The University of Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating an Osage Future: Art, Resistance, and Self-Representation

CREATING AN OSAGE FUTURE: ART, RESISTANCE, AND SELF-REPRESENTATION Jami C. Powell A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Jean Dennison Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld Valerie Lambert Jenny Tone-Pah-Hote Chip Colwell © 2018 Jami C. Powell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jami C. Powell: Creating an Osage Future: Art, Resistance, and Self-Representation (Under the direction of Jean Dennison and Rudolf Colloredo Mansfeld) Creating an Osage Future: Art, Resistance, and Self-Representation, examines the ways Osage citizens—and particularly artists—engage with mainstream audiences in museums and other spaces in order to negotiate, manipulate, subvert, and sometimes sustain static notions of Indigeneity. This project interrogates some of the tactics Osage and other American Indian artists are using to imagine a stronger future, as well as the strategies mainstream museums are using to build and sustain more equitable and mutually beneficial relationships between their institutions and Indigenous communities. In addition to object-centered ethnographic research with contemporary Osage artists and Osage citizens and collections-based museum research at various museums, this dissertation is informed by three recent exhibitions featuring the work of Osage artists at the Denver Art Museum, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the Sam Noble Museum at the University of Oklahoma. Drawing on methodologies of humor, autoethnography, and collaborative knowledge-production, this project strives to disrupt the hierarchal structures within academia and museums, opening space for Indigenous and aesthetic knowledges. -

Oral History Interview with Anita Fields

Oral History Interview with Anita Fields Interview Conducted by Julie Pearson-Little Thunder February 14, 2011 Spotlighting Oklahoma Oral History Project Oklahoma Oral History Research Program Edmon Low Library ● Oklahoma State University © 2011 Spotlighting Oklahoma Oral History Project Interview History Interviewer: Julie Pearson-Little Thunder Transcriber: Ashley Sarchet Editors: Julie Pearson-Little Thunder, Latasha Wilson The recording and transcript of this interview were processed at the Oklahoma State University Library in Stillwater, Oklahoma. Project Detail The purpose of the Spotlighting Oklahoma Oral History Project is to document the development of the state by recording its cultural and intellectual history. This project was approved by the Oklahoma State University Institutional Review Board on April 15, 2009. Legal Status Scholarly use of the recordings and transcripts of the interview with Anita Fields is unrestricted. The interview agreement was signed on February 14, 2011. 2 Spotlighting Oklahoma Oral History Project About Anita Fields… Born in Hominy, Oklahoma, earthenware artist Anita Fields spent many of her growing up years in Denver, Colorado. Her early interest in three-dimensional media expressed itself in sewing, making clothes for her favorite doll. After high school, Fields attended the Institute of American Indian Art, where she experimented in multiple media, including painting. However, once she started her family, she put her art aside, and only when her children entered school full-time did she seriously launch her art career. She studied ceramics with Richard Bevins at Oklahoma State University, and soon found her specialty: creating non- functional earthenware. Soon she was winning awards and attention for her clay translations of parfleche bags and buckskin dresses. -

American Indian Graffiti Muralism: Survivance and Geosemiotic Signposts in the American Cityscape

American Indian Graffiti Muralism: Survivance and Geosemiotic Signposts in the American Cityscape Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Healey, Gavin A. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 20:40:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/613132 AMERICAN INDIAN GRAFFITI MURALISM: SURVIVANCE AND GEOSEMIOTIC SIGNPOSTS IN THE AMERICAN CITYSCAPE By Gavin A. Healey __________________________ Copyright © Gavin A. Healey 2016 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDICIPLINARY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Gavin A. Healey, titled American Indian Graffiti Muralism: Survivance and Geosemiotic Signposts in the American Cityscape and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/8/2016) Ronald Trosper _______________________________________________________________________ -

Program at a Glance, 7 Helpful Information, 9 Primary Focus Areas

GATHERING FROM FO UR DIRECTIONS International Conference of Indigenous Archives, Libraries, and Museums NOVEMBER 29-DECEMBER 1, 2021 WASHINGTON, DC INTERESTED IN WORKING WITH NATIVE AMERICAN COLLECTIONS? A PPLY F O R A 2022 ANNE RAY INTERNSHIP The Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, NM, offers two nine-month paid internships to college graduates or junior museum professionals. Internships include a salary, housing, book allowance, travel to one professional conference, and reimbursable travel to and from SAR. Interns participate in the daily activities relating to collections management, registration, education, as well as curatorial training. The IARC works with interns to achieve individual professional goals relating to indigenous cultural preservation in addition to providing broad-based training in the field of museology. APPLICATION DEADLINE: MARCH 1 Learn more and apply: internships.sarweb.org Call 505-954-7205 | Visit sarweb.org | Email [email protected] EXPLORING HUMANITY. UNDERSTANDING OUR WORLD. International Conference of Indigenous Archives, Libraries, and Museums GATHERING FROM FOUR DIRECTIONS November 29-December 1, 2021 Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE COLOR CODES To help you more easily locate the sessions that About the ATALM 2021 Artist and Artwork, 3 relate to your interests, sessions are color coded by primary focus area and than a secondary topic. The Schedule, 5 secondary topics correspond with the 10 Professional Development Certificates offered. Program -

Young Osage Singer Wows Crowd at Good Morning America Studio Shannon Shaw Duty Osage News

Battle of the Plains PAGE 13 Volume 14, Issue 2 • February 2018 The Official Newspaper of the Osage Nation Imperative Entertainment executives honored Stillwater and overwhelmed by Osage tour and culture Public Library to Imperative and wanted to Standing Bear: set up a meeting. After the initial contact was showcasing ‘they want to make made, Principal Chief Geof- a movie the Osage frey Standing Bear appoint- “Killers of the ed Renfro and Roanhorse as will be proud of’ ambassadors for the Nation to spearhead the relationship Flower Moon” Shannon Shaw Duty between the two entities. It Osage News wasn’t until Renfro and Roan- horse attended a meeting with with Osage If there was one conversa- Standing Bear at the Okla- tion that Addie Roanhorse re- homa Film and Music Office events and members from a recent visit in Oklahoma City that they by Imperative Entertainment learned there had been a lack executives is that they want of communication between discussions to make a film that tells the the office and Imperative and Osage story, that tells Mollie as a result Osage County had Osage News Burkhart’s story and showcas- not been named as a possible The Stillwater Public es her as the heroine. film site. Upon learning about Library is hosting a series “We showed them as much the situation Renfro reached of events titled One Book, as we possibly could in a short out to Imperative again and One Community: “Killers arranged for them to visit amount of time,” Roanhorse of the Flower Moon: The the Osage. -

Linda Lomahaftewa

PROFILE LINDA LOMAHAFTEWA to painting and began working in oils. Astonishingly, Hopi Spirits and Unknown Spirits are two of her first paintings, HOPI/CHOCTAW PRINTMAKER AND PAINTER completed when she was only 18 years old. They each express her connection to place through absence and presence. LINDA LOMAHAFTEWA An abstract vision of Hopi spirits gaze from an intimate distance outward and By Jean Merz-Edwards amplify Lomahaftewa’s absence from her home in Arizona. In contrast, a distant “For decades Linda has been a promi- Lomahaftewa, in the spring of 1961, “I got view of mountains—much like the Sangre nent figure in contemporary Native art. a phone call from my mom, and she read de Cristo Mountains visible from Santa Her paintings demonstrate a wonderful in the paper that they would be opening Fe—solidify Lomahaftewa’s presence in a strength informed by her culture placed up this new Indian art school in Santa Fe, place with unknown spirits. Finally, they in a contemporary context.”1 and it’ll be headed up by Lloyd New, who denote the starting point of a journey —Joe Feddersen (Okanagan/Sinixt) was one of her teachers when she went centering Lomahaftewa within the story [to the] Phoenix Indian School.”3 That of Native American art. PPORTUNITY RARELY summer Lomahaftewa and her mother AFFORDS us the benefit of filled out the application. In the fall of CALIFORNIA DAYS visiting with a living legend. 1962, Lomahaftewa began her sophomore “I WAS TAUGHT to believe in myself, Whether it be the scarcity O year in the first high school class at the that’s how I grew up,” Lomahaftewa of such individuals or our proximity to Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). -

Haway) Northern California (Osage

(HAWAY) NORTHERN CALIFORNIA (OSAGE) What: Fall Northern California Osage gathering The Northern California Osage group was formed by When: Saturday, November 2nd 10am-7pm Osages living in northern California to meet for fellowship. The Northern California Osages are not affiliated with any Where: Leona Lodge, 4444 Mountain Blvd, Oakland past northern California Osage organization or any other CA current Osage organization. We do not hold a political RSVP: [email protected] or mail agenda nor do we endorse any political candidate or issue. to Karen Elliott (address below) The group’s sole purpose is to provide a meeting space for Lunch & Dinner: Potluck, please bring a dish if the sharing of cultural values and ideas including issues of possible concern about the Osage Nation. We usually organize two meetings a year (spring & fall) hosting a diversity of guests Nearby Camping: Anthony Chabot Regional Park from Oklahoma. 1-888-327-2757 Agenda *Membership dues and the raffle help to pay mailing and printing costs, and supplement Introductions gathering and food expenses. Seed Preservation Project Update- Keir Johnson Julie O’Keefe, Board Member of the Osage Nation Have an item to donate to the raffle? Foundation will give a talk about the foundation & arts Bring it with you to the meeting! matching grants Writer, lecturer & poet Duane BigEagle will read from selected works and hold an optional creative writing workshop Writer & photographer Ruby Hansen Murray will read from selected works and hold an optional writing workshop "Loving Place" Yatika Starr Fields Artist Talk Live painting performance by Yatika Fields to the music of Marca Cassity & George Baldwin Artists Yatika Starr Fields, Caroll Loomis, Melani King, Cindy Douglass, and other participating artists showing and selling works throughout the day Chief John D. -

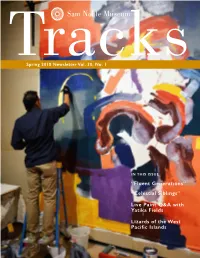

Fluent Generations” “Celestial Siblings”

TracksSpring 2018 Newsletter Vol. 30, No. 1 IN THIS ISSUE “Fluent Generations” “Celestial Siblings” Live Paint Q&A with Yatika Fields Lizards of the West Pacific Islands Contents generations FluentThe Art of Anita, Tom and Yatika Fields Fluent Generations 4 Exhibition Catalog Available in Excavations the Museum Store 10 $19.95 4 8 13 14 sam noble oklahoma museum of natural history • university of oklahoma FEATURES AND DEPARTMENTS 4 FROM THE DIRECTOR 12 NEWS TRACKS, SPRING 2018 VOLUME 30, NO. 1 Thirty Years at the Helm 2018 Volunteer of the Year 8 EXHIBITION 13 NEWS MUSEUM INFORMATION OUR MISSION TRACKS “Fluent Generations: The Art of Anita, Tom Research Doubles Native Mammal Species Address The Sam Noble Museum at the Editor-in-Chief: Michael A. Mares and Yatika Fields” in Hawaii Sam Noble Museum University of Oklahoma inspires Managing Editor: Pam McIntosh The University of Oklahoma minds to understand the world Associate Editor: Hannah Pike 9 EXHIBITION 14 NEWS 2401 Chautauqua Ave. through collection-based research, “Celestial Siblings: Parallel Landscapes of Earth Lizards of the West Pacific Islands Norman, OK 73072-7029 interpretation and education. This publication is printed on paper and Mars containing 30 percent post consumer ON THE FRONT COVER: Telephone: (405) 325-4712 OUR VISION recycled fiber. Please recycle. 10 NEWS Yatika Fields painting mural in Brown Gallery. Photo by As one of the finest museums, we are at Live Paint Q&A with Yatika Fields Hannah Pike Email: [email protected] This publication, printed by the Sam Noble the heart of our community, collectively ON THE BACK COVER: Museum, is issued by the University of Oklahoma. -

Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum Featuring Tulsa Native American Family in Exhibit ‘Fluent Generations: the Art of Anita, Tom and Yatika Fields’

Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum featuring Tulsa Native American family in exhibit ‘Fluent Generations: The Art of Anita, Tom and Yatika Fields’ BY BRANDY MCDONNELL JANUARY 18, 2018 A family of accomplished Native American artists will showcase their works of photography, ceramics and paintings, celebrating the vitality of indigenous cultures, in the newest exhibit to be unveiled this month at the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. In “Fluent Generations: The Art of Anita, Tom and Yatika Fields,” Anita Fields (Osage), along with husband Tom Fields (Muscogee, Cherokee) and son Yatika Starr Fields (Osage, Muscogee, Cherokee), come together for the first time ever to illustrate their creativity and passion under one roof, with works hat bring their cultural heritage to life inside the Sam Noble Museum. “Fluent Generations,” will be located in the museum’s first-floor Fred and Enid Brown gallery, is sponsored by Fowler Automotive and Jones PR Inc. and on display Saturday through May 6. The exhibit features a number of never-before-seen pieces of artwork by the Tulsa-based family, whose works have been exhibited nationally and internationally, according to a news releas.e The exhibit also features loans from the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, Oklahoma State University Yatika Fields’ (Osage/Muscogee/Cherokee) acrylic on canvas painting “Renewal” Museum of Art, the Arkansas Heritage Museum, private collections and the artists’ own collections. Museum visitors will get the opportunity to not only develop a keen appreciation for the work of the Fields family, but a deeper appreciation for the impact of family — a building block of all cultures and communities around the world, said Dan Swan, exhibit curator and curator of ethnology at the Sam Noble Museum. -

Contemporary Native American Art

CONTEMPORARY NATIVE AMERICAN ART YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji YegÓji Newspapers for this educational program provided by: teacher’s guide 1 about these ancient traditions that he American Indian Cultural Center and Museum (AICCM) is T are based on the identity, talent and honored to present, in partnership in with Newspapers in Education at creativity that continues to astound The Oklahoman, the Native American Heritage educational workbook. The and inspire us today. Native American Heritage educational programs focus on the cultures, histories and governments of the American Indian tribes of Oklahoma. – Gena Timberman, Esq., The programs are published twice a year, in the Fall and Spring Director of The Native American semesters. Each workbook is organized into four core thematic areas: Cultural Center and Museum Origins, Native Knowledge, Community and Governance. Because it is impossible to cover every aspect of the topics featured in each edition, the Border Art (above) workbooks will comprehensively introduce students to a variety of new Southern Plains subjects and ideas. We hope you will be inspired to research and find –by Yatika Starr Fields, out more information with the help of teachers and parents, as well as Osage/Muscogee Creek/Cherokee through your own independent research. Special thanks goes to the following program partners for contributing About the Cover to the content of this publication: Interface Protocol (21st Century • Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art Ledger Drawing #36), pencil on • Gilcrease Museum antique ledger paper • Denver Art Museum Chris Pappan, Kaw/Osage/ Bunky Echo-Hawk “Napoleon Dynomite“ • Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art Cheyenne River Sioux (Pawnee/Yakama) • Five Civilized Tribes Museum The two figures or “mirrored” images Ben Harjo “Live in Balance” (Muscogee Creek) • Oklahoma Arts Council represent two people or two ideas coming together to create something new.