2019 Survey of Licensed Child Care Spaces and Policies in Metro Vancouver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

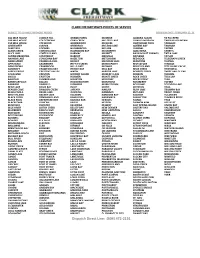

Points of Service

CLARK FREIGHTWAYS POINTS OF SERVICE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE REVISION DATE: FEBRUARY 12, 21 100 MILE HOUSE COBBLE HILL GRAND FORKS MCBRIDE QUADRA ISLAND TA TA CREEK 108 MILE HOUSE COLDSTREAM GRAY CREEK MCLEESE LAKE QUALICUM BEACH TABOUR MOUNTAIN 150 MILE HOUSE COLWOOD GREENWOOD MCGUIRE QUATHIASKI COVE TADANAC AINSWORTH COMOX GRINDROD MCLEOD LAKE QUEENS BAY TAGHUM ALERT BAY COOMBS HAGENSBORG MCLURE QUESNEL TAPPEN ALEXIS CREEK CORDOVA BAY HALFMOON BAY MCMURPHY QUILCHENA TARRY'S ALICE LAKE CORTES ISLAND HARMAC MERRITT RADIUM HOT SPRINGS TATLA LAKE ALPINE MEADOWS COURTENAY HARROP MERVILLE RAYLEIGH TAYLOR ANAHIM LAKE COWICHAN BAY HAZELTON METCHOSIN RED ROCK TELEGRAPH CREEK ANGELMONT CRAIGELLA CHIE HEDLEY MEZIADIN LAKE REDSTONE TELKWA APPLEDALE CRANBERRY HEFFLEY CREEK MIDDLEPOINT REVELSTOKE TERRACE ARMSTRONG CRANBROOK HELLS GATE MIDWAY RIDLEY ISLAND TETE JAUNE CACHE ASHCROFT CRAWFORD BAY HERIOT BAY MILL BAY RISKE CREEK THORNHILL ASPEN GROVE CRESCENT VALLEY HIXON MIRROR LAKE ROBERTS CREEK THREE VALLEY GAP ATHALMER CRESTON HORNBY ISLAND MOBERLY LAKE ROBSON THRUMS AVOLA CROFTON HOSMER MONTE CREEK ROCK CREEK TILLICUM BALFOUR CUMBERLAND HOUSTON MONTNEY ROCKY POINT TLELL BARNHARTVALE DALLAS HUDSONS HOPE MONTROSE ROSEBERRY TOFINO BARRIERE DARFIELD IVERMERE MORICETOWN ROSSLAND TOTOGGA LAKE BEAR LAKE DAVIS BAY ISKUT MOYIE ROYSTON TRAIL BEAVER COVE DAWSON CREEK JAFFARY NAKUSP RUBY LAKE TRIUMPH BAY BELLA COOLA DEASE LAKE JUSKATLA NANAIMO RUTLAND TROUT CREEK BIRCH ISLAND DECKER LAKE KALEDEN NANOOSE BAY SAANICH TULAMEEN BLACK CREEK DENMAN ISLAND -

Regular Meeting of the Council Agenda

Regular Council Meeting - April 16, 2019 - Page 1 of 104 REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE VILLAGE OF LIONS BAY HELD ON TUESDAY, APRIL 16, 2019 at 7:00 PM COUNCIL CHAMBERS, 400 CENTRE ROAD, LIONS BAY AGENDA 1. Call to Order 2. Adoption of Agenda 3. Public Participation (2 minutes per person totalling 10 minutes maximum) 4. Public Delegation Requests Accepted by Agenda Deadline (10 minutes maximum) 5. Review & Approval of Minutes of Prior Meetings A. Special Council Meeting – January 4, 2019 (Page 5) THAT the Special Council Meeting Minutes of January 4, 2019 be approved as circulated. B. Regular Council Meeting – April 2, 2019 (Page 7) THAT the Regular Council Meeting Minutes of April 2, 2019 be approved as circulated. 6. Business Arising from the Minutes 7. Unfinished Business A. Follow-Up Action Items from Previous Meetings # Meeting Date Description of Action Item Person Responsible 76 March 19, 2019 Staff to consider the creation of a policy for CAO DeJong the Infrastructure Committee and report back to Council. 77 March 19, 2019 G1: Legislative Assembly of BC – CAO CAO DeJong DeJong to respond advising that accessibility standards will be investigated when the Building Bylaw is reviewed 78 March 19, 2019 R1: Don Shaw – Train Whistle – CAO DeJong CAO DeJong to respond advising that whistling cessation applications are very involved and require costly processes which the Municipality is Regular Council Meeting - April 16, 2019 - Page 2 of 104 Agenda – Regular Meeting of Council – April 16, 2019 Village of Lions Bay Page 2 of 4 not presently in a position to pursue. -

Clark Freightways Service Schedule and Points of Service

CLARK FREIGHTWAYS SERVICE SCHEDULE AND POINTS OF SERVICE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE REVISION DATE: JULY 14, 21 DESTINATION BRANCH SHIPPING DAYS DESTINATION BRANCH SHIPPING DAYS 100 MILE HOUSE 100 MILE HOUSE M, W, F BOUCHIE LAKE PRINCE GEORGE 108 MILE HOUSE 100 MILE HOUSE M, W, F BOWSER CAMPBELL RIVER DAILY 150 MILE HOUSE WILLIAMS LAKE M, W, F BRACKENDALE SQUAMISH DAILY 70 MILE HOUSE 100 MILE HOUSE BRALORNE KAMLOOPS T, TH AHOUSAT NANAIMO BRENTWOOD BAY VICTORIA DAILY AINSWORTH CASTLEGAR M, W, F BRIDESVILLE CASTLEGAR AIYANISH TERRACE BRIDGE LAKE 100 MILE HOUSE ALERT BAY CAMPBELL RIVER M, W, F BRITANNIA BEACH SQUAMISH DAILY ALEXIS CREEK WILLIAMS LAKE TUESDAY BRILLIANT CASTLEGAR DAILY ALICE LAKE SQUAMISH DAILY BROOKMERE KAMLOOPS ALKALI LAKE WILLIAMS LAKE BROOKS BAY CAMPBELL RIVER ALLISON CREEK PRINCETON BUCKLEY BAY CAMPBELL RIVER DAILY ALPINE MEADOWS SQUAMISH DAILY BUFFALO CREEK 100 MILE HOUSE ANAHIM LAKE WILLIAMS LAKE TUESDAY BULL RIVER CRANBROOK M, T, W ANGELMONT KAMLOOPS WEDNESDAY BURNS LAKE BURNS LAKE M, T, W, F APEX MINE SITE PENTICTON BURTON VERNON M, W, F APEX MOUNTAIN PENTICTON BUTTLE LAKE CAMPBELL RIVER APPLEDALE CASTLEGAR TH, F CACHE CREEK * CACHE CREEK M, W, TH, F APPLEGROVE VERNON CALL INLET CAMPBELL RIVER AGRENTA CASTLEGAR CAMPBELL RIVER CAMPBELL RIVER DAILY ARMSTRONG VERNON DAILY CANAL FLATS * CRANBROOK M, T, W ASHCROFT * CACHE CREEK M, W, TH, F CANIM LAKE 100 MILE HOUSE W ASPEN GROVE KAMLOOPS M, W, F CANOE KAMLOOPS M, W, F ASPEN PARK KAMLOOPS CANYON CRESTON M, T, W ATHALMER CRANBROOK M, T, W CANYON CITY TERRACE AVOLA KAMLOOPS -

Smoke and Vape-Free Outdoor Public Places: BC's Municipal Momentum

Smoke and vape-free outdoor public places: BC’s municipal momentum Clean Air Coalition Knowledge Exchange, December 6, 2016 Megan Klitch Health Promotion Coordinator & Tobacco Control Lead Canadian Cancer Society, BC and Yukon Ornell Douglas, MPH Project Manager Propel Centre for Population Health Impact Overview • The case for smoke and vape-free outdoor public places • BC’s tobacco bylaw landscape • Municipal endorsement for provincial legislation • Tools for municipalities • Survey findings: from BC’s jurisdictions with tobacco bylaws Founded by: Smoking Rates by BC Health Authority 30.0% 25.0% 20.0% Northern Canada Vancouver Island 15.0% Interior BC 10.0% Fraser Vancouver Coastal 5.0% 0.0% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Source: 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey Smoke and vape-free places: 1. Protect from second-hand smoke There is no safe level of exposure to second-hand smoke Picture source: City of Kimberley website Smoke and vape-free places: 2. Positive Role Modelling 31% of BC youth (grade 10-12) have tried cigarettes 27% of Canadian youth (grade 10-12) have tried e- cigarettes Source: CSTADS 2014/15 Picture source: City of Kimberley website Smoke and vape-free places: 3. Motivation to Quit Smoking Smoke and vape-free places: 4. Positive Environmental Impact Cigarettes butts the most littered item in BC Source: 2015 Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup Recommended bylaws Prohibit smoking and vaping: • on bar and restaurant patios • on all city-managed properties, including: parks, playgrounds, trails, plazas, beaches, playing fields, recreation facilities and venues • within a buffer zone of at least 7.5 metres (best practice 9 metres) of the above mentioned and doors, windows and air intakes of public buildings cancer.ca Tobacco-bylaw protection 1. -

AT a GLANCE 2021 Metro Vancouver Committees

AT A GLANCE 2021 Metro Vancouver Committees 19.1. Climate Action Electoral Area Carr, Adriane (C) – Vancouver McCutcheon, Jen (C) – Electoral Area A Dhaliwal, Sav (VC) – Burnaby Hocking, David (VC) – Bowen Island Arnason, Petrina – Langley Township Clark, Carolina – Belcarra Baird, Ken – Tsawwassen De Genova, Melissa – Vancouver Dupont, Laura – Port Coquitlam Long, Bob – Langley Township Hocking, David – Bowen Island Mandewo, Trish – Coquitlam Kruger, Dylan – Delta McLaughlin, Ron – Lions Bay McCutcheon, Jen – Electoral Area A Puchmayr, Chuck – New Westminster McIlroy, Jessica – North Vancouver City Wang, James – Burnaby McLaughlin, Ron – Lions Bay Patton, Allison – Surrey Royer, Zoe – Port Moody Finance and Intergovernment Steves, Harold – Richmond Buchanan, Linda (C) – North Vancouver City Yousef, Ahmed – Maple Ridge Dhaliwal, Sav (VC) – Burnaby Booth, Mary–Ann – West Vancouver Brodie, Malcolm – Richmond COVID–19 Response & Recovery Task Force Coté, Jonathan – New Westminster Dhaliwal, Sav (C) – Burnaby Froese, Jack – Langley Township Buchanan, Linda (VC) – North Vancouver City Hurley, Mike – Burnaby Baird, Ken – Tsawwassen First Nation McCallum, Doug – Surrey Booth, Mary–Ann – West Vancouver McCutcheon, Jen – Electoral Area A Brodie, Malcolm – Richmond McEwen, John – Anmore Clark, Carolina – Belcarra Stewart, Kennedy – Vancouver Coté, Jonathan – New Westminster Stewart, Richard – Coquitlam Dingwall, Bill – Pitt Meadows West, Brad – Port Coquitlam Froese, Jack – Langley Township Harvie, George – Delta Hocking, David – Bowen Island George -

Regular Meeting of the Council Agenda

VoLB Regular Council Meeting - July 21, 2015 - Page 1 of 152 REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE VILLAGE OF LIONS BAY HELD ON TUESDAY, JULY 21, 2015 at 7:00 PM COUNCIL CHAMBERS, 400 CENTRE ROAD, LIONS BAY AGENDA 1. Call to Order 2. Approval of Agenda 3. Public Participation 4. Delegations A. Mr. John Povill & Ms. Anna Torrance Delegation Request (Page 3) 5. Adoption of Minutes A. July 7, 2015 – Regular Council Meeting (Page 5) B. July 14, 2015 – Special Council Meeting (Page 11) 6. Business Arising from the Minutes A. Action Items Report (Page 13) 7. Unfinished Business 8. Reports A. Chief Administrative Officer B. Mayor and Council C. Committees D. Staff i. Public Works Manager (Page 15) E. Emergency Services Reports (Page 19) 9. Resolutions 10. Bylaws A. Council Procedures Bylaw No. 476 – Adoption (Page 21) 11. Correspondence A. List of Correspondence to Wednesday, July 15, 2015 (Page 47) 12. New Business A. Consideration of Draft 2014 Annual Report (Page 87) B. 2015 Accounts Payable Listing (Page 135) All Council meetings are recorded, available at lionsbay.ca/municipal services/calendar. VoLB Regular Council Meeting - July 21, 2015 - Page 2 of 152 Agenda – Regular Meeting of Council – July 21, 2015 Village of Lions Bay Page 2 of 2 13. Public Questions & Comments 14. Resolution to Close Meeting BE IT RESOLVED THAT the Village of Lions Bay Council does close the July 21, 2015 Regular Council Meeting to the public on the basis of matters to be considered under the following section(s) of the Community Charter: 90 (1) A part of a council meeting may be closed to the public if the subject matter being considered relates to or is one or more of the following: a) personal information about an identifiable individual who holds or is being considered for a position as an officer, employee or agent of the municipality or another position appointed by the municipality; 15. -

Regular Meeting of the Council Agenda

VOLB Regular Council Meeting - July 4, 2017 - Page 1 of 166 REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE VILLAGE OF LIONS BAY HELD ON TUESDAY, JULY 4, 2017 at 7:00 PM COUNCIL CHAMBERS, 400 CENTRE ROAD, LIONS BAY AGENDA 1. Call to Order 2. Approval of Agenda 3. Public Participation (2 minutes per person totalling 10 minutes maximum) 4. Public Delegation Requests Accepted by Agenda Deadline (10 minutes maximum) 5. Review & Approval of Minutes of Prior Meetings A. Regular Council Meeting Minutes – June 20, 2017 (Page 7) THAT the Regular Council Meeting Minutes of June 20, 2017 be approved as circulated. 6. Business Arising from the Minutes 7. Unfinished Business A. Follow-Up Action Items from Previous Meetings # Meeting Date Description of Action Item Person Responsible 2 January 10, 2017 2017 Parking Plan Initiatives Karl & Staff 16 April 18, 2017 G6: Request to Support the Salish Sea Karl UNESCO World Heritage Site Application – Mayor Buhr to contact Salish Sea Trust for a stock letter to sign and support the initiative. 17 June 20, 2017 R1: Ray Kisser – staff to include response in Peter deliberation of Community Amenity Contribution policy when it comes to Council for consideration B. Temporary Use Permit Policy No. 1702 (Page 17) THAT the Temporary Use Permit Policy No. 1702 be adopted, as amended. VOLB Regular Council Meeting - July 4, 2017 - Page 2 of 166 Agenda – Regular Meeting of Council – July 4, 2017 Village of Lions Bay Page 2 of 5 C. Community Amenity Contribution Policy No. 1703 – On Table 8. Reports A. Staff i. CFO: 2017 Preliminary Mid-Year Review (Page 23) THAT the report “2017 Preliminary Mid-Year Review” be received for information purposes. -

City of North Vancouver CEEI Report Review and Comparison to Metro Municipalities Introduction

CEEI Report Review and Comparison to Metro Municipalities June 2009 www.cnv.org 141 West 14th Street North Vancouver BC V7M 1H9 | Tel: 604 985 7761 | Fax: 604 985 9417 | www.cnv.org City of North Vancouver City of North Vancouver CEEI Report Review and Comparison to Metro Municipalities Introduction The Province of British Columbia released the draft Community Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory (CEEI) in April 2009 to assist local governments in tracking and reporting annual community wide energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This initiative reduces burdens on local governments and data providers, supports higher-level GHG objectives and forwards the ability to make meaningful comparisons between communities. The City of North Vancouver has undertaken this analysis of the CEEI as part of its continued efforts towards sustainability in its own community. It views this report as an initial exploration of how the CEEI will enable local governments to evaluate more accurately their current GHG contributions and support the Provincial mandate for substantial reductions over the coming decade. Table of Contents: Section One: CEEI Report 1.1 Community Energy and Emissions 1.2 Methodology Section Two: City of North Vancouver CEEI 2.1 Emissions 2.2 Energy Consumption Section Three: Comparison of Metro Municipalities 3.1 Value of Comparative Analysis 3.2 Community Profiles 3.3 Emissions and Energy Consumption Profiles Appendix A: Limitations of the CEEI Data Appendix B: Report Sources CEEI Report Review Section One CEEI Report The first section of theCity of North Vancouver CEEI Report Review and Comparison to Metro Municipalities summarizes recent Provincial legislation regarding greenhouse gas emissions and introduces the CEEI format, methodology and limitations. -

Regular Meeting of the Council Agenda

Regular Council Meeting - May 22, 2018 - Page 1 of 122 REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE VILLAGE OF LIONS BAY HELD ON TUESDAY, MAY 22, 2018 at 7:00 PM COUNCIL CHAMBERS, 400 CENTRE ROAD, LIONS BAY AGENDA 1. Call to Order 2. Adoption of Agenda 3. Public Participation (2 minutes per person totalling 10 minutes maximum) 4. Public Delegation Requests Accepted by Agenda Deadline (10 minutes maximum) 5. Review & Approval of Minutes of Prior Meetings A. Regular Council Meeting – May 8, 2018 (Page 5) THAT the Regular Council Meeting Minutes of May 8, 2018 be approved as circulated. B. Special Council Meeting – May 11, 2018 (Page 13) THAT the Special Council Meeting Minutes of May 11, 2018 be approved as circulated. 6. Business Arising from the Minutes 7. Unfinished Business A. Follow-Up Action Items from Previous Meetings # Meeting Date Description of Action Item Person Responsible 32 February 6, 2018 Mayor Buhr and CAO DeJong to work on a Peter and Karl Terms of Reference for a Lions Bay Trail Maintenance Committee 34 March 20, 2018 G9: Maple Ridge Council to Minister Carole Karl James Re. Employer Health Tax 38 March 20, 2018 R4: Letter of Apology – school field damage Peter (follow up) 41 April 10, 2018 Beach park late close (letter was sent – staff Pam to add to Village Update) 42 April 24, 2018 IRR ID 159: Liquor Primary License – Peter Exploration of Cannabis Policy – staff to prepare a report 43 April 24, 2018 CAO to prepare a report on new TUPS and Peter enforcement Regular Council Meeting - May 22, 2018 - Page 2 of 122 Agenda – Regular Meeting of Council – May 22, 2018 Village of Lions Bay Page 2 of 3 45 April 24, 2018 Correspondence G2: Canada Infrastructure Karl Plan – Mayor Buhr to respond 46 May 8, 2018 Mayor Buhr to amend the letter to the Karl Ministry of Finance and send to the ministry 47 May 8, 2018 Correspondence R1: Wes Taylor Karl B. -

Village of Anmore Financial Sustainability Plan

Village of Anmore Financial Sustainability Plan FINAL REPORT October 2013 Prepared by: Vann Struth Consulting Group Inc. Prepared for: Village of Anmore TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 1 Project Objectives ......................................................................................................................... 1 Financial Sustainability ................................................................................................................. 2 Study Process ................................................................................................................................ 2 General Assumptions .................................................................................................................... 3 Structure of the Report ................................................................................................................ 4 2. BASELINE ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................... 6 Total Population ........................................................................................................................... 6 Population by Age ......................................................................................................................... 7 Housing Units and Residential Lots ............................................................................................. -

2021 Home Value Limits

2021 Home Value Limits To be eligible under BC RAHA, your home’s most recent BC Assessment value must not exceed the Home Value Limit for your Assessment Area, specified in the table below. To determine your assessment area code, refer to your Property Assessment Notice or use the table below. Assessment Area Code Assessment Area Home Value Limit 1 Capital $799,999 4 Central Vancouver Island $574,999 6 Courtenay $499,999 8 North Shore-Squamish Valley $1,349,999 9 Vancouver $1,374,999 10 North Fraser $974,999 11 Richmond-Delta $999,999 14 Surrey-White Rock $974,999 15 Fraser Valley $749,999 17 Penticton $449,999 19 Kelowna $649,999 20 Vernon $499,999 21 Nelson/Trail $399,999 22 East Kootenay $424,999 23 Kamloops $474,999 24 Cariboo $299,999 25 Northwest $349,999 26 Prince George $349,999 27 Peace River $299,999 The Home Value Limit for each Assessment Area is set by BC Housing using the data provided by BC Assessment and updated annually. The 2021 Home Value Limit for each area is established by ensuring that 60% of the homes in each area are valued at less than the Limit. Home Value Limits for use effective May 2021 Assessment Area by Jurisdiction Assessment Area Code Jurisdiction Name 1 Colwood, Victoria, Central Saanich, Esquimalt, Saanich, Oak Bay, Langford, North Saanich, Metchosin, Sooke, Highlands, View Royal, Sidney, Victoria Rural, Gulf Islands Rural 4 Duncan, Port Alberni, Nanaimo, North Cowichan, Lantzville, Ladysmith, Lake Cowichan, Parksville, Qualicum Beach, Tofino, Ucluelet, Duncan Rural, Nanaimo Rural, Alberni Rural 6 Courtenay, -

Area 79 District Numbers & Geographical Areas

BC Yukon Area 79 – District Numbers & Geographical Areas 21/12/2019 1 Alert Bay, Bella Bella, Fort Rupert, Kyuquot, Port 40 Coquitlam, Port Coquitlam, Port Moody Alice, Port Hardy, Port McNeill, Sointula, Zeballos 3 Black Creek, Campbell River, Cortes Island, Gold 41 Haney, Maple Ridge, Pitt Meadows, Webster’s Corner, River, Mansons Landing, Read Island, Quadra Whonnock Island, Sayward, Tahsis 4 Comox, Courtenay, Cumberland, Denman Island, 42 North Delta, Surrey Fanny Bay, Hornby Island, Merville 5 Lantzville, Nanaimo North 43 Aldergrove, Cloverdale, Fort Langley, Langley 6 Bamfield, Coombs, Lasqueti Island, Nanoose Bay, 44 Chehalis, Deroche, Mission, Lake Errok Parksville, Port Alberni, Qualicum Bay, Qualicum Beach, Tofino, Ucluelet 7 Cedar, Ladysmith, Nanaimo South, Gabriola Island 45 Agassiz, Boston Bar, Chilliwack, Cultus Lake, Hope, Harrison Mills, Rosedale, Sardis, Yarrow 8 Chemainus, Cobble Hill, Crofton, Duncan, 46 Davis Bay, Garden Bay, Gibsons, Madeira Park, Pender Honeymoon Bay, Lake Cowichan, Mill Bay, Youbou Harbour, Roberts Creek, Sechelt Thetis Island, Penelakut Island,Maple Bay,Cowichan Bay 9 Galiano Island, Mayne Island, Pender Island, Salt 47 Lund, Powell River, Texada Island Spring Island, Saturna Island 10 James Bay, Central Victoria, Esquimalt, Songhees, 50 Greenville, Hagwilget,Hartley Bay Hazelton Kitimat, James Bay, Vic West Kitamaat Village Kitkatla, Kitwancool, Kitwanga, Lax Kw’aalams New Aiyansh, Prince Rupert,Terrace,Stewart 12 Happy Valley, Langford, Metchosin, Sooke, View 51 Port Clements, Klemtu, Masset,