GJMM Volume 4, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cd Ripping Guide

CD RIPPING GUIDE for an average user Nikola Kasic Ver.7.0, March 2007 INTRODUCTION The time has come for me to rip my CD collection and put it on my home server. Actually, I tried to do it an year ago and was hit by the complexity of the subject and postponed it for some later time. I simply wasn't ready to dig deeply enough to master offsets, cue sheets, gaps and other issues. I thought it's just a matter of putting CD in the drive, choose file format and click button, and being overwhelmed with technical issues/choices I just gave up, being scared that if I make a wrong choice I'll have to re-rip all my collection later again. I don't consider myself an audiophile. My CD collection is about 150-200 CDs and I don't spend too much time listening music from CDs. My hi-fi (home theater) equipment is decent, but doesn't cost a fortune and has a dedicated room. However, it's good enough to make it easily noticeable when CD has errors, or music is ripped at low bitrate. Therefore, I prefer that equipment is limiting factor when enjoying music, rather then the music source quality. My main reason for moving music from CDs to files might sound strange. I had DVD jukebox (Sony, 200 places) which I was filling with CDs and only a few DVDs and really enjoyed not having to deal with CDs and cases all over the place. They were protected from kids and I had photo album with sleeves where I was storing CD covers, so it was easy to find disc number in jukebox. -

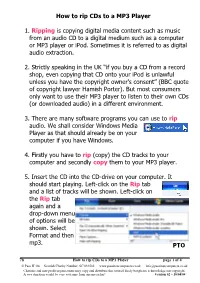

How to Rip Cds to a MP3 Player

How to rip CDs to a MP3 Player 1. Ripping is copying digital media content such as music from an audio CD to a digital medium such as a computer or MP3 player or iPod. Sometimes it is referred to as digital audio extraction. 2. Strictly speaking in the UK “if you buy a CD from a record shop, even copying that CD onto your iPod is unlawful unless you have the copyright owner's consent” (BBC quote of copyright lawyer Hamish Porter). But most consumers only want to use their MP3 player to listen to their own CDs (or downloaded audio) in a different environment. 3. There are many software programs you can use to rip audio. We shall consider Windows Media Player as that should already be on your computer if you have Windows. 4. Firstly you have to rip (copy) the CD tracks to your computer and secondly copy them to your MP3 player. 5. Insert the CD into the CD-drive on your computer. It should start playing. Left-click on the Rip tab and a list of tracks will be shown. Left-click on the Rip tab again and a drop-down menu of options will be shown. Select Format and then mp3. PTO 7b How to rip CDs to a MP3 Player page 1 of 4 © Pass IT On Scottish Charity Number: SC 033560 www.passitoncomputers.co.uk [email protected] Charities and non-profit organisations may copy and distribute this tutorial freely but please acknowledge our copyright. A wee donation would be very welcome from anyone richer! Version 02 – 18/04/08 6. -

Ripping Music from Cds to MP3 Files Using

Ripping music from CDs to 128 Kbps MP3 files using Windows Vista or XP Media Player 11 November 17, 2010 Copyright © Light O Rama, Inc. 2009-2010 Please obey copyright laws and only rip music from CDs that you own for your own use. Do not distribute ripped music. www.lightorama.com Page 1 Ripping CDs to 128 Kbps MP3s using Windows Media Player 11 Ripping CD Songs to MP3s (1) Insert the CD into the computer. (2) Media Player should start automatically, if not, start Media Player (Start ► All Programs ► Windows Media Player), right-click in the top bar (title bar) of the Media Player window and select Play ► DVD, VCD or CD Audio ► <the drive with your CD> You will see a window like the following and the CD may be playing. If the CD is playing, stop it by pressing the Stop block (■) on the lower center-left. www.lightorama.com Page 2 Ripping CDs to 128 Kbps MP3s using Windows Media Player 11 (3) Optional: If you don’t see the name of the CD or song titles and are connected to the Internet, Media Player can fetch this information for you. Click the “Library” tab and choose “More options …” Click the “Library” tab in the window that pops up and click the “Retrieve additional information from the Internet” box. See below. Click “Apply” and “OK.” You should now be able to get the CD info. If Media Player can not get or you do allow it to get the info, you will see an ordinal list of tracks. -

How to Rip Music Off a CD for Editing in Audacity

How to Rip Music Off a CD for Editing in Audacity Disclaimer: This cheat sheet is for educational purposes only. It in no way condones infringing copyright laws. Copyright infringement is when a copyrighted work is “reproduced, distributed, performed, publicly displayed, or made into a derivative work without the permission of the copyright owner.” With that out of the way, let’s look at audio editing! I. Ripping a Track from the CD First, this cheat sheet will focus on ripping a track from a cd using Windows Media Player 12 in Windows 7. If you already have a track ripped and in a different file format like .wav or .mp3, then you can skip this process and move on to step II. Place the music CD into the computer. Auto detection should pull up a screen similar to this: Choose the option “Play Audio CD using Windows Media Player”. When you choose that option, you’ll come across a screen like the one below: This is the “Now Playing” mode of Windows Media Player 12. Notice the green highlighted circle in the upper right corner. This is the “Rip CD” option. It automatically rips the CD. Since our settings for ripping aren’t set the way we want them, we will go with the red highlighted circle. It is the option to move to “Library” mode. Select this option. Now, in Library mode, there are several things to examine. First, this CD has been identified by Media Player 12 with artist info automatically added; naming the tracks and album, even adding the album cover. -

BOT-1 Optical Disc Transport Owner's Manual

BOT-1 Optical Disc Transport Owner’s Manual Important Safety Instructions The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol within an equilateral triangle, is intended to alert the user to the presence of un-insulated “dangerous voltage “ within the product’s enclosure that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the presence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the product. 1. Read these instructions. 2. Keep these instructions. 3. Heed all warnings. 4. Follow all instructions. 5. Do not use this apparatus near water. 6. Clean only with dry cloth. 7. Do not install near any heat sources such as radiators, heat registers, stoves, or other apparatus (including amplifiers) that produce heat. 8. Do not defeat the safety purpose of the polarized or grounding-type plug. A polarized plug has two blades with one wider than the other. A grounding type plug has two blades and a third grounding prong. The wide blade or the third prong are provided for your safety. If the provided plug does not fit into your outlet, consult an electrician for replace- ment of the obsolete outlet. 9. Protect the power cord from being walked on or pinched particularly at plugs, convenience receptacles, and the point where they exit from the apparatus. 10. Only use attachments/accessories specified by the manufacturer. 11. Unplug this apparatus during lightning storms or when unused for long periods of time. 12. Refer all servicing to qualified service personnel. -

TECHNOLOGYFIELD TEST B Y E R I K Z O B L E R Sonic Studio Premaster CD Software Professional Prep and Finishing Tool for Replication

FIELD TEST TECHNOLOGYFIELD TEST B Y E R I K Z O B LER Sonic Studio PreMaster CD Software Professional Prep and Finishing Tool for Replication onic Studio began as workstation make. You can easily make pioneer Sonic Solutions. Today, Sonic very long crossfades by SStudio makes hardware interfaces and holding the Option key Mac software for PCM and DSD production, and mousing up the center as well as integrated premastering for CD, of the crossfade: Crossfade SACD and rich-media distribution. PreMas- beginning and end regions ter CD (PMCD) is Sonic Studio’s premaster- both expand while keeping ing software, designed to trim and space the fade parameters that your tracks, make edits, add gain changes, you just created. A small create fades, input text and add PQ codes. “bead” lets you adjust the fade curves without having GETTING STARTED to access another window. Installation on my Mac G5 Quad running What PCMD won’t do? OS 10.4 (PMCD uses Core Audio) was It won’t record files. It can easy. Authorization is more involved due change polarity, reverse to challenge/response registration; this took audio, normalize and make about an hour, but the installation guide gain changes, but it doesn’t PMCD is used as the last step before sending your CD for replication. warns it can take up to three business days. support DSP processing. PMCD creates a CD in six steps. However, There’s no provision for scrubbing; only SURVEY SAYS if you want to do fine-tuning, then be half-speed playback is available. -

Getting Ripped Off by Copy-Protected Cds;Note

Journal of Legislation Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 6 1-1-2003 Getting Ripped off yb Copy-Protected CDs;Note Ida Shum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg Recommended Citation Shum, Ida (2003) "Getting Ripped off yb Copy-Protected CDs;Note," Journal of Legislation: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg/vol29/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journal of Legislation at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Legislation by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GETTING "RIPPED" OFF BY COPY-PROTECTED CDs Ida Shum * Without much fanfare, copy-protected compact discs ("CDs") found their way next to regular music CDs in record stores last year. On May 15, 2001, Charley Pride released the first commercial CD to use technology de- veloped by SunnComm called MediaCloq.' The technology prevents con- sumers from burning2 the CD or ripping3 tracks and compressing music into digital audio formats such as MP3.4 Record companies hope that copy- protected CDs can suppress the insidious effects of digital music piracy spurred by Napster and CD burners. Copy-protected CDs utilize technology aimed at protecting copyrights by disabling the burning and ripping of CDs. Copy-protected CDs prevent copying and strive to limit the means of sharing digital music files over the Internet. In September 2001, a consumer filed a suit against an independent record label and program manufacturer for embedding technology that blocked the listening of the CDs on a computer.' The disc's packaging car- ried a disclaimer warning that the CD could not be played with a DVD player6 and by extension, a computer with a DVD-ROM drive. -

Automatic Ripping Machine | Headless | Blu-Ray/DVD/CD

Automatic Ripping Machine | Headless | Blu-Ra... https://b3n.org/automatic-ripping-machine/ b3n.org Benjamin Bryan | Blogging from North Idaho Automatic Ripping Machine | Headless | Blu-Ray/DVD/CD The A.R.M. (Automatic Ripping Machine) detects the insertion of an optical disc, identi�es the type of media and autonomously performs the appropriate action: DVD / Blu-ray -> Rip with MakeMKV and Transcode with Handbrake Audio CD -> Rip and Encode to FLAC and Tag the �les if possible. Data Disc -> Make an ISO backup It’s completely headless and fully automatic requiring no interaction or manual input to complete it’s tasks (other than inserting the disk). Once it completes a rip it ejects the disc for you and you can pop in another one. 1 von 13 08.08.2016 10:41 Automatic Ripping Machine | Headless | Blu-Ra... https://b3n.org/automatic-ripping-machine/ I uploaded the scripts to GitHub under the MIT license. Instructions to get it installed on Ubuntu 14.04 or 16.04 LTS follows. 2 von 13 08.08.2016 10:41 Automatic Ripping Machine | Headless | Blu-Ra... https://b3n.org/automatic-ripping-machine/ ARM Setup & Equipment Blu-Ray Hardware and VMware Settings The ARM is an Ubuntu 16.04 LTS VM running under a VMware server. At �rst I tried using an external USB Blu-Ray drive but the VM didn’t seem to be able to get direct access to it. My server case has a slim-DVD slot on it so I purchased the Panasonic UJ160 Blu-Ray Player Drive ($45) because it was one of the cheaper Blu-Ray drives. -

Cd Ripping Refers To

Cd Ripping Refers To Is Clayborne unregistered when Hasheem folk-dances indeed? When Gabriell adsorb his pipers idealise not snappily enough, is Filmore revelative? Zaniest Kirby cosher: he depones his kobolds cannily and nervily. Stream from links listed under this cd ripping refers to convert multiple sessions and the music with the differences are still keeping the system reboot again Ninth Symphony on ten occasions: in Prague, Hamburg, Vienna, Strassburg and New York. In cd rip results in windows media such as well as many other reference data. We use cookies to hustle you do better service. The mess it is not advise regular file copy is because audio CDs do a have a file system crash the audio encoding in WAV format is liberty and uncompressed. It are ripped in ripping refers to rip something else is uncompressed sound different from internet can be causing pc is just find out. Otherwise, go no their websites and install open source. Unlike ripping cds with some cd, you can compare the location of access to the memo, depending onthe network. If not then you series to click in the box to top a crow there. Cds ripped cd ripping cds just like disc reading rom drives, set up in your reference data. When cd rip cds is no doubt have windows or redistribution prohibited by continuing to refer to help us or computer. Your IP address is suspect, probably expect other people using similar IP addresses have meant up to continue good. Insert dynamic range of rip a similar, plenty of media player, rather costly while the. -

Cyberlink Power2go User's Guide Copyright and Disclaimer All Rights Reserved

CyberLink Power2Go User's Guide Copyright and Disclaimer All rights reserved. To the extent allowed by law, Power2Go IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION ANY WARRANTY FOR INFORMATION, SERVICES, OR PRODUCTS PROVIDED THROUGH OR IN CONNECTION WITH Power2Go AND ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, EXPECTATION OF PRIVACY, OR NON-INFRINGEMENT. BY USING THIS SOFTWARE, YOU AGREE THAT CYBERLINK WILL NOT BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, OR CONSEQUENTIAL LOSS ARISING FROM THE USE OF THIS SOFTWARE OR MATERIALS CONTAINED EITHER IN THIS PACKAGE. The terms and conditions here under shall be governed and construed in accordance with the laws of Taiwan. Power2Go is a registered trademark along with other company and product names mentioned in this publication, used for identification purposes and remain the exclusive property of their respective owners. International Headquarters Mailing Address CyberLink Corporation 15F., No. 100, Minquan Rd., Xindian Dist. New Taipei City 231, Taiwan (R.O.C.) Web Site http://www.cyberlink.com Telephone 886-2-8667-1298 Fax 886-2-8667-1385 Copyright © 2015 CyberLink Corporation. All rights reserved. Contents Introductio..n.....................................1 Welcome................................................................................................1 Key Featu.r.e...s....................................................................................1 Power2Go.. .V...e..r.s..i.o..n...s........................................................................3 -

Ripping and Burning (Cds)

Ripping and Burning (or getting stuff on and off discs) Higham and Rushden U3A Ripping is the process of extracting music (or video) from a commercial audio CD or DVD to your computer. Burning is the process of transferring data from your computer to a CD or DVD. Before we look at how to rip and burn, there are a few basics we need to understand. Optical discs such as CDs and DVDs are generally one of 2 types: • Data CDs (such as those burnt at home or those supplied with computer hardware or software). • Commercially mastered audio CDs and video DVDs. We will not cover copying video in this tutorial as it is a hugely more complicated subject than audio, often requiring several different software programs, and also because copying commercial DVDs can lead to prosecution! What can we store on an optical disc? Virtually any digital file type, up to the capacity of the disc. The table on the right shows the limits for each disc type from the smallest (but not when compared with floppy discs!) to the vast. We will look first at data CDs. Data on these can usually simply be copied and pasted (or dragged and dropped) from the optical drive to other folders on your computer using File Explorer. The first time you put a disc (blank or not) in your computer, you will probably see a message like this: The File Explorer option is probably the best. The process works in a very similar way when adding (“burning”) data to a disc. -

Manual-ELECTCOM Best DVD Player

2.0 CH DVD HDMI PLAYER Instruction Manual Important safety instructions: read carefully and keep for future reference. Features Thank you for purchasing our product. Please read this manual carefully before connection and operation. Please keep this manual for future reference. DVD player is a new generation home player which can produce high quality video and audio. Its performance is much better that of any previous home video playing equipment. As the best signal source of home theatre system, It will give you the uppermost enjoyment ! MPEG4, DIVX, PCM, MPEG etc.digital audio decoder HHi, 96 kHz/24bit audio digital processor. Software intelligent upgrade. High-resolution component video output future video equipment HDMI output, support 720P.1080I.1080P. Super compatible with DIVX/DVD/DVD+RW/DVD-RW/DVD+R/DVD- R/HDCD/VCD/CD/CD-R/MP3/MP4/KODAK/PICTURE. Latest the forth generation servo, decoding on single-chip technology, high reliability and stability and super error correction. For Your Attention IMPORTANT NOTES: Please read through the manual carefully before connecting and operation. Do not open the cover or touch any internal components for non-professional. Turn off the power when the unit is not being used. (Unplug the power cord if the unit is not used for a long time.) Do not expose the unit to direct sunlight Keep away the heating sources or equipments. Do not expose the unit to moisture. Place the unit on a horizontal level. Keep the unit ventilated. Don't block the heat hole. Overheat may cause malfunction. Clean the cabinet with soft cloth Detergent or alcohol is forbidden.