University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

November/December 2005 Issue 277 Free Now in Our 31St Year

jazz &blues report november/december 2005 issue 277 free now in our 31st year www.jazz-blues.com Sam Cooke American Music Masters Series Rock & Roll Hall of Fame & Museum 31st Annual Holiday Gift Guide November/December 2005 • Issue 277 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum’s 10th Annual American Music Masters Series “A Change Is Gonna Come: Published by Martin Wahl The Life and Music of Sam Cooke” Communications Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees Aretha Franklin Editor & Founder Bill Wahl and Elvis Costello Headline Main Tribute Concert Layout & Design Bill Wahl The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and sic for a socially conscientious cause. He recognized both the growing popularity of Operations Jim Martin Museum and Case Western Reserve University will celebrate the legacy of the early folk-rock balladeers and the Pilar Martin Sam Cooke during the Tenth Annual changing political climate in America, us- Contributors American Music Masters Series this ing his own popularity and marketing Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, November. Sam Cooke, considered by savvy to raise the conscience of his lis- Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, many to be the definitive soul singer and teners with such classics as “Chain Gang” Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane crossover artist, a model for African- and “A Change is Gonna Come.” In point Verh and Ron Weinstock. American entrepreneurship and one of of fact, the use of “A Change is Gonna Distribution Jason Devine the first performers to use music as a Come” was granted to the Southern Chris- tian Leadership Conference for ICON Distribution tool for social change, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the fundraising by Cooke and his manager, Check out our new, updated web inaugural class of 1986. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

SMT Sweelinck Paper Text SHORT V2

SMT Graduate Workshop Peter Schubert: Renaissance Instrumental Music November 7, 2014 Derek Reme! Musical Architecture in Three Domains: Stretto, Suspension, and Diminution in Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia is among the most famous keyboard works of the sixteenth century.1 It served as a model for instrumental polyphony that was imitated throughout Europe in the seventeenth century.2 The fantasia's subject is treated in augmentation and diminution in four rhythmic levels and also in four-voice stretto. The initial stretto passage, which is repeated in diminution in the final climax of the piece, contains an unusual accented dissonance; in this style, accented dissonance is reserved only for suspensions. There are three metrical levels of suspensions used throughout the piece, which parallel the four rhythmic levels of the subject's augmentation and diminution – only a whole note suspension is missing. I propose that the unusual accented dissonance in the first four-voice stretto passage is actually a rearticulated whole note suspension, representing the missing fourth metrical level in that domain. Therefore, this stretto passage combines two domains at their fourth and most heightened level: stretto in four voices and suspension at the whole note. This passage also represents a structural "pillar," which, through its repetition, divides the piece into three large sections. In addition, the middle section contains two analogous "internal pillars," which further subdivide the middle into three subsections. The last large-scale section, the climax, introduces subject stretto at the eighth note level, or !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 Harold Vogel, "Sweelinck's 'Orfeo' Die 'Fantasia Crommatica,'" Musik in die Kirche, No. -

Notes, Rhythm, and Meter Notes

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music NOTES, RHYTHM, AND METER NOTES: Notes represent a duration or length of a sound. Notes consist of the head the stem and the flag or beam. note = head + stem + flag NOTE HEADS: The head of the note should be written as an oval (not a round circle) and should be centered on the line or space of the staff that represents the note. STEMS: Stems are notated on the right side of the note head and are ascending if the note head is on the 3rd line of the staff or below that line. Stems are notated on the left side of the note head and are descending if the note is on the 3rd line of the staff or above that line. Stems should be about 1 octave in length and should be straight up and down (not slanted). FLAGS: Flags are notated to the right of the stem whether the stem is on the right or left side of the note head. BEAMS: Notes should be beamed together to show the beat. Beams should therefore not cross beats. Beams should be straight lines, not curves. Beams may be slanted ascending or descending according to the contour of the notes. Beaming notes together may result in shortened or elongated stems on some notes. If beaming eighth notes and sixteenth notes together, sixteenth note beams should always go inside the beginning and ending stems. DURATIONS: Notes can have various durations and various names: American British (older version) double-whole breve whole semi-breve half minim quarter crotchet eighth quaver sixteenth semi-quaver thirty-second demi-semi-quaver sixty-fourth hemi-demi-semi-quaver These notes look like the following: double whole half quarter 8th 16th 32nd 64th whole In the above list, each note duration is one-half the duration of the preceding note duration. -

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription Mary Turner De Garmo Second Edition Revised and edited by Lawrence R. Smith Music Braille Transcriber Bettye Krolick Music Braille Consultant Beverly McKenney Music Braille Transcriber Sandra Kelly Music Braille Advisor Volume I National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped The Library of Congress Washington, DC 2005 Contents VOLUME I Foreword to the 1974 Edition . xi Preface to the 2005 Edition . xii Acknowledgments . xiii How to Use This Book . xiv Related Resources . xiv Overall Plan . xiv References to MBC-97 . xiv Using Computer Assistance . xv Taking the Course . xv References . xvi PART ONE: Basic Procedures and Transcribing Single-Staff Music 1 Formation of the Braille Note . 1 2 Eighth Notes, the Eighth Rest, and Other Basic Signs . 3 General Procedures . 4 Examples for Practice . 4 Procedures Specific to This Book . 7 Drills for Chapter 2 . 7 Exercises for Chapter 2 . 9 3 Quarter Notes, the Quarter Rest, and the Dot . 11 Examples for Practice . 11 Proofreading . 13 Drills for Chapter 3 . 13 Exercises for Chapter 3 . 15 4 Half Notes, the Half Rest, and the Tie . 17 Drills for Chapter 4 . 19 Exercises for Chapter 4 . 20 5 Whole and Double Whole Notes and Rests, Measure Rests, and Transcriber-Added Signs . 23 Various Print Methods for Showing Consecutive Measure Rests . 26 Reading Drill . 28 Drills for Chapter 5 . 30 Exercises for Chapter 5 . 31 6 Accidentals . 33 Directions for Brailling Accidentals . 33 Examples for Practice . 34 Drills for Chapter 6 . 35 i Exercises for Chapter 6 . 37 7 Octave Marks . 39 The Seven Octave Marks . -

4Th Grade Music Vocabulary

4th Grade Music Vocabulary 1st Trimester: Rhythm Beat: the steady pulse in music. Note: a symbol used to indicate a musical tone and designated period of time. Whole Note: note that lasts four beats w Half Note: note that lasts two beats 1/2 of a whole note) h h ( Quarter Note: note that lasts one beat 1/4 of a whole note) qq ( Eighth Note: note that lasts half a beat 1/8 of a whole note) e e( A pair of eighth notes equals one beat ry ry Sixteenth Note: note that lasts one fourth of a beat - 1/16 of a whole note) s s ( A group of 4 sixteenth notes equals one beat dffg Rest: a symbol that is used to mark silence for a specific amount of time. Each note has a rest that corresponds to its name and how long it lasts: Q = 1 = q = 2 = h = 4 = w H W Rhythm: patterns of long and short sounds and silences. 2nd Trimester: Melody/Expressive Elements and Symbols Dynamics: the loudness and quietness of sound. Pianissimo (pp): very quiet or very soft. Piano (p ): quiet or soft. Mezzo Piano (mp): medium soft Mezzo Forte (mf): medium loud Forte (f ): loud/strong. Fortissimo (ff): very loud/strong Crescendo (cresc. <): indicates that the music should gradually get louder. Decrescendo (decresc. >): indicates that the music should gradually get quieter. Tempo: the pace or speed of the music Largo: very slow. Andante: walking speed Moderato: moderately, medium speed Allegro: quickly,fast Presto: very fast Melody: organized pitches and rhythm that make up a tune or song. -

1 an Important Component of Music Is the Rhythm, Or Duration of The

1 An important component of music is the rhythm, or duration of the sounds. We designate this with whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, etc., the names of which indicate the relative duration of notes (e.g., a half note lasts four times as long as an eighth note). ∼ 3 4 It isd of d courset t necessary to specify the actual (not just relative) duration of sounds. There are several ways to do this, we shall discuss two which reflect the manner in which music is displayed. Printed music groups notes into measures, and begins each line with a time signature which looks like a fraction, and specifies the number of notes in each measure. For example, the time signature 3/4 specifies that each measure contains three quarter notes (or six eighth notes, or a half note and a quarter note, or any collection of notes of equal total duration). (The above schematic is not divided into measures; a whole note would not fit within a measure in 3/4 time.) Indeed, you cannot tell from looking just at a measure whether the time signature is 3/4 or 6/8, but both the top and bottom of the time signature are important for specifying the nature of the rhythm. The top number specifies how many beats (or fundamental time units) there are in a measure, and the bottom number specifies which note represents the fundamental time unit. For example, 3/4 time specifies three beats to a measure with a quarter note representing one beat, 6/8 time specifies six beats to a measure with an eighth note representing one beat. -

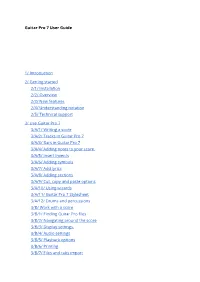

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window. -

Concerto for Alto Saxophone

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Dissertations 2018 A Conductor’s and Performer’s Guide to Steven Bryant’s Concerto for Alto Saxophone Chester Jenkins Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Jenkins, Chester, "A Conductor’s and Performer’s Guide to Steven Bryant’s Concerto for Alto Saxophone" (2018). Faculty Dissertations. 137. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_dissertations/137 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Conductor’s and Performer’s Guide to Steven Bryant’s Concerto for Alto Saxophone D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chester James Jenkins, M.M., B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee Prof. Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Daryl Kinney Dr. Russel Mikkelson Prof. Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Chester James Jenkins 2018 2 Abstract The purpose of this work is to examine the history and compositional elements of Steven Bryant’s Concerto for Alto Saxophone and Wind Ensemble, as well as to provide analysis and performance considerations for the work. The personal and idiosyncratic nature of the composition is important to understand for an effective performance of the concerto. -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold

Performance Practice Review Volume 17 | Number 1 Article 4 Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Jerold, Beverly (2012) "Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 17: No. 1, Article 4. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.201217.01.04 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol17/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold Copyright © 2012 Claremont Graduate University Ever since antiquity, the human species has been drawn to numbers. In music, for example, numbers seem to be tangible when compared to the language in early musical texts, which may have a different meaning for us than it did for them. But numbers, too, may be misleading. For measuring time, we have electronic metronomes and scientific instruments of great precision, but in the time frame 1630-1800 a few scientists had pendulums, while the wealthy owned watches and clocks of varying accuracy. Their standards were not our standards, for they lacked the advantages of our technology. How could they have achieved the extremely rapid tempos that many today have attributed to them? Before discussing the numbers in sources thought to support these tempos, let us consider three factors related to technology: 1) The incalculable value of the unconscious training in every aspect of music that we gain from recordings.