An Analysis of Selected Programs for the Training of Civil Rights and Community Leaders in the South. By- Horton: Aimee I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

More Than Mrs Robinson: Citizenship Schools in Lowcountry South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia, 1957-1970

More Than Mrs Robinson: Citizenship Schools in Lowcountry South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia, 1957-1970 (A Dissertation submitted in requirement for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy, The University of Nottingham, October 2009) Clare Russell 1 Abstract The first ―citizenship school‖ (a literacy class that taught adults to read and write in order that they could register to vote) was established by Highlander Folk School of Monteagle, Tennessee on Johns Island, South Carolina in 1957. Within three years, the schools were extended across the neighboring Sea Islands, to mainland Charleston and to Savannah, Georgia. In 1961, after Highlander faced legal challenges to its future, it transferred the schools to the fledgling Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), who extended the program across the South. Historians have made far-reaching claims for the successes and benefits of the schools. For example, they claim that they recruited inexperienced but committed people and raised them to the status of community leaders; that they encouraged civic cooperation and political activism and formed the ―foundation on which the civil rights movement‖ was built and they argue that the schools were an unprecedented opportunity for women to develop as activists and as leaders. Yet, they base these claims on certain myths about the schools: that the first teacher Bernice Robinson was an inexperienced and uneducated teacher, that her class was a blueprint for similar ones and that Highlander bequeathed its educational philosophy to the SCLC program. They make claims about female participation without analyzing the gender composition of classes. This dissertation challenges these assumptions by comparing and contrasting programs established in Lowcountry South Carolina and in Savannah. -

Progressive Club

Acknowledgements The Graduate program in Historic Preservation sponsored through Clemson Uni- versity and the College of Charleston would like to extend our thanks to the fol- lowing groups and individuals: The family of Esau Jenkins, The Progressive Club Board members, Wesley United Methodist Church, Craig Bennett with Bennett Preservation Engineering, Historic Charleston Foundation, Clemson University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Professor Amalia Leifeste, teaching assistants Sarah Sanders and Amber Anderson, and the community of John’s Island. Project Completed by: Jane Ashburn, Amanda Brown, Naomi Doddington, John Evangelist, Brent Fortenberry, Jessica Fortney, Haley Schriber, Anna Simpkins, Jean Stoll, Michelle Thompson, Rachel Walling, Meghan White, & Meredith Wilson 1 Introduction The Graduate Program in Historic Preservation with Clemson University/College of Charleston has spent one month researching and documenting the Progressive Club on Johns Island, South Carolina. We spent time researching the history of the Progressive Club so that we had a bet- ter understanding of the structure we would be studying and documenting. Our first day on site, the class divided into small teams, each focusing at a different section of the building and working on measured drawings. All interior and exterior walls have been measured to 1/8 inch per the Historic American Buildings Survey standards. The field drawings and measurements were then entered into AutoCAD software to create digital drawings. See the Progressive Club measured drawings section for the result of this work. Next our class assessed conditions of the Progressive Club. Groups looked at struc- tural concerns where walls are bowing outward, areas with bio growth, areas where chemical alterations have occurred and mechanical failures in the building material. -

GULLAH GEECHEE SUMMER SCHOOL South Carolina, Georgia and Florida — PART I: Origins and Early Development | June 6, 2018 from Pender County, North Carolina, to St

7/8/2018 + The Corridor is a federal National Heritage Area and it was established by Congress to recognize the unique culture of the Gullah Geechee people who have traditionally resided in the coastal areas and the sea islands of North Carolina, GULLAH GEECHEE SUMMER SCHOOL South Carolina, Georgia and Florida — PART I: Origins and Early Development | June 6, 2018 from Pender County, North Carolina, to St. Johns County, Florida. © 2018 Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission Do not reproduce without permission. + + Overview Overview “Gullah” or “Geechee”: Etymologies and Conventions West African Origins of Gullah Geechee Ancestors First Contact: Native Americans, Africans and Europeans Transatlantic Slave Trade through Charleston and Savannah Organization of Spanish Florida + England’s North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia Colonies The Atlantic Rice Coast Charter Generation of Africans in the Low Country Incubation of Gullah Geechee Creole Culture in the Sea Colonies Islands and Coastal Plantations ©Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission | Do not reproduce without permission. ©Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission | Do not reproduce without permission. + + “Gullah” or “Geechee”? “Gullah” or “Geechee”? Scholars are not in agreement as to the origins of the terms “Although Gullah and Geechee — terms whose “Gullah” and “Geechee.” origins have been much debated and may trace to specific African tribes or words — are often Gullah people are historically those located in coastal South used interchangeably these days, Mrs. [Cornelia Carolina and Geechee people are those who live along the Walker] Bailey always stressed that she was Georgia coast and into Florida. Geechee. And, specifically, Saltwater Geechee (as opposed to the Freshwater Geechee, who Geechee people in Georgia refer to themselves as “Freshwater lived 30 miles inland). -

Sep 2 0 2006

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 DORCHESTER ACADEMY BOYS' DORMITORY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Dorchester Academy Boys' Dormitory Other Name/Site Number: Dorchester Center 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 8787 East Oglethorpe Highway (U.S. 84) Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Midway Vicinity: State: GeorgiaCounty: Liberty Code: 179 Zip Code: 31320 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local: _ District: __ Public-State: _ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributin^ 1 _ buildings _ sites _ structures _ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK <m SEP 2 0 2006 by the Secretary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 DORCHESTER ACADEMY BOYS' DORMITORY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

HONORING CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT VETERANS “Write That I” Poems

HONORING CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT VETERANS “Write That I” Poems Poetry by Teachers in the 2018 NEH Summer Institute on the Civil Rights Movement: Grassroots Perspectives Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University, SNCC Legacy Project, and Teaching for Change July, 2018 Table of Contents ABOUT THE COLLECTION........................................................................................................................................ 1 AMELIA BOYNTON ................................................................................................................................................. 2 FOR AMZIE MOORE ............................................................................................................................................... 4 ANNE BRADEN ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ANNIE PEARL AVERY .............................................................................................................................................. 9 BAYARD RUSTIN .................................................................................................................................................. 11 BERNARD LAFAYETTE JR. ..................................................................................................................................... 14 SPROUTING REVOLUTION: BETITA MARTÍNEZ .................................................................................................... -

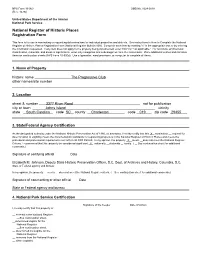

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name The Progressive Club other names/site number 2. Location street & number 3377 River Road not for publication city or town Johns Island vicinity state South Carolina code SC county Charleston code 019 zip code 29455 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant X nationally statewide locally. -

Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship Summer 2018 Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement: Christian Women Leaders’ Contributions to the Paradigm Shift in the Tactics of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Its Affiliates Wook Jong Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Wook Jong. (2018). Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement: Christian Women Leaders’ Contributions to the Paradigm Shift in the Tactics of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Its Affiliates. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 149. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/149. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/149 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grassroots Impacts on the Civil Rights Movement: Christian Women Leaders’ Contributions to the Paradigm Shift in the Tactics of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Its Affiliates By Wook Jong Lee Claremont Graduate University 2018 © Copyright Wook Jong Lee, 2018 All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number:10844448 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10844448 Published by ProQuest LLC ( 2018). -

Juneteenth and the Ongoing African American Freedom Struggle

Juneteenth and the Ongoing African American Freedom Struggle Stacey Close June 19, 2021 Juneteenth Origins On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger of the Union Army announced in Galveston, Texas that slavery was ended, in accordance with the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863. The following year, freed people from Texas spread the idea of celebration with prayers, songs, worship, and dances to celebrate the end of slavery. Dr. Lorenzo Greene, history professor, Lincoln University, born 1899 in Ansonia, CT worked for Dr. Carter G. Woodson at Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History and Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, scholar and NAACP leader Dr. Carter G. Woodson Dr. Lorenzo Greene African American Freedom Struggle Before 1865 (Enslaved people of African ancestry 1797) 19th Century Antebellum South Carolina and Enslaved Family Across Generations Connecticut, African Americans, and Voting • In 1814, William Lanson and Bias Stanley, African Americans in New Haven, protested and argued for “no taxation without representation.” • In 1818, Connecticut’s Constitution restricted suffrage to adult white men, who were age 21 and owned property worth at least seven dollars. • Between 1838 and 1850, African Americans in Connecticut offered to the state legislature 26 sets of papers arguing for the franchise. Rev. James Pennington, Hartford Pastor, and Amos Beman, New Haven Pastor, 1847: Argue for the Right of African Americans to Vote in Connecticut CT 29th Regiment, Civil War Regiment African American Church and Religion Frederick Douglass: The Voice of Lion, 1865 • “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot.” Reconstruction, 1863-68 • Historians of Reconstruction to 1935 and W.E.B. -

Interview, 7-25-11 Page 1 of 66

Dorothy Cotton Interview, 7-25-11 Page 1 of 66 Civil Rights History Project Interview completed by the Southern Oral History Program under contract to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History & Culture and the Library of Congress, 2011 Interviewee: Ms. Dorothy Cotton Interview Date: July 25, 2011 Location: Ithaca, New York Interviewer: Joseph Mosnier, Ph.D. Videographer: John Bishop Length: 2:12:39 Joe Mosnier: You want to stop at any point just say – Dorothy Cotton: Sure. JM: Today is Monday July 25, 2011. My name is Joe Mosnier of the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I’m with our project videographer John Bishop in Ithaca, New York to do an oral history interview for the Civil Rights History Project, which is a joint undertaking of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Library of Congress, and we’re delighted this morning to be with you Ms. Cotton, Ms. Dorothy Cotton, here in Ithaca to, uh, spend some time talking about civil rights history. Dorothy Cotton: Um-hmm, thank you. JM: Let me, um, let me ask a very broad first question for some reflections. I have read where you wrote, that um, you wrote the following, kind of thinking about the 1 Dorothy Cotton Interview, 7-25-11 Page 2 of 66 world that you came up in. You wrote, “From a very early age I had felt like I was in the wrong place.” DC: Yes. Isn’t that interesting? It is to me that, that the sense that I was in the wrong place, um, was very, uh, sort of pervasive in my being. -

FROM: Hi R I AM COHCH .': Ill DATE; '

; i I 1 : . •• M TO - KOURI-S, Of! FROM: Hi R i AM COHCH .': Ill DATE; '. ' • • • - . )':•; ! . COMPAM . I !i; AFRAID YOU ARE ( . TC PU'I ME ON YOUR DART BOARD WHEN YOU HEAR WHAT I HAVE. ! HAVE A COPY OF THE 1962 Ml SS IS D>REC'1 ' ' WE *VE :B 1963's). UH HUH, YES, FT HAS IN ST ALL THE SAME STUFF YOU JUST SENT. i FEEL TERRI8LE THAT YOU WENT TO ALL THAT WORK! EASTLAND'S 0 GOT THE DjM LOR HE. (SMILE) IF WE ARE ONLY ABLE TO USE INFORMATION .., THE RACE OF EMPLOYEES CF EITHER NATIONAL COM AMIES OR LOCAL COMPANIES ON FEDERAL CONTRACT, THIS KSHOULD SAVE YOU SOME WORK. I'LL TRY TO COMPILE A LIST OF THE COMPANIES FOE WHICH WE NEED RACIAL i NFORMATI " ACTUALLY, WE WEILL NEED MORE THAN I FORMATION FOR THESE COMPANIES, WE WILL HEED AN . AGGRIEVED PARTY. (FUN!) 2. UNIONS: i TALKED WITH HERBERT HiLL OF THE NAAC WHEN i WAS IN NEW YORK. HE SAID THE AfL~C!0 CIVIL RIGHTS DEPT. WAS LYING -IN SPITE OF ANY CLAIM?: , THEY MAKE, THEY DO HOT ACT TO AMELIORATE DISCRIMINATION IN THE IR UNIONS. IF THIS IS SO, -, . : , A SURVEY WILL HOT HELP. ANYWAY, HILL FELT A SURVEY WASN'T NECESSARY LEGALISE WITHOUT MARKING ONE WE COULD FA! ELY ACCURATELY STATE THAT 99,A OF THE I LOCALS IN MTSS. ARE EITHER SEGREGATED OK' KXKM EXCLUDE NEGROES ALTOGETHER, WKXX HILL SUGGESTS ICXXTHE FOLLOWING WAYS OF ATTACKING DISCRIMINATION IN UNIONS: A. NON-LEGAL (I.E. NOT REQUIRING A LAWYER OF LAW STUDENT) K1. -

The African American Fight for Equal Education After Jim Crow Luci Vaden University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2014 Before the Corridor of Shame: The African American Fight for Equal Education After Jim Crow Luci Vaden University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Vaden, L.(2014). Before the Corridor of Shame: The African American Fight for Equal Education After Jim Crow. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2747 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Before the Corridor of Shame: The African American Fight for Equal Education After Jim Crow by Luci Vaden Bachelor of Arts University of Tennessee, 2005 Master of Arts University of Tennessee, 2006 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2011 ___________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Patricia Sullivan, Major Professor Kent Germany, Committee Member Lawrence Glickman, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Blair Kelley, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Luci Vaden, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii Abstract “Before the Corridor of Shame: The African American Fight for Equal Education After Jim Crow” analyzes how African American public school students in South Carolina used direct action protest to demand the implementation of quality, desegregated public education in the 1970s. -

Septima P. Clark Papers, Circa 1910 - 1990

Inventory of the Septima P. Clark Papers, circa 1910 - 1990 Avery Research Center College of Charleston 125 Bull Street Charleston, SC 29401 USA http://avery.cofc.edu/archives Phone: (843) 953-7609 | Fax: (843) 953-7607 Table of Contents Descriptive Summary................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical Note...................................................................................................................... 4 Collection Overview...................................................................................................................5 Restrictions................................................................................................................................ 6 Subject Headings...................................................................................................................... 7 Related Material........................................................................................................................ 7 Administrative Information......................................................................................................... 9 Detailed Description of the Collection.....................................................................................10 1. Biographical Papers, 1960-1988 and undated............................................................ 10 2. Works: Writings, Talks, Lectures and Speeches, 1954-1983......................................13 3. Correspondence, 1964-1985......................................................................................