THE LINCOLN BUILDING, 1-3 Union Square West, Borough of Manhattan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Where Architecture Expert Paul Goldberg Comments on the History of New York's Famous Skyscrapers. As You Do So, Complete

Can you identify any of these buildings? What do they all have in common? Which one do you like best? Read where architecture expert Paul Goldberg comments on the history of New York’s famous skyscrapers. As you do so, complete the following tasks: · In New York buildings are not only buildings, they become ___________________ · New York took over Chicago as regards skyscrapers in ___________________. · The Woolworth building was the tallest building worldwide for _________________. · The _______________ defined the Manhattan skyline. · They are trying to keep a memory of the people who were lost and also to show New York’s ______________________________. · New York stands out from the other cities as the embodiment of ____________________. Woolworth Building; Empire State Building; Chrysler Building; Flatiron; Hearst Tower The Woolworth Building, at 57 stories (floors), is one of the oldest—and one of the most famous—skyscrapers in New York City. It was the world’s tallest building for 17 years. More than 95 years after its construction, it is still one of the fifty tallest buildings in the United States as well as one of the twenty tallest buildings in New York City. The building is a National Historic Landmark, having been listed in 1966. The Empire State Building is a 102-story landmark Art Deco skyscraper in New York City at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and West 34th Street. Like many New York building, it has become seen as a work of art. Its name is derived from the nickname for New York, The Empire State. It stood as the world's tallest building for more than 40 years, from its completion in 1931 until construction of the World Trade Center's North Tower was completed in 1972. -

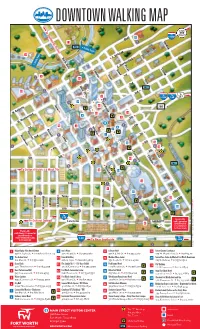

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

11 Houston Street Greenock PA16 8DA

11 HOUSTON STREET Greenock PA16 8DA Residential Development Opportunity 11 Houston Street Greenock 2 OPPorTUNITY We are delighted to present a site to the market at 11 Houston Street, Greenock which lies close to the Greenock waterfront. The available site extends to approximately 0.35 acres (0.14 hectares) and previously had planning consent for the development of 22 apartments with 26 surfaced car parking spaces. A suite of technical information is available for review upon registration of interest. LOCATION The site is set on the western edge of Greenock Town Centre on Houston Street. Greenock is the largest town within the Local Authority area of Inverclyde. It lies approximately 27 miles west of the City of Glasgow on the southern side of the Firth of Clyde. Greenock has historically been one of the most important Scottish ports and whilst not at the same level of activity as it once was, is still a thriving port and provides docking for Ocean Liners. Greenock provides a wide range of retail and leisure offers within close proximity of the subjects and has excellent road and public transport connections to Glasgow and the surrounding areas. The M8 motorway provides direct access to Glasgow and Edinburgh and Greenock has an extensive rail network with the nearest station to the site being Greenock West station which lies approximately 0.6 miles south east of the subjects. This provides rail connections to Glasgow and Paisley. Ferry Services in nearby Gourock provide passengers and cars with access to Dunoon and Kilcreggan. In close proximity to the subjects there are a number of local amenities such as Ardgowan Bowling Club, Greenock Cricket Club and Greenock Golf Club. -

New York City Adventure “One If by Land, and Two If by Sea”

NYACK COLLEGE HOMECOMING NEW YORK CITY ADVENTURE “ONE IF BY LAND, AND TWO IF BY SEA” 1 READE S T REE T WASHINGTON MARKET C PARK H G CIV I C T E URC W REE E C E N T E R O ROCKEFELLER C H A M B ERS S T REE T R PARK T E T R K R S RE A T S P N H L WE N W O N R W A RRE N S T REE T S DIS O A A M I C H E R P T T S H R I RE T 2 V E TRI B E C A N E R D AVEN W E T E N K F O R T S T R E CITY O F R A MSURRA YB ST REE T T E HALL BR E T SP W T R O RR PARK R K R O KLY ASHI A L RE O P A U N A P A R K P L A C E S P R U C E S B E D O V E R C RID N A E N G A E S T E MURR A Y S T REE T G T RE RE D D E T E T T T E T 3 Y O E W E N B T B A RCL A Y STREE T E T RE E E LL K M A E T A A N T S S T E RE E RE TRE Y T T S RE M T S R L A P E A I A C K S L L E E L H P I L D I P V ESEY S T REE T E R S T R E T A N N S T R E E T O T W G B EE A T N 4 K W W M A N ES FUL T O N STREE T FRO FU 5 H T C L D E Y T T W O RLD W O RLD T R A D E O S FINA N C I A L C E N T ER SI T E DU F N F T C E N T E R J O H N T S T R E CLI RE E T E T S O U T H S T R E E T T C O R T L A N D T Y E E E S E A P O R T Pier 17 A E M J O T A IDEN E PL H N S T A T T R W S T R R RE N O R T H L E T E E A N T T C O V E D E PEARL STRE T S A T S L I B ERT Y S T REE T LIBER FL W GREENWICH S E R T O T C H Y E R Pedestrian A U S T Bridge S I RE E T H N M CEDA R CED A R S T REE T A I M N BR AID I A S G E T N I T C E L S D A O Y T H A M E S A R S T N L R E E N E T T B AT T E R Y A S L A L B A N Y S T REE T T P O E S RE I PA R K N P U I N E S T T L R E E T T RE E P I N W E CIT Y H A E T T E RE CARLISLE S T REE T T -

Improving the Technical Knowledge and Background Level in Engineering Training by the Education Digitalization Process

E3S Web of Conferences 273, 12099 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127312099 INTERAGROMASH 2021 Improving the technical knowledge and background level in engineering training by the education digitalization process Konstantin Kryukov, Svetlana Manzhilevskaya*, Konstantin Tsapko, and Irina Belikova Don State University, 344000, Rostov-on-Don, Russia Abstract. The modern technical education digitalization implies an increase in the role of the information component in the training of students. At the same time there is a certain gap between the modern technologies training and the understanding of the fact that construction industry is the mixture of historically formed features and the current state of the industry. Nowadays construction industry is under continuous technical development. The main danger of an insufficient attention to the special aspects of the construction development is the neglect of the preservation of cultural background and architectural heritage, which can be observed in the modern life. The article deals with the issues of improving the effectiveness of the educational process of students by introducing into the educational training process not only modern methods of designing building structures, but also the issues of understanding the history of the emergence of individual construction objects. The construction object can't appear out of nothing. All constructive solution is preceded by a historical situation the situation of cultural and architectural heritage. However, there is no discernible connection between technical education and the humanities and social sciences. The authors use historical examples to justify the need for the use of elements of the humanities by a teacher of a higher technical educational institution with the introduction of the capabilities of modern digital information modeling technologies. -

Historic Lower Manhattan

Historic Lower Manhattan To many people Lower Manhattan means financial district, where the large buildings are designed to facilitate the exchange of money. The buildings, streets and open spaces, however, recall events that gave birth to a nation and have helped shape the destiny of western civilization. Places such as St. Paul's Chapel and Federal Hall National Memorial exemplify a number of sites which have been awarded special status by the Federal Government. The sites appearing in this guide are included in the following programs which have given them public recognition and helped to assure their survival. National Park Service Since its inauguration in 1916, the National Park Service has been dedicated to the preservation and management of our country's unique national, historical and recreational areas. The first national park in the world—Yellowstone—has been followed by the addition of over 300 sites in the 50 states, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. National Park areas near and in Manhattan are: Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site, Fire Island National Seashore, Gateway National Recreation Area, Sagamore Hill National Historic Site, Hamilton Grange National Memorial, and General Grant National Memorial. National Historic Landmarks National Park Service historians study and evaluate historic properties throughout the country. Acting upon their findings the Secretary of the Interior may declare the properties eligible for designation as National National Parks are staffed by Park Rangers who can provide information As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the Historic Landmarks. The owner of such a property is offered a certif to facilitate your visit to Lower Manhattan. -

Report: Federal Houses Landmarked Or Listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places 1999

GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION Making the Case Federal Houses Landmarked or Listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places 1999-2016 The many surviving Federal houses in Lower Manhattan are a special part of the heritage of New York City. The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation has made the documentation and preservation of these houses an important part of our mission. This report highlights the Society’s mission in action by showing nearly one hundred fifty of these houses in a single document. The Society either proposed the houses in this report for individual landmark designation or for inclusion in historic districts, or both, or has advocated for their designation. Special thanks to Jiageng Zhu for his efforts in creating this report. 32 Dominick Street, built c.1826, landmarked in 2012 Federal houses were built between ca. 1790 to ca. 1835. The style was so named because it was the first American architectural style to emerge after the Revolutionary War. In elevation and plan, Federal Period row houses were quite modest. Characterized by classical proportions and almost planar smoothness, they were ornamented with simple detailing of lintels, dormers, and doorways. These houses were typically of load bearing masonry construction, 2-3 stories high, three bays wide, and had steeply pitched roofs. The brick facades were laid in a Flemish bond which alternated a stretcher and a header in every row. All structures in this report were originally built as Federal style houses, though -

Old Buildings, New Views Recent Renovations Around Town Have Uncovered Views of Manhattan That Had Been Hiding in Plain Sight

The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 Old Buildings, New Views Recent renovations around town have uncovered views of Manhattan that had been hiding in plain sight. By Caroline Biggs Impressions: 43,264,806 While New York City’s skyline is ever changing, some recent construction and additions to historic buildings across the city have revealed some formerly hidden, but spectacular, views to the world. These views range from close-up looks at architectural details that previously might have been visible only to a select few, to bird’s-eye views of towers and cupolas that until The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 recently could only be viewed from the street. They provide a novel way to see parts of Manhattan and shine a spotlight on design elements that have largely been hiding in plain sight. The structures include office buildings that have created new residential spaces, like the Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan; historic buildings that have had towers added or converted to create luxury housing, like Steinway Hall on West 57th Street and the Waldorf Astoria New York; and brand-new condo towers that allow interesting new vantages of nearby landmarks. “Through the first decades of the 20th century, architects generally had the belief that the entire building should be designed, from sidewalk to summit,” said Carol Willis, an architectural historian and founder and director of the Skyscraper Museum. “Elaborate ornament was an integral part of both architectural design and the practice of building industry.” In the examples that we share with you below, some of this lofty ornamentation is now available for view thanks to new residential developments that have recently come to market. -

Feature Property

Woolworth Building An early skyscraper, National Historic Landmark since 1966, and New York City landmark since 1983, the Woolworth Building was the tallest building in the world upon completion in 1913 until 1930. 233 Broadway New York, NY Neo-Gothic Style Façade Architectural Details Straight lines of the “piers” ascend upwards to the over-scaled pyramidal cap Top Portion of Building 57th Floor Observation Deck until 1940 Building Use Transition U-Shaped Portion- 29 Stories Tall Top 30 Floors Conversion to Luxury Residential Condominiums Lobby Details Marble Finishes Vaulted Ceiling Mosaics Stained-Glass Ceiling Light Bronze Fittings PROJECT SUMMARY Project Description A classic early high-rise architectural landmark incorporating Gothic themes with the modern idea of a skyscraper. The 1913 Gothic Revival building featured gargoyles, arches and flying buttresses. Bordered by Broadway, Barclay Street, Church Street, and Park Place, the building is located in New York City’s Financial District. Building Description 57 floor, Neo-Gothic designed, steel-rigid frame structure with light gray, limestone-colored, glazed, terra-cotta façade Official Building Name Woolworth Building Location 233 Broadway, New York City, NY Construction Start - 1910 | Completion- 1913 History Tallest building in the World 1913 - 1930 Named the “Cathedral of Commerce” upon completion Construction Cost $13.5 million LEADERSHIP | PROJECT TEAM | DESIGN | CONSTRUCTION U.S. President Woodrow Wilson New York City Mayor William Jay Gaynor Building Owner 1913 F.W. Woolworth Company Developer F.W. Woolworth Company & Irving National Exchange Bank Architect Cass Gilbert Structural Engineering Gunvald Aus Company Primary Contractor Thompson-Starrett & Company Current Use Office | Residential (top 30 floors) BUILDING CONSTRUCTION & AMENITIES SUMMARY Size 1.3 Million GSF Height 792 Feet | 241 Meters Number of Floors 57 (above ground) Design 57 floor, Neo-Gothic architectural style, featuring gargoyles, arches and flying buttresses. -

Gwendolyn Wright

USA modern architectures in history Gwendolyn Wright REAKTION BOOKS Contents 7 Introduction one '7 Modern Consolidation, 1865-1893 two 47 Progressive Architectures, ,894-'9,8 t h r e e 79 Electric Modernities, '9'9-'932 fau r "3 Architecture, the Public and the State, '933-'945 fi ve '5' The Triumph of Modernism, '946-'964 six '95 Challenging Orthodoxies, '965-'984 seven 235 Disjunctures and Alternatives, 1985 to the Present 276 Epilogue 279 References 298 Select Bibliography 305 Acknowledgements 3°7 Photo Acknowledgements 3'0 Index chapter one Modern Consolidation. 1865-1893 The aftermath of the Civil War has rightly been called a Second American Revolution.' The United States was suddenly a modern nation, intercon- nected by layers of infrastructure, driven by corporate business systems, flooded by the enticements of consumer culture. The industrial advances in the North that had allowed the Union to survive a long and violent COll- flict now transformed the country, although resistance to Reconstruction and racial equality would curtail growth in the South for almost a cen- tury. A cotton merchant and amateur statistician expressed astonishment when he compared 1886 with 1856. 'The great railway constructor, the manufacturer, and the merchant of to-day engage in affairs as an ordinary matter of business' that, he observed, 'would have been deemed impos- sible ... before the war'? Architecture helped represent and propel this radical transformation, especially in cities, where populations surged fourfold during the 30 years after the war. Business districts boasted the first skyscrapers. Public build- ings promoted a vast array of cultural pleasures) often frankly hedonistic, many of them oriented to the unprecedented numbers of foreign immi- grants. -

View Printable Directions

MANHATTAN CAMPUS OF THE VA NY HARBOR HEALTHCARE SYSTEM 423 East 23rd Street New York, NY 10010-5011 PUBLIC TRANSIT By Subway: The IRT "N" and "R" trains stop at 23rd Street and Broadway. The "1" and "9" trains stop at 23rd Street and 7th Avenue. The "6" train stops at 23rd Street and Park Avenue South. Take the "L" train to 14th Street. Exit at the 18th Street exit and walk five blocks to the hospital. By Bus: The M16 stops directly across from the hospital on 23rd Street. This bus can be boarded by Penn Station near the corner of 34th Street & 8th Avenue and 34th Street & 7th Avenue. The M15 picks up and drops off at the intersection of 23rd Street and 1st Avenue. The M23 stops at 1st Avenue and 23rd Street. The Command Bus from Brooklyn stops at 23rd Street and 1st Avenue. DRIVING DIRECTIONS By Car From Newark Airport: Take US 1/9 North to the Pulaski Skyway to the Holland Tunnel. Proceed to the Alternate Canal Street exit (3rd right) and make a left at the 2nd light at 6th Avenue. Turn right on Houston Street, then left on 1st Avenue and right on 23rd Street. By Car From the George Washington Bridge: Take the Cross Bronx Expressway to the Major Deegan Expressway (Rt 87) South to the FDR Drive South. Exit at 23rd Street. During construction, however, you are forced to drive onto 25th Street, so make an immediate left on Asser Levy Place to 23rd Street. The hospital is on the right. -

Leisure Pass Group

Explorer Guidebook Empire State Building Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Advanced reservations are required. You will not be able to enter the Observatory without a timed reservation. Please visit the Empire State Building's website to book a date and time. You will need to have your pass number to hand when making your reservation. Getting in: please arrive with both your Reservation Confirmation and your pass. To gain access to the building, you will be asked to present your Empire State Building reservation confirmation. Your reservation confirmation is not your admission ticket. To gain entry to the Observatory after entering the building, you will need to present your pass for scanning. Please note: In light of COVID-19, we recommend you read the Empire State Building's safety guidelines ahead of your visit. Good to knows: Free high-speed Wi-Fi Eight in-building dining options Signage available in nine languages - English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Hours of Operation From August: Daily - 11AM-11PM Closings & Holidays Open 365 days a year. Getting There Address 20 West 34th Street (between 5th & 6th Avenue) New York, NY 10118 US Closest Subway Stop 6 train to 33rd Street; R, N, Q, B, D, M, F trains to 34th Street/Herald Square; 1, 2, or 3 trains to 34th Street/Penn Station. The Empire State Building is walking distance from Penn Station, Herald Square, Grand Central Station, and Times Square, less than one block from 34th St subway stop. Top of the Rock Observatory Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Getting In: Use the Rockefeller Plaza entrance on 50th Street (between 5th and 6th Avenues).