Director of Public Health Annual Report 2016 Acknowledgements and List of Contributors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 208 Newsletter

Systematic Innovation e-zine Issue 208, July 2019 In this month’s issue: Article – Case Study: EpiPens & Natasha’s Law Article – Constructed Crisis? Not So Funny – You Had One (Principle 17) Job Patent of the Month – Plasmonic Structures Best of The Month – Hooked Conference Review – ICSI 10 Wow In Music – Driving With The Brakes On Investments – Negative CTE Materials Generational Cycles – Jordan Peterson – Hero To Heroes Biology – Fogstand Beetle Short Thort News The Systematic Innovation e-zine is a monthly, subscription only, publication. Each month will feature articles and features aimed at advancing the state of the art in TRIZ and related problem solving methodologies. Our guarantee to the subscriber is that the material featured in the e-zine will not be published elsewhere for a period of at least 6 months after a new issue is released. Readers’ comments and inputs are always welcome. Send them to [email protected] ©2019, DLMann, all rights reserved Case Study: EpiPens & Natasha’s Law This is a photo of Natasha Ednan-Leparouse, recently boarded on a plane from Heathrow to Nice in the South of France. Approximately two hours after this photo was taken, Natasha was tragically pronounced dead. She suffered from extreme food allergies and had unwittingly, just before boarding her plane, eaten a sandwich that contained sesame seeds. As an allergy sufferer, Natasha had two EpiPens with her. Both were injected into her, but neither worked. The first story here is how come neither EpiPen worked. The simple answer to that question is that the design of EpiPens is not fit for purpose. -

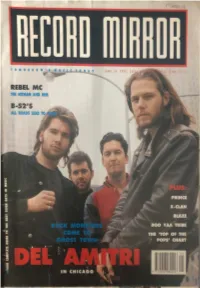

Record-Mirror-June-1990.Pdf

T OMOIIOW ' S ~ REBEL MC f • 11IE HffMAN AND HIM - B-52'5 ·~,~ • I " 1 I , I I :f I . I "'iii ::, :e z PRINCE X•CLAN BOO YAA TRIBE THE 'TOP OF THE • POPS' CHART ..... -·s Ill D 0 ► IN CHICAGO DEL AMITRI are straddling the Atlantic In their cowboy boots , with ' Move Away Jimmy Blue' In tho charts In Britain and 'Kiss Thi s Thing Goodbye' storming up the charts In America. Tim Nicholson (words) and Phil Ward (pictures) travelled to Chicago to taste th.a1~~,.-:, rock ' n' roll life THE NIGHT CHICAGO DIED The Windy City may be mighty pretty, but at night Chicago is a c·. - . house music came to die. Where once this city was the home of t 1aa • • • • now monsters of rock like Bon Jovi and Guns N' Roses 13 ha. foundations of a house that has been dismantled and rebuilt o~ " - by hyperactive Italian squatters. Del Amitri are at the forefront of the British foreign legGl\l. r:i-!!com~~ 4~ Chicago's empty clubs. They roam the foggy streets, trampm:1:l o dance u e a ,.,rw:F wherever a stray beat shows itself. They are no longer the t:.'il' • rigst_-JJ~e~. short back and sided youngsters of yore. They are d ~ e-~t r~k monsters. Well, kind of . Justin Currie, vocalist and all-round Del Amitri mouthpiece, !;ii , • enfunt~hf '-1':;:.ut their avoidance of barbers. " In the Eighties it became a purE ng,-~11 square-jawed guys and pretty, flouncy girls ... yeuch! Havi ~ hairJOS1/' 0 like being a blonde in a band all over again. -

Mountain Stage Guest Artist List

MOUNTAIN STAGE GUEST ARTIST LIST 1981 March Bob Thompson Jazz Trio, Putnam County Pickers 1983 December Larry Parson’s Chorale, Bob Thompson Jazz Trio, John Pierson 1984 January Currence Brothers, Ethel Caffie-Austin Singers, Terry Wimmer February Rhino Moon, Moloney, O’Connell & Keane, Alan Klein, Robert Shafer March Trapezoid, Charleston String Quartet, Bonnie Collins, April Stark Raven, Joe Dobbs/Friends, Alan Freeman, Joe McHugh May Hot Rize, Red Knuckles & Trailblazers, Karen McKay, Alan/Jeremy Klein June Norman Blake/Rising Fawn Ensemble, Appalachian String Quartet, Elmer Bird, Jeff and Angela Scott July Still Portrait, Everett Lilly/Appalachian Mountain, Sweet Adelines August Bill Danoff, Ann Baker/Bob Thompson Trio, Bob Shank, Alice Rice September Clan Erdverkle, Ron Sowell, Tracy Markusic, Shirley Fisher October Critton Hollow String Band, Tom Church, Marc & Cheryl Harshman November Turley Richards, Night Sky, Mountain Stage Regulars December (1 hr. Christmas special) West Virginia Brass, Bob Thompson, Devon McNamara 1985 January Turley Richards, West Virginia Brass, Bonnie Collins February Whetstone Run, Lucky Jazz Band, Alice Rice March Alex de Grassi, Nat Reese, Maggie Anderson April Guy Clark, Trapezoid, Marc Harshman May Bob Thompson, Ann Baker, Paul Skyland, Devon McNamara June 1 (Spoleto-Chas, SC) Hot Rize, Red Knuckles, John Roberts/Tony Barrand, Moving Star Singers June John McEuen, Mountain Thyme, John Rosenbohm, Bonnie Collins July Bill Danoff, Steadfast, Faith Holsaert August Buster Coles, Bing Brothers, Bob Baber -

![Intro: [F] [F] Post Office Clerks Put up Signs Saying Position [Dm] Closed and [F] Secretaries Turn Off Typewriters and Put On](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5905/intro-f-f-post-office-clerks-put-up-signs-saying-position-dm-closed-and-f-secretaries-turn-off-typewriters-and-put-on-4315905.webp)

Intro: [F] [F] Post Office Clerks Put up Signs Saying Position [Dm] Closed and [F] Secretaries Turn Off Typewriters and Put On

Nothing Ever Happens (Justin Currie – Del Amitri) Intro: [F] [F] Post office clerks put up signs saying position [Dm] closed And [F] secretaries turn off typewriters and put on their [Dm] coats And [Bb] janitors padlock the [F] gates … for se- [C] curity guards to pa- [Bb] trol And [Bb] bachelors phone up their [F] friends for a drink While the [C] married ones turn on a [Bb] chat show And they'll [F] all be lonely to- [Bb] night and lonely to- [F] morrow “Gentlemen, Time please, you know we can't serve any- [Dm] more" Now the [F] traffic lights change to stop, when there's nothing to [Dm] go And by [Bb] five o'clock everything's [F] dead, … and [C] every third car is a [Bb] cab And [Bb] ignorant people [F] sleep in their beds Like the [C] doped white mice in the [Bb] college lab [F] Nothing ever [Bb] happens, [F] nothing happens at [Bb] all The [Dm] needle returns to the [Bb] start of the song And we [C] all sing along like be- [Bb] fore And we'll [F] all be lonely to- [Gm] night and lonely to- [F] morrow [F] Telephone exchanges click while there's nobody [Dm] there The [F] martians could land in the car park and no one would [Dm] care [Bb] Closed-circuit cameras in [F] department stores shoot the [C] same movie every [Bb] day And the [Bb] stars of these films neither [F] die nor get killed just sur- [C] vive constant "Action. Re- [Bb] play" [F] Nothing ever [Bb] happens, [F] nothing happens at [Bb] all The [Dm] needle returns to the [Bb] start of the song And we [C] all sing along like be- [Bb] fore And we'll [F] all be lonely to- [Gm] night and lonely to- [F] morrow Instrumental: [G] / / / [Dm] / / / [G] / / / [Dm] / / / [F] / [G] / [F] / [G] / [F] / / / And [F] bill hoardings advertise products that nobody [Dm] needs While [F] 'Angry-From-Manchester' writes to complain about [Dm] all the repeats on T.V. -

The Del Amitri Story

I ■ I I The Del Arnitri Co111panion Issue 6 November 1997 EDITORS' NOTES: They've had a hard time breaking the Deis to the next level in the U.S. for some unknown reason that has nothing to do with NASHVILLE, USA • Things are still going great here at l&P how talented they believe the band to be or how nu:h they Ama's at <:N6f 400 Slbscribers in the UK /Eu~ and I'm at want to sl.ppOrt the band He knows that fans blame the labet about 250 from the U S /Canada (and a few others from for the Deis not breaking bigger 1n the US , and even said he aromdthev«>r1dl takes the blame himself, which I thought was gracious but By far the best thing f()( me in this issue 1s that this is the first undeserved. time we've had one of the band mermers participate k. you'll It's dfficult for fans to understand that no matter how nu:h the see, Justin judged our lyric contest and was so wonderlul in lci>el may want to support a band with as many resources as writing in to explain how he Judged the Sli>missioos and why possible, it must follow a certain path that is responsible from a he picked the winning entry. And to add to the excHemen~ we business pernpective. So I guess my <µ35tion to all the have the excellent interview with Deis Production Manager naysayers out there is ... "If you don't like A&M (and if you Derek McVay by Karen Nesbitt and Lori Royal-Gordon don't, have you checked out the success of their current roster Thanks so much to both Justin and Derek f()( their time and lately?), what label would you rather see Del Amitri signed Sl.W(Xtofl&P. -

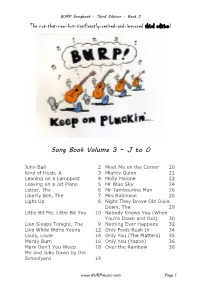

The Not-That-New-But-Significantly-Revised-And-Improved Third Edition! Song Book Volume 3 – J to O

BURP Songbook – Third Edition – Book 3 The not-that-new-but-significantly-revised-and-improved third edition! Song Book Volume 3 – J to O John Ball 2 Meet Me on the Corner 20 Kind of Hush, A 3 Mighty Quinn 21 Leaning on a Lamppost 4 Molly Malone 22 Leaving on a Jet Plane 5 Mr Blue Sky 24 Letter, The 6 Mr Tambourine Man 26 Liberty Bell, The 7 Mrs Robinson 28 Light Up 8 Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, The 29 Little Bit Me, Little Bit You 10 Nobody Knows You (When You're Down and Out) 30 Lion Sleeps Tonight, The 9 Nothing Ever Happens 32 Live While We’re Young 12 Only Fools Rush In 34 Louis, Louie 14 Only You (The Platters) 35 Mardy Bum 16 Only You (Yazoo) 36 Mary Don't You Weep 18 Over the Rainbow 38 Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard 19 www.BURPmusic.com Page 1 BURP Songbook – Third Edition – Book 3 John Ball (Sydney Carter) [G] Who’ll be the lady, [C] who will be the [D] lord, [C] When we are ruled by the [D] love of another? [G] Who’ll be the lady, [C] who will be the [D] lord, In the [C] light that is coming in the [D] morn- [G] ing. Chorus: [D] Sing, John Ball and tell it to them all, Long live the day that is dawning! And I'll [G] crow like a cock, I'll [C] carol like a [D] lark, In the [C] light that is coming in the [D] morn- [G] ing. -

Winners Hot New Releases

sue 543 $6.00 May 19, 1997 Volume 11 HANSON WINNERS EARPICKS BREAKOUTS ILDCARD HANSON Mercury EN GUE EW/EEG COUNTING CROWS DGC SHERYL CROW A&M THIRD EYE BLIND Elek/EEG TIW SPROCKET Col/CRG BEE GEES Poly/A&M See P. e 14 For Details SHERYL CROW A&M INDIGO GIRLS Epic JON BON JOVI Mercury MEREDITH BROOKS Capitol JON BON JOVI Mercury BOB CARLISLE Jive COUNTING CROWS DGC STEADY MOBB'N Priority SISTER HAZEL Universal M.M. BOSSTONES Mercury HOT NEW RELEASES AALIYAH ALISHA'S ATTIC BABYFACE COLLECTIVE SOUL EN VOGUE 4 Page Letter I Am, I Feel How Come, How Long Listen Whatever Bel/MI/MI G 98021 Mercury N/A Epic N/A AtI/Atl G 84006 EW/EEG N/A JAMIROQUAI JONNY LANG PAUL McCARTNEY MASTA P Virtual Insanity Lie To Me The World Tonight If I Could Change WORK N/A A&M N/A Capitol N/A NI/Priority 53273 REAL Mc SHADES STEVE WINWOOD I Wanna Come (With You) Serenade Spy In The House Of Love Arista N/A Motown 3746-32062-2 Virgin N/A 117-- World Party It Is Time THE ENCLAVE 936 Broadway new york.n.y 10010, www.the-enclave.com May 19, 1997 Volume 11 Issue 543 $6.00 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher LENNY BEER VIBE-RATERS 4 Winning Ticket Editor In Chief Hanson are in the middle of somewhere and Meredith Brooks TONI PROFERA moves to the edge while the debuting Sammy Hagar and Executive Editor Supergrass grow. DAVID ADELSON Vice President/Managing Editor KAREN GLAUBER MOST POWERFUL SONGS 6 Senior Vice President Spice Girls just want to have fun at #1 over runner-up Mary J. -

(And Recording) Studios

Anderson, Robert (2015) Strength in numbers: a social history of Glasgow's popular music scene (1979-2009). PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/6459/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Strength in Numbers A Social History of Glasgow’s Popular Music Scene (1979-2009) Robert Anderson BA (Hons), PGCE, MEnvS, DipEd Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow June 2015 © Robert Anderson, 2015 2 Abstract In 2004, US Time magazine named Glasgow Europe’s ‘capital of rock music’ and likened it to Detroit in its Motown heyday (Porter, 2004). In 2008 UNESCO awarded Glasgow the title of ‘City of Music’ and the application dossier submitted in support of this title noted the importance of rock and pop for the city’s musical reputation. Since the late 1970s a large number of bands have emerged from (or been associated with) the city, yet little academic research has been carried out to determine the factors behind this phenomenon. -

The Town House Hamilton

The Town House Hamilton Winter Season 2021 Customer Notice South Lanarkshire Leisure and Culture would like to offer our sincere thanks to all of our customers for their support and understanding at this difficult time. We have produced this brochure with the intention and hope of staging all of the performances listed, however given the current and ongoing uncertainty that we are all facing, it should be noted that all of the advertised events are subject to change, rescheduling or cancellation. The information contained in this brochure was correct at the time of going to print. We would encourage all of our customers to continue to purchase tickets for forthcoming events. We look forward to welcoming you back into our Venues at the very earliest opportunity. We can only do this with your continued support. Thank you Welcome to our Spring Season 2021 We are always interested in receiving comments and suggestions from customers. You can do this by completing a customer comments form when you are on the premises and handing it in at our reception. You can write to us at the address below or email us at [email protected] On behalf of all of the staff here, we hope you enjoy this seasons productions and we look forward to welcoming you on your next visit to The Town House. Charlie Ingham Venue Manager to Coatbridge Reproduction by permission of and Edinburgh Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. A725 Directions Raith Interchange © Crown copyright and database Junction 5 right 2020. All rights reserved. 102 Cadzow Street, Ordnance Survey Licence ➜ to Glasgow number 100020730 Hamilton ML3 6HH Strathclyde Country Park The Town House is a short walk A725 from Hamilton Central Station and Hamilton Bus Station. -

Www .Maver Ic K

JANUARY/FeBRUARY 2014 www.maverick-country.com MAVERICK FROM THE EDITOR... MEET THE TEAM Editor t is with a great deal of sadness, that I acknowlege that this will be my last issue as Alan Cackett editor of Maverick. I have always believed that when you no longer enjoy doing 24 Bray Gardens, Loose, Maidstone, Kent, ME15 9TR, UK something, then it’s time to stop and look to do something di erent. I have had a 01622 744481 Igood run as editor, and now is the time to hand over to someone younger. Someone who [email protected] can hopefully take the magazine forward, embracing country music’s future whilst not Managing Editor overlooking its huge legacy of the past. I know that the new editor Laura Bethell who Michelle Teeman 01622 823920 worked with me for 5 years, 2 as my deputy editor, will do just that. [email protected] It was just over 47 years ago that I edited and published Britain’s rst regular monthly country music magazine. Looking back that was quite an audacious and bold undertaking Designer Laura Bethell for a teenager from a council house estate who le school at 15. Some of the original 01622 823922 readers of Country Music Monthly are still around and have continued to follow my writing [email protected] and views on the music as readers of Maverick. ere was a time when I not only knew Editorial Assistant many of the Maverick readers’ names but had a personal contact with them, but recently Chris Beck I’ve lost touch and I have to say that I miss the chats that we used to have when they phoned Project Manager up to renew their subscriptions. -

Remembering BUNTING Festival 2020 February 20-23, 2020

Remembering BUNTING Festival 2020 February 20-23, 2020 The Remembering Bunting Festival Edward Bunting 1773-1843 BELFAST is produced by Mention the name Edward Bunting in traditional music and Irish history circles and the majority of those engaged will claim at least some knowledge of the man. So who is this Edward Bunting and just what is his claim to fame? Dún Uladh, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann’s Born in Armagh in 1773, Edward Bunting was a prolific collector of traditional songs and tunes. His three volumes of the Regional Cultural and Heritage Centre Ancient Music of Ireland, were published in 1796, 1809 and 1840 respectively. based in Omagh, funded by Edward began formal music studies in Drogheda at the young age of seven. Edward showed such great promise that he was, by age eleven, scouted and became apprentice to, William Ware, organist of St. Anne’s Parish, now otherwise known as The Executive Office, through the Together Building a United Community Programme Belfast Cathedral. Later, he became the church organist at St. George’s Parish Church, High Street before the last chapter of and his professional and personal life took place in Dublin, where he is buried. The Republic of Ireland’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the It can be deduced that Edward Bunting, from all accounts was born to a Catholic mother and a Church of Ireland father. Reconciliation Fund Whilst in Belfast, he resided at the home of the famous McCracken family and became somewhat of an “adopted’ member of that Presbyterian family having stayed with them for thirty-five formative years! At age nineteen, with the shared interests For more information contact and formidable support of the siblings, Mary Ann and Henry Joy McCracken, the classically trained and most competently Outreach Officer - Karen D’Aoust skilled young Bunting was put to task to transcribe the music presented at the Belfast Harpers’ Gathering in 1792 for the purpose of preserving what was referred to as “ancient melodies of Ireland”. -

Darvel Music Festival Darvel Town Hall 6Th to 28Th May 2011 That Time of Year Again

DARVEL MUSIC FESTIVAL DARVEL TOWN HALL 6TH TO 28TH MAY 2011 THAT TIME OF YEAR AGAIN... ...On behalf of the Darvel Music Company I would like to extend a very warm welcome to all of our regular festival patrons and a special Darvel welcome to those of you who may be attending the event for the first time as well as our many visitors from overseas and across the UK. I hope that you will enjoy the “Darvel Experience” and that you are impressed by the intimate setting of our venue and the fantastic range of artistes who will be performing at our 10th anniversary concerts throughout the month of May. I am sure you will agree that we have a superb line-up this year and with over twenty five international and national performers covering a wide range of musical genres including; blues, soul, country, bluegrass, rock, pop, traditional and funk, there is something to enthuse all kinds of music aficionados. Please support us in our efforts to sustain ‘live’ music in Darvel by purchasing limited edition festival merchandise, guitar raffle tickets and if so inclined please consider becoming either an individual/family or business patron of the music festival. Thank you Sheila McKenna – Festival Director THE DMF TEAM Director Programme Design Sheila McKenna Scott McDonald of Creative Colour Bureau Producer Photography Neil McKenna Nathan Balls Sound and Lights Festival Committee Simon & George Payling Lynne McCubbin, Hugh Morton, Anne of Smalltown Audio Fonteyne-Aspeslagh, Lisa Cunningham Rachel Clinton, Alan McFedries, Sofie Bar Services Aspeslagh,