Ukrainian Settlement Patterns on the Canadian Prairies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doukhobor Problem,” 1899-1999

Spirit Wrestling Identity Conflict and the Canadian “Doukhobor Problem,” 1899-1999 By Ashleigh Brienne Androsoff A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, in the University of Toronto © by Ashleigh Brienne Androsoff, 2011 Spirit Wrestling: Identity Conflict and the Canadian “Doukhobor Problem,” 1899-1999 Ashleigh Brienne Androsoff Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, University of Toronto, 2011 ABSTRACT At the end of the nineteenth century, Canada sought “desirable” immigrants to “settle” the Northwest. At the same time, nearly eight thousand members of the Dukhobori (commonly transliterated as “Doukhobors” and translated as “Spirit Wrestlers”) sought refuge from escalating religious persecution perpetrated by Russian church and state authorities. Initially, the Doukhobors’ immigration to Canada in 1899 seemed to satisfy the needs of host and newcomer alike. Both parties soon realized, however, that the Doukhobors’ transition would prove more difficult than anticipated. The Doukhobors’ collective memory of persecution negatively influenced their perception of state interventions in their private affairs. In addition, their expectation that they would be able to preserve their ethno-religious identity on their own terms clashed with Canadian expectations that they would soon integrate into the Canadian mainstream. This study focuses on the historical evolution of the “Doukhobor problem” in Russia and in Canada. It argues that -

PF Vol. 08 No.02.Pdf (13.31Mb)

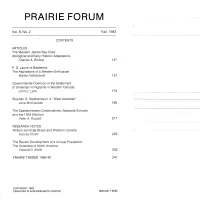

PRAIRIE FORUM Vol. 8, NO.2 Fall, 1983 CONTENTS ARTICLES The Western James Bay Cree: Aboriginal and Early Historic Adaptations Charles A. Bishop 147 P. G. Laurie of Battleford: The Aspirations of a Western Enthusiast Walter Hildebrandt . 157 Governmental Coercion in the Settlement of Ukrainian Immigrants in Western Canada John C. Lehr 179 Stephan G. Stephansson: A "West Icelander" Jane McCracken 195 The Saskatchewan Conservatives, Separate Schools and the 1929 Election Peter A. Russell 211 RESEARCH NOTES William Jenninqs Bryan and Western Canada Harvey Strum 225 The Recent Development of a Unique Population: The Hutterites of North America Edward D. Boldt 235 PRAIRIE THESES, 1980-81 241 COPYRIGHT 1983 CANADIAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER ISSN 0317 -6282 BOOK REVIEWS DEN OTTER, A. A., Civilizing the West: The GaIts and the Development of Western Canada by Michael J. Carley 251 DEN OTTER, A. A., Civilizing the West: The GaIts and the Development of Western Canada _ by Carl Betke .................................................. .. 252 FOSTER, JOHN (editor), The Developing West, Essays on Canadian History in Honour of L. H. Thomas by Donald B. Wetherell. ......................................... .. 254 MACDONALD, E. A., The Rainbow Chasers by Simon Evans 258 KERR, D., A New Improved Sky by William Latta 260 KERR, D. C. (editor), Western Canadian Politics: The Radical Tradition by G. A. Rawlyk 263 McCRACKEN, JANE, Stephan G. Stephansson: The Poet of the Rocky Mountains by Brian Evans. ................................................ .. 264 SUMMERS, MERNA, Calling Home by R. T. Robertson 266 MALCOLM, M. J., Murder in the Yukon: The Case Against George O'Brien by Thomas Thorner 268 KEITH, W. J., Epic Fiction: The Art of Rudy Wiebe by Don Murray 270 STOWE, L., The Last Great Frontiersman: The Remarkable Adventures of Tom Lamb by J. -

Ariail Family Cemetery Surveys

ARIAIL FAMILY CEMETERY SURVEYS WHAT IS A CEMETERY? Lives are commemorated Deaths are recorded Families are reunited Memories are made tangible And love is undisguised. Communities accord respect Families bestow reverance Historians seek information and Our heritage is thereby enriched. Testimonies of devotion, pride and remembrance are cased in bronze to pay warm tribute to accomplishments and to the life, not the death, of a loved one. The cemetery is homeland for memorials that are a sustaining source of comfort to the living. A cemetery is a history of people -- a perpetual record of yesterday and a sanctuary of peace and quiet today. A cemetery exists because every life is worth loving and remembering -- A L W A Y S! SUCH ARE THE ARIAIL CEMETERIES We would like to gratefully acknowledge a cousin of ours from Canada, by the name of Valerie, who has devoted of her time to organize the material in this document for more efficient usage by people visiting the family web site. CREMATED Lawrence Richard Love, b. Apr 15, 1927, d. Feb 12, 2013, died Johnson City, Tenn. Percy Alen Gray, b. Jun 27, 1899, d. Apr 5, 1957, died San Francisco, California. Gladys Georgie Faucett Gray, b. Jun 13, 1899, d. Nov 10, 1989, died Alameda, California. Sylvester Stanley Novak, b. Dec 6, 1908, d. Oct 8, 1990, died Hennepin, Minnesota. Clara T. Anderson Novak, b. Oct 31, 1913, d. Oct 11, 1988, Hennepin, Minnesota. Robin Ethel Dunham Smith, b. Mar 12, 1927, d. Dec 23, 2003, Walnut Creek, California. Fred A. “Junius” Woodruff, b. -

“…With a Stout Wife” Doukhobor Women's

“…With A Stout Wife” Doukhobor Women’s Challenge to the Canadian (Agri)Cultural Ideal Draft Paper, Long Form Rural History Conference, Bern (Switzerland), August 2013 Dr. Ashleigh Androsoff Faculty, Dept. of History Douglas College (Canada) Fleeing religious persecution in Russia, nearly 8000 Doukhobors immigrated to Canada in 1899 to take up free homestead land in the Northwest.1 Repeated exile to the remote outreaches of the Russian empire had prepared them well for the challenges associated with adapting to new and unfavourable conditions despite limited resources. Their reputation for hard work and agricultural acumen made them attractive as prospective prairie settlers. Though these qualities recommended them for the rigours of farm labour, their fit as prospective Canadians was called into question soon after their arrival. Some of their more “reluctant hosts”2 wondered whether Russian “serfs” would have trouble adjusting to Canadian political and economic practices.3 These “vestiges of serfdom” were evident within a few months of their arrival: while most settlers depended on teams of horses or oxen to break the soil, the Doukhobors depended on their women. Descriptions and photographs of Doukhobor women harnessed to their ploughs in place of draught animals were widely circulated in 1899 and thereafter. These have often been reproduced in volumes focused on Canadian immigration, minorities, women, agricultural, and prairie history, as well as in general Canadian history survey textbooks. Graphic and narrative accounts of this incident have been used at the time and since as evidence of the Doukhobors’ particular strangeness. At best it has been used to demonstrate the Doukhobors’ exceptional physical size and strength: even the women of the group were strong enough to take the place of horses. -

Descendants of Thomas Codd

Descendants of Thomas Codd Generation No. 1 2 1 1 1. THOMAS CODD (? ) was born 1773 in Munahullen, Aghowle Parish, Shillelagh Barony, Co. Wicklow, Ireland1, and died 23 July 1852 in Lanark Twp., Lanark Co., 1 1 Ontario, Canada . He married LADY ELIZABETH TWAMLEY . She was born 1774 in Cronelea, Mullancuff Parish, Half Barony Shillelagh, Co. Wicklow, Ireland1, and died 20 October 1839 in Lanark Twp., Lanark Co., Ontario, Canada1. Notes for THOMAS CODD: Notes from Eileen Jackson: 1. Thomas and Elizabeth Codd and their five children arrived in Canada in 1820, "and in the month of August of the same year proceeded to Lanark to obtain land." (See Upper Canada Land Petition's, 27 August 1828, p. 106). Thomas Codd and his son George located on lots 3N.E.½, 4, and 5, concession 12. George obtained the patent for lot 4S.W.½. 2. Family information is that the outcome of a dispute about a political issue accounts for the difference in the spelling of the surname Codd in Canada. Thomas Sr., and his son Richard selected "Coad", George, Thomas, Abraham, and James decided on "Code". Codes who settled in Kitley in Leeds were also divided as to how they spelled the surname. Family information is that they were relatives of Thomas Codd. 3. E Jackson 12 Mar 1988 p1 "Carol Bennett has written three books, the first "In Search of Lanark" was based on newspaper articles. There is a picture of our Jackson homestead in it - C12L12 Lanark twp - Boyds Settlement." NOTES ON THE DESCENDENTS OF THOMAS CODD AND ELIZABETH TWAMELY, NATIVES OF WICKLOW, IRE, EMIGRATED 1820, located Con 12 lots 3(part) 4 and 4 Lanark Township. -

Reel Time: Movie Exhibitors and Movie Audiences in Prairie Canada

REEL TIME MOVIE EXHIBITORS � MOVIE AUDIENCES in prairie canada, 1896 to 1986 Robert M. Seiler and Tamara P. Seiler Copyright © 2013 Robert M. Seiler and Tamara P. Seiler Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-926836-99-7 (print) 978-1-927356-00-5 (pdf) 978-1-927356-01-2 (epub) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printers. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Seiler, R. M. (Robert Morris) Reel time : movie exhibitors and movie audiences in prairie Canada, 1896 to 1986 / by Robert M. Seiler and Tamara P. Seiler. Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued also in electronic formats. isbn 978-1-926836-99-7 1. Motion pictures — Social aspects — Prairie Provinces — History. 2. Motion pictures — Economic aspects — Prairie Provinces — History. 3. Motion picture theaters — Social aspects — Prairie Provinces — History. 4. Motion picture theaters — Economic aspects — Prairie Provinces — History. i. Seiler, Tamara Palmer ii. Title. pn1995.9.s6s44 2013 302.23'4309712 c2012-901800-7 We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Can- ada Book Fund (cbf) for our publishing activities. Assistance provided by the Government of Alberta, Alberta Multimedia Devel opment Fund. This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution–Noncom- mercial–No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada: see www.creativecommons.org. The text may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that credit is given to the original author. To obtain permission for uses beyond those outlined in the Creative Commons license, please contact AU Press, Athabasca University, at [email protected].