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale mono graphs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Anthropological Records 2: 3

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS 2: 3 THE NORTHERN PAIUTE BANDS i BY OMER C. STEWART UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 1939 THE NORTHERN PAIUTE BANDS BY OMER C. STEWART ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Vol. 2 No. 3 ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS EDITORS: A. L. KROEBER, R. H. LowIE, R. L. OLSON Volume 2, No. 3, PP. 127-149, I map Transmitted November i8, 1937 Issued March 24, 1939 Price 25 cents UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON, ENGLAND The University of California publications dealing with anthro- pological subjects are now issued in two series. The series in American Archaeology and Ethnology, which was established in 1903, continues unchanged in format, but is restricted to papers in which the interpretative element outweighs the factual or which otherwise are of general interest. The new series, known as Anthropological Records, is issued in photolithography in a larger size. It consists of monographs which are documentary, of record nature, or devoted to the presen- tation primarily of new data. MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 'CONTENTS Page Introduction. 127 The Northern Paiute .................................... 128 The bands and their chiefs. 131 Conclusion ....... 144 Bibliography. 148 TABLE 1. Summary list of Northern Paiute bands ............... ........ 146 MAP 1. Northern Paiute bands . ... frontispiece [iii] 46 C, UMATILL _0 HUNIPU A L le 44 OA. LIJ z *au 801 0 % HA LAKE M)UNTAIN VER I OME 0 SILVER MER AKE KLAMATH 00 L. ABER KLA AE TSOSC 0 MI ODO IDU 42 V F- GOOSE,--- 9 Ow 71 L. L. 13 ACH M a TV, KAM6 Su4XVII-4 KUR. -

The Burns Day School: Government Intervention and Northern Paiute Sovereignty

THE BURNS DAY SCHOOL: GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION AND NORTHERN PAIUTE SOVEREIGNTY by MADELEINE PEARA A THESIS Presented to the Department of Spanish and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts November 17, 2017 An Abstract of the Thesis of Madeleine Peara for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Spanish to be taken December, 2017 Title: The Burns Day School: Government Intervention and Northern Paiute Sovereignty Approved: _______________________________________ Jennifer O’Neal and Kevin Hatfield In 1887, a group of Northern Paiutes from the Wada-Tika band returned to Burns, Oregon following years of genocidal wars, imprisonment, and the loss of the Malheur Reservation. The dissolution of the Malheur Reservation caused the government to consider the Burns Paiutes “landless,” and therefore ineligible for federal assistance. However, in the early 1920s at the behest of the Burns Paiute community, Catholic priest Peter Heuel began to petition the government for greater assistance to the community. After many years of the government sending Burns Paiute children to schools hundreds of miles away, Burns Paiute families pushed for an educational option close to home. After the Burns School Board refused to enroll Burns Paiute children in the public school, a temporary day school for Burns Paiute children was proposed and eventually opened in 1928. This paper tracks the history of the Burns Day School in Burns, Oregon from its proposed founding in 1918 until its closure in 1948, and examines the social and economic context surrounding its creation and use. More specifically, this paper investigates the goals of the Burns Paiute community, the federal government, and the ii Burns community at large in founding the school, the extent to which the Burns Day School fell within the trend of colonial education, and the ways in which Burns Paiute families exercised tribal agency surrounding the creation of the school. -

A BIBLIOGRAPHY of the UTO-AZTECAN LANGUAGES. By- GRIMES, J

REPORT RESUMES ED 011 662 AL 000 438 A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE UTO-AZTECAN LANGUAGES. By- GRIMES, J. LARRY PUB DATE 29 MAR 66 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.09HC-$1.60 40P. DESCRIPTORS- *BIBLIOGRAPHIES, *LANGUAGES, *LINGUISTICS, *AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES, *UTO AZTECAN LANGUAGES, LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION, CONTRASTIVE LINGUISTICS, PHONOLOGY, MORPHOLOGY (LANGUAGES), ETYMOLOGY, TEXBOOKS, SONORAN, SHOSHONE, AZTECAN, HOPI, TEWA, COCA, NAHUATIL, AUSTIN THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY, CONSISTING PRINCIPALLY OF WORKS PRINTED IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH, INCLUDES DOCUMENTS FROM AS EARLY AS 1732 AND UP TO 1965. GENERAL SECTIONS COVER CLASSIFICATION, COMPARATIVE WORKS, BIBLIOGRAPHIES, AND GENERAL WORKS. MORE SPECIFIC SECTIONS DEAL WITH VARIOUS ASPECTS OF THE SONORAN, SHOSHONE, AND AZTECAN FAMILIES, AND THOSE LANGUAGES (HOPI, TEWA, AND COCA) FOR WHICH THE PRECISE CLASSIFICATION IS UNDETERMINED. (NC) W4 .c> .c) A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE UTO-AZTECAN LANGUAGES r CJ Lu Prepared for Dr, Rudolph Troike American Indian Languages U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION &WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLYAS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENTOFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION 9 POSITION OR, POLICY. Larry Grimes University of Texas March 29, 1966 AL000438 ABBREVIATIONS A Anales AA American Anthropologist, ALT Anthropological Linguistics Am.Antig, American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal AMNAHE Anales de Museo Nacional de Azoueologiat Historia, y Etnografia. Mexico. APS American Philosophical Society Boletin BAE Bulletin of American Ethnograthy. CA Current Anthropology. FBC Ms in the Franz Boas Collection of the American Pilo sophical Sociaty Library, Philadelphia* ICA international Congress of Americaniats. Investigaciones Linguisticas. NAL International Journal of American Linguistio40 INAH 411stituto Nacional de Antkopo/ogia e Historla.WAI000 OPAL Indians University Publicetions in Anthropologyand Linguistics, JAFL Journal of American Folklore* Jat, journal de la Societe deu Americanistes, Lg, Lanmmce. -

California Culture Provinces

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/californiaculturOOkroerich CALIFORNIA CULTURE PROVINCES BY A. L. KROEBER University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 151-169 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY . UNIVEESITY OF CALIFOENIA PUBLICATIONS DEPAETMENT OP ANTHBOPOLOGT publications dealing with archaeological and ethnological subjects Issued under««^?^t/°!J?'^fthe direction of the Department of Anthropology are sent in exchange for the pubU- catlons of anthropological departments and museums, and for journals devoted to general Mithropology or to archaeology and ethnology. They are for sale at the prices stated Exchanges should be directed to The Exchange Department, University Library, Berkeley, OaUfomia, U. S. A. All orders and remittances should be addressed to the University of Cailiomla Press. AMEEIOAN AECHAEOLOGT AND ETHNOLOGT.—A. L. Kroeber, Editor. Volume Prices. 1, $4.25; Volumes 2 to 11, inclusive, $3.50 each; Volume 12 and following $5.00 each. ' Cited as Univ. CaUf. PubL Am. Arch. Ethn. Price Vol.1. 1. Life and Culture of the Hupa, by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 1-88; plates*^ 1-30. September, 1903 -i 2B 2. Hupa Texts, by Pliny ~ Earle Goddard. Pp. 89-S68."''Marc£'r904 "" s"oo Index, pp. 369-378. Vol. 2. 1. The Exploration of the Potter Creek Cave, by William J. Sinclairi»^. Pdr». 1-27-l ^, plates 1-14. April, 1904 ...„ .„_ , ^ 2. The Languages of the Coast of California South of San Fr^clwo by aT I." Kroeber. Pp. 29-80, -with a map. ' June, 1904 „ .60 3.