Rick and Morty and Narrative Instability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Nomination Press Release Outstanding Character Voice-Over Performance F Is For Family • The Stinger • Netflix • Wild West Television in association with Gaumont Television Kevin Michael Richardson as Rosie Family Guy • Con Heiress • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin, Stewie Griffin, Brian Griffin, Glenn Quagmire, Tom Tucker, Seamus Family Guy • Throw It Away • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Alex Borstein as Lois Griffin, Tricia Takanawa The Simpsons • From Russia Without Love • FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe, Carl, Duffman, Kirk When You Wish Upon A Pickle: A Sesame Street Special • HBO • Sesame Street Workshop Eric Jacobson as Bert, Grover, Oscar Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The Planned Parenthood Show • Netflix • A Netflix Original Production Nick Kroll, Executive Producer Andrew Goldberg, Executive Producer Mark J. Levin, Executive Producer Jennifer Flackett, Executive Producer Joe Wengert, Supervising Producer Ben Kalina, Supervising Producer Chris Prynoski, Supervising Producer Shannon Prynoski, Supervising Producer Anthony Lioi, Supervising Producer Gil Ozeri, Producer Kelly Galuska, Producer Nate Funaro, Produced by Emily Altman, Written by Bryan Francis, Directed by Mike L. Mayfield, Co-Supervising Director Jerilyn Blair, Animation Timer Bill Buchanan, Animation Timer Sean Dempsey, Animation Timer Jamie Huang, Animation Timer Bob's Burgers • Just One Of The Boyz 4 Now For Now • FOXP •a g2e0 t1h Century -

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) Warsaw 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Justyna Fruzińska, Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Łukasz Muniowski, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Ewa Antoszek, Edyta Frelik, Elżbieta Klimek-Dominiak, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Tadeusz Pióro, Elżbieta Rokosz-Piejko, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Stefan Schubert, Joanna Ziarkowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Vegas Options” from the series “Las Vegas.” By permission. www.flickr/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733-9154 eISSN 2544-8781 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02-653 Warsaw paas.org.pl Nakład 110 egz. Wersją pierwotną Czasopisma jest wersja drukowana. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents ARTICLES Justyna Włodarczyk Beyond Bizarre: Nature, Culture and the Spectacular Failure of B.F. Skinner’s Pigeon-Guided Missiles .......................................................................... 5 Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s ................................................................ 19 Arkadiusz Misztal Dream Time, Modality, and Counterfactual Imagination in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon ............................................................................... 37 Ewelina Bańka Walking with the Invisible: The Politics of Border Crossing in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway: A True Story ............................................. -

MEDIA ALERT for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Stoopid Buddy Stoodios

MEDIA ALERT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Stoopid Buddy Stoodios—creative minds behind Robot Chicken TV Series—to visit The Walt Disney Family Museum in April! San Francisco, CA (March 29, 2013)—Celebrate the closing of exhibition Between Frames: The Magic Behind Stop Motion Animation with a lineup of events featuring the creators of Robot Chicken and the founders of Stoopid Buddy Stoodios! Join the team comprised of Seth Green (creator), Matthew Senreich (creator), John Harvatine IV (owner), Eric Towner (owner), and Alex Kamer (animation supervisor) for an after hours party, programs, and a workshop, exclusive to The Walt Disney Family Museum the last weekend of April. AFTER HOURS PARTY Animate Your Night: The Island of Misfit Toys Friday, April 26 | 7–10pm | Museum-wide Party with us after hours for a night full of misfit adventure! Join the creators of Robot Chicken and the founders of Stoopid Buddy Stoodios as they present behind the scenes footage and episode clips, followed by a Q&A. Enjoy eats from Adam’s Grub Truck and Me So Hungry, then have a hair-raising sip of our signature cocktail: The Evil Doctor. PANEL DISCUSSION The Making of Robot Chicken Saturday, April 27 | 2pm | The Theater Join the crew from Stoopid Buddy Stoodios, the masterminds behind the stop motion TV show Robot Chicken, for a behind-the-scenes look at the making of this modern cult favorite. WORKSHOP Learn from the Masters: Animation Mischief with Stoopid Buddy Stoodios Saturday, April 27 | 10am–1pm | Art Studio Explore the magic of stop motion animation with the Emmy and Annie Award-winning animators of Robot Chicken. -

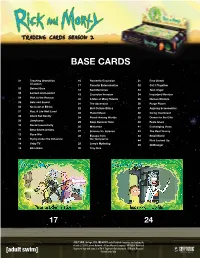

Rick and Morty Season 2 Checklist

TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 BASE CARDS 01 Teaching Grandkids 16 Romantic Excursion 31 Emo Streak A Lesson 17 Parasite Extermination 32 Get It Together 02 Behind Bars 18 Bad Memories 33 Teen Angst 03 Locked and Loaded 19 Cromulon Invasion 34 Important Member 04 Rick to the Rescue 20 A Man of Many Talents 35 Human Wisdom 05 Safe and Sound 21 The Ascension 36 Purge Planet 06 No Code of Ethics 22 Bird Culture Ethics 37 Aspiring Screenwriter 07 Roy: A Life Well Lived 23 Planet Music 38 Going Overboard 08 Silent But Deadly 24 Peace Among Worlds 39 Dinner for the Elite 09 Jerryboree 25 Keep Summer Safe 40 Feels Good 10 Racial Insensitivity 26 Miniverse 41 Exchanging Vows 11 Beta-Seven Arrives 27 Science Vs. Science 42 The Real Tammy 12 Race War 28 Escape from 43 Small World 13 Flying Under the Influence the Teenyverse 44 Rick Locked Up 14 Unity TV 29 Jerry’s Mytholog 45 Cliffhanger 15 Blim Blam 30 Tiny Rick 17 24 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. A Time Warner Company. All Rights Reserved. Cryptozoic logo and name is a TM of Cryptozoic Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 CHARACTERS chase cards (1:3 packs) C1 Unity C7 Mr. Poopybutthole C2 Birdperson C8 Fourth-Dimensional Being C3 Krombopulos Michael C9 Zeep Xanflorp C4 Fart C10 Arthricia C5 Ice-T C11 Glaxo Slimslom C6 Tammy Gueterman C12 Revolio Clockberg Jr. C1 C3 C9 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. -

Stop Motion in Popular Culture: a Case Studyin Series Production of ‘Rilakkuma and Kaoru’ ______Sakkra Paiboon*

สตอปโมชันในวัฒนธรรมสมัยนิยม: กรณีศึกษาการสร้างสรรค์ ซีรี่ส์‘Rilakkuma and Kaoru’ Stop Motion in Popular Culture: a Case Studyin Series Production of ‘Rilakkuma and Kaoru’ ___________________________________________________________________________ Sakkra Paiboon* บทคัดย่อ บทคว�มสตอปโมชันในวัฒนธรรมสมัยนิยมฉบับนี้ มีจุดมุ่งหม�ยเพื่อศึกษ�คว�มนิยมของสตอป โมชัน ในช่วงปล�ยศตวรรษที่ 20 จนถึงต้นศตวรรษที่ 21 โดยมุ่งเน้นไปยังอิทธิพล ก�รนับเป็นปัจเจกตัว ตนในประเภทย่อยของอนิเมชัน ผลกระทบของก�รปรับเปลี่ยนไปในก�รรับสื่อ ตลอดจนก�รดำ�รงอยู่ของ สตอปโมชันในสื่อร่วมสมัย บทคว�มนี้ จะวิเคร�ะห์แนวคิดริเริ่ม และวิธีก�รสร้�งสรรค์สตอปโมชันซี รีส์‘Rilakkuma and Kaoru’ ซึ่งเผยแพร่บนสื่อสตรีมมิ่งออนไลน์ยักษ์ใหญ่อย่�ง Netflix โดยจำ�แนกถึง ร�ยละเอียดของก�รสร้�งสรรค์ผลง�นด้วยเทคนิคอนิเมชันสมัยใหม่ ซึ่งมีส่วนช่วยให้สตอปโมชันยังคงอยู่ ได้บนสื่อวัฒนธรรมสมัยนิยมร่วมสมัย คำาสำาคัญ: สตอปโมชัน / ประเภทสื่อ / วัฒนธรรมสมัยนิยม / เทคนิคอนิเมชัน Abstract Stop motion in popular culture aims to study the popularity of stop motion over the late 20th century until early 21st century with focuses on its influence, its identity as a sub-genre of animation, the affects in the shift of media reception as well as how stop motion can find its place in contemporary media. The article analyses the inception and production of the stop motion series ‘Rilakkuma and Kaoru’ that is available on the giant streaming service Netflix. Detailing the production of this series that shows the utilisation of modern animation techniques that helps stop motion to remain relevant to the contemporary pop culture. -

West Campus SGA Debate Meet the Candidates Talk Nerdy to Me Presidential Candidate Discusses Important Issues Pg

NEWS OPINION FEATURES SPORTS MEGACON 1 March 30, 2011 VOLUME 15 • ISSUE 13 VALENCIAVOICE.COM West Campus SGA debate Meet the candidates Talk Nerdy to Me Presidential candidate discusses important issues Pg. 4 Shardeh Berry By James Austin Chief-of-staff and VCC student RDV Sportsplex to host West Campus Vice Presidential candidate [email protected] since Fall 2009, said that he wanted sports, and increasing school spirit • Current Parlimentarian of SGA to bring back intramural sports to by holding pep rallies, campus • Platform: The right to vote is one of our West Campus, would work to create competitions and fundraisers to Richer variety of courses for nations founding principles. It gives a mentorship program avalible for support campus clubs. those who can only us, the citizens, the opportunity to Though she is running access one campus make our society better by electing unopposed, the Vice Presidential leaders who we think best represent candidate Berry released her own our thoughts and beliefs. platform that she will be focusing Wendell Smith Jr It’s time again for Valencia’s on in the coming year, including Presidential candidate Student Government elections and encouraging more students to to help the student body make an actively participate in campus • Current Vice President of SGA Playlist Live educated decision the West Campus events. She also wants to focus on • Platform: SGA debates were held on the SSB making more courses available to Increase student participation patio this past Tuesday. all campus’s. Partner with local sportsplex to Pg. 7 host club sports. There were three candidates The power of the people is a scheduled to participate in the guiding light in the politics of this debates. -

Shock Entertainment Dealer Guide SEPTEMBER 2018

DEALER GUIDE SEPTEMBER 2018 SUPERSTORE AIR CRASH INVESTIGATION - SEASON 17 REVENGE OF THE CREATURE COVER TITLE: SUPERMANSION - SEASON 1 FROM THE PEOPLE THAT BROUGHT YOU ROBOT CHICKEN. DEALER GUIDE CONTENTS 03 SUPERMANSION - SEASON 1 04 SUPERMANSION - SEASON 2 1 05 SUPERSTORE - SEASON 1 06 SUPERSTORE - SEASON 2 07 AIR CRASH INVESTIGATION - SEASON 17 08 INVISIBLE MAN'S REVENGE 09 REVENGE OF THE CREATURE 10 DEATH AT A FUNERAL 11 LIFE 12 THE INTERNATIONAL 13 FUN WITH DICK & JANE 14 BEVERLY HILLS NINJA 15 HOW HIGH 16 RUDY WWW.SHOCK.COM.AU SUPERMANSION SEASON 1 RELEASE DATE 01.09.18 SUPERMANSION - SEASON 1 The League of Freedom is a superhero group that is led by the aging superhero Titanium Rex. From their base called SuperMansion in the fictional Storm City, Titanium Rex and his fellow superheroes Black Saturn, American Ranger, Jewbot/Robobot, Cooch, and Brad struggle to keep the team relevant even if it involves fighting an assortment of supervillains like Dr. Devizo as well as Titanium Rex's daughter Lex Lightning. SALES & MARKETING KEY SELLING POINTS • Aging superhero, Titanium Rex, and his has-been team known as The League of Freedom struggle to stay relevant in a changing world. • Supermansion is created by Zeb Wells and Matthew Senreich, the same creaters of stop motion comedy Robot Chicken. • The series stars Oscar nominated actor Bryan Cranston (Breaking Bad, Isle of Dog), SPECS Emmy winner Keegan-Michael Key (Key & Peele, Friends from College) as well LABEL: SHOCK as Chris Pine (Wonder Woman & Star Trek: Beyond). RATING: • The series has been nominated for two Primetime Emmys. -

Shawn Patterson

SHAWN PATTERSON SELECTED CREDITS MAKING APES: THE ARTISTS WHO CHANGED FILM (2019) THE LEGO MOVIE (2014) SUPERMANSION (2015-2019) THE ADVENTURES OF PUSS IN BOOTS (2015-2018) ROBOT CHICKEN (2010-2014) BIOGRAPHY Shawn Patterson is an Academy Award, Emmy and Grammy nominated Composer, Songwriter and Music Producer. Originally hailing from Athol, Massachusetts, Patterson's lifelong passion for music started with his late father, Ronald Patterson, a multi-instrumentalist musician. As a child, Shawn was exposed to television shows whose music scores (and sometimes songs) became engrained in his head: ‘Star Trek’, ‘The Six Million Dollar Man’, ‘Lost In Space’, and ‘Starsky & Hutch’. But it was his introduction to John Williams' legendary scores of ‘Star Wars’ and ‘Superman’ that initiated Patterson's profound life long journey to become a score composer and a part of cinematic storytelling through music. Shawn attended Berklee College of Music and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; where he was selected to study privately and perform with legendary jazz musicians Dr. Billy Taylor and Max Roach. As a jazz, blues, rock guitarist and bandleader, Shawn played shows and lead various bands (including trio, duo and solo settings) while writing compositions in his free time. In 1987, Patterson attended and graduated from the Grove School of Music in Studio City, California. While attending Grove, Shawn studied orchestration and arranging privately with Roger Steinman. After relocating to Los Angeles in 1990, Patterson studied composition and orchestration privately with legendary Los Angeles Composer and Orchestrator, Jack Smalley. Patterson soon found success writing music for film trailers around town. Over the years, Shawn has composed score and written songs in an enormous wide range of styles for a number of award winning episodic television shows. -

Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming Less Than One Hour)

Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Outstanding Animated Program (For Corey Campodonico, Producer Programming Less Than One Hour) Alex Bulkley, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer Creature Comforts America • Don’t Choke To Death, Tom Root, Head Writer Please • CBS • Aardman Animations production in association with The Gotham Group Jordan Allen-Dutton, Writer Mike Fasolo, Writer Kit Boss, Executive Producer Charles Horn, Writer Miles Bullough, Executive Producer Breckin Meyer, Writer Ellen Goldsmith-Vein, Executive Producer Hugh Sterbakov, Writer Peter Lord, Executive Producer Erik Weiner, Writer Nick Park, Executive Producer Mark Caballero, Animation Director David Sproxton, Executive Producer Peter McHugh, Co-Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eternal Moonshine of the Simpson Mind • Jacqueline White, Supervising Producer FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Kenny Micka, Producer James L. Brooks, Executive Producer Gareth Owen, Producer Matt Groening, Executive Producer Merlin Crossingham, Director Al Jean, Executive Producer Dave Osmand, Director Ian Maxtone-Graham, Executive Producer Richard Goleszowski, Supervising Director Matt Selman, Executive Producer Tim Long, Executive Producer King Of The Hill • Death Picks Cotton • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television in association with 3 Arts John Frink, Co-Executive Producer Entertainment, Deedle-Dee Productions & Judgemental Kevin Curran, Co-Executive Producer Films Michael Price, Co-Executive Producer Bill Odenkirk, Co-Executive Producer Mike Judge, Executive Producer Marc Wilmore, Co-Executive Producer Greg Daniels, Executive Producer Joel H. Cohen, Co-Executive Producer John Altschuler, Executive Producer/Writer Ron Hauge, Co-Executive Producer Dave Krinsky, Executive Producer Rob Lazebnik, Co-Executive Producer Jim Dauterive, Executive Producer Laurie Biernacki, Animation Producer Garland Testa, Executive Producer Rick Polizzi, Animation Producer Tony Gama-Lobo, Supervising Producer J. -

Seth Green Surprised Robot Chicken Lasted to 100 Episodes

June 9 - 15, 2012 | WWW.PGCITIZEN.CA A&E 31 Seth Green surprised Robot Chicken lasted to 100 episodes Nick PATCH The Canadian Press a stunning array of Hollywood A-listers into its cracked world, including Sarah Michelle TORONTO — When Seth Green launched Gellar, Mila Kunis, Snoop Dogg, Megan Fox, Robot Chicken back in 2005, he thought the Scarlett Johansson, Conan O’Brien, Ryan same thing most viewers likely did – that Seacrest and Charlize Theron. the scattershot animated gag machine was a But perhaps the biggest boon to the show’s fun diversion destined for a TV lifespan not fortune was timing. much longer than one of its pithy sketches. Less than a week before Robot Chicken So with the 100th episode of the Emmy- hit the airwaves, YouTube launched and winning troublemaking-with-toys comedy suddenly seized upon and furthered the set to air on Teletoon this Sunday night, the Internet’s collectively voracious desire for 38-year-old is as surprised as anyone by the short-form content. manic show’s longevity. And Robot Chicken’s snickering snippets “It’s super surreal,” marvelled the upbeat were the perfect fit. Green in a recent telephone interview. It was a coincidence that looked like “Because this was just never meant to prescience, Green says. be something that actually was a show, let “Isn’t that weird? It makes us look like alone a series, let alone a long-running se- we really knew what the hell what we were ries. This was such a side project. This was talking about,” he said with a laugh. -

RAM Lawnmower Dog Net Draft 11 28 12.Fdx

"Lawnmower Dog" By Ryan Ridley Network Draft 11/28/12 All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Cartoon Network Inc./ Turner Broadcasting System. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means, or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without prior written consent of The Cartoon Network Inc./ Turner Broadcasting System. Disposal of the script copy does not alter any of the restrictions set forth above. RICK & MORTY "LAWNMOWER DOG" NETWORK DRAFT (11/28/12) 1. EXT. MORTY’S HOME - ESTABLISHING - DAY INT. MORTY’S HOME - DAY JERRY is on the sofa watching TV. SUMMER is next to him, texting. Snuffles, the family dog, walks up and looks at Jerry. JERRY (to Snuffles) What? (no response) Why are you looking at me? (no response) You want to go outside? (no response) Outside? Jerry gets up, crosses the room and opens the back door. The dog watches him. JERRY (CONT’D) Outside? No response. Jerry closes the door, crosses back to the sofa and sits down. Snuffles raises a leg and pisses on the floor. JERRY (CONT’D) Are you KIDDING me?! Come ON! SUMMER (still texting) Oh my God I’m going to die. Morty runs in. MORTY What’s wrong? JERRY Your idiot dog! MORTY Oh, he didn’t mean it! Did you Snuffles? You didn’t mean it, you’re a good boy! Good dog! JERRY Don’t praise him now, Morty! He just pissed on the carpet! RICK & MORTY "LAWNMOWER DOG" NETWORK DRAFT (11/28/12) 2. Jerry shoves the dog’s face into the carpet.