Sustainable Financing of Protected Areas in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon

A Strategic A Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC) UrbanDevelopment Plan of Greater The Republic of the Union of Myanmar A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Yangon FINAL REPORT I Part-I: The Current Conditions FINAL REPORT I FINAL Part - I:The Current Conditions April 2013 Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. NJS Consultants Co., Ltd. YACHIYO Engineering Co., Ltd. International Development Center of Japan Inc. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. 2013 April ALMEC Corporation JICA EI JR 13-132 N 0 300km 0 20km INDIA CHINA Yangon Region BANGLADESH MYANMAR LAOS Taikkyi T.S. Yangon Region Greater Yangon THAILAND Hmawbi T.S. Hlegu T.S. Htantabin T.S. Yangon City Kayan T.S. 20km 30km Twantay T.S. Thanlyin T.S. Thongwa T.S. Thilawa Port & SEZ Planning調査対象地域 Area Kyauktan T.S. Kawhmu T.S. Kungyangon T.S. 調査対象地域Greater Yangon (Yangon City and Periphery 6 Townships) ヤンゴン地域Yangon Region Planning調査対象位置図 Area ヤンゴン市Yangon City The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I The Project for The Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I < Part-I: The Current Conditions > The Final Report I consists of three parts as shown below, and this is Part-I. 1. Part-I: The Current Conditions 2. Part-II: The Master Plan 3. Part-III: Appendix TABLE OF CONTENTS Page < Part-I: The Current Conditions > CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives .................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 Study Period ............................................................................................................. -

Tourism Assessment in Protected Areas

Myanmar Ecotourism Policy and Management Strategy Assessment of Tourism and Conservation Issues in and around 21 National Protected Areas Prioritised for Ecotourism 21 National Protected Areas Prioritised for Ecotourism Figure 1: Myanmar’s 21 Protected Areas Designated for Ecotourism Ecotourism Sites in Myanmar • Myanmar has designated 21 ecotourism sites under the PAS: 1. Hkakaborazi National Park (AHP) 2. Hponkanrazi Wildlife Sanctuary 3. Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary (AHP) 4. Hukaung Valley Wildlife Sanctuary 5. Natmataung National Park (AHP) 6. Kyaikhtiyoe Wildlife Sanctuary 7. Inlay Lake Wildlife Sanctuary (AHP) 8. Panlaung-pyadalin Cave Wildlife Sanctuary 9. Alaungdaw Katthapa National Park (AHP) 10. Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary 11. Popa Mountain Park 12. Lawkananda Wildlife Sanctuary 13. Shwesattaw Wildlife Sanctuary 14. Wethtikan Bird Sanctuary 15. Moeyungyi Wetland Wildlife Sanctuary 16. Hlawga Park 17. Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary (AHP) 18. Thamihla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary 19. Lampi Marine National Park (AHP) 20. Myinghaywan Elephant Camp 21. Phokyar Elephant Camp 1 Table 1: Summary overview highlighting factors likely to influence tourism development Boxes highlighted in green indicate features lending themselves to tourism-related investment and development Boxes highlighted in orange indicate significant issues and difficulties to overcome to facilitate tourism growth 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 in in y ? hub ment Protected Area e diversity / diversity points (hours) Habitat tourism Established Established Communit existing Visitor -

Status and Distribution of Smaller Cats in Myanmar

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264057613 Status and distribution of smaller cats in Myanmar Article · July 2014 CITATIONS READS 10 724 7 authors, including: Saw Htoo Tha Po Kyaw Thinn Latt Wildlife Conservation Society.(Myanmar Program) Wildlife Conservation Society 8 PUBLICATIONS 98 CITATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS 75 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Antony J. Lynam Wildlife Conservation Society 94 PUBLICATIONS 1,995 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Myanmar Elephant Conservation Action Plan View project World Wildlife Fund View project All content following this page was uploaded by Antony J. Lynam on 21 July 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 8 | SPRING 2014 Non-CATPanthera cats in newsSouth-east Asia 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. -

Dos and Don'ts for Tourists

Dos Second Edition and Don’ts for Tourists How to be a responsible traveler in Myanmar Dos and Don’ts for Tourists in Myanmar 2nd Edition 2017 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the kind support of many individuals and organizations. We would like to extend our sincere thank you to all of them. We are indebted to Dr. Andrea Valentin and colleagues from Tourism Transparency for their guidance and for liaising with a wide range of stakeholders. We express our appreciation towards the UN International Trade Center for assisting us in setting up the revised Dos and Don’ts, and we express our gratitude to the Hanns Seidel Foundation, who first initiated this project with us in 2012 and continue their support until today. Our thanks and appreciation go to the Myanmar Responsible Tourism Institute for their thoughtful cooperation in this project, and the United Nations Children’s Fund for their considerate advice and support for child-safe tourism. Many thanks go to the Myanmar Information Management Unit for setting up the tourism map, and a special thank you goes to art director Karen Vinalay, who assembled the images and typography to create the Dos and Don’ts design. To the various stakeholders who provided their invaluable feedback, including the Myanmar Tourism Federation, the Myanmar Tourist Guide Association, Kayah rural communities and many others, we say thank you. Lastly, we express our deepest appreciation to the various talented Myanmar cartoonists, without whom this project would not have been possible: Ngwe Kyi, Aw Pi Kyal, Thit Htun, Harn Lay, Arkar, Moe Htet Moe, Thiha Skt, Thet Su, Chit Thu, Wai Yan and Shwe Lu. -

Biodiversity of the Ayeyarwady Basin

SOBA 4.5: BIODIVERSITY OF THE AYEYARWADY BASIN AYEYARWADY STATE OF THE BASIN ASSESSMENT (SOBA) Status: FINAL Last Updated: 13/01/2018 Prepared by: Christoph Zöckler with contributions from Maurice Kottelat (fish diversity) Disclaimer "The Ayeyarwady State of the Basin Assessment (SOBA) study is conducted within the political boundary of Myanmar, where more than 93% of the Basin is situated." i NATIONAL WATER RESOURCES COMMITTEE (NWRC) | AYEYARWADY STATE OF THE BASIN ASSESSMENT (SOBA) REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 4 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. 6 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 8 2 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND STATUS OF SPECIES........................................ 10 2.1 Mammals ......................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Birds ................................................................................................................. 22 2.3 Not Globally Threatened Waterbirds ............................................................ -

MM •R.N- Mis MM--Q3O

MM •R.N- mis _ MM--Q3O MM0200043 1. Introduction: The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is one the world's leading NGOs involved in conserving wildlife and ecosystems throughout the world through research, training and education. It was founded in April, 1895 with the initial aim of establishing a zoo at New York City, United States for educating the public about wildlife. At that time it was called "The New York Zoological Society." Through the concerted efforts of the Society, the "Bronx Zoo" was established where the Society has its offices now. The Society is actively involved not only in zoological work but also in world-wide conservation activities and accordingly changed the name of the Society to "The Wildlife Conservation Society" in 1993 to indicate its interest in wildlife conservation work all over the globe. Currently WCS is running over 300 wildlife conservation projects with the help of 60 scientists and 100 researchers throughout the world. The WCS Myanmar Program was initiated and founded by Dr. Alan Rabinowitz, Director of Science for Asia who signed the first Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Forest Department on 29 December 1993 for a period of four years from 1994 to 1997. Due to the successes achieved during this period, a second MoU was signed on 26 September for another five years from 1998 to 2002. At the present time WCS Myanmar Program is cooperating with the Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division of the Forest Department in carrying out wildlife conservation activities throughout the country in line with the framework set out in the MoU. -

The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar

The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar Thomas Geissmann Mark E. Grindley Ngwe Lwin Saw Soe Aung Thet Naing Aung Saw Blaw Htoo Frank Momberg People Resources and Conservation Foundation Fauna & Flora International Myanmar Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association Gibbon Conservation Alliance Karen Environmental and Social Action Network The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar by Thomas Geissmann, Mark E. Grindley, Ngwe Lwin, Saw Soe Aung, Thet Naing Aung, Saw Blaw Htoo, and Frank Momberg 2013 ii The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar Authors: Thomas Geissmann, Gibbon Conservation Alliance, and Anthropological Institute, University Zürich-Irchel, Winterthurerstr. 190, CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland Mark E Grindley, Chief Technical Officer, Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand Programs, People Resources and Conservation Foundation, Chiang Mai, Thailand Ngwe Lwin, Field Project Coordinator, Myanmar Primate Conservation Program, Yangon, Myanmar Saw Soe Aung, Senior Biologist, Myanmar Primate Conservation Program, Yangon, Myanmar Thet Naing Aung, Junior Biologist, Myanmar Primate Conservation Program, Yangon, Myanmar Saw Blaw Htoo, Community Conservation Manager, Karen Environmental and Social Action Network, Chiang Mai, Thailand Frank Momberg, Asia Director for Program Development, Fauna and Flora International, Jakarta, Indonesia Published by: Gibbon Conservation Alliance Anthropological Institute University Zürich-Irchel Winterthurerstrasse 190 CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland Email: [email protected] Web: www.gibbonconservation.org Copyright: © 2013 Fauna & Flora International, People Resources and Conservation Foundation, Myanmar Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association, and Gibbon Conservation Alliance. The copyright of the photographs used in this publication lies with the individual photographers. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial uses is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder(s) provided the source is fully acknowledged. -

Annual Report.Indd

Biodiversity And Nature Conservation Association (BANCA) Annual Report 2019 Contents Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Foreword …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association ………...………………………………………… 3 Major Achievements in 2019 ………………………...…………………………………………………. 9 Saving Species ……………………………………………..…………………………………………….. 11 Saving Sites and Habitat ……………………………...…………………………………… 22 Education, Awareness, Advocacy, Community Development and Empowerment Activities ....……… 29 Organizational Capacity Enhancement ……………………………...…………………………… 36 Membership Status ……………………………………………………...……………………………. 42 Financial status ………………………………………………………………………....… 43 Annexes …………………………………………………...……………………………………….. 44 Acronyms and Abbreviations BANCA Biodiversity And Nature MVWG Myanmar Vulture Workin Conservation Association Group BLI BirdLife International Asia NEA Norway Environmental Program Agency BOG Board of Governance NWCD Nature Wildlife CBO Community Based Conservation Division Organization OBC Oriental Bird Club CEPF Critically Ecosystem Partnership Fund RBANCA Rakhine Biodiversity and CR Critically Endangered Nature Conservation DU Dagon University Association DOF Department of Fishery RCJ Ramsar Center Japan EAAFP East Asian Australasian Flyway RT Rainforest Trust Partnership RSPB Royal Society for Protection ECD Environmental Conservation of Birds Department SAVE Saving Asian Vulture EESC Environmental Education and Extinction Sustainable Centre SDC Swiss Agency for EN Endangered Development and FD Forest -

Biodiversity in Myanmar, Including Protected Areas and Key Biodiversity Areas

Supplement to MCRB’s Briefing Paper on Biodiversity, Human Rights and Business Biodiversity in Myanmar, including Protected Areas and Key Biodiversity Areas November 2018 + 95 1 512613 | [email protected] | www.mcrb.org.mm +95 1 512613 [email protected] www.mcrb.org.mm This Supplement to MCRB’s Briefing Paper on Biodiversity, Human Rights and Business in Map 1: Ecoregions of Myanmar Myanmar gives further information about the biodiversity of Myanmar, its Protected Area (PA) Network and other Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA), which are critically important to protecting biodiversity and the ecosystem services they provide. It is structured as follows: A. Ecoregions B. Protected Areas of Myanmar and other Areas of Global Significance, including an overview of coverage representativeness, financing, governance, enforcement and social implications of protected area expansion C. Important Designations for Biodiversity Not Yet Protected (tentative World Heritage Sites and Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) in Myanmar) D. Main Ecosystems/Habitats of Myanmar, covering forests, limestone karst, freshwater ecosystems, wetlands, marine habitats and species Almost all of Myanmar lies within the Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot, one of 35 global hotspots that support high levels of biodiversity and endemism.1 The Indo-Burma hotspot ranks in the top 10 hotspots globally for irreplaceability and in the top five for threats. Myanmar supports an extraordinary array of ecosystems, with mountains, permanent snow and glaciers, -

Ijrtbt a Way to Achieve Success for Myanmar Ecotourism

IJRTBT A WAY TO ACHIEVE SUCCESS FOR MYANMAR ECOTOURISM Myo Aung Lincoln University College, Malaysia *Corresponding Author's Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Myanmar is one of the poorest countries in the World although it has good natural resources, geopolitical location. It is the northwestern-most country of mainland Southeast Asia, bordering China, India, Bangladesh, Thailand and Laos. Myanmar Economy faces serious challenges to gain probable benefits and success. Therefore, this research focuses on the assessment on Myanmar ecotourism strategy, potential sites and current challenges to develop ecotourism in Myanmar. There are geopolitics opportunities, high potential sites to develop sustainable ecotourism than other neighboring countries of South East Asia. This research recommended to apply good practices of international standard ecotourism sites, to build world peace through ecotourism, and to function ecotourism policy to poor community participations, etc. Keywords: Myanmar Ecotourism, Sustainable Ecotourism, Geopolitics, Peace Building, Community Participation INTRODUCTION ministry has permitted about 1,628 hotels and guest houses with some 65,470 rooms to operate as of March Myanmar is a land full of richness in nature and the 2018 (Global Times, 2018). Moreover, Myanmar's diversity of species. The ecosystems in this country Government implements obligatory policies, strategies constitute one of the biological reservoirs in Asia. The and regulations to foster tourism sector investment land area of Myanmar is 261,228 square miles, with a through private sectors of the country and Foreign Direct variety of natural resources, plants and animals. The Investment since 2015. Yangon city has the most Ministry of Forestry is responsible for maintaining the number of hotels in Myanmar, thus it has 395 hotels with forests of Myanmar. -

MYANMAR Ecotourism Policy & Management Strategy for Protected Areas Annex I Designated Ecotourism Sites: a STATUS REPORT

MYANMAR Ecotourism Policy & Management Strategy for Protected Areas Annex I Designated Ecotourism Sites: A STATUS REPORT 2015 - 2025 1 MYANMAR Ecotourism Policy & Management Strategy 2015 - 2025 This document has been produced by the Myanmar Ministry of Hotels and Tourism with technical support from the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) under the Support to Rural Livelihoods and Climate Change Adaptation Programme (Himalica) with funding from the European Union. The Ministry of Hotels and Tourism encourages printing or copying information in this document for personal and non commercial use with proper acknowledgment of Ministry of Hotels and Tourism, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of the Ministry of Hotels and Tourism, Myanmar. There are two supporting documents developed in parallel to this Ecotourism Policy and Management Strategy: Myanmar’s Designated Ecotourism Sites: A Status Report Guidelines for Developing Ecolodges in Myanmar (separate document) Cover Photo credits: Tun Aung ©2015 Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry, and Ministry of Hotels and Tourism, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar 2 Foreword Following significant economic, social and political reform, Myanmar is enjoying a sustained and rapid growth of its tourism industry. Visitors are keen to experience Myanmar’s world-renowned cities and unspoiled cultural heritage. Accompanying this growth is a demand, especially from discerning international travelers, to explore Myanmar’s natural heritage in ways that align with principles of responsibility and green growth. Myanmar is blessed with an extraordinary array of ecosystems that are rich in biodiversity, and frequently home to diverse ethnic peoples steeped with striking traditions and lifestyles. -

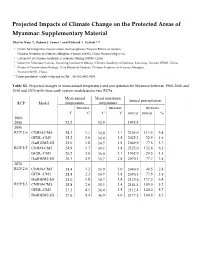

Projected Impacts of Climate Change on the Protected Areas of Myanmar: Supplementary Material

Projected Impacts of Climate Change on the Protected Areas of Myanmar: Supplementary Material Thazin Nwe 1,2, Robert J. Zomer 3 and Richard T. Corlett 1,4,* 1 Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Yunnan 666303, China; [email protected] 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Center for Mountain Futures, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China 4 Center of Conservation Biology, Core Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Yunnan 666303, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-182-8805-9408 Table S1. Projected changes in mean annual temperature and precipitation for Myanmar between 1960-2000 and 2050 and 2070 with three earth system models under two RCPs. Mean annual Mean maximum Annual precipitation RCP Model temperature temperature increase increase increase ˚C ˚C ˚C ˚C mm/yr mm/yr % 1960- 2000 23.2 32.9 1992.4 2050 RCP 2.6 CNRM-CM5 24.3 1.1 34.0 1.1 2105.9 113.5 5.4 GFDL-CM3 25.2 2.0 34.4 1.5 2025.3 32.9 1.6 HadGEM2-ES 25.0 1.8 34.7 1.8 2069.9 77.5 3.7 RCP 8.5 CNRM-CM5 24.9 1.7 34.3 1.4 2125.0 132.6 6.2 GFDL-CM3 26.2 3.0 36.0 3.1 1962.9 -29.5 -1.5 HadGEM2-ES 26.1 2.9 35.7 2.8 2070.1 77.7 3.8 2070 RCP 2.6 CNRM-CM5 24.4 1.2 33.9 1.0 2040.9 48.5 2.4 GFDL-CM3 25.5 2.3 34.7 1.8 2070.3 77.9 3.8 HadGEM2-ES 25.0 1.8 34.7 1.8 2129.6 137.2 6.4 RCP 8.5 CNRM-CM5 25.8 2.6 35.3 2.4 2101.4 109.0 5.2 GFDL-CM3 27.3 4.1 36.4 3.5 2112.4 120.0 5.7 HadGEM2-ES 27.6 4.4 36.9 4.0 2177.2 184.8 8.5 CNRM-CM5 (RCP2.6) CNRM-CM5 (RCP 8.5) GFDL-CM3 (RCP2.6) GFDL-CM3 (RCP8.5) HadGEM2-ES (RCP2.6) HadGEM2-ES (RCP8.5) Figure S1.