Joint Assessment North Hamgyong Floods 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tumen Triangle Documentation Project

THE TUMEN TRIANGLE DOCUMENTATION PROJECT SOURCING THE CHINESE-NORTH KOREAN BORDER Edited by CHRISTOPHER GREEN Issue Two February 2014 ABOUT SINO-NK Founded in December 2011 by a group of young academics committed to the study of Northeast Asia, Sino-NK focuses on the borderland world that lies somewhere between Pyongyang and Beijing. Using multiple languages and an array of disciplinary methodologies, Sino-NK provides a steady stream of China-DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea/North Korea) documentation and analysis covering the culture, history, economies and foreign relations of these complex states. Work published on Sino-NK has been cited in such standard journalistic outlets as The Economist, International Herald Tribune, and Wall Street Journal, and our analysts have been featured in a range of other publications. Ultimately, Sino-NK seeks to function as a bridge between the ubiquitous North Korea media discourse and a more specialized world, that of the academic and think tank debates that swirl around the DPRK and its immense neighbor. SINO-NK STAFF Editor-in-Chief ADAM CATHCART Co-Editor CHRISTOPHER GREEN Managing Editor STEVEN DENNEY Assistant Editors DARCIE DRAUDT MORGAN POTTS Coordinator ROGER CAVAZOS Director of Research ROBERT WINSTANLEY-CHESTERS Outreach Coordinator SHERRI TER MOLEN Research Coordinator SABINE VAN AMEIJDEN Media Coordinator MYCAL FORD Additional translations by Robert Lauler Designed by Darcie Draudt Copyright © Sino-NK 2014 SINO-NK PUBLICATIONS TTP Documentation Project ISSUE 1 April 2013 Document Dossiers DOSSIER NO. 1 Adam Cathcart, ed. “China and the North Korean Succession,” January 16, 2012. 78p. DOSSIER NO. 2 Adam Cathcart and Charles Kraus, “China’s ‘Measure of Reserve’ Toward Succession: Sino-North Korean Relations, 1983-1985,” February 2012. -

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

North Korea Today” Describing the Way the North Korean People Live As Accurately As Possible

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR NORTH KOREAN SOCIETY http://www.goodfriends.or.kr/[email protected] Weekly Newsletter No.374 Priority Release November 2010 [“Good Friends” aims to help the North Korean people from a humanistic point of view and publishes “North Korea Today” describing the way the North Korean people live as accurately as possible. We at Good Friends also hope to be a bridge between the North Korean people and the world.] ___________________________________________________________________________ Central Party Orders to Stop Collecting Rice for Military Provision Sound of Hailing at Farms at the News of No More Collection of Rice for Military Provision “Finally They Think of People” Meat Support Obligation to the Military Also Lifted “At least now we can fill our bellies with potatoes.” ___________________________________________________________________________ Central Party Orders to Stop Collecting Rice for Military Provision Every year when the harvest season approaches there were big conflicts at each regional farm between the military which tries to secure rice for military provision and farmers who refuse to hand over the rice they grew for the past one year. The conflicts are especially severe this year as the yields of harvest decrease because of the cold weather in the spring and the flood in the summer. In the case of North Hamgyong province it was reported that the level of discontent among farmers was serious enough to make the authorities worry. As the damage from flooding was so severe in the granary regions of North and South Hwanghae Provinces and North Pyongan Province it was decided that North Hamgyong Province was to provide rice for military provision first since it had better harvest. -

Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps

forced labour in North Korean Prison Camps Norma Kang Muico Anti-Slavery International 2007 Acknowledgments We would like to thank the many courageous North Koreans who have agreed to be interviewed for this report and shared with us their often difficult experiences. We would also like to thank the following individuals and organisations for their input and assistance: Amnesty International, Baspia, Choi Soon-ho, Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights (NKHR), Good Friends, Heo Yejin, Human Rights Watch, Hwang Sun-young, International Crisis Group (ICG), Mike Kaye, Kim Soo-am, Kim Tae-jin, Kim Yoon-jung, Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), Ministry of Unification (MOU), National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK), Save the Children UK, Tim Peters and Sarangbang. The Rufford Maurice Laing Foundation kindly funded the research and production of this report as well as connected activities to prompt its recommendations. Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Background 2 2. Border Crossing 3 3. Surviving in China 4 Employment 4 Rural Brides 5 4. Forcible Repatriation 6 Police Raids 6 Deportation 8 5. Punishment upon Return 8 Kukga Bowibu (National Security Agency or NSA) 9 Yeshim (Preliminary Examination) 10 Living Conditions 13 The Waiting Game 13 6. Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps 14 Nodong Danryundae (Labour Training Camp) 14 Forced Labour 14 Pregnant Prisoners 17 Re-education 17 Living Conditions 17 Food 18 Medical Care 18 Do Jipkyulso (Provincial Detention Centre) 19 Forced Labour 19 Living Conditions 21 Inmin Boansung (People's Safety Agency or PSA) 21 Formal Trials 21 Informal Sentencing 22 Released without Sentence 22 Arbitrary Decisions 22 Kyohwaso (Re-education Camp) 24 Forced Labour 24 Food 24 Medical Care 25 7. -

Emergency Appeal Final Report Democratic People’S Republic of Korea (DPRK) / North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Appeal Final Report Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) / North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal N°: MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of Issue: 26 March 2018 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date: 31 December 2017 Host National Society: Red Cross Society of Democratic Operation budget: CHF 5,037,707 People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK RCS) Number of people affected: 600,000 people Number of people assisted: 110,000 people (27,500 households) N° of National Societies involved in the operation: 19 National Societies: Austrian Red Cross, British Red Cross, Bulgarian Red Cross, China Red Cross, Hong Kong and Macau branches, Czech Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Finnish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross Society, New Zealand Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Red Crescent Society of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Red Cross of Monaco, Spanish Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Swiss Red Cross, the Canadian Red Cross Society, the Netherlands Red Cross, the Republic of Korea National Red Cross. The Governments of Austria, Denmark, Finland, Malaysia, Netherlands, Switzerland and Thailand, the European Commission - DG ECHO, and Czech private donors, the Korea NGO Council for Cooperation with North Korea, Movement of One Korea, National YWCA of Korea and the WHO Voluntary Emergency Relief Fund have contributed financially to the operation. N° of other partner organizations involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), ICRC, UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units Summary: This report gives an account of the humanitarian situation and the response carried out by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) during the period between 12 September 2016 and 31 December 2017, as per revised Emergency Operation Appeal (EPOA) with the support of International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) to meet the needs of floods affected families of North Hamgyong Province in DPRK. -

China Russia

1 1 1 1 Acheng 3 Lesozavodsk 3 4 4 0 Didao Jixi 5 0 5 Shuangcheng Shangzhi Link? ou ? ? ? ? Hengshan ? 5 SEA OF 5 4 4 Yushu Wuchang OKHOTSK Dehui Mudanjiang Shulan Dalnegorsk Nongan Hailin Jiutai Jishu CHINA Kavalerovo Jilin Jiaohe Changchun RUSSIA Dunhua Uglekamensk HOKKAIDOO Panshi Huadian Tumen Partizansk Sapporo Hunchun Vladivostok Liaoyuan Chaoyang Longjing Yanji Nahodka Meihekou Helong Hunjiang Najin Badaojiang Tong Hua Hyesan Kanggye Aomori Kimchaek AOMORI ? ? 0 AKITA 0 4 DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S 4 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Akita Morioka IWATE SEA O F Pyongyang GULF OF KOREA JAPAN Nampo YAMAJGATAA PAN Yamagata MIYAGI Sendai Haeju Niigata Euijeongbu Chuncheon Bucheon Seoul NIIGATA Weonju Incheon Anyang ISIKAWA ChechonREPUBLIC OF HUKUSIMA Suweon KOREA TOTIGI Cheonan Chungju Toyama Cheongju Kanazawa GUNMA IBARAKI TOYAMA PACIFIC OCEAN Nagano Mito Andong Maebashi Daejeon Fukui NAGANO Kunsan Daegu Pohang HUKUI SAITAMA Taegu YAMANASI TOOKYOO YELLOW Ulsan Tottori GIFU Tokyo Matsue Gifu Kofu Chiba SEA TOTTORI Kawasaki KANAGAWA Kwangju Masan KYOOTO Yokohama Pusan SIMANE Nagoya KANAGAWA TIBA ? HYOOGO Kyoto SIGA SIZUOKA ? 5 Suncheon Chinhae 5 3 Otsu AITI 3 OKAYAMA Kobe Nara Shizuoka Yeosu HIROSIMA Okayama Tsu KAGAWA HYOOGO Hiroshima OOSAKA Osaka MIE YAMAGUTI OOSAKA Yamaguchi Takamatsu WAKAYAMA NARA JAPAN Tokushima Wakayama TOKUSIMA Matsuyama National Capital Fukuoka HUKUOKA WAKAYAMA Jeju EHIME Provincial Capital Cheju Oita Kochi SAGA KOOTI City, town EAST CHINA Saga OOITA Major Airport SEA NAGASAKI Kumamoto Roads Nagasaki KUMAMOTO Railroad Lake MIYAZAKI River, lake JAPAN KAGOSIMA Miyazaki International Boundary Provincial Boundary Kagoshima 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 Kilometers Miles 0 10 20 40 60 80 ? ? ? ? 0 5 0 5 3 3 4 4 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names show n and t he designations us ed on this map do not imply of ficial endors ement or acceptance by the United N at ions. -

DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal n° MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of issue: 20 September 2016 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact: Marlene Fiedler Pak Un Suk Disaster Risk Management Delegate Emergency Relief Coordinator IFRC DPRK Country Office DPRK Red Cross Society Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date (timeframe): 31 August 2017 (12 months) Overall operation budget: CHF 15,199,723 DREF allocation: CHF 506,810 Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 600,000 people Direct: 28,000 people (7,000 families); Indirect: more than 163,000 people in Hoeryong City, Musan County and Yonsa County Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster From August 29th to August 31st heavy rainfall occurred in North Hamgyong Province, DPRK – in some areas more than 300 mm of rain were reported in just two days, causing the flooding of the Tumen River and its tributaries around the Chinese-DPRK border and other areas in the province. Within a particularly intense time period of four hours in the night between 30 and 31 August 2016, the waters of the river Tumen rose between six and 12 metres, causing an immediate threat to the lives of people in nearby villages. -

Special Economic Zones in the DPRK

Special Economic Zones in the DPRK This issue brief covers the history and recent upsurge of interest in special economic zones (SEZ) in the DPRK. For over twenty years, North Korea has periodically attempted to bolster its economy through the creation of SEZs, starting with the establishment of the Rason Special Economic Zone in the far northeast of the country in 1991. The two Koreas have also established two joint economic zones in the North, the Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC) and the Mount Kumgang Tourist Region (where operations are now suspended). All of North Korea’s SEZs established to date have been enclaves, attracting investment and foreign currency but not spurring greater economic growth in the rest of the country through the establishment of linkages or through a “demonstration effect” leading to more effective economic policies elsewhere. North Korea’s interest in developing SEZs has been sporadic, but several recent developments indicate that SEZs are becoming an increasingly important part of the country’s economic planning. Beginning in 2010, the DPRK renewed attempts to encourage investment and infrastructure developments in Rason, and more recently announced that new SEZs would be established in each province of the country. 1 This issue brief will cover the history of North Korean SEZs and review recent developments in this field. History of SEZs in North Korea Rason: North Korea’s first SEZ, the Rajin-Sonbong Free Economic and Trade Zone (later contracted to the Rason Economic and Trade Zone), was established in 1991, several years after North Korea first introduced laws allowing foreign investment. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

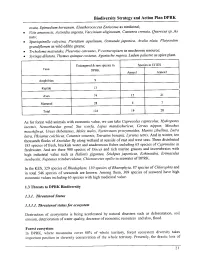

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Seismic Waves That Spread Through the Earth's Deep Interior

Seismic waves that spread through the Earth’s deep interior: BANG! or QUAKE! three stations at different distances from the sourc nces e ista 90º t d en er iff 60º d at s n o ti ta s e e r 30º h T CRUST (very thin) Seismic source CORE MANTLE 90º 60º 30º 90º 60º 30º 90º 60º 30º The wavefront position is shown after it has been traveling for several minutes. It continues to travel throughout the Earth's interior, bouncing off the core, and bouncing off the Earth's surface. 1.5 million seismic events since 1960, located by the International Seismological Centre on the basis of data from about 17,000 stations (up to ~ 6000 in any one year) 6L[GLIIHUHQWVWHSVLQQXFOHDUH[SORVLRQPRQLWRULQJ 'HWHFWLRQ GLGDSDUWLFXODUVWDWLRQGHWHFWDXVHIXOVLJQDO" $VVRFLDWLRQ FDQZHJDWKHUDOOWKHGLIIHUHQWVLJQDOVIURPWKHVDPH³HYHQW´" /RFDWLRQ ZKHUHZDVLW" ,GHQWLILFDWLRQ ZDVLWDQHDUWKTXDNHDPLQLQJEODVWDQXFOHDUZHDSRQWHVW" $WWULEXWLRQ LILWZDVDQXFOHDUWHVWZKDWFRXQWU\FDUULHGLWRXW" <LHOGHVWLPDWLRQ KRZELJZDVLW" MDJ 200 km HIA Russia 50°N 44°N HIA MDJ China USK BJT Chongjin 42° Japan 40° INCN KSRS MAJO 2006Oct09 MJAR Kimchaek SSE 30° 40° 120° 130° 140°E 126° 128° 130°E NIED seismic stations Hi-net 750 KiK-net 700 K-NET 1000 F-net 70 MDJ 200 km HIA Russia 50°N 44°N HIA MDJ China USK BJT Chongjin 42° Japan 40° INCN KSRS MAJO 2006Oct09 MJAR Kimchaek SSE 30° 40° 120° 130° 140°E 126° 128° 130°E Station Source crust mantle Pn - wave path (travels mostly in the mantle) Station Source crust mantle Pg - paths, in the crust, all with similar travel times Vertical Records at MDJ (Mudanjiang, -

Dpr Korea 2019 Needs and Priorities

DPR KOREA 2019 NEEDS AND PRIORITIES MARCH 2019 Credit: OCHA/Anthony Burke Democratic People’s Republic of Korea targeted beneficiaries by sector () Food Security Agriculture Health Nutrition WASH 327,000 97,000 CHINA Chongjin 120,000 North ! Hamgyong ! Hyeson 379,000 Ryanggang ! Kanggye 344,000 Jagang South Hamgyong ! Sinuiju 492,000 North Pyongan Hamhung ! South Pyongan 431,000 ! PYONGYANG Wonsan ! Nampo Nampo ! Kangwon North Hwanghae 123,000 274,000 South Hwanghae ! Haeju 559,000 REPUBLIC OF 548,000 KOREA PART I: TOTAL POPULATION PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE TARGETED 25M 10.9M 3.8M REQUIREMENTS (US$) # HUMANITARIAN PARTNERS 120M 12 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea targeted beneficiaries by sector () Food Security Agriculture Health Nutrition WASH 327,000 97,000 CHINA Chongjin 120,000 North ! Hamgyong ! Hyeson 379,000 Ryanggang ! Kanggye 344,000 Jagang South Hamgyong ! Sinuiju 492,000 North Pyongan Hamhung ! South Pyongan 431,000 ! PYONGYANG Wonsan ! Nampo Nampo ! Kangwon North Hwanghae 123,000 274,000 South Hwanghae ! Haeju 559,000 REPUBLIC OF 548,000 KOREA 1 PART I: TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: COUNTRY STRATEGY Foreword by the UN Resident Coordinator 03 Needs and priorities at a glance 04 Overview of the situation 05 2018 key achievements 12 Strategic objectives 14 Response strategy 15 Operational capacity 18 Humanitarian access and monitoring 20 Summary of needs, targets and requirements 23 PART II: NEEDS AND PRIORITIES BY SECTOR Food Security & Agriculture 25 Nutrition 26 Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) 27 Health 28 Guide to giving 29 PART III: ANNEXES Participating organizations & funding requirements 31 Activities by sector 32 People targeted by province 35 People targeted by sector 36 2 PART I: FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR In the almost four years that I have been in DPR Korea Despite these challenges, I have also seen progress being made. -

Emergency Appeal Revision Democratic People’S Republic of Korea / North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency appeal revision Democratic People’s Republic of Korea / North Hamgyong Province: Floods Revised Appeal n° MDRKP008 110,000 people to be assisted Appeal issued 20 September 2016 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK 506,810 Swiss francs advanced from DREF Revision n° 2 issued 1 November 2017 5,037,707 Swiss francs Appeal budget Appeal ends 31 December 2017 (16 months) 250,832 Swiss francs funding gap This Revised Emergency Appeal seeks 5,037,707 Swiss francs (reduced from 7,421,586 Swiss francs) to enable the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) to support the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) in delivering assistance and support to 110,000 people (reduced from 330,000 people) affected by the floods for 16 months. The operation focuses on health; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); shelter (including household non-food items); disaster risk reduction (DRR) and National Society capacity building. A major change includes a stronger focus on health activities such as household first aid kits and extended first aid training for volunteers. The revised plan reflects support already provided by the government to affected communities, as well as limitations that have resulted from inadequate funding. < Details are available in the Revised Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) > The disaster and the Red Cross and Red Crescent response to date 29-31 August 2016: More than 300mm of rain in North Hamgyong Province, coupled with the impact of Typhoon Lionrock, triggers the flooding of the Tumen River and its tributaries around the Chinese-DPRK border and other areas in the Province.