National Institute of Corrections Drug-Free Prison Zone Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Institution abbreviation, City, State and zip code. Prison Name Abbreviation City State Zip Avenal State Prison ASP Avenal CA 93204 California City Correctional Center CAC California City CA 93505 California State Prison, Calipatria CAL Calipatria CA 92233 California Correctional Center CCC Susanville CA 96130 California Correctional Institution CCI Tehachapi CA 93561 Centinela State Prison CEN Imperial CA 92251 Central California Women’s Facility CCWF Chowchilla CA 93610 California Health Care Facility CHCF Stockton CA 95215 California Institution for Men CIM Chino CA 91710 California Institution for Women CIW Corona CA 92878 California Men's Colony CMC San Luis Obispo CA 93409 California Medical Facility CMF Vacaville CA 95696 California State Prison, Corcoran COR Corcoran CA 93212 California Rehabilitation Center CRC Norco CA 92860 Correctional Training Facility CTF Soledad CA 93960 Chuckawalla Valley State Prison CVSP Blythe CA 92225 Deuel Vocational Institute DVI Tracy CA 95376 Folsom State Prison FSP Represa CA 95671 High Desert State Prison HDSP Susanville CA 96127 Ironwood State Prison ISP Blythe CA 92225 Kern Valley State Prison KVSP Delano CA 93216 California State Prison, Lancaster LAC Lancaster CA 93536 Mule Creek State Prison MCSP Ione CA 95640 North Kern State Prison NKSP Delano CA 93215 Pelican Bay State Prison PBSP Crescent City CA 95531 Pleasant Valley State Prison PVSP Coalinga CA 93210 RJ Donovan Correctional Facility RJD San Diego CA 92179 California State Prison, Sacramento SAC Represa CA 95671 Substance Abuse Treatment Facility SATF Corcoran CA 93212 Sierra Conservation Center SCC Jamestown CA 95327 California State Prison, Solano SOL Vacaville CA 95696 San Quentin SQ San Quentin CA 94964 Salinas Valley State Prison SVSP Soledad CA 93960 Valley State Prison VSP Chowchilla CA 93610 Wasco State Prison WSP Wasco CA 93280 N.A. -

State of California California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Adult Programs

STATE OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION ADULT PROGRAMS Annual Report Division of Addiction and Recovery Services June 2009 MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the Division of Addiction and Recovery Services (DARS) is to provide evidence-based substance use disorder treatment services to California’s inmates and parolees. CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION ADULT PROGRAMS DIVISION OF ADDICTION AND RECOVERY SERVICES MATTHEW L. CATE SECRETARY KATHRYN P. JETT UNDERSECRETARY, ADULT PROGRAMS C. ELIZABETH SIGGINS CHIEF DEPUTY SECRETARY (Acting), ADULT PROGRAMS THOMAS F. POWERS DIRECTOR DIVISION OF ADDICTION AND RECOVERY SERVICES SHERRI L. GAUGER DEPUTY DIRECTOR DIVISION OF ADDICTION AND RECOVERY SERVICES ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report was prepared by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitations’ (CDCR) Division of Addiction and Recovery Services’ (DARS) Data Analysis and Evaluation Unit (DAEU) with assistance from Steven Chapman, Ph.D., Assistant Secretary, Office of Research. It provides an initial summary of performance indicators, demographics and background information on the DARS Substance Abuse Treatment Programs. The information presented in this report is designed to assist the treatment programs and institutional staff in assessing progress, identifying barriers and weaknesses to effective programming, and analyzing trends, while establishing baseline points to measure outcomes. Under the direction of Bill Whitney, Staff Services Manager II; Gerald Martin, Staff Services Manager I; Sheeva Sabati, Research Analyst II; Ruben Mejia, Research Program Specialist; Krista Christian, Research Program Specialist, conducted extensive research and analysis for this report. Peggy Bengs, Information Officer II and Norma Pate, Special Assistant to the Deputy Director, DARS provided editorial contributions. NOTE: In 2007, DARS designed the Offender Substance Abuse Treatment Database to monitor and evaluate programs. -

Degrees of Freedom

February 2015 D of F EXPANDING COLLEGE OPPORTUNITIES for Currently and Formerly Incarcerated Californians Stanford Criminal Justice Center Chief Justice Earl Warren Stanford Law School Institute on Law and Social Policy UC Berkeley School of Law DEGREES OF FREEDOM: Expanding College Opportunities for Currently and Formerly Incarcerated Californians February 2015 A report of the Renewing Communities Initiative Acknowledgements This report was co-written by Debbie Mukamal, Rebecca Silbert, and Rebecca M. Taylor. This report is part of a larger initiative – Renewing Communities – to expand college opportunities for currently and formerly incarcerated students in California. Nicole Lindahl was a contributing author; Nicole Lindahl and Laura Van Tassel also provided research assistance for this report. The research and publication of this report has been supported by the Ford Foundation. The authors thank Douglas Wood of the Ford Foundation for his vision and leadership which catapulted this report. The authors are grateful to the many people who provided information, experience, and guidance in the development of this report. These individuals are listed in Appendix A. Any errors or misstatements in this report are the responsibility of the authors; the recommendations made herein may, or may not, be supported by the individuals listed in Appendix A. Founded in 2005, the Stanford Criminal Justice Center serves as a research and policy institute on issues related to the criminal justice system. Its efforts are geared towards both generating policy research for the public sector, as well as providing pedagogical opportunities to Stanford Law School students with academic or career interests in criminal law and crime policy. -

State of California

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR)/ RFP Number: SD15-00047 California Correctional Health Care Services (CCHCS) Exhibit H List of Participating CDCR Institutions and Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) Facilities HEALTHCARE REGISTRY SERVICES NETWORK MANAGEMENT PROVIDER LIST OF PARTICIPATING CDCR INSTITUTIONS Institution Institution Avenal State Prison (ASP) California Rehabilitation Center (CRC) 1 Kings Way 5th Street & Western Avenal, CA 93204 Norco, CA 92860 (559) 386-0587; Fax (559) 386-7461 (951) 737-2683; Fax: (909) 736-1488 California City Correctional Center (CAC) California State Prison–Corcoran (COR) 22844 Virginia Boulevard 4001 King Avenue California City, CA 93505 Corcoran, CA 93212-8309 (760) 373-1764; (760) 373-3529 (559) 992-8800 x7992; Fax (559) 992-6196 California Correctional Center (CCC) 711-045 Center Road California State Prison, Los Angeles County (LAC) Susanville, CA 96127 th (530) 257-2181 x4167; Fax (530) 252-3073 44750 60 Street West Lancaster, CA 93536-7620 (661) 729-2000 x7046; Fax: (661) 729-6909 California Correctional Institution (CCI) 24900 Highway 202 California State Prison – Sacramento (SAC) Tehachapi, CA 93561 Prison Road (661) 822-4402; Fax (661) 823-5043 Represa, CA 95671 (916) 985-8610; Fax (916) 294-3135 California Health Care Facility – Stockton (CHCF) California State Prison - San Quentin (SQ) 7707 South Austin Road San Quentin, CA 94964 Stockton, CA 95215 (415) 454-1460; Fax (415) 455-5091 (209) 467-2500; Fax (209) 467-4677 California Institution for Men (CIM) California -

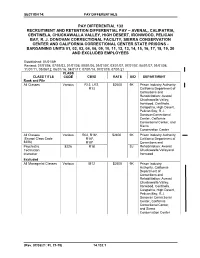

Pay Differentials

SECTION 14: PAY DIFFERENTIALS PAY DIFFERENTIAL 132 RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION DIFFERENTIAL PAY – AVENAL, CALIPATRIA, CENTINELA, CHUCKAWALLA VALLEY, HIGH DESERT, IRONWOOD, PELICAN BAY, R. J. DONOVAN CORRECTIONAL FACILITY, SIERRA CONSERVATION CENTER AND CALIFORNIA CORRECTIONAL CENTER STATE PRISONS - BARGAINING UNITS 01, 02, 03, 04, 06, 09, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 AND EXCLUDED EMPLOYEES Established: 01/01/89 Revised: 07/01/98, 07/01/03, 01/01/06, 09/01/06, 01/01/07, 03/01/07, 07/01/07, 08/01/07, 01/01/08, 11/01/11, 03/06/12, 06/01/16, 04/01/17, 07/01/18, 07/01/19, 07/01/21 CLASS CLASS TITLE CODE CB/ID RATE EID DEPARTMENT Rank and File All Classes Various R12, U12, $2600 9K Prison Industry Authority, R13 California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: Avenal, Chuckawalla Valley, Ironwood, Centinela, Calapatria, High Desert, Pelican Bay, R.J. Donovan Correctional Center, California Correctional Center, and Sierra Conservation Center All Classes Various R02, R16*, $2400 9K Prison Industry Authority, (Except Class Code R18*, California Department of 8226) R19* Corrections and Psychiatric 8226 R18 SJ Rehabilitation: Avenal, Technician Chuckawalla Valley and Instructor Ironwood Excluded All Managerial Classes Various M12 $2600 9K Prison Industry Authority, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: Avenal, Chuckawalla Valley, Ironwood, Centinela, Calapatria, High Desert, Pelican Bay, R.J. Donovan Correctional Center, California Correctional Center, and Sierra Conservation Center (Rev. 07/08/21: PL 21-19) 14.132.1 SECTION 14: PAY DIFFERENTIALS All Supervisory Classes Various S12, U12, $2600 9K Prison Industry S13 Authority, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: Avenal, Chuckawalla Valley, Ironwood, Centinela, Calapatria, High Desert, Pelican Bay, R.J. -

Master Plan Annual Report for Calendar Year 2020

MASTER PLAN ANNUAL REPORT FOR CALENDAR YEAR 2020 Submitted January 2021 CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION MASTER PLAN ANNUAL REPORT FOR CALENDAR YEAR 2020 KATHLEEN ALLISON Secretary JENNIFER BARRETTO Undersecretary Administration DEAN BORG Director Facility Planning, Construction and Management Chris Lief Deputy Director Facility Planning, Construction and Management Master Plan Annual Report for Calendar Year 2020 Prepared by: CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION FACILITY PLANNING, CONSTRUCTION AND MANAGEMENT CAPITAL PLANNING AND PROJECT SERVICES BRANCH MICHELLE WEAVER ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR PLANNING AND FINANCE SECTION MICHAEL POTTER CHIEF FACILITY PLANNING UNIT STAFF SARAH JOHNSON, MANAGER II JOSHUA HAMMONDS, MANAGER I JENNIFER BOSS, ANALYST RICK EASLEY, ANALYST STEVE MEDINGER, ANALYST BETH OLMSTEAD, ANALYST STEPHANIE SCHUMANN, ANALYST ERIC THOMPSON, ANALYST TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................ ES-1 Population – Adult Inmates ..................................................................................POP-1 Infrastructure ............................................................................................................ IN-1 Housing Needs .......................................................................................................... H-1 Adult Inmate Health Care ....................................................................................... -

Annual Escape Report 2009

ANNUAL ESCAPE REPORT CALENDAR YEAR 2009 Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Offender Information Services Branch Estimates and Statistical Analysis Section Data Analysis Unit Sacramento, California February 2010 Reference Number: BEH-4 STATE OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION MATTHEW CATE Secretary BRETT MORGAN Chief of Staff LEE SEALE Deputy Chief of Staff SCOTT KERNAN Undersecretary, Operations MARY FERNANDEZ Undersecretary, Administration STEVEN F. CHAPMAN, Ph. D. Assistant Secretary, Office of Research JAY R. ATKINSON Chief, Offender Information Services Branch VACANT Research Manager II, Estimates and Statistical Analysis Section DATA ANALYSIS UNIT VACANT Staff Services Manager I LORI ASUNCION STEPHEN KRIMETZ Associate Government Program Analyst Associate Information Systems Analyst DAVID WEISHAHN Associate Information Systems Analyst 1515 S STREET SACRAMENTO, CA 95811 TELEPHONE: (916) 445-1310 Internet: http://www.cdcr.ca.gov/Reports_Research/Offender_Information_Services_Branch/index.html Email: http://www.cdcr.ca.gov/Reports_Research/Offender_Information_Services_Branch/Contact_DAU.aspx Data Analysis Unit Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Estimates and Statistical Analysis Section State of California Offender Information Services Branch February 2010 ANNUAL ESCAPE REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights ....................................................................................................................... 1 Table 1 Escapes from Adult Institutions and Camps and Rate per 100 -

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Division of Correctional Policy Research and Internal Oversight Office of Research August 18, 2021

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Division of Correctional Policy Research and Internal Oversight Office of Research August 18, 2021 Weekly Report of Population As of Midnight August 18, 2021 Total CDCR Population Felon/ Change Since Change Since Design Percent Staffed Population Other Last Week Last Year Capacity Occupied Capacity A. Total In-Custody/CRPP Supervision 99,265 +135 -3,017 I. In-State 99,265 +135 -3,017 (Men, Subtotal) 95,367 +128 -3,084 (Women, Subtotal) 3,898 +7 +67 1. Institution/Camps 96,106 +118 -2,077 88,078 109.1 125,317 Institutions 94,398 +122 -1,698 84,710 111.4 121,923 Camps(CCC, CIW, and SCC) 1,708 -4 -379 3,368 50.7 3,394 2. In-State Contract Beds 2,084 +10 -1,154 Community Prisoner Mother Program 3 0 -10 California City Correctional Facility 2,081 +10 -108 3. Department of State Hospitals 182 +3 -55 4. CRPP Supervision 893 +4 +269 Alternative Custody Program 32 0 +8 Custody to Community Treatment Reentry Program 293 0 +79 Male Community Reentry Program 475 +4 +133 Medical Parole 66 -1 +34 Medical Reprieve Program 23 +1 Medically Vulnerable Release 4 0 -8 B. Parole 48,327 -203 -7,225 Community Supervision 46,795 -195 -7,154 Interstate Cooperative Case 1,532 -8 -71 C. Non-CDCR Jurisdiction 2,879 -138 +1,688 Other State/Federal Institutions 250 -1 -54 Out of State Parole 752 -3 +10 Out of State Parolee at Large 16 0 -1 DJJ-W&IC 1731.5(c) Institutions 9 0 -8 County Jail 1,852 -134 +1,741 D. -

Chapter 4 Classification, Housing, and Programs

The California Prison and Parole Law Handbook by Heather MacKay and the Prison Law Office THE CALIFORNIA PRISON & PAROLE LAW HANDBOOK BY HEATHER MACKAY & THE PRISON LAW OFFICE ISBN: 978-0-692-95526-0 Copyright © 2019 by the Prison Law Office Content Editor: Ritika Aggarwal Production & Style Editor: Brandy Iglesias Cover Art: Justus Evans Cover Design: Tara Eglin Assistance with Chapter 9: Kony Kim, former Staff Attorney at UnCommon Law, a non-profit that represents people at Board of Parole Hearings proceedings, challenges unjust parole policies and decisions, and provides training and information to people serving life terms and their advocates. Assistance with Chapter 11: Anne Mania, former Staff Attorney at the Prison Law Office and Rosen, Bien, Galvan and Grunfeld, where she worked on ensuring due process for people undergoing parole violation processes. Assistance with Chapter 13: Theo Cuison, Deputy Director and Clinical Supervisor in the Immigration Unit of the East Bay Community Law Center (EBCLC), a clinic of U.C. Berkeley School of Law. The Prison Law Office is a non-profit public interest law firm that strives to protect the rights and improve the living conditions of people in state prisons, juvenile facilities, jails and immigration detention in California and elsewhere. The Prison Law Office represents individuals, engages in class actions and other impact litigation, educates the public about prison conditions, and provides technical assistance to attorneys throughout the country. Order forms for The California Prison and Parole Law Handbook are available at: www.prisonlaw.com or by writing to: Prison Law Office General Delivery San Quentin, CA 94964 In addition, many self-help information packets on a variety of topics are available free of charge on the Resources page at www.prisonlaw.com or by contacting the Prison Law Office at the address above. -

California State Superior Courts

CALIFORNIA STATE COURTS (and state prisons in those court districts) California State Superior Courts Alameda County Superior Court 1225 Fallon Street, #209 Oakland, CA 94612-4293 Alpine County Superior Court 14777 State Route 89 PO Box 518 Markleeville, CA 96120 Amador County Superior Court 500 Argonaut Lane Jackson, CA 95642 Mule Creek State Prison Butte County Superior Court One Court Street Oroville, CA 95965 Calaveras County Superior Court 891 Mountain Ranch Road San Andreas, CA 95249-9709 Colusa County Superior Court 532 Oak St. Colusa, CA 95932-2495 Contra Costa County Superior Court 725 Court Street Martinez, CA 94553-1233 Del Norte County Superior Court 450 H Street, Room 209 Crescent City, CA 95531 Pelican Bay State Prison El Dorado County Superior Court 495 Main Street Placerville, CA 95667-5699 Fresno County Superior Court 1100 Van Ness Fresno, CA 93724-0002 Pleasant Valley State Prison Glenn County Superior Court 526 West Sycamore Street Willows, CA 95988 Humboldt County Superior Court 825 Fifth Street Eureka, CA 95501-1153 Imperial County Superior Courts 939 West Main Street El Centro, CA 92243-2842 Calipatria State Prison, Centinela State Prison Inyo County Superior Court 168 Edwards Street Independence, CA 93526-0618 Kern County Superior Court 1415 Truxtun Avenue Bakersfield, CA 93301-4172 Cal. Correctional Institution, Kern Valley State Prison, North Kern State Prison, Wasco State Prison Kings County Superior Court 1426 South Drive Hanford, CA 93230-5997 Avenal State Prison, CSP-Corcoran, Substance Abuse Treatment Facility -

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Recidivism Reduction Program Inventory

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Recidivism Reduction Program Inventory Prepared by: Jesse Jannetta Center for Evidence-Based Corrections University of California, Irvine April 30, 2007 Contents Introduction - 2 Prison Programs - 4 Academic Courses - 4 Bridging Education Program (BEP) - 6 Carpentry Pre-Apprenticeship Program - 8 Community Prisoner Mother Program (CPMP) - 9 Conflict Anger Lifelong Management (CALM) - 11 Drug Treatment Furlough - 13 Elementary Secondary Education Act (ESEA) - 15 Family Foundations Program (FFP) - 17 Inmate Employability Program (IEP) - 19 Offender Employment Continuum (OEC) - 21 Re-Entry Education - 23 S.T.A.N.D. U.P. (Successful Transitions and New Directions Utilizing Partnerships) - 25 Substance Abuse Programs (SAP’s) - 27 Amity Foundation at R. J. Donovan Correctional Facility - 29 Center Point at California Institution for Men - 31 CiviGenics, Inc. Correctional Recovery Academy - 33 Mental Health Systems, Inc.—AMEND - 36 Phoenix House – CSP Corcoran - 38 Walden House -California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility,Yard F - 40 Transitional Treatment Program (TTP) - 43 Vocational Education - 45 Parole Programs - 46 Community-Based Coalition (CBC) - 46 Community Re-Entry Partnerships (CRP) - 48 Computer Literacy Learning Centers (CLLC) - 50 Day Reporting Center (DRC) - 52 Employment Development Department (EDD) Program - 55 Female Offender Treatment and Employment Program (FOTEP) - 56 In-Custody Drug Treatment Program (ICDTP) - 58 Parolee Employment Program (PEP) - 60 Parolee Service -

EXHIBIT a Case 4:01-Cv-01351-JST Document 3468-1 Filed 10/15/20 Page 2 of 9 Exhibit a Population As of October 7, 2020

Case 4:01-cv-01351-JST Document 3468-1 Filed 10/15/20 Page 1 of 9 EXHIBIT A Case 4:01-cv-01351-JST Document 3468-1 Filed 10/15/20 Page 2 of 9 Exhibit A Population as of October 7, 2020 Institution Design Capacity Actual Population Population as % of design capacity Total housed in adult institutions1 85,083 92,616 108.9% Total housed in camps 1,773 Total housed out of state 0 Individual CDCR Institutions - Men Avenal State Prison 2,920 3,535 121.1% California State Prison, Calipatria 2,308 2,931 127.0% California Correctional Center* 3,883 2,524 65.0% California Correctional Institution 2,783 3,082 110.7% California State Prison, Centinela 2,308 3,145 136.3% California Health Care Facility, Stockton 2,951 2,466 83.6% California Institution for Men 2,976 2,283 76.7% California Men's Colony 3,838 3,190 83.1% California Medical Facility 2,361 2,082 88.2% California State Prison, Corcoran 3,116 3,198 102.6% California Rehabilitation Center 2,491 2,345 94.1% Correctional Training Facility 3,312 4,377 132.2% Chuckawalla Valley State Prison 1,738 1,911 110.0% Deuel Vocational Institution 1,681 1,571 93.5% Folsom State Prison 2,066 2,242 108.5% High Desert State Prison 2,324 3,355 144.4% Ironwood State Prison 2,200 2,914 132.5% Kern Valley State Prison 2,448 3,529 144.2% California State Prison, Los Angeles 2,300 2,863 124.5% Mule Creek State Prison 3,284 3,805 115.9% North Kern State Prison 2,694 1,856 68.9% Pelican Bay State Prison 2,380 2,305 96.8% Pleasant Valley State Prison 2,308 2,828 122.5% RJ Donovan Correctional Facility 2,992 3,571