Prajnaparamita -Sutra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

Guenther's Saraha: a Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity 111 ROGER JACKSON

J ournal of the international Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 17 • Number 1 • Summer 1994 HUGH B. URBAN and PAUL J. GRIFFITHS What Else Remains in Sunyata? An Investigation of Terms for Mental Imagery in the Madhyantavibhaga-Corpus 1 BROOK ZIPORYN Anti-Chan Polemics in Post Tang Tiantai 26 DING-HWA EVELYN HSIEH Yuan-wu K'o-ch'in's (1063-1135) Teaching of Ch'an Kung-an Practice: A Transition from the Literary Study of Ch'an Kung-an to the Practical JCan-hua Ch'an 66 ALLAN A. ANDREWS Honen and Popular Pure Land Piety: Assimilation and Transformation 96 ROGER JACKSON Guenther's Saraha: A Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity 111 ROGER JACKSON Guenther's Saraha: A Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity Herbert Guenther. Ecstatic Spontaneity: Saraha's Three Cycles of Doha. Nanzan Studies in Asian Religions 4. Berkeley: Asian Humani ties Press, 1993. xvi + 241 pages. Saraha and His Scholars Saraha is one of the great figures in the history of Indian Mahayana Buddhism. As one of the earliest and certainly the most important of the eighty-four eccentric yogis known as the "great adepts" (mahasiddhas), he is as seminal and radical a figure in the tantric tradition as Nagarjuna is in the tradition of sutra-based Mahayana philosophy.l His corpus of what might (with a nod to Blake) be called "songs of experience," in such forms as the doha, caryagiti and vajragiti, profoundly influenced generations of Indian, and then Tibetan, tantric practitioners and poets, above all those who concerned themselves with experience of Maha- mudra, the "Great Seal," or "Great Symbol," about which Saraha wrote so much. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’S Mentality

International Conference of Electrical, Automation and Mechanical Engineering (EAME 2015) The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’s Mentality X.H. Li School of literature and Journalism Shandong University Jinan China Abstract—In order to study the influence of Buddhism, most of A. Sukhavati: Maitreya and MiTuo the temples and document in china were investigated. The results Hui Yuan and Daolin Zhi also have faith in Sukhavati. indicated that Buddhism developed rapidly in Southern dynasty. Sukhavati is the world where Buddha live. Since there are Along with the translation of Buddhist scriptures, there were lots many Buddha, there are also kinds of Sukhavati. In Southern of theories about Buddhism at that time. The most popular Dynasty the most prevalent is maitreya pure land and MiTuo Buddhist theories were Prajna, Sukhavati and Nirvana. All those theories have important influence on Nan dynasty’s literati, pure land. especially on their mentality. They were quite different from The advocacy of maitreya pure land is Daolin Zhi while literati of former dynasties: their attitude toward death, work Hui Yuan is the supporter of MiTuo pure land. Hui Yuan’s and nature are more broad-minded. All those factors are MiTuo pure land wins for its simple practice and beautiful displayed in their poems. story. According to < Amitabha Sutra>, Sukhavati is a perfect world with wonderful flowers and music, decorated by all Keyword-the evolvement of buddhism; southern dynasty; kinds of jewelry. And it is so easy for every one to enter this literati’s mentality paradise only by chanting Amitabha’s name for seven days[2] . -

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

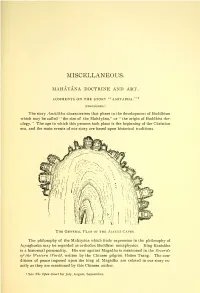

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara

Aspects of Buddhist Psychology Lecture 42: The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara Reverend Sir, and Friends Our course of lectures week by week is proceeding. We have dealt already with the analytical psychology of the Abhidharma; we have dealt also with the psychology of spiritual development. The first lecture, we may say, was concerned mainly with some of the more important themes and technicalities of early Buddhist psychology. We shall, incidentally, be referring back to some of that material more than once in the course of the coming lectures. The second lecture in the course, on the psychology of spiritual development, was concerned much more directly than the first lecture was with the spiritual life. You may remember that we traced the ascent of humanity up the stages of the spiral from the round of existence, from Samsara, even to Nirvana. Today we come to our third lecture, our third subject, which is the Depth Psychology of the Yogacara. This evening we are concerned to some extent with psychological themes and technicalities, as we were in the first lecture, but we're also concerned, as we were in the second lecture, with the spiritual life itself. We are concerned with the first as subordinate to the second, as we shall see in due course. So we may say, broadly speaking, that this evening's lecture follows a sort of middle way, or middle course, between the type of subject matter we had in the first lecture and the type of subject matter we had in the second. Now a question which immediately arises, and which must have occurred to most of you when the title of the lecture was announced, "What is the Yogacara?" I'm sorry that in the course of the lectures we keep on having to have all these Sanskrit and Pali names and titles and so on, but until they become as it were naturalised in English, there's no other way. -

The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra (2Nd Edition)

TheThe PrajnaPrajna ParamitaParamita HeartHeart SutraSutra Translated by Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary by Grand Master T'an Hsu English Translation by Ven. Master Lok To Second Edition 2000 HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra Translated from Sanskrit into Chinese By Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary By Grand Master T’an Hsu Translated Into English By Venerable Dharma Master Lok To Edited by K’un Li, Shih and Dr. Frank G. French Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada New York – San Francisco – Toronto 2000 First published 1995 Second Edition 2000 Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada Dharma Master Lok To, Director 2611 Davidson Ave. Bronx, New York 10468 (USA) Tel. (718) 584-0621 2 Other Works by the Committee: 1. The Buddhist Liturgy 2. The Sutra of Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha’s Fundamental Vows 3. The Dharma of Mind Transmission 4. The Practice of Bodhisattva Dharma 5. An Exhortation to Be Alert to the Dharma 6. A Composition Urging the Generation of the Bodhi Mind 7. Practice and Attain Sudden Enlightenment 8. Pure Land Buddhism: Dialogues with Ancient Masters 9. Pure-Land Zen, Zen Pure-Land 10. Pure Land of the Patriarchs 11. Horizontal Escape: Pure Land Buddhism in Theory & Practice. 12. Mind Transmission Seals 13. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra 14. Pure Land, Pure Mind 15. Bouddhisme, Sagesse et Foi 16. Entering the Tao of Sudden Enlightenment 17. The Direct Approach to Buddhadharma 18. -

Diamond Sutra) 『菩薩於法,應無所住,行於布施

Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas Sponsored By Pure Land Center & Buddhist LiBrary 1120 E. Ogden Avenue, Suite 108 Naperville, IL 60563 http://www.amitabhalibrary.org Tel: (630) 428-9941; Fax: (630) 428-9961 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 1 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic One : The Basics èBuddhism is an education, not a religion or a philosophy n It teaches us how to recover our wisdom and regain our Buddha nature n It teaches us how to solve our proBlems through wisdom – an art of living èThe Law of Causality governs everything in the universe èAll sentient Beings possess the same Buddha nature n Our Buddha nature is temporarily lost due to delusion n Our lost Buddha nature can be recovered only via cultivation èKarma refers to an action and its retriBution under the Law of Causality n Good and bad karmas do not offset each other – prevailing ones occur first n Karmas, good or Bad, accumulate over time and do not disappear n When many Bad karmic retriButions come together, they form disasters èCultivation means to stop planting Bad seeds and nurturing Bad conditions, and to, instead, plant good seeds and nurture good conditions Last updated Nov. 2016 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 2 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic Two : The Three Refuges and the Four Reliance -

A Lamp Illuminating the Path to Liberation 2Nd

A Lamp Illuminating the Path to Liberation An Explanation of Essential Topics for Dharma Students By Khenpo Gyaltsen Translated by Lhasey Lotsawa Translations ❁ A Lamp Illuminating the Path to Liberation An Explanation of Essential Topics for Dharma Students By Khenpo Gyaltsen ❁ Contents Foreword i 1. The Reasons for Practicing Buddhadharma 1 2. The Benefits of Practicing the Buddhadharma 4 3. The Way the Teacher Expounds the Dharma 7 4. The Way the Student Listens to the Dharma 10 5. Faith ~ the Root of All Dharma 16 6. Refuge ~ the Gateway to the Doctrine 20 7. Compassion ~ the Essence of the Path 34 8. The Four Seals ~ the Hallmark of the 39 Buddhadharma and the Essence of the Path 9. A Brief Explanation of Cause & Effect 54 10. The Ethics of the Ten Virtues and Ten Non-virtues 58 11. The Difference Between the One-day Vow and the 62 Fasting Vow 12. The Benefits of Constructing the Three 68 Representations of Enlightened Body, Speech, and Mind 13. How to Make Mandala Offerings to Gather the 74 Accumulations, and their Benefits 14. How to Make Water Offerings, and their Benefits 86 15. Butter Lamp Offerings and their Benefits 93 16. The Benefits of Offering Things such as Parasols 98 and Flowers 17. The Method of Prostrating and its Benefits 106 18. How to Make Circumambulations and their 114 Benefits 19. The Dharani Mantra of Buddha Shakyamuni: How 121 to Visualize and its Benefits 20. The Stages of Visualization of the Mani Mantra, 127 and its Benefits 21. The Significance of the Mani Wheel 133 22. -

The Heart of Prajnaparamita

The Heart of the Prajna Paramita Sutra http://www.io.com/~snewton/zen/heartsut.html Portland Zen Community Primary Zen Texts The Wider Zen Sangha Books to Read Random Thoughts Search these Texts Zen Buddhist Texts Home The free seeing Bodhisattva of compassion, while in profound contemplation of Prajna Paramita, beheld five skandhas as empty in their being and thus crossed over all sufferings. O-oh Sariputra, what is seen does not differ from what is empty, nor does what is empty differ from what is seen; what is seen is empty, what is empty is seen. It is the same for sense perception, imagination, mental function and judgement. O-oh Sariputra, all the empty forms of these dharmas neither come to be nor pass away and are not created or annihilated, not impure or pure, and cannot be increased or decreased. Since in emptiness nothing can be seen, there is no perception, imagination, mental function or judgement. There is no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body or consciousness. Nor are there sights, sounds, odors, tastes, objects or dharmas. There is no visual world, world of consciousness or other world. There is no ignorance or extinction of ignorance and so forth down to no aging and death and also no extinction of aging and death. There is neither suffering, causation, annihilation nor path. There is no knowing or unknowing. Since nothing can be known, Bodhisattvas rely upon Prajna Paramita and so their minds are unhindered. Because there is no hindrance, no fear exists and they are far from inverted and illusory thought and thereby attain nirvana. -

Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and Its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 8, No. 1; 2016 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism Xican Li1 1 School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China Correspondence: Xican Li, School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center, 510006, Guangzhou, China. Tel: 86-203-935-8076. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 21, 2015 Accepted: August 31, 2015 Online Published: September 2, 2015 doi:10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 Abstract Guangxiao Temple is located in Guangzhou (a coastal city in Southern China), and has a long history. The present study conducted an onsite investigation of Guangxiao’s precious Buddhist relics, and combined this with a textual analysis of Annals of Guangxiao Temple, to discuss its history and multi-roles in Asia-Pacific Buddhism. It is argued that Guangxiao’s 1,700-year history can be seen as a microcosm of Chinese Buddhist history. As the special geographical position, Guangxiao Temple often acted as a stopover point for Asian missionary monks in the past. It also played a central role in propagating various elements of Buddhism, including precepts school, Chan (Zen), esoteric (Shingon) Buddhism, and Pure Land. Particulary, Huineng, the sixth Chinese patriarch of Chan Buddhism, made his first public Chan lecture and was tonsured in Guangxiao Temple; Esoteric Buddhist master Amoghavajra’s first teaching of esoteric Buddhism is thought to have been in Guangxiao Temple.