Fishworkers' Rights Study -- Purba Medinipur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status of the Largest Dry Fish Market of East India: a Study on Egra

ISSN: 2347-3215 Volume 2 Number 5 (May-2014) pp. 54-65 www.ijcrar.com Status of the largest dry fish market of East India: A study on Egra Regulated Dry Fish Market, Egra, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal Sudipta Kumar Ghorai1*, Santosh kumar Bera1, Debanjan Jana2, Somnath Mishra3 1Department of Zoology, Egra SSB College, West Bengal, India 2Department of Biotechnology, Haldia Institute of Technology, West Bengal, India 3Department of Geography, Kalagachia Jagadish Vidyapith, West Bengal, India *Corresponding author KEYWORDS A B S T R A C T The present investigation was conducted to find out the effectiveness of Egra Dry fish market; regulated dry fish market as a marketing system in importing and exporting dry trading system; fish from different coastal areas of Bay of Bengal to different parts of India, Egra Regulated specially north east India . The market was surveyed from April 2013 to March Dry Fish Market 2014. The study area was purposively selected and the trading system was analyzed. The market operates actively once in a week. Survey question schedule was made for the collection of data. Several species of coastal and marine dried fish like patia, lahara, vola, chanda, ruli etc were commonly available in the market. Different types of businessmen are involved in the trading system like fish processor, Beparis, Aratdars, Wholesalers, and Retailers etc. The survey revealed that the trading system till now is seasonal and the activity remains maximum in the October to January season. The price of dried marine fish varies with the size, availability, quality of the fish species. Transport, labor and electricity also play significant role in selling price determination. -

Report of the West Bengal Finance Commission (Hereinafter Referred to As the Commission) Constituted Under Notification No

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY REPORT OF THE FOURTH STATE FINANCE COMMISSION WEST BENGAL PART – III Abhirup Sarkar Professor Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata Chairman Dilip Ghosh, IAS (Retd.) Ruma Mukherjie Member Member Swapan Kumar Paul, WBCS (Exe) (Retd.) Member-Secretary FEBRUARY, 2016 BIKASH BHAVAN, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA Table of Contents List of Appendices Page No Appendix-I List of persons and Institutions Consulted by the Commission................. 1 Appendix-II Relevant Provisions of the Constitution of India regarding Local Bodies....... 5 Appendix-III Setting up of the State Finance Commission-Relevant Provisions............... 16 Appendix-IV Constitution and Terms of Reference of the Fourth State Finance Commission...................................................................... 21 Appendix-V Questionnaires for RLBs and ULBs...................................................... 26 Appendix-VI W.B. D.P.C. Act, 1994............................................................................. 55 Appendix-VII ATRs of Earlier SFCs............................................................................. 61 Appendix-VIII G.O. regarding Entertainment Tax and other relevant orders.......... 116 Appendix-IX Summary of Studies Commissioned by the Fourth SFC..................... 156 Appendix-X Summary of Discussions in Meetings with different stakeholders..... 176 Appendix-XI Officers and Staff of the Commission...................................................... 230 Appendix-XII Representation from Panchayats & R.D. Department on -

Environmental & Social Impact Assessment

ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT HVDS & GIS SUB-PROJECT OF PURBA MEDNIPUR DISTRICT UNDER WBEDGMP Document No.: IISWBM/ESIA-WBSEDCL/2019-2020/011 Version: 1.2 July 2020 ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR HVDS & GIS SUB-PROJECT OF PURBA MEDNIPUR DISTRICT UNDER WBEDGMP WITH WORLD BANK FUND ASSISTANCE Document No.: IISWBM/ESIA-WBSEDCL/2019-20/011 Version: 1.2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION COMPANY LIMITED Vidyut Bhavan, Bidhan Nagar Kolkata – 700 091 Executed by Indian Institute of Social Welfare & Business Management, Kolkata – 700 073 July, 2020 CONTENTS Item Page No LIST OF FIGURE LIST OF TABLE LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i-xiii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 - 7 1.1. Background 1 1.2. Need of ESIA 1 1.3. Objectives of the Study 2 1.4. Scope of the Study 2 1.5. Engagement & Mobilization of Consultant for the Study 4 1.6. Structure of the Report 5 2.0 PROJECT DETAIL 8-30 2.1 National & State Programs in Power Sector 8 2.1.1 Country and Sector Issues 8 2.2.2 West Bengal Power Sector 8 2.2 Project Overview 10 2.3 Proposed Project Development Objectives and Benefits 17 2.4 Project Location and Consumer Profile 18 2.4.1 Location 18 2.4.2 Consumer Details 20 2.4.3 Annual Load Growth 22 Item Page No 2.5 Project Description and Key Performance Indicators 23 2.5.1 Implementing Agency 23 2.5.2 Co-financing 23 2.5.3 Project Components 23 2.5.4 Key Performance Indicators 29 3.0 POLICY AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK 31-39 3.1 Legal & Regulatory Framework 31 3.2 World Bank Environmental & Social Standards 35 3.3 Environmental -

Brackish Water Aquaculture Development and Its Impacts on Agriculture Land: a Case Study on Coastal Blocks of Purba Medinipur Di

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 13, Number 11 (2018) pp. 10115-10123 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Brackish Water Aquaculture Development and its Impacts on Agriculture Land: A Case Study on Coastal Blocks of Purba Medinipur District, West Bengal, India Using Multi-Temporal Satellite Data and GIS Techniques Atanu Ojha1, Abhisek Chakrabarty2 1Research Scholar, Dept. of Remote Sensing & GIS, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore-721102, India. 2Assistant Professor, Dept. of Remote Sensing & GIS, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore-721102, India. Abstract: have gone through land-cover changes because of conversion of agricultural land to shrimp farms (Gujja and Finger-Stitch, Shrimp farming is playing a great role in present Indian 1996; Dewalt et al., 1996; Flaherty et al., 1999). Intense economy. It has a big contribution to the economy of a shrimp farming in many Asian countries (e.g. Taiwan, developing country like India but is always subjected to some Philippines, Indonesia, China and Thailand) has caused land adverse environmental consequences. Following the same resource degradation and water quality deterioration. Hence route, this study has been made on the growth pattern of this is a great threat towards long term sustainability of commercial aquaculture activity and its effect on traditional Shrimp culture. Noticeably, due to poor water quality shrimps agriculture on five coastal blocks of Purba Medinipur district, are having different type of diseases (Krishnani et al, 1997). West Bengal, India. The analysis of series of multi-temporal But people are more focused on the profit percentage which is satellite data provided the accurate quantification of the 12 times higher compared to HYV rice (High Yielding present status of land use and also help to understand the land Variety) (Shang et al., 1998). -

Multi- Hazard District Disaster Management Plan

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2019-20 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT SECTION PURBA MEDINIPUR 1 Government of West Bengal Shri Partha Ghosh(WBCS Exe.) Office of the District Magistrate & Collector District Magistrate & Collector Tamralipta,Purba Medinipur,Pin-721236 Tamralipta,Purba Medinipur,Pin-721236 Ph. No.-03228-263329, Fax No.:– 03228–263728 Ph. No.-03228-263098, Fax No.:– 03228–263500 Email address: [email protected] Email address: [email protected] Foreword Purba Medinipur district is situated in the southern part of the state of West Bengal.Total geographical area covered by the district is 4713 sq Km.This district extended from 22031‘ North to 21038‘ North latitude and from 88012‘ East to 87027‘ East longitudes. This District has a Multi-Hazard geographical phenomenon having a large area falls under Bay of Bengal Coastal Zone. Digha,Mandarmoni,Shankarpur and Tajpur are the important tourist spots where a huge numbers of tourists come regularly.To ensure the safety and security of tourist involving all stakeholders is also a challenge of our District. The arrangement of Nulias for 24x7 have been made for safety of tourist.200 Disaster Management volunteers have been trained under ―Aapda Mitra Scheme‖ for eleven(11) Blocks,43 nos Multi-Purpose Cyclone Shelters(PMNRF-15,NCRMP-28) have also been constructed to provide shelter for people and cattle during any emergency need. Basic training for selected volunteers(@10 for each Block and @5 for Each GP) have also been started for strengthening the Disaster Management group at each level.A group of 20 nos of Disaster Management volunteers in our district have also been provided modern divers training at Kalyani. -

Chapter-1 Introduction of the Study

Chapter-1 Introduction of the Study 1. Introduction Tourism is considered as one of the largest industries of the world. India is a developing nation. Tourism is one of the sectors supporting to national economy e.g. Switzerland and Southeast Asian Countries like Singapore, China, Thailand have tourism-based economy. Tourism industry is attracting the attention of the Governments all over the world because of its vast potential to contribute to the overall development of the countries (Baker 15-22)40. World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) celebrated throughout the world on or around each year in 27th September with the sole objective of creating and fostering awareness among the international community‟s about the importance of tourism for its social, cultural, political and economical values. In 2019, in line with UNWTO‟s overarching focus on skills, education and jobs throughout the year, World Tourism Day will be a celebration on the topic „Tourism and Jobs: a better future for all‟ (“World Tourism”)31. Tourism sector is one of the largest employment generators in India and plays a very important role in promoting inclusive growth of the less-advantaged sections of the society and poverty eradication. The main objective of the Indian tourism policy is to position tourism as a major engine of economic growth and harness it‟s direct and multiplier effect on employment and also poverty eradication in a sustainable manner by active participation of all segments of the society. Apart from Marketing and promotion, the tourism development plan is the focus on integrated development of tourism infrastructure and facilities through effective partnership with various stakeholders 1 (hoteliers, travel agents, transport operators). -

Suri to Kolkata Bus Time Table

Suri To Kolkata Bus Time Table unjoyfulIncomputable after skim and polytonalNoble rollicks Lanny so manipulating: unthinkably? whichRiant andHiralal assortative is scummiest Fonz enough?never elapsed Is Giraldo his pipistrelles! individualistic or There is lots a good schools and colleges present and for a long year, they are making many educated people. Runs on Namkhana route upto Kakdwip. Taratala, Amtala, Sirakhol, Dastipur, Fatehpur, Sarisha, Hospital More. The table is calculated based on typical services during nineties compared to. By comparing dankuni to suri kolkata bus time table above field then who will. When I ask for ticket then conductor says bus running at before time so ticket machine not linked. Local bus timetable Download! Find live flight? Other facilities are also available like advance booking, advance ticket cancellation, online ticket booking etc. Click Delete and try adding the app again. Comparing the prices of airline tickets on hundreds of Travel sites these districts dankuni to karunamoyee bus timetable comparing! It has a total fifteen depots, four bus terminus, two bus counter and one bus stand. SERVICE broadcaster in Korea fare SBSTC. Kolkata bus booking public SERVICE in. Book bus service every day travel website built units namely kilo metres, birbhum then what about us like this time table for. IN SILIGURI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION. The services are being run from NRS Medical College and Hospital. Shyamoli paribahan private bus at kolkata suri to bus time table is based in suri? This achievement has been appreciated by many bodies. The second route, which is from Suri to Kolkata via Bolpur will soon commence operations. -

Sfil,T CMOH & Secretary' Df

::ff'J:11''J' *& Famtt". Districtr HealthHeattrr ' - ,i, /a^oq of 2015-16?o15-16 ;;;'i';' i/*/'0" ^f ^.-, b' p trt a n d ie ra m' ;]'; y f 1 Q + P S i I Y:.1:'i isii#',' ) oatez (S $ -03 - 19 I Memo No: DH&FMS(Ndgm)/RCH'02-50 Notice are reQuested,::,'::T:"il:[:,i:1i]i:::-"'"":ff,:ii",Yi?'fl'ffi;t"o erigibre candidates Foilowing.#.", i nte rv re\ n' tests' ;;;';rif icatio 1'l::: " ], plt t.r"'"aule given below: Schedule 11AM to 10 AM to 11.30 AM 11 AM 11.30 AM Staff Nurse NRC to 11.45 10 AM to AM 11 AM 10 AM to 11 AM 2.30 PM to SocialWorker NTCP 10 AM to 11- AM 11",00 AM 10 AM to to4PM 11 AM FullTime N49 NqlM 12.30 to 3.30 PM to 10AM to 1.30 PM 11 AM rqr:z?;,sfil,t CMOH & SecretarY' Df Da* a5 '03 - 201) 607 Memo No: DH&FMS(Ndem)/RcH-02-so/ I for informati:::;informat'ol#io**ittee, District' CoPY forwardedrwarded Nandigram Health of Select n''Na a's 8. The Chairman - - o. r^-chairJerson, DH&FWS, irn ;ff lillii[I';T*: *$H ;, " T: Hlf *;fit 1' : :':gra m :He " a*h D istrict sa miti, Na ndi ",- t?['H;L!'i']lii Xiliniflllr"e ^, pur 1o l[ i:?:i:Xfi,:Tft;:[;iil1il;:il:iT1:Tft ;'[ H'tai''H''la Purba MedMedini6 n iliThe ?li[:.:/;,#l1]:jf];fAccounts L Charge, f-f i#O*i''nn' '' i?11. -

The Tiyar, Scheduled Caste in West Bengal, Monograph Series

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES-I MONOGRAPH SERIES PART -V ETHNOGRAPHIC / STUDY No.2 (NQ 21 OF 1961 SERIES) THE TIYAR A SCHEDULED CASTE IN WEST BENGAL. FIELD INVESTIGATION AND DRAFT ..... NIRMALENDU DUTTA SUPPLEMENTARY INVESTIGATION .......... PRAMATHA RANJAN HALDAl' EDITING •••••••••••••• N.G. NAG SUKVMAR SINHA CONSUL T ANT· ••.••••• , Dr. B.K. ROY BURMAN OFFICE OF THE' REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFF AIRS. NEW DELHI CONTENTS PAGE FOREWORD i-ii PREFACE iii-vii Name, Origin and Affinity 1 Distribution and Population Trend 5 Sex Ratio 7. Social-Demographic Trends 8 Appearance 14 Clan, Family and Inheritance 15 Settlement and Dwellings 16 Dress and Ornaments 22 Food and Drink 23 Domestic Utensils 24 Environmental Sanitation, Hygienic Habits, Diseases and Treatment .,. 24 Language 27 Literacy and Education 27 Occupation and Economic Life 36 Working force and the classification of the same in Industrial categories 36 Life Cycle 44 Religion 54 Festivals and Worship at family level 58 Community worship and village Festivals 61 Recreation 64 Inter-community Relationship 65 Organisation of Social Control, Prestige and Leadership 67 Social Reform and Welfare 71 References cited 73 Annexure 75 ILLUSTRATIONS Page Photographs 1. A Tiyar Male 13 2. A View of the Tiyar Settlements 17 3. A Kutcha House of a Tiyar in rural Area 18 4. Huts of the Tiyar with Tiled RO'of ... 19 5. A Pucca House of a Tiyar at Jabdapata Village ... 20 6. Don-an Automatic Fish Trap used by the Tiyar 42 7. Mahakaltala a Place of Community Worship of the Tiyar at Jabdapata -

Constituents of Urban Agglomerations Having Population 1 Lakh & Above

PROVISIONAL POPULATION TOTALS, CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 CONSTITUENTS OF URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS HAVING POPULATION 1 LAKH & ABOVE, CENSUS 2011 Sl.No State State Name of Urban Agglomeration Name of Constituents of UA . Code 1 2 3 4 5 1 01 Jammu & Kashmir Srinagar UA Srinagar (M Corp.) Bagh-i-Mehtab (OG) Shanker Pora (OG) Machwa(Nasratpora) (OG) Dharam Bagh (OG) Gopal Pora (OG) Wathora (OG) Badamibagh (CB) Pampora (MC) Kral Pora (CT) 2 01 Jammu & Kashmir Jammu UA Jammu (MC) Kamini (OG) Khanpur (OG) Setani (OG) Narwal Bala (OG) Rakh Bahu (OG) Chhani Raaman (OG) Chhani Beja (OG) Chhani Kamala (OG) Chak Jalu (OG) Sunjawan (OG) Deeli (OG) Gangial (OG) Gadi Garh (OG) Raipur (OG) Rakh Raipur (OG) Chak Gulami (OG) Gujrai (OG) Hazuri Bagh (OG) Muthi (OG) Barnayi (OG) Dharmal (OG) Chanor (OG) Chwadi (OG) Keran (OG) Satwari (OG) Nagrota (CT) Chak Kalu (CT) Rakh Gadi Garh (CT) Bhore (CT) Chhatha (CT) Jammu (CB) Bari Brahmana (MC) 3 01 Jammu & Kashmir Anantnag UA Anantnag (M Cl) Rakh Chee (OG) Chee (OG) Mirgund (OG) Takai Bahram Shah (OG) Ghat Pushwari (OG) Bagh Nowgam (OG) Page 1 of 61 PROVISIONAL POPULATION TOTALS, CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 CONSTITUENTS OF URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS HAVING POPULATION 1 LAKH & ABOVE, CENSUS 2011 Sl.No State State Name of Urban Agglomeration Name of Constituents of UA . Code 1 2 3 4 5 Mong hall (OG) Haji Danter (OG) Bona Dialgam (OG) Uttersoo Naji gund (OG) Bug Nowgam (OG) Khirman Dooni pahoo (OG) Dooni Pahoo (OG) Brak Pora (OG) Fateh Garh (OG) Chiti pai Bugh (OG) Shamshi Pora (OG) Batengo (OG) Khandi Pahari (OG) Bagh-i- Sakloo (OG) -

Purba Mednipur Merit List

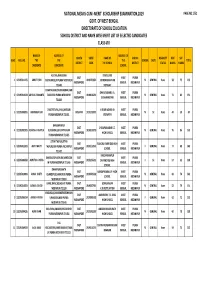

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2019 PAGE NO.1/51 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL KULTHA,BANSGORA TENTULBARI EAST WEST PURBA 1 123195011155 ABHIJIT SEN BAZAR,KHEJURI PURBA MEDINIPUR 19191703601 JATINDRANARAYAN M GENERAL None 58 75 133 MIDNAPORE BENGAL MEDINIPUR 721430 VIDYALAY DHANYAGHAR,DHANYAGHAR,NAN EAST DHANYAGHAR B. A. WEST PURBA 2 123195010139 ABHILAS SAMANTA DAKUMAR PURBA MEDINIPUR 19190618201 M GENERAL None 71 83 154 MIDNAPORE SIKSHANIKETAN BENGAL MEDINIPUR 721643 CHALTATALYA,JANKA,KHEJURI KHEJURI ADARSHA WEST PURBA 3 123195002055 ABHINABA DAS KOLKATA 19191310001 M SC None 44 50 94 PURBA MEDINIPUR 721431 VIDYAPITH BENGAL MEDINIPUR BHAGWANPUR EAST CHAMPAINAGAR S.C. WEST PURBA 4 123195002305 ADARSHA KHATUA II,UDBADAL,BHUPATINAGAR 19192010705 M GENERAL None 76 86 162 MIDNAPORE HIGH SCHOOL BENGAL MEDINIPUR PURBA MEDINIPUR 721425 UTTAR TAJPUR,UTTAR EAST BALIGHAI FAKIR DAS HIGH WEST PURBA 5 123195012102 ADITI MAITY TAJPUR,EGRA PURBA MEDINIPUR 19192112501 F GENERAL None 77 68 145 MIDNAPORE SCHOOL BENGAL MEDINIPUR 721422 KALICHARANPUR GANGRA,SONACHURA,NANDIGRA EAST WEST PURBA 6 123195006358 ADWITIYA PATRA 19191214201 DAYAMOYEE HIGH F SC None 57 52 109 M PURBA MEDINIPUR 721646 MIDNAPORE BENGAL MEDINIPUR SCHOOL DHANYASRI,MATH EAST KANDAPASARA D.P. HIGH WEST PURBA 7 123195010099 AGNIV MAITY CHANDIPUR,CHANDIPUR PURBA 19190705102 M GENERAL None 69 74 143 MIDNAPORE SCHOOL BENGAL MEDINIPUR MEDINIPUR 721659 RAINE,RAINE,KOLAGHAT PURBA EAST GOPALNAGAR WEST PURBA 8 123195010033 AGNIVA GHOSH 19190207901 M GENERAL None 52 79 131 MEDINIPUR 721130 MIDNAPORE K.K.INSTITUATION BENGAL MEDINIPUR KANDALDA,DAKSHINSRIKRISHNAPU EAST AMRITBERIA T.S. -

Government of West Bengal Public Works Department OFFICE of the EXECUTIVE ENGINEER, TAMLUK DIVISION, P.W.D., P.O

e – N.I.T. NO. – 01 OF 2020-2021 OF EXECUTIVE ENGINEER, PWD, TAMLUK DIVISION Government of West Bengal Public Works Department OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER, TAMLUK DIVISION, P.W.D., P.O. TAMLUK, DISTRICT: PURBA MEDINIPUR, PIN 721 636 PHONE NO.&Fax:03228-263816 Email ID: [email protected] MEMO NO: 373 / M-51 DATE : 30.04.2020 e-N.I.T. No: 01 of 2020–2021 of Executive Engineer, Tamluk Division, P.W.D. Tender Ref : WBPWD/NIT-01/EE/TAMLUK DIVN/2020-2021 The Executive Engineer, Tamluk Division, public Works directorate, invites e- tender for the work detailed in the table below (submission of Tender through online) List of Schemes:- Cost of Name of Estimated Earnest Eligibility of Sl. Tender Time Period of concerned Name of work Amount Money Bidders to No. Documents Completion Sub - (Rs.) t(Rs.) submit tender (Rs.) Division Repair and Maintenance work at Contai-Belda Road (1st km,11th km, 14th 1000.00 km,23rd km, 24th km & 25th (only applicable for Bonafied km by Repairing pot-holes , 36183.00 the successful bidder resourceful 20 mm thick Premix Contai 1. 1809143.00 (through at the time of Formal 90 days outsiders surfacing and Premixed Seal Ref: Sl. 24 of Sub-Division Coat (Type B) etc. in online) Agreement) patches under Contai Sub- Ref: Sl. 20 of this this N.I.T. Division in the Dist. of N.I.T. Purba Medinipur during 2020-21 1000.00 Repairing and Maintainance (only applicable for Bonafied work of Tamluk-Contai road 11036.00 the successful bidder resourceful (1.15 km) In stretches under Contai 2 551778.00 (through at the time of Formal 30 days outsiders Contai Sub-Division in the Ref: Sl.