Native Child Welfare‟ in Durban, 1930-1939 Marijke Du Toit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Durban 2

Durban is a vibrant and dynamic city of contrasts with a potent and exciting mix of cultures. A natural paradise known for its beautiful coastline and subtropical climate, situated on the eastern seaboard of Africa. The city focuses on providing with a unique set of experiences that go beyond the beach and into the the realm of Durban's diverse culture, urban lifestyle and scenic diversity There is so much to do and see, you will have to come back again and again to experience all that it has to offer... With a miles of golden beaches, people from all over the world have been visiting Durban for years because of its reputation for all-year-round sunshine. If the Beach Boys were South African, their hit “Califonia Girls” would be about Durban! Surfing is a way of life in Durban The Natal Midlands. Set amidst forested hills and the rolling countryside, dominated by green pastures and pine forests, dotted with a myriad of waterfalls, lakes, dams and zulu villages, this region offers an eclectic and fascinating mix of arts and crafts, world class restaurants and homely comforts with a wide range of adventurous natural and historic pursuits. Kaarkloof Falls in Howick Although a bustling metropolils, Durban has an amazing abundance of wildlife right on its doorstep. Choose from deep lush valleys, mangrove swamps, and crocodile and reptile reserves to name a few. Tala Game Reserve is located in the Midlands of KwaZulu Natal. It is a prime destination for visitors to Durban to see African wildlife without having to travel too far. -

Struggle for Liberation in South Africa and International Solidarity A

STRUGGLE FOR LIBERATION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY A Selection of Papers Published by the United Nations Centre against Apartheid Edited by E. S. Reddy Senior Fellow, United Nations Institute for Training and Research STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED NEW DELHI 1992 INTRODUCTION One of the essential contributions of the United Nations in the international campaign against apartheid in South Africa has been the preparation and dissemination of objective information on the inhumanity of apartheid, the long struggle of the oppressed people for their legitimate rights and the development of the international campaign against apartheid. For this purpose, the United Nations established a Unit on Apartheid in 1967, renamed Centre against Apartheid in 1976. I have had the privilege of directing the Unit and the Centre until my retirement from the United Nations Secretariat at the beginning of 1985. The Unit on Apartheid and the Centre against Apartheid obtained papers from leaders of the liberation movement and scholars, as well as eminent public figures associated with the international anti-apartheid movements. A selection of these papers are reproduced in this volume, especially those dealing with episodes in the struggle for liberation; the role of women, students, churches and the anti-apartheid movements in the resistance to racism; and the wider significance of the struggle in South Africa. I hope that these papers will be of value to scholars interested in the history of the liberation movement in South Africa and the evolution of United Nations as a force against racism. The papers were prepared at various times, mostly by leaders and active participants in the struggle, and should be seen in their context. -

Rev Dr Scott Couper

“A Sampling: Artefact, Document and Image” Rev Dr Scott Couper 18 March 2015 Forum for Schools and Archives AGM, 2015 The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Mission established Inanda Seminary in March 1869 as a secondary school for black girls. For a school to be established for black girls at this time was unheard of. It’s founding was radical, as radical as its first principal, Mary Kelly Edwards, the first single female to be sent by the American Board to southern Africa. Many of South Africa’s most prominent female leadership are products of the Seminary. Inanda Seminary produces pioneers: Nokutela Dube, co-founder of Ohlange Institute with her husband the Reverend John Dube, first President of the African National Congress (ANC), attended the Seminary in the early 1880s. Linguists and missionaries Lucy and Dalitha Seme, sisters of the ANC’s founder Pixley Isaka kaSeme, also attended the Seminary in the 1860s and 1870s. Anna Ntuli became the first qualified African nurse in the Transvaal in 1910 and married the first African barrister in southern Africa, Alfred Mangena. Nokukhanya Luthuli attended from 1917-1919 and taught in 1922 at the Seminary. Nokukhanya accompanied her husband, Albert Luthuli who was the ANC President-General and a member of the Seminary’s Advisory Board, to Norway to receive the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize in 1961. Edith Yengwa also schooled and taught at the Seminary; she attended from 1940, matriculated in 1946, began teaching in 1948 and became the school’s first black head teacher in 1966. The same year she left the Seminary for exile, joining her husband, Masabalala Yengwa, the Secretary of the Natal ANC. -

Location in Africa the Durban Metropolitan Area

i Location in Africa The Durban Metropolitan area Mayor’s message Durban Tourism am delighted to welcome you to Durban, a vibrant city where the Tel: +27 31 322 4164 • Fax: +27 31 304 6196 blend of local cultures – African, Asian and European – is reected in Email: [email protected] www.durbanexperience.co.za I a montage of architectural styles, and a melting pot of traditions and colourful cuisine. Durban is conveniently situated and highly accessible Compiled on behalf of Durban Tourism by: to the world. Artworks Communications, Durban. Durban and South Africa are fast on their way to becoming leading Photography: John Ivins, Anton Kieck, Peter Bendheim, Roy Reed, global destinations in competition with the older, more established markets. Durban is a lifestyle Samora Chapman, Chris Chapman, Strategic Projects Unit, Phezulu Safari Park. destination that meets the requirements of modern consumers, be they international or local tourists, business travellers, conference attendees or holidaymakers. Durban is not only famous for its great While considerable effort has been made to ensure that the information in this weather and warm beaches, it is also a destination of choice for outdoor and adventure lovers, eco- publication was correct at the time of going to print, Durban Tourism will not accept any liability arising from the reliance by any person on the information tourists, nature lovers, and people who want a glimpse into the unique cultural mix of the city. contained herein. You are advised to verify all information with the service I welcome you and hope that you will have a wonderful stay in our city. -

Preferred Provider Pharmacies

PREFERRED PROVIDER PHARMACIES Practice no Practice name Address Town Province 6005411 Algoa Park Pharmacy Algoa Park Shopping Centre St Leonards Road Algoapark Eastern Cape 6076920 Dorans Pharmacy 48 Somerset Street Aliwal North Eastern Cape 346292 Medi-Rite Pharmacy - Amalinda Amalinda Shopping Centre Main Road Amalinda Eastern Cape Shop 1 Major Square Shopping 6003680 Beaconhurst Pharmacy Cnr Avalon & Major Square Road Beacon Bay Eastern Cape Complex 213462 Clicks Pharmacy - Beacon Bay Shop 26 Beacon Bay Retail Park Bonza Bay Road Beacon Bay Eastern Cape 6071864 The Bedford Pharmacy 34 Donkin Street Bedford Eastern Cape 6003699 Berea Pharmacy 31 Pearce Street Berea Eastern Cape 192546 Clicks Pharmacy - Cleary Park Shop 4 Cleary Park Centre Standford Road Bethelsdorp Eastern Cape Cnr Stanford & Norman Middleton 245445 Medi-Rite Pharmacy - Bethelsdorp Cleary Park Shopping Centre Bethelsdorp Eastern Cape Road 95567 Klinicare Bluewater Bay Pharmacy Shop 6-7 N2 City Shopping Centre Hillcrest Drive Bluewater Bay Eastern Cape 6017029 Burgersdorp Pharmacy 27 Taylor Street Burgersdorp Eastern Cape 478806 Medi-Rite Pharmacy - Butterworth Fingoland Mall Umtata Street Butterworth Eastern Cape 6067379 Cambridge Pharmacy 18 Garcia Street Cambridge Eastern Cape 6082084 Klinicare Oval Pharmacy 17 Westbourne Road Central Eastern Cape 6078451 Marriott and Powell Pharmacy Prudential Building 40 Govan Mbeki Avenue Central Eastern Cape 379344 Provincial Westbourne Pharmacy 84c Westbourne Road Central Eastern Cape 6005977 Rink Street Pharmacy 4 Rink Street -

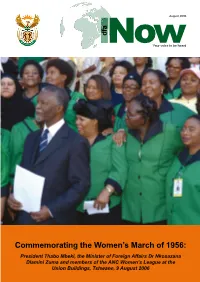

Commemorating the Women's March of 1956

August 2006 dfa NowYour voice to be heard Commemorating the Women’s March of 1956: President Thabo Mbeki, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma and members of the ANC Women’s League at the Union Buildings, Tshwane, 9 August 2006 Editorial Note Welcome to another informative issue. August is women’s month and in joining the million echoes salut- The DFA Now is an internal newsletter of Department ing all the great women of the world, the DFA Now has included of Foreign Affairs published by the Directorate: Content the following extract from a poem written & composed by: Mvuyo Development. Mhangwane entitled ‘To our liberation’s heroines’ in recognition of the unselfish contribution that women has and continue to make in Editor-in-Chief: Ronnie Mamoepa working for a better world - Amandla “the mighty Mbokodo!” Editor: ... Transport your memory to August 9th, 1956 Paseka Mokhethea Visualise the determined face of Lilian Masediba Ngoyi Acknowledge the gallant gait of Helen Joseph Editorial Committee: Applaud the resolve in Radima Moosa’s voice Genge, MP: (Acting) Chief Dir: Policy, Research & Analysis; What a formidable convoy of untouchable rocks? Khoza, G: Dir: Operations Centre; That sent shivers down apartheid’s evil heart Moloto, J: Dir: Office of the Deputy Minister; Rendering Strijdom and his brutal accomplices panic-stricken Dikweni, NL: Dir: Economic Policy and Programming; Mashabane, D: Dir Humanitarian Affairs; Laying a solid foundation for April 27th, 1994 Nompozolo, Mathu: Chief Dir Human Resources; You set a trend for nations to emulate Shongwe, LV: Dir: Office of the DG; Banished fallacies and myths about female powerlessness to the Malcomson, D: Dir NEPAD, ARF, Programme & grave Information Management; Mabhongo, X: Dir : United Nations; Mountains of accolades are due to you .. -

Trade Guide Welcome to Durban Accessability and Transport Infrastructure

Contents Welcome to Durban ...................................................................... 2 Useful information ........................................................................ 2 Accessability and transport infrastructure ................................. 3 Getting around Durban ................................................................ 4 Accommodation ............................................................................ 6 Meetings, incentives, conferences and events in Durban ........ 8 Wining and dining in Durban ................................................... 10 Message Experiences in Durban ............................................................... 12 Experiences to the north, south and west ................................ 18 from the Mayor Mixing with the locals in a vibrant township .......................... 21 Hot nightlife and great entertainment ...................................... 23 he City of Durban has made a name for itself as a tourism dotted with holiday towns; both are less than an hour’s drive Shop till you drop ........................................................................ 26 and holiday destination of choice for more than half a from the City centre. To the north of the City lies the bustling City tours ...................................................................................... 28 century now, and that can be attributed to, among many coastal town of Umhlanga, packed with hotels, restaurants T Durban’s rich culture, heritage and architecture .................... -

AWG Champion, Zulu Nationalism and ‘Separate Development’ in South Africa, 1965 - 1975

AWG Champion, Zulu Nationalism and ‘Separate Development’ in South Africa, 1965 - 1975. by WONGA FUNDILE TABATA submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF GC CUTHBERTSON JOINT SUPERVISOR: PROF J LAMBERT NOVEMBER 2006 Abstract This is a historical study of AWG Champion, the former leader of the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU) and provincial President of the African National Congress, in the politics of Zululand and Natal from 1965 to 1975. The study examines the introduction of the Zulu homeland and how different political forces in that region of South Africa responded to the idea of a Zulu homeland during the period under review. It also deals with Champion’s political alienation from the ANC. This dissertation is also a study of the development of Zulu ethnic nationalism within the structures of apartheid or separate development, the homelands. Issues running throughout the study are the questions of how and why Champion tried and failed to manipulate ‘separate development’ in order to build a Zulu ethnic political base. Key words: A.W.G. Champion, Zulu Nationalism, ‘Separate Development’, apartheid, African National Congress, trade unions, Black Consciousness. iii Declaration I declare that AWG Champion, Zulu Nationalism and ‘Separate Development’ in South Africa, 1965-1975 is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of completed references. ________________________________ __________________ Mr W F Tabata Date iv Dedication To my parents, the late Kolisile Boyce Tabata and Nellie Nikiwe Tabata And all my brothers and only sister, Kayakazi “Mela” My wife, Nomathamsanqa and children With sincere thanks For their love and encouragement During the writing of this dissertation Not forgetting my Grandmother, The late Beatrice “Gelikha” Tabata, “iBhelekazi” Whose love for education served as an inspiration and her spirit guided me through the writing process of this dissertation. -

Wall of Remembrance

Wall of Remembrance Josie Palmer This wall honours a small selection of women 1903 - 1979 who played a key role in South African history; it does not include or mention all the role players. Political activist and leading gure in the SACP and FEDSAW For more proles visit www.sahistory.org.za Olive Schreiner Ida Mntwana 1855 –1920 1903-1960 Early South African feminist, anti-war campaigner, au- Political activist, rst president of the ANCWL and rst Na- thor and intellectual tional President of FEDSAW (1954-1956) Charlotte Maxeke 1874 - 1939 Helen Joseph 1905 - 1992 Political activist, religious leader, South Africa’s rst black women graduate and one of the rst black South Africans Teacher, political activist, trade unionist and founding to ght for women’s rights member of the South African Congress of Democrats and FEDSAW Cecilia Makiwane 1880 - 1919 Annie Silinga 1910-1984 The rst registered professional black nurse in South Africa, early activist in the struggle for women’s rights Political activist, member of the National Executive Com- and protestor in the rst anti-women’s pass campaign in mittee of FEDSAW and president of the Cape Town branch 1912. of the ANCWL Bertha Mkhize 1889 - 1981 Florence Matomela 1910-1969 Political activist, trade unionist, President of ANC Wom- en’s League (1956) Teacher and ANCWL organiser and vice-president of FED- SAW in the mid-1950s Cissie Gool 1897 - 1963 Lilian Masediba Ngoyi 1911 -1980 Political activist, civil rights leader, founder of the Nation- al Liberation League and the Non-European United -

Kwazulu-Natal Incentive Guide and Catalogue

KWAZULU-NATAL Incentive Guide and Catalogue The Zulu Kingdom World’s best kept secret A place of discovery, and a business events destination never to be forgotten P O Box 2516, Durban, 4000, South Africa tel: +27 31 366 7577/80 email: [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 2 Letters of support ONCE IN A LIFetime – DURBAN TO DRAKENSBERG – the ultimate KwaZulu-Natal incentive programme KwaZulu-Natal South Coast – a gem in the making 3 can be found within this catalogue 7 KwaZulu-Natal – a hub of activities FOREWORD waZulu-Natal is rich in its diversity We are also proud of our “beach of people and experiences. The culture” that is influenced by a range Kprovince has “something” which of world-class beaches, internationally- offers visitors leisure, cultural and action recognised surf spots and shark diving adventures ranging from the bush, the reefs. These can be experienced just to berg, the battlefields, the beaches to the the north and south of Durban at sites “Big Five” wildlife. such as “Aliwal Shoal”. Styled as the Zulu Kingdom, KwaZulu- This scuba diving site is regarded Natal has incentive activities which are as one of the top 10 shark diving varied and numerous, in the setting experiences in the world. of magnificent vistas and modern Close by is the famous Oriba Gorge, facilities, and conducted by operators which includes one of the third most of the highest standard who are able to significant “bungi swings” on the globe. create itineraries to suit a wide variety of James Seymour These Durban experiences can also requirements. -

Gender and Class Dynamics During the Quest to Restore Inanda Seminary's

Gender and class dynamics... Inanda Seminary’s financial integrity, 1999-2001, New Contree, 77, December 2016, pp. 100-122 “Let’s do things on our own …”: Gender and class dynamics during the quest to restore Inanda Seminary’s financial integrity, 1999-2001 Scott Everett Couper University of KwaZulu-Natal [email protected] It would really be a sin to let this great institution die out while we are all looking Mangosuthu Buthelezi, 1999 Abstract During the 1990s, decades of disinvestment caused by Bantu Education prohibited Inanda Seminary from competing equally with other previously advantaged Whites-only private and former public ‘Model C’ schools within South Africa’s new democratic dispensation. In December 1997, after decades of institutional corrosion, the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa decided to close the Seminary. Yet, the Seminary opened in January 1998 under new management composed entirely of middle-class alumnae determined to breathe new life into the school still teetering precariously. This article chronicles three years, 1999 to 2001, thereby documenting the school’s ultimate defeat over and recovery from Bantu Education. Though Inanda Seminary’s middle-class alumnae saved it from closure, its more elite graduates did not initially feature prominently in the school’s financial stabilisation. Rather, men, both serving the church and government (most notably, Nelson Mandela), intervened and provided the crucial financial and infrastructural impetus to salvage the school from the wreck of ecclesiastic decay and establish it as a Section 21 private company. The article explores if and why gender and class dynamics likely played a role in the events leading to the school’s resuscitation. -

The Family Politics of the Federation of South African Women: a History of Public Motherhood in Women’S Antiracist Activism

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University History Faculty Publications History Department 2017 The aF mily Politics of the Federation of South African Women: A History of Public Motherhood in Women’s Antiracist Activism Meghan Healy-Clancy Bridgewater State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/history_fac Part of the African History Commons, African Languages and Societies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Virtual Commons Citation Healy-Clancy, Meghan (2017). The aF mily Politics of the Federation of South African Women: A History of Public Motherhood in Women’s Antiracist Activism. In History Faculty Publications. Paper 70. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/history_fac/70 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Meghan Healy-Clancy The Family Politics of the Federation of South African Women: A History of Public Motherhood in Women’s Antiracist Activism Winner of the 2017 Catharine Stimpson Prize for Outstanding Feminist Scholarship n the austral summer of 1972, Lilian Ngoyi sat down in her matchbox I house in Soweto, Johannesburg, and wrote her life story. “Born in Pre- toria Blood St 1911[, I] was the only girl in a family of five boys,” this story began. “I wish I could be reborn to put my shoulders under the wheel of freedom. Freedom of all my children. An Africa where there would be food for all. Universal & compulsory education,” this story ended.1 As she was writing, Ngoyi had been confined to her home for a decade: she had been banned from public engagement in South Africa for her activism against apartheid, the regime of racial separation and inequality introduced in 1948.2 She wrote at the request of a sponsor at Amnesty International, which was supporting her as a prisoner of conscience (Daymond 2015, 253–61).