Provision for Gifted Children in Primary Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINALIST DIRECTORY VIRTUAL REGENERON ISEF 2020 Animal Sciences

FINALIST DIRECTORY VIRTUAL REGENERON ISEF 2020 Animal Sciences ANIM001 Dispersal and Behavior Patterns between ANIM010 The Study of Anasa tristis Elimination Using Dispersing Wolves and Pack Wolves in Northern Household Products Minnesota Carter McGaha, 15, Freshman, Vici Public Schools, Marcy Ferriere, 18, Senior, Cloquet, Senior High Vici, OK School, Cloquet, MN ANIM011 The Ketogenic Diet Ameliorates the Effects of ANIM002 Antsel and Gretal Caffeine in Seizure Susceptible Drosophila Avneesh Saravanapavan, 14, Freshman, West Port melanogaster High School, Ocala, FL Katherine St George, 17, Senior, John F. Kennedy High School, Bellmore, NY ANIM003 Year Three: Evaluating the Effects of Bifidobacterium infantis Compared with ANIM012 Development and Application of Attractants and Fumagillin on the Honeybee Gut Parasite Controlled-release Microcapsules for the Nosema ceranae and Overall Gut Microbiota Control of an Important Economic Pest: Flower # Varun Madan, 15, Sophomore, Lake Highland Thrips, Frankliniella intonsa Preparatory School, Orlando, FL Chunyi Wei, 16, Sophomore, The Affiliated High School of Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, ANIM004T Using Protease-activated Receptors (PARs) in Fujian, China Caenorhabditis elegans as a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Inflammatory Diseases ANIM013 The Impacts of Brandt's Voles (Lasiopodomys Swetha Velayutham, 15, Sophomore, brandtii) on the Growth of Plantations Vyshnavi Poruri, 15, Sophomore, Surrounding their Patched Burrow Units Plano East, Senior High School, Plano, TX Meiqi Sun, 18, Senior, -

“If You Talk, You Are Just Talking. If I Talk, Is That Bragging?”

“If you talk, you are just talking. If I talk, is that bragging?” PERSPECTIVES OF PARENTS WITH YOUNG GIFTED CHILDREN IN NEW ZEALAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Education in the University of Canterbury by Lakshmi Chellapan University of Canterbury 2012 Table of Contents Dedication ..................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgement ......................................................................................................................... vi Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ vii Glossary .......................................................................................................................................... x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Context of the study ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1. Malaysian Gifted Curriculum (PERMATA PINTAR) ............................................................ 2 1.1.2 Overview of Malaysian Early Childhood Education (PERMATA PINTAR) .......................... 2 1.1.3. Who can participate in this camp? ..................................................................................... 4 1.1.4. Researcher’s -

Effects of Enrichment Programs on the Academic Achievement of Gifted

Journal for the Education of the Young Scientist and Giftedness 2014, Volume 2, Issue 2, 22-27 Original Research Article Effects of Enrichment Programs on the Academic Achievement of Gifted and Talented Students ABSTRACT: The aim of the study was to explore the effect of enrichment programs on Suhail Mahmoud AL- the academic achievement of gifted and talented students. The sample of the study ZOUBI, Asisst. Prof. Dr., Department of Special consisted of (30) gifted and talented students studying at Al-Kourah Pioneer Center for Education, Faculty of gifted and talented students (APCGTS), Jordan. An achievement test was developed and Education, Najran applied on the sample of the study as a pretest and posttest. The results showed the University, Kingdom effects of enrichment programs at APCGTS on improving the academic achievement of of Saudia Arabia. gifted and talented students. E-mail: Keywords: gifted & talented students; enrichment; academic achievement; Pioneer [email protected] om Centers Received: Spt 25, 2014 Accepted: Oct 13, 2014 © 2014 Journal for the Education of the Young Scientist and Giftedness ISSN: 2147-9518, http://jeysg.org Al-Zoubi 23 INTRODUCTION The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has done The gifted and talented students (GTS) a great effort for the GTS by founding receiving extra educational services, advanced educational programs that take care of them; curriculum, additional courses, better teachers, some of these programs are: Jubilee School, King and more challenging learning environments than Abdulla schools -

Intel ISEF 2013 Special Award Organizations Ceremony May 16, 2013 Phoenix, Arizona

Intel ISEF 2013 Special Award Organizations Ceremony May 16, 2013 Phoenix, Arizona Society for Science & the Public, in partnership with the Intel Foundation, announced the Special Award Organization winners of the Intel ISEF 2013. Student winners are ninth through twelfth graders who earned the right to compete at the Intel ISEF 2013 by winning a top prize at a local, regional, state or national science fair. Acoustical Society of America The Acoustical Society of America is the premier international scientific society in acoustics, dedicated to increasing and diffusing the knowledge of acoustics and its practical applications. First Award of $1,500; in addition, the student's school will be awarded $500 and the student's mentor will be awarded $250. PH002 Misbehaving Waves: The SurReal Thing Myles Withay Mitchell, 18, Limavady Grammar School, Limavady, Northern Ireland Second Award of $500; in addition, the student's school will be awarded $200, and the student's mentor will be awarded $100. EE037 An "EXTRA" Sense: Ultrasound Glove Assisting Spatial Orientation of the Visually Impaired Ivan Seleznov, 17, Specialized School No. 22, Mykolaiv, Ukraine Certificate of Honorable Mention CS044 Finding Best Speaker Position Using New Algorithms to Determine Acoustic Properties of a Room Akshat Boobna, 16, Amity International School, Saket, New Delhi, India PH308 "V-shaped Wave" Generated by a Moving Object: Analyses and Experiments on Capillary Gravity Waves Tomohiko Sato, 17, Hiroshima Prefectural Fuchu Senior High School, Fuchu-shi, Japan Takahiro Yomono, 18, Hiroshima Prefectural Fuchu Senior High School, Fuchu-shi, Japan The first place award winner's school will be awarded $500 and the student's mentor will be awarded $250. -

2009 Admissions Cycle

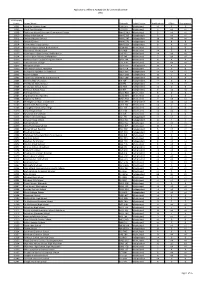

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2009 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <4 0 0 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <4 <4 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent 7 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 18 <4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 20 8 8 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 8 4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 5 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <4 0 0 10022 Queensbury Upper School, Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 <4 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 7 <4 <4 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 8 4 4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 15 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 0 0 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 7 6 10033 The School of St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 22 9 9 10035 Dean College of London N7 7QP Independent <4 0 0 10036 The Marist Senior School SL57PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 0 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 <4 <4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 0 0 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 346 306 CE 061 352 AUTHOR Mader, Wilhelm, Ed. TITLE Adult Education in the Federal Republic of Germany

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 346 306 CE 061 352 AUTHOR Mader, Wilhelm, Ed. TITLE Adult Education in the Federal Republic of Germany: Scholarly Approaches and Professional Practice. Monographs on Comparative and Area Studies in Adult Education. INSTITUTION British Columbia Univ., Vancouver. Center for Continuing Education.; International Council for Adult Education, Toronto (Ontario). REPORT NO ISBN-0-88843-192-9 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 259p.; Translation of "Weiterbildung und Gesellschaft" (University of Bremen, 1990). Translated by Martin G. Haindorff. AVAILABLE FROMPu:)lications, Centre for Continuing Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia VST 1Z1, Canada ($20). PUB TYPE Coliected Works - General (020) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) -- Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Developed Nations; Educational Development; *Educational History; Educational Principles; *Educational Theories; Experiential Learning; Feminism; Foreign Countries; Humanities; Interdisciplinary Approach; Labor Education; Political Influences; Psychology; Sociology; Vocational 'Education 'IDENTIFIERS *West Germany ABSTRACT This monograph offers insight into the development of the conceptual basis, scholarly inquiry, and professional practice of adult education in West Germany from the end of World War II to the German reunification. Introductory materials are an "Introduction" (Wilhelm Mader) and "Translator's Note and Acknowledgements" (Nartin Haindorff). Three papers in Part I deal with -

Table of Contents

NOVEMBER 20–23 | SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Welcome to ASOR’s 2019 Annual Meeting 2–6 History of ASOR 7 Program-at-a-Glance 10–12 Business Meetings and Special Events 14–15 Meeting Highlights 16 Members’ Meeting Agenda 16 Academic Program 20–49 Contents Projects on Parade Poster Session 50–51 of 2019 Sponsors and Exhibitors 52–57 2018 Honors and Awards 58 Looking Ahead to the 2020 Annual Meeting 59 Honorific and Memorial Gifts 60–61 Fiscal Year 2019 Honor Roll 62–64 Table Table ASOR’s Legacy Circle 65 2019 ACOR Jordanian Travel Scholarship Recipients 65 2019 Fellowship Recipients 66 ASOR Board of Trustees 67 ASOR Committees 68–70 Institutional Members 71 Overseas Centers 72 ASOR Staff 73 Paper Abstracts 74–194 Projects on Parade Poster Abstracts 195–204 Index of Sessions 205–207 Index of Presenters 208–214 Hotel Information 215 Meeting Mobile App and Wifi Information 216 Cover photo credit: courtesy of Joanne DiBona and Visit San Diego ISBN 978-0-89757-114-2 ASOR PROGRAM GUIDE 2019 | 1 AMERICAN SCHOOLS OF ORIENTAL RESEARCH | 2019 ANNUAL MEETING Welcome from the ASOR President, Susan Ackerman Welcome to ASOR’s 2019 Annual Meeting! We are delighted to be back at the Westin San Diego—the site of ASOR’s very successful 2014 meeting— and even more delighted to report that, in 2019, we have an even richer and more dynamic program to present to you than we did five years ago, with 60 additional papers and posters, featuring our members’ cutting-edge research about all of the major regions of the Near East and wider Mediterranean, from earliest times through the Islamic period. -

Gifted and Talented Education in New Zealand Schools: a Decade Later

Riley, T., & Bicknell, B. (2013). Gifted and talented education in New Zealand Schools: A Decade Later. APEX: The New Zealand Journal of Gifted Education, 18(1). Retrieved from www.giftedchildren.org.nz/apex. Gifted and Talented Education in New Zealand Schools: A Decade Later Tracy Riley, Massey University and Brenda Bicknell, The University of Waikato Introduction In 2004, the Ministry of Education released research investigating identification of and provisions for gifted and talented students in New Zealand Schools (Riley, Bevan-Brown, Bicknell, Carroll-Lind, & Kearney, 2004). This was landmark research: the first national study of gifted and talented education funded by the Ministry and released alongside a range of initiatives for students and those who identify and educate them in the schooling sector. The research comprised a comprehensive review of the literature, a national survey of schools, and ten case studies of best practice, with an aim of creating “a roadmap for future research and initiatives” (2004, p. 36). This earlier research concluded that while there was a growing awareness of the need for gifted and talented education, identification and provisions were both supported and impeded by professional learning and development, access to resources and support, funding, time, and cultural understandings. While giftedness and talent was defined broadly and school-based definitions were inclusive of multiple areas of abilities and qualities, many reported definitions did not embody Maori perspectives and values. Identification of gifts and talents was highly reliant on teachers and standardized forms of assessment. A preference for combining enrichment with acceleration, across a range of approaches, was desirable, but limited in implementation, with partiality towards regular classroom and withdrawal or pull-out programmes. -

¡Empieza El Colegio! P

SUMARIO SUMARIO SUMARIO 2013-14 Guía de los Mejores Colegios de España Becas y otras ayudas p. 38 Financiación y asociaciones educativas ¿Sabe cuáles son los gastos básicos que suele tener una familia en cada nivel educativo? ¿Y cómo se puede acceder a las diferentes ayudas a la educación que se ofrecen en cada comunidad autónoma?. Le indicamos dónde puede encontrar ayudas economicas para financiar los estudios de sus hijos y también las direcciones de las principales organizaciones Cómo usar la Guía p. 20 educativas en nuestro país. Todos los contenidos para elegir el mejor centro La “Guía de los Mejores Colegios de España” es una herramienta fundamental para todos aquellos padres que buscan un centro educativo de calidad. Un estudio comparativo que Acceder a la universidad p. 40 reúne toda la información que se necesita saber a la hora de elegir un centro, y que Opciones de formación superior incluye una selección de los 300 mejores colegios concertados y privados que hay en La formación superior en nuestro país ha sufrido numerosos cambios: nuevas opciones de nuestro país. Bachillerato, una nueva selectividad, grados universitarios que sustituyen a las carreras tradicionales, títulos de Formación Profesional que permiten el acceso a la universidad, nuevas enseñanzas artísticas... Conocer todas las opciones que se ofrecen es fundamental para poder Estudiar en España p. 22 ayudarles a planificar su futuro académico y profesional. Las enseñanzas básicas En los últimos años se han producido importantes cambios en nuestro sistema educativo, que aún está en proceso de transformación. Reunimos los puntos más ¡Empieza el colegio! p. -

20Th November 2015 Dear Request for Information Under the Freedom

Governance & Legal Room 2.33 Services Franklin Wilkins Building 150 Stamford Street Information Management London and Compliance SE1 9NH Tel: 020 7848 7816 Email: [email protected] By email only to: 20th November 2015 Dear Request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (“the Act”) Further to your recent request for information held by King’s College London, I am writing to confirm that the requested information is held by the university. Some of the requested is being withheld in accordance with section 40 of the Act – Personal Information. Your request We received your information request on 26th October 2015 and have treated it as a request for information made under section 1(1) of the Act. You requested the following information. “Would it be possible for you provide me with a list of the schools that the 2015 intake of first year undergraduate students attended directly before joining the Kings College London? Ideally I would like this information as a csv, .xls or similar file. The information I require is: Column 1) the name of the school (plus any code that you use as a unique identifier) Column 2) the country where the school is located (ideally using the ISO 3166-1 country code) Column 3) the post code of the school (to help distinguish schools with similar names) Column 4) the total number of new students that joined Kings College in 2015 from the school. Please note: I only want the name of the school. This request for information does not include any data covered by the Data Protection Act 1998.” Our response Please see the attached spreadsheet which contains the information you have requested. -

2013 Admissions Cycle

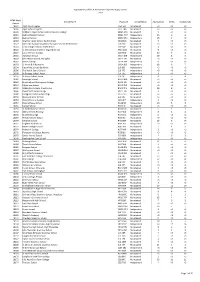

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2013 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 15 6 4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy (formerly Upper School) Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 9 <3 <3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 5 4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 18 6 6 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 8 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 18 9 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 9 5 4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 8 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon -

GRANTEES :: from 2009 to 2014

GRANT RECIPIENTS GRANTEES :: FROM 2009 to 2014 December, 2014 Funding Round Co-Location of Child & Family Social Services - $10,000.00 Purpose: To co-locate several Canterbury agencies and deliver increased support to vulnerable families. Organisations: Aviva, Family Help Trust, Barnardos New Zealand, He Waka Tapu RAW 2014 Ltd Corrections Initiative - $10,000.00 Purpose: To work with the Department of Corrections to reduce the cycle of family violence through education and mentoring of women prisoners. Organisations: RAW 2014 Ltd, Department of Corrections Future Focus Project (Phase 2) - $16,000.00 Purpose: To progress phase two of the Future Focus project. Organisations: Birthright New Zealand Incorporated Gateway to Aquatics - $4,250.00 Purpose: To enhance the outcomes already achieved with your Gateway programme by including young Muslim women. Organisations: WaterSafe Auckland Inc, Community Leisure Management, Swimming NZ, New Zealand Maritime Museum Pick Up Collaboration - $20,000.00 Purpose: To consider how best to collaboratively approach social enterprise development. Organisations: Project Lyttelton, Youth Alive Trust, SPAN Charitable Trust – trading as SkillWise, Big Brothers Big Sisters of Christchurch, Canterbury Community Business Trust, Aviva Building Our Community Together - $15,000.00 Purpose: To recruit a project coordinator to identify opportunities for research and evaluation of potential collaborations. Organisations: Merivale Community Centre, Te Tuinga Whanau, Merivale Community Garden, Employ NZ, Homes