A Unified Patent for Europe and a Unified Way of Enforcing It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Patent Convention and the London Agreement

Feature European changes The European Patent Convention and the London Agreement EPC 2000 – why change? By Pierre-André Dubois and Shannon The EPC 1973 came into force in 1977 and Yavorsky, Kirkland & Ellis International LLP revolutionised patent practice. However, in the last 30 years, the patent landscape The European Patent Convention (EPC 2000) changed significantly and it became apparent came into force on 13th December 2007, that there was a real need to overhaul the introducing sweeping changes to the dated legislation. First, the Agreement on European patent system. The new Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual convention governs the granting of European Property Rights (TRIPs) and the Patent Law patents by the European Patent Office (EPO) Treaty (PLT) came into force, and it was and applies throughout the 34 contracting questionable whether the EPC 1973 was in states of the European Patent Organisation line with the provisions of each of these (ie, the 27 EU Member States as well as agreements. As one example, the EPC 2000 Croatia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Monaco, clarifies that, in accordance with TRIPs, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey). The original patents can now be granted in all fields of convention (EPC 1973), which dates back to technology as long as they are new, 1973, was outdated due to a number of comprise an inventive step and are developments in international law and the susceptible of industrial application. Second, need to improve the procedure before the the EPC 1973 was difficult to amend and, in EPO. While the new convention does not the face of fast-changing technology and overhaul substantive patent law (ie, what European legislation, required greater is patentable and what is not), it does legislative flexibility. -

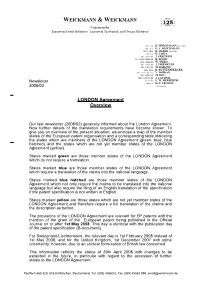

WEICKMANN & WEICKMANN LONDON Agreement Overview

1 YEARS 2 WEICKMANN & WEICKMANN 8 0 8 0 125JAHRE Patentanwälte 2 7 European Patent Attorneys · European Trademark and Design Attorneys DIPL.-ING. H. WEICKMANN (bis 2001) DIPL.-ING. F. A. WEICKMANN DIPL.-CHEM. B. HUBER (bis 2006) DR.-ING. H. LISKA DIPL.-PHYS. DR. J. PRECHTEL LL.M. DIPL.-CHEM. DR. B. BÖHM DIPL.-CHEM. DR. W. WEISS DIPL.-PHYS. DR. J. TIESMEYER DIPL.-PHYS. DR. M. HERZOG DIPL.-PHYS. B. RUTTENSPERGER DIPL.-PHYS. DR.-ING. V. JORDAN DIPL.-CHEM. DR. M. DEY DIPL.-FORSTW. DR. J. LACHNIT Newsletter LL.M. DR. U. W. HERBERTH * DR.-ING. H.-J. TROSSIN 2008/03 * Rechtsanwalt LONDON Agreement Overview Our last newsletter (2008/02) generally informed about the London Agreement. Now further details of the translation requirements have become known. To give you an overview of the present situation, we enclose a map of the member states of the European patent organisation and a corresponding table indicating the states which are members of the LONDON Agreement (green, blue, blue hatched) and the states which are not yet member states of the LONDON Agreement (yellow). States marked green are those member states of the LONDON Agreement which do not require a translation. States marked blue are those member states of the LONDON Agreement which require a translation of the claims into the national language. States marked blue hatched are those member states of the LONDON Agreement which not only require the claims to be translated into the national language but also require the filing of an English translation of the specification if the patent specification is not written in English. -

The Road Towards a European Unitary Patent

EUC Working Paper No. 21 Working Paper No. 21, March 2014 Unified European Front: The Road towards a European Unitary Patent Gaurav Jit Singh Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore Photo: BNEGroup.org ABSTRACT For over forty years, European countries have held numerous conferences and signed multiple international agreements aimed at either creating a unitary patent which will be valid in all European countries upon issuance or establishing a specialized European court with jurisdiction over patents. This paper first outlines the need for a unitary patent in the European Union and then chronicles the measures taken to support and milestones toward the creation of a European-wide unitary patent system. The paper then discusses the few problems and pitfalls that have prevented European countries from coming to an agreement on such a patent system. Finally, the paper considers the closely related agreements of ‘Unitary Patent Package’, the challenges facing these agreements and examines if it would finally result in an EU Unitary patent system that benefits one and all. The views expressed in this working paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union or the EU Centre in Singapore. The EU Centre in Singapore is a partnership of 13 EUC Working Paper No. 21 UNIFIED EUROPEAN FRONT: THE ROAD TOWARDS A EUROPEAN UNITARY PATENT GAURAV JIT SINGH1 INTRODUCTION Obtaining, enforcing and maintaining patents in the EU are far from efficient or cost effective. An inventor that seeks patent protection in the European Union (EU) territory now has to either file for a national patent in each one of 28 national patent offices, or file for a European patent, granted by the European Patent Office (EPO), within the framework of the European Patent Convention (EPC)2. -

Germany, Reparation Commission)

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Interpretation of London Agreement of August 9, 1924 (Germany, Reparation Commission) 24 March 1926, 29 January 1927, 29 May 1928 VOLUME II pp. 873-899 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2006 XXI a. INTERPRETATION OF LONDON "AGREEMENT OF AUGUST 9, 1924 *. PARTIES: Germany and Reparation Commission. SPECIAL AGREEMENT: Terms of submission contained in letter signed by Parties in Paris on August 28, 1925, in conformity with London Agree- ment of August 9, 1924. ARBITRATORS: Walter P. Cook (U.S.A.), President, Marc. Wallen- berg (Sweden), A. G. Kroller (Netherlands), Charles Rist (France), A. Mendelssohn Bartholdy (Germany). AWARD: The Hague, March 24, 1926. Social insurance funds in Alsace-Lorraine.—Social insurance funds in Upper Silesia.—Intention of a provision as a principle of interpretation.— Experts' report and countries not having accepted the report.—Baden Agreement of March 3, 1920.—Restitution in specie.—Spirit of a treaty.— Supply of coal to the S.S. Jupiter.—Transaction of private character. For bibliography, index and tables, see Volume III. 875 Special Agreement. AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE REPARATION COMMISSION AND THE GERMAN GOVERNMENT. Signed at London. August 9th, 1924. Ill (b) Any dispute which may arise between the Reparation Commission and the German Government with regard to the interpretation either of the present agreement and its schedules or of the experts' plan or of the •German legislation enacted in execution of that plan, shall be submitted to arbitration in accordance with the methods to be fixed and subject to the conditions to be determined by the London conference for questions of the interpretation of the experts' Dlan. -

EPC 2000 the Revised European Patent Convention + the London Agreement

EPC 2000 The Revised European Patent Convention + The London Agreement 2nd edition Königstraße 70 Am Literaturhaus 90402 Nürnberg Telefon: (0911) 89138-0 Telefax: (0911) 89138-29 Am Stein 12 D-97080 Würzburg Telefon: (0931) 286410 Telefax: (0931) 282597 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.ip-goetz.eu 1 What is the EPC? A multilateral treaty (34 contracting states) for a centralised patent grant procedure before a single patent office (EPO). To modernize the European patent system and adapt it to TRIPS (Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) and PLT (Patent Law Treaty), the revised EPC 2000 has entered into force on 12/13/2007. 2 What is the London Agreement? A multilateral sub-treaty (14 contracting states) to the EPC for the purpose to save translation costs (see at the end). 3 EPC 2000: Highlights at first glance (I) Changes in substantive patent law ➔ inventions in „all fields of technology“ (adaptation to TRIPS) no substantial change of current practise ➔ use-limited product protection for a second or further medical use of a kown substance (see example below) ➔ novelty-destroying effect of subsequently published EP application having an earlier priority date independent of country designation (see examples below) ➔ strengthening of extent of protection (see below) 4 EPC 2000: Highlights at first glance (II) Procedural „innovations“: ➔ Drastically decreasing requirements for the filing date (adaptation to PLT – see below) ➔ Re-establishment of rights and corrections in respect of priority claim ➔ Further processing of an application as standard legal remedy in respect of observing time limits ➔ Request by patent owner for centralised limitation or revocation of the EP patent ➔ Introduction of a third instance (Enlarged Board of Appeal) for the case of fundamental procedural defects in appeal proceedings (e.g. -

The London Agreement

Intellectual Property PATENTS PATENTS The London Agreement The London Agreement is a voluntary agreement to which individual countries within the European patent system sign up as and when they want to. There are two groups of countries – a first group which have a local language which is one of the EPO languages of use (i.e. English, French or German) and a second group which has a non-EPO language as their language of use. For the first group of countries – those countries which have signed the London Agreement and which work in any of the three languages of the EPO - any translation requirement post-grant is prohibited. These countries are: UK Luxembourg Germany Liechtenstein France Monaco Switzerland The second group of countries, which do not have as one of their official languages an EPO language, are entitled to a translation of at least the claims into one of their own languages, and they can, if they want to, prescribe a language (of the EPO three official languages) into which the description that precedes the claims shall be translated. Of countries in the second group, some have specified that the text should be in English. Some do not mind what language (so long as it is one of the three EPO languages). So far as we are aware, no-one has specified French or German. Those countries in this second group, who have subscribed to the London Agreement, are: Croatia Netherlands Denmark Latvia Iceland Slovenia Sweden Finland (from 1 November 2011) Hungary So for these countries, only the claims needs to be translated and the rest of the text can be in English. -

European Patent Procedure Explained

European Patent Procedure Explained Patents in Europe When protecting an invention in Europe, you can either file a single European patent application covering 40 member states, or you can file individual national patent applications in each separate European state where you require patent protection. In general, if you require patent protection in more than a single national European state, it is likely to be more cost effective to file a European patent application under the European Patent Convention. European patent applications can take quite a long time to process. The average prosecution from filing to a decision on grant is around 44 months. Prosecution can be quicker in some individual national states. This is particularly true in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Additionally, short term patents (known as petty patents, or utility models), where there is generally a novelty requirement and either no inventive step requirement, or a lower level of inventive step requirement than for a European patent or a standard national patent, are available in some European states, for example Germany and Italy. These may have a cost or speed advantage over a standard national patent, or a European patent. However, for most inventions originating outside Europe, the European patent under the European Patent Convention, is the primary form of protection. European Patent - Overall Procedure From filing to grant, the stages are: - Filing the application: A full description, claims, abstract and where appropriate drawings, must be supplied at the point of filing. An application fee and search fee are also due on filing. The application can be filed in any official language of a member state, but a translation into English, French or German, the three official languages of the European Patent Convention, must be supplied shortly after filing. -

A Unitary Patent for Europe and a Unified Way of Enforcing It: an Update – September 2012

A UNITARY PATENT FOR EUROPE AND A UNIFIED WAY OF ENFORCING IT: AN UPDAte – SePTEMBER 2012 Introduction Once a patent has been successfully validated in a particular country to keep it in force renewal fees have to be paid This review article firstly looks at the current state of play in annually. If these are not paid then the patent lapses. The terms of obtaining and enforcing patents in Europe. It then level of renewal fees varies considerably across the EU. The outlines the changes which are proposed in terms of the deadlines for payment differ between different countries. In unitary patent and the unified patents court and sets out where some countries payment of renewal fees is still not possible by the legislative process has got to in relation to those changes. bank transfer. Finally some countries mandate the appointment of a patent attorney to deal with renewals and require all communications to them to be in their local language. The European Patent Convention A consequence of these costs is that the average EPC patent application is now validated in only five countries5. The European Union currently has 27 member countries. To These problems have long been recognised however and protect their inventions in this market of more than 500 million one practical step taken to address them was the London people, business has had no alternative other than to obtain Agreement. 27 separate national patents, one for each European country, and then to enforce them separately on a country by country basis. In China, India and the US by contrast single patents cover populations of 1.34 billion, 1.2 billion and 312 million The London Agreement respectively. -

Patent Practice in London

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 2 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2004 2004 Patent Practice in London - Local Internationalism: How Patent Law Magnifies the Relationship of the United Kingdom with Europe, the United States, and the Rest of the World Thomas K. McBride Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas K. McBride Jr. Patent Practice in London - Local Internationalism: How Patent Law Magnifies the Relationship of the United Kingdom with Europe, the United States, and the Rest of the World, 2 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 31 (2004). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol2/iss1/3 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PATENT PRACTICE IN LONDON - LOCAL INTERNATIONALISM: How PATENT LAW MAGNIFIES THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE UNITED KINGDOM WITH EUROPE, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE REST OF THE WORLD Thomas K. McBride, Jr.* I. Patent Law Basics ............................................. 33 A. European Patent Convention for Patent Issuance ............ 36 B. Retained National Law for Infringement and Licensing ...... 38 1. Conflicts Between U.K. and Germany .................. 40 2. Conflicts Between U.K. and EPC ...................... 43 C. Other Issues in Patent Law: Italian Torpedoes and T R IP s .................................................... 45 II. British Patent Systems and Practice ............................ 47 A. Patent Attorneys, Solicitors, and Barristers .................. 47 B. Special Courts in Chancery ............................... -

Michalski Hüttermann & Partner

M I C H A L S K I · H Ü T T E R M A N N & P A R T N E R Recent Changes in European Patent Regulations Dr. Dirk Schulz Recent changes in European Patent Regulations The EPC in the past London Agreement EPC 2000 Subsequent amendments of the ancillary regulations M I C H A L S K I H Ü T T E R M A N N P A T E N T A T T O R N E Y S The EPC: A Success Story - Introduced in 1973 as a trilangual system - Today: 34 member states - One international authority responsible for „national“ patents - Excellent standard of examination - Average duration until grant: 3.5 years - Highly efficient post grant oppostion system - Case law system with boards of appeal and enlarged board of appeal predictable jurisdiction - Blueprint for other regions: Eurasia (EAPO), Africa (ARIPO, OAPI) M I C H A L S K I H Ü T T E R M A N N P A T E N T A T T O R N E Y S M I C H A L S K I H Ü T T E R M A N N P A T E N T A T T O R N E Y S Drawback: High Official Fees and Translation Costs Costs until grant Market size Costs for first (official fees and level infringement translation) suit Europe 11,000 € 230 millions 50,000 € (refund) USA 2,500 € 305 millions 750,000 € Japan 2,000 € 127 millions n/a Europe: Validation in 6 states including Italy and Spain „Compensation“ by affordable and predictable patent jurisdiction lower attorney‘s fees M I C H A L S K I H Ü T T E R M A N N P A T E N T A T T O R N E Y S London Agreement Waiver of post-grant patent translation requirement Entered info force on May 1, 2008 Applicable for applications submitted before May 1, 2008 22-page -

EPO: Main Features and News of the European Patent System Your Idea Our Experience 27.04.2010

EPO: Main Features and News of the European Patent System Your idea our experience 27.04.2010 Overview: • The European Patent Organization – The European Patent Office – The Administrative Council • The European Patent System – Patentability – Filing/grant procedure –Euro-PCT • Special issues concerning filing of European Applications by non-member states • Important amendments of Implementing Regulations in EPC Structure of the European Patent Organisation European Patent Organisation European Patent Office Administrative Council The executive body The legislative body responsible for made up of delegates examining European from the member Patent Applications states on the basis of bilateral supervises the agreements acting as activities of the Office RO, ISA and IPEA under the Patent Co- has a specific operation Treaty (PCT) legislative function European Patent Office • Filing Offices: – Munich – The Hague – Berlin • Branch Office: – Vienna • www.epo.org 30.04.2010 EPO Organization President Presidential Alison area Brimelow 5 Directorates General: Operational Operations Appeals Administra- Legal/adm. support tion affairs Search Patent administration Boards of Appeal European Patent Academy Examination Enlarged Board Information Services Opposition of Appeal 30.04.2010 36 Contracting States AT Austria LT Lithuania BE Belgium LU Luxembourg BU Bulgaria LV Latvia CH Switzerland MC Monaco CY Cyprus MK FYR Macedonia CZ Czech Republic MT Malta DE Germany NL Netherlands DK Denmark NO Norway EE Estonia PL Poland ES Spain PT Portugal FI Finland RO Romania FR France SE Sweden GB United Kingdom SI Slovenia GR Greece SK Slovakia HR Croatia SM San Marino HU Hungary TR Turkey IE Ireland IS Iceland IT Italy LI Liechtenstein 30.04.2010 Extension States • AL Albania (will become Contracting State 1 May 2010) • RS Serbia • BA Bosnia Herzegovina • ME Montenegro (from 1 March 2010) States having special agreements with the EPO. -

Translation Requirements for Granted European Patents

Translation requirements for granted European Patents Shortly after grant of a European patent, certain formalities are necessary in order to validate the patent in the EPC (European Patent Convention) states of choice (see our information sheet, “Grant stage of European Patents” for further details on grant phase procedure). A significant proportion of the cost to patentees at this stage is due to translation of the text into the local languages of those EPC states in which it is desired to validate the European patent. Since the London Agreement came into force in 2008, Other states, which have acceded to the London the costs incurred by translations have not been as Agreement but do not share a language with the EPO, high as they once were, although the variety of different have nominated a “prescribed language”, i.e. which of translation requirements has made the situation more English, French and German they will accept translations complex. into in order for the patent to be entered into force in that country. To date, all states in this category have chosen English as the prescribed language. This means that filing How the London Agreement works and prosecuting an application in English, rather than European patents are granted in one of the three official French or German, reduces the validation costs in such languages of the EPO, i.e. English, French or German. states. Some of these states only require translations of States which have signed the London Agreement and have the claims into their local language as set out below. one of the EPO languages as an official language, do not require any translation of the text in order for the patent • States which require a translation of the claims to be validated nationally (translations of the claims in all into their local language (but no translation of the three EPO languages are still required prior to grant).