Sheepscot River Watershed Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penobscot Rivershed with Licensed Dischargers and Critical Salmon

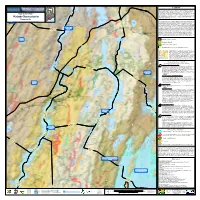

0# North West Branch St John T11 R15 WELS T11 R17 WELS T11 R16 WELS T11 R14 WELS T11 R13 WELS T11 R12 WELS T11 R11 WELS T11 R10 WELS T11 R9 WELS T11 R8 WELS Aroostook River Oxbow Smith Farm DamXW St John River T11 R7 WELS Garfield Plt T11 R4 WELS Chapman Ashland Machias River Stream Carry Brook Chemquasabamticook Stream Squa Pan Stream XW Daaquam River XW Whitney Bk Dam Mars Hill Squa Pan Dam Burntland Stream DamXW Westfield Prestile Stream Presque Isle Stream FRESH WAY, INC Allagash River South Branch Machias River Big Ten Twp T10 R16 WELS T10 R15 WELS T10 R14 WELS T10 R13 WELS T10 R12 WELS T10 R11 WELS T10 R10 WELS T10 R9 WELS T10 R8 WELS 0# MARS HILL UTILITY DISTRICT T10 R3 WELS Water District Resevoir Dam T10 R7 WELS T10 R6 WELS Masardis Squapan Twp XW Mars Hill DamXW Mule Brook Penobscot RiverYosungs Lakeh DamXWed0# Southwest Branch St John Blackwater River West Branch Presque Isle Strea Allagash River North Branch Blackwater River East Branch Presque Isle Strea Blaine Churchill Lake DamXW Southwest Branch St John E Twp XW Robinson Dam Prestile Stream S Otter Brook L Saint Croix Stream Cox Patent E with Licensed Dischargers and W Snare Brook T9 R8 WELS 8 T9 R17 WELS T9 R16 WELS T9 R15 WELS T9 R14 WELS 1 T9 R12 WELS T9 R11 WELS T9 R10 WELS T9 R9 WELS Mooseleuk Stream Oxbow Plt R T9 R13 WELS Houlton Brook T9 R7 WELS Aroostook River T9 R4 WELS T9 R3 WELS 9 Chandler Stream Bridgewater T T9 R5 WELS TD R2 WELS Baker Branch Critical UmScolcus Stream lmon Habitat Overlay South Branch Russell Brook Aikens Brook West Branch Umcolcus Steam LaPomkeag Stream West Branch Umcolcus Stream Tie Camp Brook Soper Brook Beaver Brook Munsungan Stream S L T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp T8 R10 WELS East Branch Howe Brook E Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 WELS Bloody Brook Saint Croix Stream North Branch Meduxnekeag River W 9 Turner Brook Allagash Stream Millinocket Stream T8 R7 WELS T8 R6 WELS T8 R5 WELS Saint Croix Twp T8 R3 WELS 1 Monticello R Desolation Brook 8 St Francis Brook TC R2 WELS MONTICELLO HOUSING CORP. -

Lady Crabs, Ovalipes Ocellatus, in the Gulf of Maine

18_04049_CRABnotes.qxd 6/5/07 8:16 PM Page 106 Notes Lady Crabs, Ovalipes ocellatus, in the Gulf of Maine J. C. A. BURCHSTED1 and FRED BURCHSTED2 1 Department of Biology, Salem State College, Salem, Massachusetts 01970 USA 2 Research Services, Widener Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA Burchsted, J. C. A., and Fred Burchsted. 2006. Lady Crabs, Ovalipes ocellatus, in the Gulf of Maine. Canadian Field-Naturalist 120(1): 106-108. The Lady Crab (Ovalipes ocellatus), mainly found south of Cape Cod and in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence, is reported from an ocean beach on the north shore of Massachusetts Bay (42°28'60"N, 70°46'20"W) in the Gulf of Maine. All previ- ously known Gulf of Maine populations north of Cape Cod Bay are estuarine and thought to be relicts of a continuous range during the Hypsithermal. The population reported here is likely a recent local habitat expansion. Key Words: Lady Crab, Ovalipes ocellatus, Gulf of Maine, distribution. The Lady Crab (Ovalipes ocellatus) is a common flats (Larsen and Doggett 1991). Lady Crabs were member of the sand beach fauna south of Cape Cod. not found in intensive local studies of western Cape Like many other members of the Virginian faunal Cod Bay (Davis and McGrath 1984) or Ipswich Bay province (between Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras), it (Dexter 1944). has a disjunct population in the southern Gulf of St. Berrick (1986) reports Lady Crabs as common on Lawrence (Ganong 1890). The Lady Crab is of consid- Cape Cod Bay sand flats (which commonly reach 20°C erable ecological importance as a consumer of mac- in summer). -

Narraguagus River Water Quality Monitoring Plan

Narraguagus River Water Quality Monitoring Plan A Guide for Coordinated Water Quality Monitoring Efforts in an Atlantic Salmon Watershed in Maine By Barbara S. Arter BSA Environmental Consulting And Barbara Snapp, Ph. D. January 2006 Sponsored By The Narraguagus River Watershed Council Funded By The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Narraguagus River Water Quality Monitoring Plan A Guide for Coordinated Water Quality Monitoring Efforts in an Atlantic Salmon Watershed in Maine By Barbara S. Arter BSA Environmental Consulting And Barbara Snapp, Ph. D. January 2006 Sponsored By The Narraguagus River Watershed Council Funded By The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Narraguagus River Water Quality Monitoring Plan Preface In an effort to enhance water quality monitoring (WQM) coordination among agencies and conservation organizations, the Project SHARE Research and Management Committee initiated a program whereby river-specific WQM Plans are developed for Maine rivers that currently contain Atlantic salmon populations listed in the Endangered Species Act. The Sheepscot River WQM Plan was the first plan to be developed under this initiative. It was developed between May 2003 and June 2004. The Action Items were finalized and the document signed in March 2005 (Arter, 2005). The Narraguagus River WQM Plan is the second such plan and was produced by a workgroup comprised of representatives from both state and federal government agencies and several conservation organizations (see Acknowledgments). The purpose of this plan is to characterize current WQM activities, describe current water quality trends, identify the role of each monitoring agency, and make recommendations for future monitoring. The project was funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. -

1.NO-ATL Cover

EXHIBIT 20 (AR L.29) NOAA's Estuarine Eutrophication Survey Volume 3: North Atlantic Region July 1997 Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce EXHIBIT 20 (AR L.29) The National Estuarine Inventory The National Estuarine Inventory (NEI) represents a series of activities conducted since the early 1980s by NOAA’s Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) to define the nation’s estuarine resource base and develop a national assessment capability. Over 120 estuaries are included (Appendix 3), representing over 90 percent of the estuarine surface water and freshwater inflow to the coastal regions of the contiguous United States. Each estuary is defined spatially by an estuarine drainage area (EDA)—the land and water area of a watershed that directly affects the estuary. The EDAs provide a framework for organizing information and for conducting analyses between and among systems. To date, ORCA has compiled a broad base of descriptive and analytical information for the NEI. Descriptive topics include physical and hydrologic characteristics, distribution and abundance of selected fishes and inver- tebrates, trends in human population, building permits, coastal recreation, coastal wetlands, classified shellfish growing waters, organic and inorganic pollutants in fish tissues and sediments, point and nonpoint pollution for selected parameters, and pesticide use. Analytical topics include relative susceptibility to nutrient discharges, structure and variability of salinity, habitat suitability modeling, and socioeconomic assessments. For a list of publications or more information about the NEI, contact C. John Klein, Chief, Physical Environ- ments Characterization Branch, at the address below. -

A History of Oysters in Maine (1600S-1970S) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Darling Marine Center Historical Documents Darling Marine Center Historical Collections 3-2019 A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Lackovic, Randy, "A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s)" (2019). Darling Marine Center Historical Documents. 22. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents/22 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Darling Marine Center Historical Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) This is a history of oyster abundance in Maine, and the subsequent decline of oyster abundance. It is a history of oystering, oyster fisheries, and oyster commerce in Maine. It is a history of the transplanting of oysters to Maine, and experiments with oysters in Maine, and of oyster culture in Maine. This history takes place from the 1600s to the 1970s. 17th Century {}{}{}{} In early days, oysters were to be found in lavish abundance along all the Atlantic coast, though Ingersoll says it was at least a small number of oysters on the Gulf of Maine coast.86, 87 Champlain wrote that in 1604, "All the harbors, bays, and coasts from Chouacoet (Saco) are filled with every variety of fish. -

2021 Striped Bass Regulations

2021 MAINE STRIPED BASS REGULATIONS If you are a recreational saltwater fisherman, Maine law may require you to register with the Maine Saltwater Recreational Fishing Registry. To learn more or to register visit: www.maine.gov/saltwater or call 207-633-9500. The following Maine saltwater recreational fishing regulations are current as of June 8, 2021. However, they are subject to change. Please contact our office or your local Marine Patrol Officer with questions. All minimum lengths are total length, NOT fork length. The sale of fish by recreational anglers is prohibited. Maine’s striped bass regulations cover all Maine coastal waters up to the head of tide in all rivers. In addition, there are special regulations in effect from December 1 through June 30 in the Kennebec, Sheepscot and Androscoggin Rivers and all related tributaries (see “SPECIAL KENNEBEC REGULATIONS” below). FEDERAL REGULATION It is unlawful to fish for, take or possess striped bass in Federal waters (waters greater than 3 miles from shore). STATEWIDE REGULATIONS OPEN SEASON January 1 through December 31, inclusive (except the Kennebec watershed, see below). BAG LIMITS A person may take and possess 1 fish per day. SIZE LIMITS The fish must be equal to or greater than 28 inches and less than 35 inches total length. “TOTAL LENGTH” is a straight line measurement from the lower jaw to the tip of the tail with the tail pinched together. DISPOSITION Personal use only, sale is prohibited. Fish must remain whole and intact. GENERAL GEAR RESTRICTIONS • Hook and line only, no gaffing of striped bass. • No bait allowed when using treble hooks. -

Dynamics of Larval Fish Abundance in Penobscot Bay, Maine

81 Abstract–Biweekly ichthyoplankton Dynamics of larval fi sh abundance surveys were conducted in Penobscot Bay, Maine, during the spring and early in Penobscot Bay, Maine summer of 1997 and 1998. Larvae from demersal eggs dominated the catch from late winter through spring, but Mark A. Lazzari not in early summer collections. Larval Maine Department of Marine Resources fi sh assemblages varied with tempera- P.O. Box 8 ture, and to a lesser extent, plankton West Boothbay Harbor, Maine 04575 volume, and salinity, among months. E-mail address: [email protected] Temporal patterns of larval fi sh abun- dance corresponded with seasonality of reproduction. Larvae of taxa that spawn from late winter through early spring, such as sculpins (Myoxocepha- lus spp.), sand lance (Ammodytes sp.), and rock gunnel (Pholis gunnellus) For most fi sh, the greatest mortality tial variation in species diver sity and were dominant in Penobscot Bay in occurs during early life stages (Hjort, abundance, and 3) to relate these vari- March and April. Larvae of spring to early summer spawners such as 1914; Cushing, 1975; Leggett and Deb- ations to differences in location and en- winter fl ounder (Pleuronectes america- lois, 1994). Therefore, it is essential that vironmental variables. nus) Atlantic seasnail (Liparis atlan- fi sh eggs and larvae develop in favorable ticus), and radiated shanny (Ulvaria habitats that maximize the probability subbifurcata) were more abundant in of survival. Bigelow (1926) recognized Materials and methods May and June. Penobscot Bay appears the signifi cance of the coastal shelf for to be a nursery for many fi shes; there- the production of fi sh larvae within the Field methods fore any degradation of water quality Gulf of Maine, noting that most larvae during the vernal period would have were found within the 200-m contour. -

Atlantic Salmon Commission Public Advisory Panel

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary . 2 Introduction . ... 3 Atlantic Salmon Commission Offices and Staff................................ 4 Funding.............................................................................. 5 Stocking .............................................................................. 6 Research and Management..................................................... 9 Water Quality Monitoring ......................................................... 12 Individual River Reports Aroostook River ............................................................. 19 Cove Brook .................................................................. 22 Dennys River.................... 24 Ducktrap River. .............................................................. 29 East Machias River ............................................................................ 31 Kenduskeag Stream ........................................................................... 33 Kennebec River .................................................................................. 35 Machias River .................................................................................... 37 Narraguagus River ............................................................................ -

Wright Pierce

SUBMISSION 05-03-16 CONFIDENTIAL KENNEBUNK LIGHT AND POWER DISTRICT HYDROPOWER FACILITY ALTERNATIVES ASSESSMENT STUDY MA9 2016 SUBMISSION 05-03-16 KENNEBUNK LIGHT AND POWER DISTRICT HYDROPOWER FACILITY ALTERNATIVES ASSESSMENT STUDY KENNEBUNK, MAINE TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION DESCRIPTION PAGE 1 SUMMARY OF ALTERNATIVES 1.1 Prequel ..................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Summary of Alternatives .......................................................... 1-3 1.3 Alternative #1 – Seek New License to Continue Operations ................................................................. 1-3 1.4 Alternative #2 – Seek License Exemption to Continue Operation ................................................................... 1-4 1.5 Alternative #3 – Seek FERC Non-jurisdiction Only for the Kesslen Site ................................................................... 1-5 1.6 Alternative #4 – Cease Operation and Surrender the FERC License for All Three Sites ............................................ 1-5 2 ASSESSMENT OF ALTERNATIVE #1 2.1 Alternative Description ............................................................ 2-1 2.2 Environmental Implications of this Alternative ....................... 2-2 2.3 Secondary Economic Implications of this Alternative ............ 2-7 2.4 Benefits of the Alternative ....................................................... 2-8 2.5 Impacts and Challenges of the Alternative .............................. 2-9 2.6 Cost Assessment of the Alternative ......................................... -

Shells of Maine: a Catalogue of the Land, Fresh-Water and Marine Mollusca of Maine

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1908 Shells of Maine: a Catalogue of the Land, Fresh-water and Marine Mollusca of Maine Norman Wallace Lermond Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pamp 353 c. 2 Vickery SHELLS OF MAINE Norman Wallace Lermond Thomaston SHELLS OF MAINE. A Catalogue of the Land, Fresh-water and Marine Mollusca of Maine, by Norman Wallace Lermond. INTRODUCTORY. No general list of Maine shells—including land, fresh-water and marine species—-has been published since 1843, when Dr. J. W. Mighels’ list was printed in the Boston Journal of Natural History. Dr. Mighels may be called the “Pioneer” conchologist of Maine. By profession a physician, in his leisure hours he was a most enthusiastic collector and student of all forms of molluscan life. Enthusiasm such as his was “contagious” and he soon had gathered about him a little band of active students and collectors. Of these Capt. Walden of the U. S. Revenue Cutter “Morris” was dredging in deep water and exploring the eastern shores and among the islands, and “by his zeal procured many rare species;” Dr. -

Wetlands Characterization

k o o r B w o d a e M An Approach to Conserving Maine's Natural r e LEGEND Space for Plants, Animals, and People e D D This map depicts all wetlands shown on National Wetland Inventory (NWI) maps, but e www..begiinniingwr iitthhabiittatt..org e categorized them based on a subset of wetland functions. This map and its depiction J p E e v F i F C of wetland features neither substitute for nor eliminate the need to perform on-the- E R B A R o ground wetland delineation and functional assessment. In no way shall use of this map L S v e O SNupplementary Map 7 e n A N r e diminish or alter the regulatory protection that all wetlands are accorded under y B D applicable State and Federal laws. For more information about wetlands characterization, r contact Elizabeth Hertz at the Maine Department of Conservation (207-287-8061, o Wetlands Cha racterization ok Wetlands Characterization [email protected]). 32 Damariscotta Damariscotta )" 215 W )" Lake N Sheepscot River A This map is non-regulatory and is intended for planning purposes only O The Wetlands Characterization model is a planning tool intended to help identify likely L 213 B Kalers Drainage )" D wetland functions associated with significant wetland resources and adjacent uplands. L O Pond E Using GIS analysis, this map provides basic information regarding what ecological B B O O services various wetlands are likely to provide. These ecological services, each of which R R O has associated economic benefits, include: floodflow control, sediment retention, finfish O habitat, and/or shellfish habitat. -

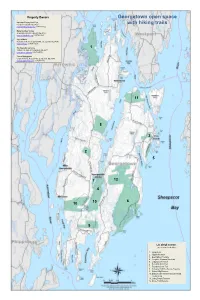

Georgetown Open Space with Hiking Trails

Property Owners Georgetown open space Kennebec Estuary Land Trust P.O. Box 1128, Bath, ME 04530 with hiking trails www.kennebecestuary.org (207-442-8400) Maine Audubon Society 20 Gisland Farm Rd., Falmouth, ME 04105 www.maineaudubon.org (207-781-2330) State of Maine Reid State Park, 375 Seguinland Rd., Georgetown, ME 04548 www.maine.gov (207-371-2303) The Nature Conservancy 1 14 Maine St., Suite 401, Brunswick, ME 04011 www.nature.org/maine (888-729-5181) Town of Georgetown 50 Bay Point Rd., P.O. Box 436, Georgetown, ME 04548 www.georgetownme.com (207-371-2820) 11 8 3 2 5 7 12 4 10 6 10 9 List of trail reserves (see reverse for details) 1. Flying Point 2. Higgins Mountain 3. Ipcar Natural Preserve 4. Josephine Newman Sanctuary 5. Ledgewood Preserve 6. Reid State Park Trail 7. Round the Cove Trail 8. Schoener Robinhood Cove Preserve 9. Weber Kelly Preserve 10. Berry Woods Preserve and James and Lavina Kemp 11. Loring Conant Preserve 12. Morse Pond Preserve Trail Descriptions 4 JOSEPHINE NEWMAN SANCTUARY 7 ROUND THE COVE TRAIL Trail Length: 2.6 miles, 3 trails, easy to moderate Trail Length: 1.4 miles, easy to moderate Owner: Town of Georgetown FLYING POINT Owner: Maine Audubon Society 1 Directions: From Route 127 in Georgetown Center turn right at the Directions: From Route 127 take Bay Point Road. Park at the Trail Length: 0.8 miles, moderate with hills sign for the sanctuary, shortly after crossing the first bridge on Georgetown Historical Society building on the left. The trail begins Owner: The Nature Conservancy Robinhood Cove.