Reopening Gaffurius's Libroni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pietro Aaron on Musica Plana: a Translation and Commentary on Book I of the Libri Tres De Institutione Harmonica (1516)

Pietro Aaron on musica plana: A Translation and Commentary on Book I of the Libri tres de institutione harmonica (1516) Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Joseph Bester, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Charles Atkinson Burdette Green Copyright by Matthew Joseph Bester 2013 Abstract Historians of music theory long have recognized the importance of the sixteenth- century Florentine theorist Pietro Aaron for his influential vernacular treatises on practical matters concerning polyphony, most notably his Toscanello in musica (Venice, 1523) and his Trattato della natura et cognitione de tutti gli tuoni di canto figurato (Venice, 1525). Less often discussed is Aaron’s treatment of plainsong, the most complete statement of which occurs in the opening book of his first published treatise, the Libri tres de institutione harmonica (Bologna, 1516). The present dissertation aims to assess and contextualize Aaron’s perspective on the subject with a translation and commentary on the first book of the De institutione harmonica. The extensive commentary endeavors to situate Aaron’s treatment of plainsong more concretely within the history of music theory, with particular focus on some of the most prominent treatises that were circulating in the decades prior to the publication of the De institutione harmonica. This includes works by such well-known theorists as Marchetto da Padova, Johannes Tinctoris, and Franchinus Gaffurius, but equally significant are certain lesser-known practical works on the topic of plainsong from around the turn of the century, some of which are in the vernacular Italian, including Bonaventura da Brescia’s Breviloquium musicale (1497), the anonymous Compendium musices (1499), and the anonymous Quaestiones et solutiones (c.1500). -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King's Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Sixteenth centuary accidentals and ornamentation in selected motets of Josquin Desprez: a comparativbe study of the printed intabulations with the vocal sources Erictoft, Robert The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 g c1Yr, c-rj, prLr Ac.fl IN SELECTED MOTETS OF ,JOSQUIN DESPREZ: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF T}LE PRINTED INTABULATIONS WITH THE VOCAL SOURCES VOLUME I by ROBERT ERIC TOFT Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy King's College University of London 198 ABSTRACT One of the major problems in Renaissance music scholarship has been to establish a precise understanding of the structure and development of pretonal polyphony. -

Gaspar Van Weerbeke New Perspectives on His Life and Music Gaspar Van Weerbeke New Perspectives on His Life and Music

Gaspar van Weerbeke New Perspectives on his Life and Music Gaspar van Weerbeke New Perspectives on his Life and Music edited by Andrea Lindmayr-Brandl and Paul Kolb Centre d’études supérieures de la Renaissance Université de Tours / du Collection « Épitome musical » dirigée par Philippe Vendrix Editorial Committee: Hyacinthe Belliot, Vincent Besson, Camilla Cavicchi, David Fiala, Christian Meyer, Daniel Saulnier, Solveig Serre, Vasco Zara Advisory board: Andrew Kirkman (University of Birmingham), Yolanda Plumley (University of Exeter), Jesse Rodin (Stanford University), Richard Freedman (Haverford College), Massimo Privitera (Università di Palermo), Kate van Orden (Harvard University), Emilio Ros-Fabregas (CSIC-Barcelona), omas Schmidt (University of Hudders eld), Giuseppe Gerbino (Columbia University), Vincenzo Borghetti (Università di Verona), Marie-Alexis Colin (Université Libre de Bruxelles), Laurenz Lütteken (Universität Zürich), Katelijne Schiltz (Universität Regensburg), Pedro Memelsdor¦ (Chercheur associé, Centre d'études supérieures de la Renaissance–Tours), Philippe Canguilhem (Université de Toulouse Le Mirail) Layout: Vincent Besson Research results from: Auª rian Science Fund (FWF): P¬®¯°±. Published with the support of Auª rian Science Fund (FWF): PUB ®°³-G¬®. Cover illu ration: Image ®°³´¬µ°¯ © Giuseppe Anello – Dreamª ime.com Coat of arms of Ludovico Maria Sforza ISBN 978-2-503-58454-6 e-ISBN 978-2-503-58455-3 DOI 10.1484/M.EM-EB.5.117281 ISSN 2565-8166 E-ISSN 2565-9510 D/// Dépôt légal : F © ¸¹º, Brepols Publishers n.v., Turnhout, Belgium – CESR, Tours, France. Open access: Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unpor- ted License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Printed in the E. -

Books About Music in Renaissance Print Culture: Authors, Printers, and Readers

BOOKS ABOUT MUSIC IN RENAISSANCE PRINT CULTURE: AUTHORS, PRINTERS, AND READERS Samuel J. Brannon A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Anne MacNeil Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter John L. Nádas Philip Vandermeer © 2016 Samuel J. Brannon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Samuel J. Brannon: Books about Music in Renaissance Print Culture: Authors, Printers, and Readers (Under the direction of Anne MacNeil) This study examines the ways that printing technology affected the relationship between Renaissance authors of books about music and their readers. I argue that the proliferation of books by past and then-present authors and emerging expectations of textual and logical coherence led to the coalescence and formalization of music theory as a field of inquiry. By comparing multiple copies of single books about music, I show how readers employed a wide range of strategies to understand the often confusing subject of music. Similarly, I show how their authors and printers responded in turn, making their books more readable and user-friendly while attempting to profit from the enterprise. In exploring the complex negotiations among authors of books about music, their printers, and their readers, I seek to demonstrate how printing technology enabled authors and readers to engage with one another in unprecedented and meaningful ways. I aim to bring studies of Renaissance music into greater dialogue with the history of the book. -

Jubal, Pythagoras and the Myth of the Origin of Music with Some Remarks Concerning the Illumination of Pit (It

Philomusica on-line 16 (2017) Jubal, Pythagoras and the Myth of the Origin of Music With some remarks concerning the illumination of Pit (It. 568) Davide Daolmi Università degli Studi di Milano [email protected] § Alla fine del Trecento l’iconografia § At the end of the fourteenth century della Musica mostra una forma the iconography of Music shows a complessa basata sul mito del primo complex morphology based on the padre fondatore dell’arte musicale. La myth of the first founding father of the sua raffigurazione più sofisticata appa- musical art. Its most sophisticated re nella miniatura d’apertura di Pit image appears in the opening (Parigi, Bibl. Nazionale, It. 568), uno illumination of Pit (Paris, Bibl. dei più importanti manoscritti di Ars Nationale, It. 568), one of the most Nova italiana. important manuscripts of the Italian Nel riconsiderare la bibliografia Ars Nova. esistente, la prima parte dell’articolo After reviewing the existing biblio- indaga il contesto culturale che ha graphy, the first part of the article prodotto la miniatura, per poi, nella traces the cultural context that seconda, ripercorrere l’intera storia del produced this illumination. The mito, la sua tradizione biblica (Iubal), il second part reconstructs the whole suo corrispondente pagano (Pitagora), history of the myth of the origin of il rapporto con il mito della translatio music, its biblical tradition (Jubal), its studii (le colonne della conoscenza), e pagan equivalent (Pythagoras), their la sua forma complessa adottata a association with the myth of translatio partire dal XII secolo. Il modello studii (the pillars of knowledge), and iconografico fu concepito in Italia nel its syncretic form adopted from the Trecento e la forma ormai matura twelfth century onward. -

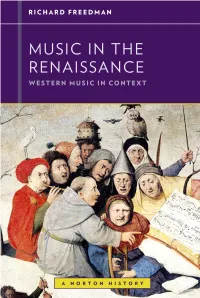

MUSIC in the RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Richard Freedman Haverford College n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY Ƌ ƋĐƋ W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program—trade books and college texts— were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: Bonnie Blackburn Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics-Fairfield, PA A catalogue record is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-393-92916-4 W. -

Reopening Gaffurius's Libroni

Agnese Pavanello, Introduction Daniele V. Filippi, The Making and the Dating of the Gaffurius Codices: Archival Evidence and Research Perspectives Martina Pantarotto, ‘Scripsi et notavi’: Scribes, Notators, and Calligraphers in the Workshop of the Gaffurius Codices Daniele V. Filippi, Gaffurius’s Paratexts: Notes on the Indexes of Libroni 1–3 Cristina Cassia, Gaffurius at the Mirror: The Internal Concordances of the Libroni Agnese Pavanello, The Non-Milanese Repertory of the Libroni: A Potential Guide for Tracking Musical Exchanges Reopening Gaffurius’s Libroni Gaffurius’s Reopening Reopening Gaffurius’s Libroni Studi e Saggi edited by Agnese Pavanello . 40 . € 35 LIM Libreria Musicale Italiana LIM Editrice srl Via di Arsina 296/f - 55100 LUCCA Tel. 0583 394464 – Fax 0583394469 / 0583394326 Libreria Musicale Italiana [email protected] www.lim.it Questo file è personale e non cedibile a terzi senza una specifica autorizzazione scritta dell’editore. I nostriThis PDF file sono is perment esclusivofor strictly uso personal personale. use. PossonoIt cannot essere be transferred copiati senza without restrizioni a written sugli permission apparecchi by thedell’u - tente publisher.che li ha acquistati (computer, tablet o smartphone). Possono essere inviati come titoli di valutazione scientifica e curricolare, ma non possono essere ceduti a terzi senza una autorizzazione scritta dell’editore e non possono essere stampati se non per uso strettamente individuale. Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Su academia.edu o altri portali simili (siti repository open access o a pagamento) è consentito pubblicare sol- tanto il frontespizio del volume o del saggio, l’eventuale abstract e fino a quattro pagine del testo. La LIM può fornire a richiesta un pdf formattato per questi scopi con il link alla sezione del suo sito dove il saggio può essere acquistato in versione cartacea e/o digitale. -

Instruments of Music Theory

Instruments of Music Theory The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Rehding, Alexander. 2016. "Instruments of Music Theory." Music Theory Online 22, no. 4. Published Version http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.4/mto.16.22.4.rehding.html Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34391750 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUTHOR: Rehding, Alexander TITLE: Instruments of Music Theory KEYWORDS: History of Music Theory, Critical Organology, Sound Studies, Acoustics, Epistemic Thing, Pythagoras, Gaffurius, Vicentino, Cowell, monochord, archicembalo, siren, rhythmicon. ABSTRACT: This article explores musical instruments as a source for the historical study of music theory. The figure of Pythagoras and his alleged penchant for the monochord offers a way into this exploration of the theory-bearing dimensions of instruments. Musicians tend to think of instruments primarily in terms of music-making, but in other contexts instruments are, more broadly, tools. In the context of scientific experimentation, specifically, instruments help researchers come to terms with “epistemic things”—objects under scrutiny that carry specific (but as yet unknown) sources of knowledge within them. Aspects of this experimental practice can productively be transferred to the study of music theory and are explored in a two test cases from different periods of musical theorizing (and instrument building): Nicola Vicentino’s archicembalo from mid-sixteenth century Italy, and Henry Cowell’s rhythmicon from the early-twentieth century America. -

Jacopo Tintoretto's Female Concert

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, May 2016, Vol. 6, No. 5, 478-499 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.05.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Jacopo Tintoretto’s Female Concert: The Realm of Venus Liana De Girolami Cheney Università di Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy This study aims to visualize Giorgio Vasari’s statement in discussing Jacopo Tintoretto’s Female Concert of 1576-86, now at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden (see Figure 1). Two conceits (concetti) are considered in analyzing Tintoretto’s female imagery: (1) a fanciful invention of musica extravaganza; and (2) a Venetian allegory of bellezza. The first part of the essay discusses the provenance of the painting and the second part presents an iconographical interpretation of the imagery. This essay also focuses on the iconography of the painting based on viewing the subject and does not postulate on its iconography based on disappeared paintings or on a speculative decorative cycle on the theme of Hercules. Relying on well-documented research on music in Venice, on Mannerist practices, and on art theories during Tintoretto’s life, some intriguing observations are made about the painting. Keywords: beauty, music, iconography, alchemy, interpretation, mythology, muses, Neoplatonism, Venus “E vera cosa che la musica ha la sua propria sede in questa città” (“It is true that music has its own official seat in this city [Venice]”) —Francesco Sansovino Venetia città nobilissima (Venice, 1581)1 Introduction In Venice in 1566, Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), a Florentine artist and writer, met the Venetian painter and musician, Jacopo Comin Robusti, known as Tintoretto (1518-94). -

GAFFURIUS's PRACTICA MUSICAE: ORIGIN and CONTENTS* Recent

GAFFURIUS'S PRACTICA MUSICAE: ORIGIN AND CONTENTS* CLEMENT A. MILLER Recent studies of the life and works of Franchinus Gaffurius state that his Practica Musicae, consisting of four books, was written at Monticelli and Bergamo between 1481 and 1483, although the work was not published until 1496 1 . There are two principal reasons for this belief, one of which is the fact that Gaffurius's biographer, Panteleone Meleguli, informs us that Gaffurius began the Practica at Monticelli 2 . The other is based on a manu script of the Practica, dated 148 7, which was apparently a copy of an auto graph manuscript of the Practica left at the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo 3 . Gaffurius was chapel master at this church during 1483, but the following year he assumed the same position at the Cathedral in Milan. The 148 7 manuscript copy of his Practica is the only handwritten copy that is still extant 4 . Examination of the manuscript supports Meleguli's statement concern ing the inception of Practica Musicae 5, but it does not uphold the modern view that it was completed in 1483. In fact, it indicates quite clearly that some of the Practica was written at Milan, and that the four books of the printed edition did not originally form a single treatise but were only later to assume this form. The manuscript copy of 1487 was made by a Carmelite friar, Alexan der Assolari. On fol. 106r he wrote: Hoc opusculum scriptum et notatum fuit per Fratrem Alexandrum de Assolariis ... in conventu nostro berga mi .. -

Adrian Willaert's "Musica Nova" Selected Motets: Editions and Commentary

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1993 Adrian Willaert's "Musica Nova" Selected Motets: Editions and Commentary. (Volumes I and II). Bradley Leonard Almquist Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Almquist, Bradley Leonard, "Adrian Willaert's "Musica Nova" Selected Motets: Editions and Commentary. (Volumes I and II)." (1993). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5556. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5556 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Edited by Macmillan Publishers Limited, London Grove's Dictionaries of Music Inc., Washington, Dc Peninsula Publishers Limited, Hong Kong

EDITED BY MACMILLAN PUBLISHERS LIMITED, LONDON GROVE'S DICTIONARIES OF MUSIC INC., WASHINGTON, DC PENINSULA PUBLISHERS LIMITED, HONG KONG © Macmillan Publishers Limited 1980 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. GENERAL ABBREVIATIONS vii First Edition of A Dictionary of Music and Musicians, planned and edited by SIR GEORGE GROVE, DCL, in BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ABBREVIATIONS Xl four volumes, with an Appendix edited by J. A. Fuller Maitland, and an Index by Mrs Edmond Wodehouse, 1878, 1880, 1883, 1890. LIBRARY SIGLA XIV Reprinted 1890, 1900 A NOTE ON THE USE OF THE DICTIONARY xxxii Second Edition, edited by J. A. FULLER MAITLAND, in five volumes, 1904-10 THE DICTIONARY, VOLUME SEVEN: Third Edition, edited by H. C. COLLES, in five volumes, 1927 Fourth Edition, edited by H. C. COLLES, in five volumes, with Supplementary Volume, 1940 Fuchs-Gyuzelev 1 Fifth Edition, edited by ERIC BLOM, in nine volumes, 1954: with Supplementary Volume, 1961 Reprinted 1961, 1973, 1975 ILLUSTRATION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 873 American Supplement, edited by W ALDO SELDEN PRATT, in one volume, 1920 Reprinted, with new material, 1920, 1928, 1935, 1952 The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by STANLEY SADIE, in twenty volumes, 1980 Published by Macmillan Publishers Limited, London. This edition is distributed outside the United Kingdom and Europe by Peninsula Publishers Limited, Hong Kong, a member of the Macmillan Publishers Group, and by its appointed agents. In the United States of America and Canada, Peninsula Publishers have appointed Grove's Dictionaries of Music Inc., Washington, DC, as sole distributor.