Chapter 6 the Pilgrimage to Jim Morrison 'S Grave at Père Lachaise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13Th FLOOR ELEVATORS

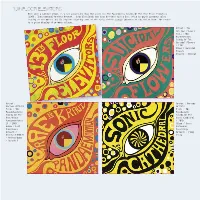

13th FLOOR ELEVATORS With such a seminal album, it’s not surprising that the cover for The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators (1966 : International Artists Artwork : John Cleveland) has been borrowed such a lot, often by psych upstarts (also leaning on the music) and CD compliers wanting some of the early sixties garage ambience to rub off on them. The result is a great display of primary colours. Artist : The Suicidal Flowers Title : The Psychedevilic Sounds Of The Suicidal Flowers / 1997 Album / Suicidal Flowers Artwork : Unknown Artist : Artist : Various Various Artists Artists Title : The Title : The Pseudoteutonic Psychedelic Sounds Of The Sounds Of The Prae-Kraut Sonic Cathedral Pandaemonium # / 2010 14 / 2003 Album / Sonic Album / Lost Cathedral Continence Recordings Artwork / Artwork : Jimmy Reinhard Gehlen Young - Andrea Duwa - Splash 1 COVERED! PAGE 6 1 LEONA ANDERSON ASH RA TEMPEL Leona Anderson’s 1958 long-player Music To Suffer By (Unique Records) This copy of Ash Ra Tempel’s 1973 album is a gem, though I must admit I’ve never been able to get vinyl albums Starring Rosi lovingly recreates Peter to shatter quite like that (or the Buzzcocks TV show intro). The Makers Geitner’s original (cover photo : Claus have actually copied the original image for their EP and then just Kranz). added a new label design. Artist : Magic Aum Gigi Title : Starring Keiko/ 2000? Album / Fractal Records Artwork : Peter Artist : The Geitner (Photo : Makers Magic Aum Gigi) Title : Music To Suffer By / 1995 3 track EP / Estrus Wreckers Artwork : Art Chantry Artist : Smiff-N- Artist : Pavement Wessum Title : Watery, Title : Dah Shinin’ Domestic / 1992 / 1995 EP / Matador Album / Wreck Records Records Artwork : Unknown Artwork : C.M.O.N. -

RELACIONES ENTRE ARTE Y ROCK. APECTOS RELEVANTES DE LA CULTURA ROCK CON INCIDENCIA EN LO VISUAL. De La Psicodelia Al Genoveva Li

RELACIONES ENTRE ARTE Y ROCK. APECTOS RELEVANTES DE LA CULTURA ROCK CON INCIDENCIA EN LO VISUAL. De la Psicodelia al Punk en el contexto anglosajón, 1965-1979 TESIS DOCTORAL Directores: Genoveva Linaza Vivanco Santiago Javier Ortega Mediavilla Doctorando Javier Fernández Páiz (c)2017 JAVIER FERNANDEZ PAIZ Relaciones entre arte y rock. Aspectos relevantes de la cultura rock con incidencia en lo visual. De la Psicodelia al Punk en el contexto anglosajón, 1965 - 1979 INDICE 1- INTRODUCCIÓN 1-1 Motivaciones y experiencia personal previa Pág. 5 1-2 Objetivos Pág. 6 1-3 Contenidos Pág. 8 2- CARACTERÍSTICAS ESTILÍSTICAS, TENDENCIAS Y BANDAS FUNDAMENTALES 2-1 ORÍGENES DEL ROCK 2-1-1 Características fundaMentales del rock priMitivo Pág. 11 2-1-2 La iMagen del rock priMitivo Pág. 15 2-1-2-1 El priMer look del Rock 2-1-2-2 El caudal de iMágenes del priMer Rock y el color 2-1-3 PriMeros iconos del Rock Pág. 17 2-2 BRITISH INVASION Pág. 22 2-3 MODS 2-3-1 Características principales Pág. 26 2-3-2 El carácter visual de la cultura Mod Pág. 29 2-4 PSICODELIA Y HIPPISMO 2-4-1 Características principales Pág. 32 2-4-2 El carácter visual de la Psicodelia y el Arte Psicodélico Pág. 42 2-5 GLAM 2-5-1 Características principales Pág. 55 2-5-2 El carácter visual del GlaM Pág. 59 2-6 ROCK PROGRESIVO 2-6-1 Características principales Pág. 65 2-6-2 El carácter visual del Rock Progresivo Pág. 66 2-7 PUNK 2-7-1Características principales Pág. -

Album Cover Art Price Pages.Key

ART OF THE ALBUM COVER SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC Aretha Franklin, Let Me In Your Life Front Cover, 1974 $1,500 by JOEL BRODSKY (1939-2007) Not including frame Black Sabbath, Never Say Die Album Cover, 1978 NFS by HIPGNOSIS 1968-1983 Blind Faith Album Cover, London, 1969 $17,500 by BOB SEIDEMANN (1941-2017) Not including frame Bob Dylan & Johnny Cash Performance, The Dylan Cash Session Album Cover, 1969 $1,875 by JIM MARSHALL (b.1936 - d.2010) Not including frame Bob Dylan, Blonde on Blonde Album Cover, NYC, 1966 $25,000 by JERRY SCHATZBERG (b.1927) Not including frame Bob Dylan, Greatest Hits Album Cover, Washington DC, 1965 $5,000 by ROWLAND SCHERMAN (b.1937) Not including frame Bob Dylan, Nashville Skyline Album Cover, 1969 $1,700 by ELLIOT LANDY (b.1942) Not including frame Booker T & the MGs, McLemore Ave Front Cover Outtake, 1970 $1,500 by JOEL BRODSKY (1939-2007) Not including frame Bruce Springsteen, As Requested Around the World Album Cover, 1979 $2,500 by JOEL BERNSTEIN (b.1952) Not including frame Bruce Springsteen, Hungry Heart 7in Single Sleeve, 1980 $1,500 by JOEL BERNSTEIN (b.1952) Not including frame Carly Simon, Playing Possum Album Cover, Los Angeles, 1974 $3,500 by NORMAN SEEFF (b.1939) Not including frame Country Joe & The Fish, Fixin’ to Die Back Cover Outtake, 1967 $7,500 by JOEL BRODSKY (1939-2007) Not including frame Cream, Best of Cream Back Cover Outtake, 1967 $6,000 by JIM MARSHALL (b.1936 - d.2010) Not including frame Cream, Best of Cream Back Cover Outtake, 1967 Price on Request by JIM MARSHALL (b.1936 -

Doors La Légende Des Doors Mp3, Flac, Wma

Doors La Légende Des Doors mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: La Légende Des Doors Country: UK & Europe Style: Blues Rock, Psychedelic Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1868 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1940 mb WMA version RAR size: 1609 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 683 Other Formats: ASF VOX MP2 TTA AUD AHX AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Break On Through 1-1 2:25 Written-By – The Doors Light My Fire 1-2 7:05 Written-By – The Doors The Crystal Ship 1-3 2:31 Written-By – Jim Morrison People Are Strange 1-4 2:09 Written-By – The Doors Strange Days 1-5 3:06 Written-By – The Doors Love Me Two Times 1-6 3:13 Written-By – The Doors Alabama Song 1-7 3:16 Written-By – Brecht*, Weill* Five To One 1-8 4:25 Written-By – The Doors Waiting For The Sun 1-9 3:57 Written-By – The Doors Spanish Caravan 1-10 2:57 Written-By – The Doors When The Music's Over 1-11 10:55 Written-By – The Doors Hello, I Love You 2-1 2:14 Written-By – The Doors Roadhouse Blues 2-2 4:02 Written-By – The Doors L.A. Woman 2-3 7:48 Written-By – The Doors Riders On The Storm 2-4 7:14 Written-By – The Doors Touch Me 2-5 3:10 Written-By – The Doors Love Her Madly 2-6 3:17 Written-By – The Doors The Unknown Soldier 2-7 3:22 Written-By – The Doors The End 2-8 11:41 Written-By – The Doors Companies, etc. -

Riders on the Storm

Alina Zamogilnykh, Shutterstock In Venice Beach wordt Jim Morrison nog steeds op handen gedragen American Songbook Riders on the Storm In American Songbook nemen we evergreens, muzikale iconen en songs, Botsende generaties, ze zijn van alle tijden. Nozems, hippies, provo’s, generatie X, Y en Z, die een tijdgeest belichamen onder de loep. He’s hot, he’s sexy and he’s dead; en millennials. De een ziet een orde die moet worden opgeschud, de ander een wereld waarin Rolling Stone Magazine wond er in september 1981 geen doekjes om. vroeger alles beter was. Zo is het anno 2016 en zo was het in 1965, het jaar dat in Los Angeles Te James Douglas (Jim) Morrison was springlevend én al tien jaar morsdood. Doors werd opgericht. In 1965 was het al tien jaar oorlog in Vietnam. De strijd tussen ideolo- Anno nu, 45 jaar nadat de zanger zijn laatste adem uitblies, is de muziek gieën speelde zich niet alleen af op Vietnamese bodem. In het decennium dat de oorlog nog zou van zijn band Te Doors niet vergeten. Is het op zijn laatste rustplaats duren, werd ze in toenemende mate ook in de Verenigde Staten uitgevochten. Muziek was hier- Père Lachaise nooit stil. Zijn people nog steeds strange en bij een belangrijk wapen. Waarmee met scherp werd geschoten toen in 1967 het debuut van Te is Te End altijd nabij… Doors getiteld Te Doors uitkwam. De nummers op het album waren geschreven met een in het TEKST ROBERT DE KONING (JOURNEYLISM.NL) bloed van burgers en soldaten gedoopte pen. 54 WINTER 2016 AmericanS Elektra Records - Joel Brodsky, Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia Joel Brodsky, Wjarek, Shutterstock Jim Morrison met de rest van The Doors: John Densmore, Robby Krieger en Ray Manzarek De laatste rustplaats van Jim Morrison: Père Lachaise in Parijs Apocalypse Now Rutger Hauer on the Storm werd het zaadje waaruit de film Te De climax van de plaat was Te End. -

Universitá Degli Studi Di Milano Facoltà Di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche E Naturali Dipartimento Di Tecnologie Dell'informazione

UNIVERSITÁ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO FACOLTÀ DI SCIENZE MATEMATICHE, FISICHE E NATURALI DIPARTIMENTO DI TECNOLOGIE DELL'INFORMAZIONE SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO IN INFORMATICA Settore disciplinare INF/01 TESI DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA CICLO XXIII SERENDIPITOUS MENTORSHIP IN MUSIC RECOMMENDER SYSTEMS Eugenio Tacchini Relatore: Prof. Ernesto Damiani Direttore della Scuola di Dottorato: Prof. Ernesto Damiani Anno Accademico 2010/2011 II Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the people who helped me during my Ph.D. First of all I would like to thank Prof. Ernesto Damiani, my advisor, not only for his support and the knowledge he imparted to me but also for his capacity of understanding my needs and for having let me follow my passions; thanks also to all the other people of the SESAR Lab, in particular to Paolo Ceravolo and Gabriele Gianini. Thanks to Prof. Domenico Ferrari, who gave me the possibility to work in an inspiring context after my graduation, helping me to understand the direction I had to take. Thanks to Prof. Ken Goldberg for having hosted me in his laboratory, the Berkeley Laboratory for Automation Science and Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, a place where I learnt a lot; thanks also to all the people of the research group and in particular to Dmitry Berenson and Timmy Siauw for the very fruitful discussions about clustering, path searching and other aspects of my work. Thanks to all the people who accepted to review my work: Prof. Richard Chbeir, Prof. Ken Goldberg, Prof. Przemysław Kazienko, Prof. Ronald Maier and Prof. Robert Tolksdorf. Thanks to 7digital, our media partner for the experimental test, and in particular to Filip Denker. -

The Doors Brochure

13589SNAPGALL:Layout 1 6/3/07 07:39 Page 1 Scaling the Lizard King The Doors : Large format photographs from the archives of Joel Brodsky Exhibition runs 21 April to 3 July 2007 13589 06/03/07 Proof 4 13589SNAPGALL:Layout 1 6/3/07 07:39 Page 2 Jim Morrison : The American Poet (extract) Archival pigment print, edition of 3, image size 50 x 50 inches (127cm x 127cm) 13589 06/03/07 Proof 4 135 13589SNAPGALL:Layout 1 6/3/07 07:39 Page 3 Scaling the Lizard King The Doors: Large format photographs from the archives of Joel Brodsky Exhibition runs 21 April to 3 July 2007 In 1967 at his New York studio, Joel Brodsky created what have now become the most recognisable portraits of Jim Morrison - capturing the self styled Lizard King at the peak of his physical and artistic powers. The Doors were poised to release two magnificent albums that year, their self-titled debut, The Doors, and, to many ears, their finest album, Strange Days. ‘Iconic’ is an overused word in the context of celebrity portraiture, but is bang on the money when used to describe Joel’s famous portrait, The American Poet, showing a bare-chested Morrison with arms spread out, staring into the camera. Joel Brodsky’s photographs appeared on the covers of The Doors first two albums, and subsequently on The Soft Parade and many Greatest Hits compilations. 2007 is the Doors' 40th anniversary year, and the surviving members of the band are planning a feast of Doors related activities to celebrate, including a 4 hour international radio special, a feature length documentary for cinema release, previously unissued live recordings, twin volumes of Jim Morrison's poetry, a coffee table photo/scrapbook, and significantly, a major exhibit of memorabilia at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. -

Lesley Ferguson BISIA 450 Midterm Project Proposal – Using Photography Unphotographically

Lesley Ferguson BISIA 450 Midterm Project Proposal – Using Photography Unphotographically I cannot say quite when or how the idea of the “Kodak moment” came about. It was probably a tagline from an advertisement in the Fifties. Regardless of its creation, the concept of this “Kodak moment” has been adapted into our colloquial language, and become synonymous with a perfectly- photographed brief moment in time. In one of these single, flawless images one can see action, time, even emotion. But what of the moments on either side of the one trapped in the photograph? These photos are the ones surrounding that perfect one on the contact sheet, or deleted from the digital slideshow. Why aren’t they considered “Kodak moments”? Sometimes they can provide more insight into the scene that is depicted, and perhaps even more truth. One example that comes to mind is the “Young Lion” series of photographs that Joel Brodsky took of Jim Morrison from the band The Doors. The little known story behind the iconic Christ-pose is that Morrison was completely drunk during the photo shoot, and the drummer of the band, John Densmore, hypothesized that he had to hold his arms out to keep his balance, and the next photo on the contact sheet would show Morrison toppling out of frame. That photo was never printed or seen by anyone but the photographer, but that actually was a more accurate depiction of Morrison than the photos that are still famous today. The goal of my midterm project is to explore the neglected parallel world of the non-Kodak moments. -

Shindig Doors

p001_Shindig_74.qxp 10/11/2017 17:05 Page 1 THE MOODY BLUES THE POPPY FAMILY Back to the future | Out of the darkness OUR BEST OF 2017 THE STRANGE DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN INSIDE THE MAKING OF THEIR LEGENDARY STUDIO ALBUMS WITH PRODUCER BRUCE BOTNICK ALSO! ZOOT MONEY | MORTIMER | FOLK-HORROR ISSUE 74 • £5.50 MAXAYN | THE EASYBEATS | ROBERT WYATT p002_Shindig_74.qxp 10/11/2017 15:22 Page 1 welcome contents Issue 74 December 2017 Howdy Shindiggers, 60 Whilst things in the “Real World” are undoubtedly going from bad to worse, 2017 has been great for Shindig! It really does feel like we have hit our stride and maintained pace. Risky topics now feel less ominous, and quite often pieces on artists Features less associated with what was once viewed as the magazine’s forte have actually gone down best of all. It is, however, no Best Of 2017 surprise to discover readers like all manner of interesting things. Shindig!’s best of the year 21 Taste is always considered. Seeburg 1000 As it’s that feel good time of year I’d like to acknowledge The post war non-selective “industrial jukebox” 28 all who’ve written in, come to our events and tuned into the system minus rock ‘n’ roll radio show. An even bigger thank you goes out to those who buy the magazine on a regular basis. Without you Shindig! Maxayn wouldn’t exist. We appreciate your valued and continued Near forgotten psychedelic funk from the early ‘70s custom. 32 There’s no Xmas silliness in this issue as we’ve done that The Moody Blues quite enough over the past couple of years. -

Om Att Leva I Dödens Närvaro

Om att leva i dödens närvaro Psykolog och doktor Gerald Faris söker tillsammans med sin bror, sociologiprofessor Ralph Faris, att åskådliggöra hur både Janis Joplin och Jim Morrison led av borderlinestörning och hur den till slut kom att tysta deras röster. TEKST Thomas Silfving PUBLISERT 5. august 2012 BRUTALT AVSLÖJANDE: Janis Joplin och Jim Morrison led av borderlinestörning, och efter ett självförbrännande leverne kom den till slut att tysta deras röster. Foto: Joel Brodsky (Jim Morrison) og Keystone Pictures/ZUMA Press (Janis Joplin) Gerald A. och Ralph M. Faris | Living in the Dead Zone: Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison: Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder, Trafford, 1997. 272 sidor När jag för en tid sedan hade en nära relationsupplevelse med min gamla bokhylla, blev jag uppmärksam på en bok jag helt glömt bort att jag ägde. Boktiteln Living in the Dead Zone: Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison – Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder av bröderna Gerald A. och Ralph M. Faris, lät nu som då både aktuell och intressant. Det kanske inte är så konstigt med tanke på att den handlar om gränsproblematik och svårigheten att reglera känslor med därtill hörande skamliga borderlinebeteenden som alkohol- och drogmissbruk, osedliga levnadsvanor och relationskaos. Boken är ett signerat exemplar som jag måste ha inhandlat under en av mina många amerikaresor. Att ibland undersöka vad man har i sin gamla bokhylla kan varmt rekommenderas. En intressant upplevelse som också manar till självreflektion. Vad är det för litteratur man åtnjutit under åren? «När gränserna sedan sprängts och längre inte existerar, gör Jim oss uppmärksamma på att han minsann är «The lizard king. -

The Doors the Doors Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Doors The Doors mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Doors Country: Japan Released: 2005 Style: Psychedelic Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1921 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1563 mb WMA version RAR size: 1103 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 247 Other Formats: MMF XM AHX TTA AU AC3 MPC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Break On Through (To The Other Side) 2:27 2 Soul Kitchen 3:32 3 The Crystal Ship 2:32 4 Twentieth Century Fox 2:32 Alabama Song (Whisky Bar) 5 3:17 Written-By – Bertolt Brecht, Kurt Weill 6 Light My Fire 7:00 Back Door Man 7 3:34 Written-By – Chester Burnett, Willie Dixon 8 I Looked At You 2:22 9 End Of The Night 2:50 10 Take It As It Comes 2:18 11 The End 11:41 Bonus Tracks 12 Moonlight Drive (Version 1) 2:43 13 Moonlight Drive (Version 2) 2:30 14 Indian Summer (8/19/66 Vocal) 2:36 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Rhino Entertainment Company Copyright (c) – Rhino Entertainment Company Manufactured By – Warner Music Australia Distributed By – Warner Music Australia Marketed By – Warner Music Australia Pty. Limited Engineered At – Sunset Sound Recorders Mastered At – Uniteye Published By – Arc Music Published By – Doors Music Co. Published By – Harms Co. Published By – Wixen Music Publishing, Inc. Copyright (c) – Retna Copyright (c) – mptvimages.com Pressed By – SM – 6103101197 Credits A&R [Supervision - Deluxe Edition] – Robin Hurley Art Direction [Deluxe Edition], Design [Package - Deluxe Edition] – Hugh Brown , Jimmy Hole Art Direction, Design – William S. -

Exploring the Funkadelic Aesthetic: Intertextuality and Cosmic Philosophizing in Funkadelic’S Album Covers and Liner Notes

Exploring the Funkadelic Aesthetic 141 Exploring the Funkadelic Aesthetic: Intertextuality and Cosmic Philosophizing in Funkadelic’s Album Covers and Liner Notes Amy Nathan Wright Much has been written about the power of Parliament-Funkadelic’s mu- sic and stage shows,1 two undeniably essential elements of the overall P-Funk package, but far less has been said about the significance of the album covers and liner notes in transmitting the group’s philosophy of the funk,2 an elaborate mythology that helped the band gain worldwide recognition and an almost cult- like following of Funkateers.3 The liner notes and cover art of the Funkadelic albums of the 1970s and early 1980s provide a window into the society and culture of that transformative era and a better understanding of how P-Funk as a collective produced a counterhegemonic aesthetic and philosophy that offered not only biting critiques of politics, society, and the record industry but also space to explore other controversial and complex elements of life, such as sex, religion, emotions, and the meaning of life.4 In particular, I elucidate the influ- ence of one of the most significant P-Funk artists and writers—Pedro Bell—and consider the relationships among writing, visual art, music, and performance as well as the significance of intertextuality5—the way in which P-Funk’s various texts relate or speak to one another to provide greater coherence and mean- ing. The characters who collectively exist as the “Parliafunkadelicment Thang” speak to one another through their music, stage shows, cover artwork, and liner notes, forming interconnected cultural productions in various mediums to pro- duce a coherent worldview.