Co-Movement of Residential Real Estates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of buildings with confirmed / probable cases of COVID-19 List of residential buildings in which confirmed / probable cases have resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date) District Building name Related confirmed / probable case number Sai Kung Yee Ching House Yee Ming Estate 58,128 Wan Chai Envoy Garden 114, 213 Case notified by the health Southern Block 28, Baguio Villa authority of Canada and Case 117, 118 Tai Po Heng Tai House, Fu Heng Estate 119, 124, 140 Tuen Mun On Hei House, Siu Hei Court 120, 121 Sha Tin Mau Lam House, Kwong Lam Court 122 Tsuen Wan Tower 7, Bellagio 123, 129 Kwun Tong Block T, Telford Gardens 125 Kwun Tong Block 26, Phase 2, Laguna City 126, 127 130, 131,133, Kwai Tsing iPlace 138 Central & Western Serene Court, 35 Sai Ning Street 132 Tai Po Ng Tung Chai, Lam Tsuen 134 Central & Western View Villa 135 Southern 18 Stanley Main Street 136 Wan Chai Block A, Tai Hang Terrace 137 Eastern Cornell Centre 139 Sai Kung 684 Clear Water Bay Road 141 Kwai Tsing Tivoli Garden 142 North Lai Ming House, Wah Ming Estate 143 Sai Kung The Palisades 145 Eastern Fort Mansion 146 Central & Western Kellett View Town Houses, 65 Mount 147, 148 District Building name Related confirmed / probable case number Kellett Road Southern Wah Cheong House, Wah Fu 2 Estate 149 Yau Tsim Mong Hotel ICON 150 Yau Tsim Mong Block A, Chungking Mansions 151 Tuen Mun Tower 1, Oceania Heights 152 Shatin Block 10, Pristine Villa 153 Kowloon City 8 Hok Ling Street 154 Wong Tai Sin Lung Chu House, Lung Poon -

Hong Kong Gold Coast

Residents’ Clubhouse Facilities Residences Leasing Enquiries ⡞㹐剚䨾鏤倷Q BBQ Stove & Pool Side BBQ ⡞㸕獆叆鑉T: 8108 0200 Q Billiard 敯掑旰⿻剚䨾寒歿敯掑㛄 Hong Kong Gold Coast Map Q Function呲椕㹔 Room & Indoor Multi Function Room Q Gymnasium 眏湡㹔⿻竸ざ崞⹛㹔 Q Mahjong Room⨴魨㹔 Q Indoor and Outdoor란ꦿ㹔 Swimming Pool Hong Kong Gold Coast Residences (Phase 2) Q Kid’s Cove 㹔Ⰹ⿻㹔㢫岷寒 Q Laundry Room⯥留坿㕨 Q Music Room 荈⸔峤邆䨼 껻度랔ꆄ嵳䁘⡞㸕 ✳劍 갉坿㹔 )LUVW)ORRU/HYHOb Q Sauna Room and Steam Room 껻度랔ꆄ嵳䁘㖒㕬 ♧垜 Q Squash Court 呺䭭㹔⿻襓孵嵮㹔 Tai Pan 㠗椕㜥 ˙ Ballroom 㣐棵䑼 Q Table Tennis Room ˙ 㹶剚䑼 Q Tennis Court ⛝⛟椕㹔 Q The Patio 笪椕㜥 笃蘟䏭㕨 Lobby Level Voyager’s剚䨾㣐㛔 ˙ 黜菕䑼 *URXQG/HYHOb Q 0DF/HKRVH7UDLOb The Commander’s㖒♴ Deck ˙ ♳㼟ゅ Gold Coast Eco Farm Q 7DL/DP&KXQJ5HVHUYRLUbb 7KRXVDQG,VODQG/DNH b띋椚嵞䖜 Residents’ Clubhouse 랔ꆄ嵳䁘笃䝑鴍蛅 Fruit Garden ⡞㹐剚䨾 㣐奭嶑宐㝦 ⼪䃋廪 ⼪卓㕨 Gold Coast Fun Farm Country Club House 랔ꆄ嵳䁘䗱鴍蛅 Foot Bridge Swing Garden Gold Coast Lawn ꀀ勠⥡坿鿈 遤➃堀 ꮸꭻⰗ㕨 랔ꆄ虋㗣 Hong Kong Gold Coast Marina Villas Front Lawn /HDVLQJ2ʡFH 嵳抓ⴽ㞱 Harrow International School Hong Kong 笃虋㕨 껻度랔ꆄ嵳䁘獆贖 Gold Coast Yacht and Country Club Marina Club House ㆁ繏껻度㕜ꥹ㷸吥 랔ꆄ嵳䁘ꀀ勠⥡坿鿈v麉萜剚 Music Wall 麉萜剚 Jogging Trail 箣駵䖜 ✽⹛갉坿 Angel’s Wings The Deck 㣔⢪⛓缾 Gold Coast Piazza 랔ꆄ嵳䁘㉂㜥 Hong Kong Gold Coast Customer Service Centre Marina 껻度랔ꆄ嵳䁘 嵳抓 㹐䨩剪⚥䗱 Leaf Path Hong Kong Gold Coast Residences (Phase 1) 涰衞䖜 껻度랔ꆄ嵳䁘⡞㸕 ♧劍 Outdoor Kids Island Kids 荛 麉坿㕨 Castle Peakꫭ㿋Ⱇ騟 Road Mini Train Ride ⯥留㼭抡鮦 The Lawn The Lookout Dolphin Square Hong Kong Gold Coast Hotel Grand Ballroom 嵳韂䑞㜥 Gold Coast Farm 껻度랔ꆄ嵳䁘ꂋ䏅 Pools and Waterslides 㹶剚䑼 랔ꆄ嵳䁘鴍蛅 康岷寒⿻徿宐唑 Gold Coast Nature Path The Chapel and Terrace 랔ꆄ嵳䁘荈搭䖜 㭶狲狲㛔⿻䝑搭䏭㕨 Gold Coast Satay Inn Lobby Level Ropes Course 尪㍪鮯 㖒♴㣐㛔 Entrance 랔ꆄ嵳䁘넞瑠粫笪 Ⰵ〡 Water Park “Sharks and Pirates” Gold Coast Adventure Zone 랔ꆄ宐⹛坿㕨 Lobby Lounge Prime Rib 㣐㛔ꂋゅ 嵳䁘䩦䨼 닔눴ⱎꦖ䃋 Lower Ground YUÈ Sand Pit Level 礡 Gold Coast Square ⡜㾵㖒♴ 䨡尪寒 㢵欽鸁㜥㖒 Gold Coast Ziplines Golden Beach Cafe 랔ꆄ嵳䁘굳㣔ꏈ程 Lagoon Access to Beach 랔ꆄ岷抂 翕庍ㄳ㉱䑼 鸒䖃尪抂涸ⴀⰅ〡 %XWWHUʜLHVDQG+HUEV)DUP 軨莻껻虋鴍蛅 The map is not drawn to scale 姽㖒㕬⚛ꬌ䭾撑嫲⢿粭殥. -

Participating Buildings in Tuen Mun District 屯門區的參與屋苑

Tuen Mun (屯門) Estates (屋苑) Estate/Building 屋苑/大廈 2GETHER 䨇寓 Aegean Coast 愛琴海岸 Affluence Garden 澤豐花園 Alpine Garden 冠峰園 Aqua Blue 浪濤灣 Aquamairne Garden 海慧花園 Avignon 星堤 Beaulieu Peninsula 蟠龍半島 Beneville 聚康山莊 Blossom Garden 寶怡花園 Botania Villa 綠怡居 Brilliant Garden 彩暉花園 Butterfly Estate 蝴蝶邨 Castle Peak Government Quarters 青山政府宿舍 Chelsea Heights 卓爾居 Dragon Inn Court 容龍居 Eight Regency 珀御 Eldo Court 雅都花園 Elegance Gardens 怡樂花園 Fu Tai Estate 富泰邨 Glorious Garden 富健花園 Goodrich Garden 盈豐園 Goodview Garden 豐景園 Greenland Garden 翠林花園 Handsome Court 恆順園 Hanford Garden 恆福花園 Estate/Building 屋苑/大廈 Harvest Garden 恒豐園 Hong King Garden (Tuen Mun) 屯門康景花園 Hong Kong Gold Coast 香港黃金海岸 Jade Grove 琨崙 Jade View Villa 翠景花園 Kin Sang Estate 建生邨 Kingston Terrace 景新臺 Leung King Estate 良景邨 Lung Yat Estate 龍逸邨 Marina Garden 慧豐園 Miami Beach Towers 邁亞美海灣 Nerine Cove 南浪海灣 Noble Place 景峰豪庭 On Ting Estate 安定邨 ORI 豐連 Palatial Coast - Grand Pacific Views / Grand Pacific Heights 帝濤灣-浪琴軒/海琴軒 Palm Cove 翠濤居 Parkland Villas 叠茵庭 Peridot Court 瑜翠園 Po Tin Estate 寶田邨 Prime View Garden 景峰花園 Sam Shing Estate 三聖邨 Seaview Garden 海景花園 Siu Hei Court 兆禧苑 Siu Hin Court 兆軒苑 Siu Hong Court (Phase 3 & 4) 兆康苑(第三、四期) Siu Kwai Court 兆畦苑 Siu Lun Court 兆麟苑 South Crest 南岸 Estate/Building 屋苑/大廈 South Hillcrest 倚嶺南庭 Sun Tuen Mun Centre 新屯門中心 Tai Hing Estate 大興邨 Tai Hing Garden (Phase II) 大興花園(第二期) The SeaCrest 嘉悅半島 The Sherwood 豫豐花園 Tsing Chung Koon Road Government Quarters 青松觀道政府宿舍 Tsing Yung Terrace 青榕臺 Tsui Ning Garden 翠寧花園 Tuen Fu Road Disciplined Services Quarters 屯富路紀律部隊宿舍 Tuen Mun Town Plaza 屯門市廣場 Tuen -

香港物業管理公司協會有限公司the Hong Kong Association of Property Management Companies Limited

香港物業管理公司協會有限公司 The Hong Kong Association of Property Management Companies Limited 會員轄下物業資料 Date : 01-03-2020 Members Portfolios Property Registers 會員編號 F-0045/96 公司名稱: 信和物業管理有限公司 Membership No.: Company Name: Sino Estates Management Ltd 總樓宇面積 單位面積 (平方呎) 類別 物業名稱及地點 物業地址 類別/座數 單位數目 Unit Size GFA 樓齡 管理年數 Type Properties Properties Address Type/No. of Blocks No. of Units Min/Max Sq. Ft. Age Yrs.Managed C 148 Electric Road C Argyle Centre Phase I C Cameron Plaza C China Hong Kong City C China Hong Kong Tower C Consumer Council Resource Centre Bldg C Empire Centre C Exchange Tower C Far East Finance Centre C Futura Plaza C Ginza Square C Golden Centre C Hollywood Centre C Hong Kong Pacific Centre C Kwun Tong Harbour Plaza C Kwun Tong Plaza C Lee Tung Avenue C Marina House C Maritime Bay - Shopping Mall C New York House 香港物業管理公司協會有限公司 The Hong Kong Association of Property Management Companies Limited 會員轄下物業資料 Date : 01-03-2020 Members Portfolios Property Registers 會員編號 F-0045/96 公司名稱: 信和物業管理有限公司 Membership No.: Company Name: Sino Estates Management Ltd 總樓宇面積 單位面積 (平方呎) 類別 物業名稱及地點 物業地址 類別/座數 單位數目 Unit Size GFA 樓齡 管理年數 Type Properties Properties Address Type/No. of Blocks No. of Units Min/Max Sq. Ft. Age Yrs.Managed C Ocean Building C Omega Plaza C One Capital Place C Pacific Plaza C Pan Asia Centre C Ritz Plaza C Shatin Galleria C Sino Plaza C Skyline Tower C The Centrium C The Hennessy C Tsim Sha Tsui Centre C Tuen Mun Town Plaza Phase II (Carpark) C Winfield Comm. -

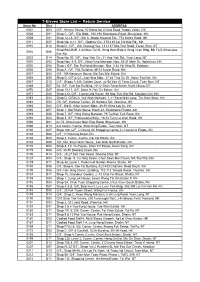

7-Eleven Store List – Return Service Store No

7-Eleven Store List – Return Service Store No. Dist ADDRESS 0001 D03 G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0008 D01 Shop C, G/F., Elle Bldg., 192-198 Shaukiwan Road, Shaukiwan, HK 0009 D01 Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0011 D07 Shop No. 6-11, G/F., Godfrey Ctr., 175-185 Lai Chi Kok Rd., Kln 0015 D12 Shop D., G/F., Win Cheung Hse, 131-137 Sha Tsui Road, Tsuen Wan, NT Shop B2A,B2B, 2-32 Man Tai St, Wing Wah Bldg & Wing Yuen Bldg, Blk F&G,Whampoa 0016 D06 Est, Kln 0022 D14 Shop No. 57, G/F., Hop Yick Ctr., 31 Hop Yick Rd., Yuen Long, NT 0030 D02 Shop Nos. 6-9, G/F., Ning Fung Mansion, Nos. 25-31 Main St., Apleichau, HK 0035 D04 Shop J G/F, San Po Kong Mansion, Nos. 2-32 Yin Hing St, Kowloon 0036 D06 Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0037 D04 G/F, 109 Geranum House, Ma Tau Wai Estate, Kln 0058 D05 Shop D, G/F & C/L, Lap Hing Bldg., 37-43 Ting On St., Ngau Tau Kok, Kln 0067 D13 G/F., Shops A & B, Golden Court, 42-58 Yan Oi Tong Circuit, Tuen Mun, NT 0069 D07 B2, G/F, Yuet Bor Building, 10-12 Shun Fong Street, Kwai Chung, NT 0070 D07 Shop 15-17, G/F, Block 9, Pak Tin Estate, Kln 0077 D08 Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0083 D04 Shop D, G/F&C/L Yuk Wah Mansion, 1-11 Fong Wah Lane, Tsz Wan Shan, Kln 0084 D03 G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 D02 G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0086 D07 Shop 1, Mei Shan House, Block 42, Shekkipmei Estate, Kln 0093 D08 Shop 7, G/F, Hing Wong Mansion, 79 Tai Kok Tsui Road, Kln 0094 D03 Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0096 D01 62-74, Shaukiwan Main East Road, Shaukiwan, HK 0098 D13 8-9 Comm. -

Corporate 1 Template

Vigers Hong Kong Property Index Series • As a complement to the existing property information related to the Hong Kong property market • To better inform public of the ever-changing residential market as Vigers has selected residential districts or areas which will be impacted by the Objectives territories’ infrastructure project, i.e. the MTR network expansion • To continually get updates from the property market 2 Hedonic model of price measurement Assumption Asset’s value can be derived from the value of its different characteristics Home Price Dependence on the values that buyers have placed on both qualitative and quantitative attributes Hedonic Estimation of the implicit market value of each Regression attributes of a property by comparing sample home prices with their associated characteristics, on a monthly basis Logarithm of transaction price will be used as independent variable for the regression model, whilst logarithm of dependent variables, such as building’s age, floor numbers, floor areas, and regional, district and estate building names will be selected in the model as controls for quality mix, apart from the time dummy variables (which are the most important part of the model), being employed. Methodology 3 The “Vigers Hong Kong Property Price Index Series” provides a perspective to understand movements in the Hong Kong private housing prices, based on the types or locations of properties. By applying the “Hedonic Regression Model”, the Index Series calculate property price changes relative to a base period at January 2017 (Level 100). Every published index represents an average of its latest six individual monthly indexes. All property attributes such as Building Age, Floor Number, Net Floor Size and Estates / Districts used in these calculations are consistent. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong SkyCity Marriott Hotel 11101 North Block 6, Belair Monte 11105 Kowloon City iclub Ma Tau Wai Hotel 11106 Central & Western Lan Kwai Fong Hotel@ Kau U Fong 11107 Wan Chai Best Western Hotel Causeway Bay 11108 Kowloon City Metropark Hotel Kowloon 11109 Kwun Tong IW Hotel 11110 Kwai Tsing Dorsett Tsuen Wan Hong Kong 11111 Eastern Ramada Hong Kong Grand View 11112 Kowloon City iclub Ma Tau Wai Hotel 11113 North Block 1, Dawning Views 11114 Islands Block 1, Coastal Skyline 11115 Central & Western Lan Kwai Fong Hotel@ Kau U Fong 11116 Central & Western Sing Fai Building 11118 Eastern Hoi Sing Mansion, Taikoo Shing 11120 Eastern Hoi Sing Mansion, Taikoo Shing 11121 Sai Kung Tak On House, Hau Tak Estate 11123 Sham Shui Po 15 Fuk Wing Street 11124 Kowloon City iclub Ma Tau Wai Hotel 11125 Yau Tsim Mong Dorsett Mongkok, Hong Kong 11127 Kwai Tsing Block 1, Regency Park 11128 Central & Western True Light Building 11129 Islands Hong Kong SkyCity Marriott Hotel 11130 Central & Western Yukon Court 11131 Central & Western Bishop Lei International House 11132 Central & Western 40 Conduit Road 11132 Sham Shui Po 15 Fuk Wing Street 11133 Central & Western May Tower I 11134 Kwai Tsing Yat King House, Lai King Estate 11135 Central & Western Yip Cheong Building, -

HONG KONG SERVICED APARTMENT GUIDE 2019 Sino Suites Ad Eng 215X275 Squarefoot 20190328-OP.Pdf 1 28/3/2019 4:00 PM

HONG KONG SERVICED APARTMENT GUIDE 2019 Sino Suites Ad_Eng_215x275_SquareFoot_20190328-OP.pdf 1 28/3/2019 4:00 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K CONTENTS 1 HONG KONG SERVICED APARTMENT GUIDE 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 20 32 38 40 52 OVERVIEW 4 Serviced Apartment Market Outlook 6 BUSTLING CITY The serviced apartment sector once 9 D’HOME again proves resilient, but for how 11 The Bauhinia long? 13 The Grand Blossom 15 Kornhill Apartments 17 The Luna 19 Harbour Plaza North Point 20 DESIGN GALORE 32 LUXE LIVING 21 V Residences & Serviced Apartments 34 Rosewood Residences Hong Kong 25 The Mercury 36 Four Seasons Place 27 Waterfront Suites Gateway Apartments 28 Little Tai Hang 37 Pacific Place Apartments Madera Residences Victoria Harbour Residence 30 Eight Kwai Fong Yin Serviced Apartments CONTENTS 2 HONG KONG SERVICED APARTMENT GUIDE 2019 Publisher TABLE OF CONTENTS REA Hong Kong Management Co. Limited. Website www.squarefoot.com.hk Country Manager, Hong Kong Kenneth Kent RELOCATION TIPS General Manager, Marketing & Brand 38 Finding Your Way Home Amanda Chase Sales Director Where exactly does one begin when relocating to Rebecca Tjouw Hong Kong? We sought expert advice for you. Group Editor Kenneth Chan Editor Annie Wong 40 URBAN NATURE Kenny Tong Assistant Editor 43 Harbour Plaza Resort City Catharina Cheung 45 Royal View Hotel Art Director 47 Eaton Residences Cato Sze 49 Regal Riverside Hotel Multimedia Designer Abby Tang 50 Hong Kong Gold Coast Residences Felder Chan Gary Chan The Ventris Distribution Operations Rita Lam Telephone Enquiries (852) 3198 1818 52 FEATURED SERVICES Advertising Enquiries 55 Patina Wellness [email protected] 56 The Unit General Enquiries [email protected] The Nate Facsimile 57 T Residence (852) 3198 1838 CHI 120 Produced by 58 Oootopia Paramount Printing Company Limited [email protected] 59 SERVICED APARTMENTS DIRECTORY FIND US ON 60 Hong Kong Island 63 Kowloon Disclaimer: Published by REA Hong Kong Management Co. -

Membership List

MEMBERSHIP LIST Hotel Address Tel.No. Fax.No. 99 Bonham 99 Bonham Strand, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 3940 1111 3940 1100 Auberge Discovery Bay Hong Kong 88 Siena Avenue Discovery Bay Lantau Island, Hong Kong 2295 8288 2295 8188 BEST WESTERN Grand Hotel 23 Austin Avenue, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon 3122 6222 2730 9328 BEST WESTERN Hotel Causeway Bay Cheung Woo Lane, Canal Road West, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2496 6666 2836 6162 BEST WESTERN Hotel Harbour View 239 Queen’s Road West, Hong Kong 2599 9888 2559 1266 BEST WESTERN PLUS Hotel Hong Kong 308 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 3410 3333 2559 8499 Best Western PLUS Hotel Kowloon 73-75 Chatham Road South, Tsimshatsui, Kowloon 2311 1100 2311 6000 Bishop Lei International House 4 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong 2868 0828 2868 1551 Butterfly on Morrison 39 Morrison Hill Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 3962 8333 3962 8322 Butterfly on Prat 21-23A Prat Avenue, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon 3962 8888 3962 8889 The Charterhouse Causeway Bay 209-219 Wanchai Road, Hong Kong 2833 5566 2833 5888 City Garden Hotel 9 City Garden Road, North Point, Hong Kong 2887 2888 2887 1111 The Cityview 23 Waterloo Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon 2783 3888 2783 3899 Conrad Hong Kong Pacific Place, 88 Queensway, Hong Kong 2521 3838 2521 3888 Cordis Hong Kong 555 Shanghai Street, Mongkok, Kowloon 3552 3388 3552 3322 Cosmo Hotel Hong Kong 375-377 Queen’s Road East, Wanchai, Hong Kong 3552 8388 3552 8399 Courtyard by Marriott Hong Kong 167 Connaught Road West, Hong Kong 3717 8888 3717 8228 Courtyard by Marriott Hong Kong Sha Tin 1 On Ping -

List of Buildings with Confirmed Cases of COVID-19

List of buildings with confirmed / probable cases of COVID-19 List of residential buildings in which confir med / probable cases have resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the last date of residence of the cases) District Building name Last date of Related confirmed / residence of the probable cases case(s) Wan Chai Block 1, Swiss Towers 6/3/2020 Case 110 Central and 341 Des Voeux Road West 6/3/2020 Case 116 Western Wan Chai Envoy Garden 8/3/2020 Case 114, 213 Yuen Long Tower 1, La Grove 7/3/2020 Case 115 Southern Block 28, Baguio Villa 9/3/2020 Case notified by the health authority of Canada and Case 117, 118 Tuen Mun On Hei House, Siu Hei Court 10/3/2020 Case 120, 121 Sha Tin Mau Lam House, Kwong Lam 10/3/2020 Case 122 Court Tsuen Wan Tower 7, Bellagio 10/3/2020 Case 123, 129 Kwun Tong Block T, Telford Gardens 10/3/2020 Case 125 Kwun Tong Block 26, Phase 2, Laguna 10/3/2020 Case 126,127 City Sai Kung Yee Ching House Yee Ming 10/3/2020 Case 58,128 Estate Kwai Tsing iPlace 12/3/2020 Case 130, 131,133 and 138 Central and Serene Court, 35 Sai Ning 12/3/2020 Case 132 Western Street Tai Po Ng Tung Chai, Lam Tsuen 13/3/2020 Case 134 Central and View Villa 13/3/2020 Case 135 Western Southern 18 Stanley Main Street 13/3/2020 Case 136 Wan Chai Block A, Tai Hang Terrace, 5 13/3/2020 Case 137 Chun Fai Road District Building name Last date of Related confirmed / residence of the probable cases case(s) Eastern Cornell Centre 13/3/2020 Case 139 Tai Po Heng Tai House, Fu Heng 13/3/2020 Case 119, 124, 140 Estate Sai -

Building List 20200301.Xlsx

根據香港法例第599C章正在接受強制檢疫人士所居住的大廈名單 根據《若干到港人士強制檢疫規例》(第599C章),除了豁免人士外,所有在到港當日之前的14日期間, 曾在內地逗留任何時間的人士,必須接受14天的強制檢疫。 List of buildings of the confinees under mandatory quarantine according to Cap. 599C of Hong Kong Laws According to Compulsory Quarantine of Certain Persons Arriving at Hong Kong Regulation (Cap. 599C), except for those exempted, all persons having stayed in the Mainland for any period during the 14 days preceding arrival in Hong Kong will be subject to compulsory quarantine for 14 days. (截至2020年2月26日晚上11時59分 As at 11:59 p.m., 26 February 2020) 區 地址 檢疫最後日期 (日/月/年) District Address End date of quarantine order (DD/MM/YYYY) 1 中西區 Central & 加多近山 27/02/2020 Western CADOGAN 2 中西區 Central & 西摩道11號福澤花園A座 27/02/2020 Western BLOCK A, THE FORTUNE GARDENS, NO.11 SEYMOUR ROAD 3 中西區 Central & 花園道55號愛都大廈3座 27/02/2020 Western BLOCK 3, ESTORIL COURT, NO.55 GARDEN ROAD 4 中西區 Central & 皇后大道西355-359號 27/02/2020 Western NO.355-359 QUEEN'S ROAD WEST 5 中西區 Central & 泰成大廈 27/02/2020 Western TAI SHING BUILDING 6 中西區 Central & 高雲臺 27/02/2020 Western GOLDWIN HEIGHTS 7 中西區 Central & 啟豐大廈 27/02/2020 Western KAI FUNG MANSION 8 中西區 Central & 堅城中心 27/02/2020 Western KENNEDY TOWN CENTRE 9 中西區 Central & 第三街208號毓明閣1座 27/02/2020 Western BLOCK 1, YUK MING TOWERS, NO.208 THIRD STREET 10 中西區 Central & 德輔道西333號 27/02/2020 Western NO.333 DES VOEUX ROAD WEST 11 中西區 Central & 德輔道西408A號 27/02/2020 Western NO.408A DES VOEUX ROAD WEST 12 中西區 Central & 蔚然 27/02/2020 Western AZURA 13 中西區 Central & 羅便臣道74號1座 27/02/2020 Western BLOCK 1, NO.74 ROBINSON ROAD 14 中西區 Central & BRANKSOME -

Driving Services Section

DRIVING SERVICES SECTION Taxi Written Test - Part B (Location Question Booklet) Note: This pamphlet is for reference only and has no legal authority. The Driving Services Section of Transport Department may amend any part of its contents at any time as required without giving any notice. Location (Que stion) Place (Answer) Location (Question) Place (Answer) 1. Aberdeen Centre Nam Ning Street 19. Dah Sing Financial Wan Chai Centre 2. Allied Kajima Building Wan Chai 20. Duke of Windsor Social Wan Chai Service Building 3. Argyle Centre Nathan Road 21. East Ocean Centre Tsim Sha Tsui 4. Houston Centre Mody Road 22. Eastern Harbour Centre Quarry Bay 5. Cable TV Tower Tsuen Wan 23. Energy Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 6. Caroline Centre Ca useway Bay 24. Entertainment Building Central 7. C.C. Wu Building Wan Chai 25. Eton Tower Causeway Bay 8. Central Building Pedder Street 26. Fo Tan Railway House Lok King Street 9. Cheung Kong Center Central 27. Fortress Tower King's Road 10. China Hong Kong City Tsim Sha Tsui 28. Ginza Square Yau Ma Tei 11. China Overseas Wan Chai 29. Grand Millennium Plaza Sheung Wan Building 12. Chinachem Exchange Quarry Bay 30. Hilton Plaza Sha Tin Square 13. Chow Tai Fook Centre Mong Kok 31. HKPC Buil ding Kowloon Tong 14. Prince ’s Building Chater Road 32. i Square Tsim Sha Tsui 15. Clothing Industry Lai King Hill Road 33. Kowloonbay Trademart Drive Training Authority Lai International Trade & King Training Centre Exhibition Centre 16. CNT Tower Wan Chai 34. Hong Kong Plaza Sai Wan 17. Concordia Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 35.