Concerto for Alto Saxophone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

November/December 2005 Issue 277 Free Now in Our 31St Year

jazz &blues report november/december 2005 issue 277 free now in our 31st year www.jazz-blues.com Sam Cooke American Music Masters Series Rock & Roll Hall of Fame & Museum 31st Annual Holiday Gift Guide November/December 2005 • Issue 277 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum’s 10th Annual American Music Masters Series “A Change Is Gonna Come: Published by Martin Wahl The Life and Music of Sam Cooke” Communications Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees Aretha Franklin Editor & Founder Bill Wahl and Elvis Costello Headline Main Tribute Concert Layout & Design Bill Wahl The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and sic for a socially conscientious cause. He recognized both the growing popularity of Operations Jim Martin Museum and Case Western Reserve University will celebrate the legacy of the early folk-rock balladeers and the Pilar Martin Sam Cooke during the Tenth Annual changing political climate in America, us- Contributors American Music Masters Series this ing his own popularity and marketing Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, November. Sam Cooke, considered by savvy to raise the conscience of his lis- Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, many to be the definitive soul singer and teners with such classics as “Chain Gang” Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane crossover artist, a model for African- and “A Change is Gonna Come.” In point Verh and Ron Weinstock. American entrepreneurship and one of of fact, the use of “A Change is Gonna Distribution Jason Devine the first performers to use music as a Come” was granted to the Southern Chris- tian Leadership Conference for ICON Distribution tool for social change, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the fundraising by Cooke and his manager, Check out our new, updated web inaugural class of 1986. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JON HENDRICKS NEA Jazz Master (1993) Interviewee: Jon Hendricks (September 16, 1921 - ) and, on August 18, his wife Judith Interviewer: James Zimmerman with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 17-18, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 95 pp. Zimmerman: Today is August 17th. We’re in Washington, D.C., at the National Portrait Galley. Today we’re interviewing Mr. Jon Hendricks, composer, lyricist, playwright, singer: the poet laureate of jazz. Jon. Hendricks: Yes. Zimmerman: Would you give us your full name, the birth place, and share with us your familial history. Hendricks: My name is John – J-o-h-n – Carl Hendricks. I was born September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, the ninth child and the seventh son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. My father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the AME Church. Zimmerman: Who were your brothers and sisters? Hendricks: My brothers and sisters chronologically: Norman Stanley was the oldest. We call him Stanley. William Brooks, WB, was next. My sister, the oldest girl, Florence Hendricks – Florence Missouri Hendricks – whom we called Zuttie, for reasons I never For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 really found out – was next. Then Charles Lancel Hendricks, who is surviving, came next. Stuart Devon Hendricks was next. Then my second sister, Vivian Christina Hendricks, was next. Then Edward Alan Hendricks came next. -

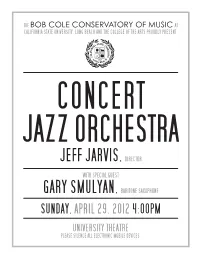

Jeff Jarvis,Director

CONCERT JAZZ ORCHESTRA JEFF JARVIS, DIRECTOR WITH SPECIAL GUEST GARY SMULYAN, BARITONE SAXOPHONE SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2012 4:00PM UNIVERSITY THEATRE PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. TONIGHT’S PROGRAM GENTLY / Bob Mintzer This well-crafted original is the title track of a recording of the Bob Mintzer Big Band. This recording project was unique in that the horn section stood in a circle surrounding a specially designed ribbon microphone that was extremely sensitive and accurate. This microphone would not accept loud dynamic levels, so Bob Mintzer wrote material that showcased the band playing at softer dynamics, which resulted in frequent use of muted brass, flugelhorns, and woodwinds. Today’s soloists include Josh Andree (tenor sax) and Will Brahm (guitar). THEN AND NOW / George Stone This terrific original composition and arrangement is featured on a recent recording of the George Stone Big Band entitled “The Real Deal”, performed by a collection of Southern California’s finest studio musicians. George’s music is frequently featured at our concerts because of its superior quality, both from a compositional standpoint and also in terms of orchestration. This piece has it all—melodic integrity, intense rhythms, lush harmonies, and sufficient solo space. Today’s soloists include Eun young Koh (piano), Josh Andree (tenor sax), Will Brahm (guitar), and Daniel Hutton (alto sax). CHINA BLUE / Jeff Jarvis Originally composed as a commission for a big band in Williamsburg VA, the work features a winding trumpet melody supported by muted trombone parts, warm flugelhorn lines, and beautiful woodwind parts played by the saxophone section. The piece proves challenging since the musicians are faced with executing exposed parts with delicacy and restraint. -

1 an Important Component of Music Is the Rhythm, Or Duration of The

1 An important component of music is the rhythm, or duration of the sounds. We designate this with whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, etc., the names of which indicate the relative duration of notes (e.g., a half note lasts four times as long as an eighth note). ∼ 3 4 It isd of d courset t necessary to specify the actual (not just relative) duration of sounds. There are several ways to do this, we shall discuss two which reflect the manner in which music is displayed. Printed music groups notes into measures, and begins each line with a time signature which looks like a fraction, and specifies the number of notes in each measure. For example, the time signature 3/4 specifies that each measure contains three quarter notes (or six eighth notes, or a half note and a quarter note, or any collection of notes of equal total duration). (The above schematic is not divided into measures; a whole note would not fit within a measure in 3/4 time.) Indeed, you cannot tell from looking just at a measure whether the time signature is 3/4 or 6/8, but both the top and bottom of the time signature are important for specifying the nature of the rhythm. The top number specifies how many beats (or fundamental time units) there are in a measure, and the bottom number specifies which note represents the fundamental time unit. For example, 3/4 time specifies three beats to a measure with a quarter note representing one beat, 6/8 time specifies six beats to a measure with an eighth note representing one beat. -

Jumpin' Punkins by Mercer Ellington Arranged by Duke Ellington Unit 1

Jumpin’ Punkins By Mercer Ellington Arranged by Duke Ellington Unit 1: Composer Mercer Ellington was born in Washington D.C., on March 11, 1919. He was the son of world famous composer, pianist, and bandleader, Duke Ellington. He tried for his entire life to escape from under the shadow of his famous father. A talented trumpet player, Mercer studied music with his father and wrote his first composition, “Pigeons and Peppers”, at the age of eighteen. Mercer, a classically trained musician, studied music in New York at Columbia University and the Institute of Musical Arts at Juilliard. He had several professions in life including salesman, disk jockey, record company executive, trumpet player, and aide to his father. Mercer performed in Sy Oliver’s Band after WWII, led his own band for a number of years, and then served as music director for Della Reese in 1960. He took over as leader of the Ellington Orchestra after his father’s death in 1974. He even won a Grammy with the Ellington Orchestra in 1988 for “Digital Duke.” This recording actually pulled together many of the former greats of the Ellington Orchestra including Clark Terry, Norris Turney and special guest artists including Branford Marsalis and Sir Roland Hanna. Mercer also wrote a biography of his father entitled “Duke Ellington in Person,” offering a personal account of Duke Ellington from a son’s perspective. Unit 2: Composition Mercer wrote Jumpin’ Punkins (1941) after being asked by his father, Duke, to join the band as a writer. It is believed that even though Mercer composed several compositions during this two-year period, Duke actually arranged this chart for the Ellington Orchestra himself. -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development

THE SAXOPHONE IN CHINA: HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE AND DEVELOPMENT Jason Pockrus Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Eric M. Nestler, Major Professor Catherine Ragland, Committee Member John C. Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pockrus, Jason. The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 222 pp., 12 figures, 1 appendix, bibliography, 419 titles. The purpose of this document is to chronicle and describe the historical developments of saxophone performance in mainland China. Arguing against other published research, this document presents proof of the uninterrupted, large-scale use of the saxophone from its first introduction into Shanghai’s nineteenth century amateur musical societies, continuously through to present day. In order to better describe the performance scene for saxophonists in China, each chapter presents historical and political context. Also described in this document is the changing importance of the saxophone in China’s musical development and musical culture since its introduction in the nineteenth century. The nature of the saxophone as a symbol of modernity, western ideologies, political duality, progress, and freedom and the effects of those realities in the lives of musicians and audiences in China are briefly discussed in each chapter. These topics are included to contribute to a better, more thorough understanding of the performance history of saxophonists, both native and foreign, in China. -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement. -

Brevard Live January 2018

Brevard Live January 2018 - 1 2 - Brevard Live January 2018 Brevard Live January 2018 - 3 4 - Brevard Live January 2018 Brevard Live January 2018 - 5 6 - Brevard Live January 2018 Contents January 2018 FEATURES FRANK RIOS SISTER ACT The Rios Rock Band rose from the orig- Columns inal music of Frank Rios and his wish Sister Act is a musical based on the hit to perform it. Four years later the band Charles Van Riper 1992 film of the same name. This month plays, mostly covers, on the best stages Political Satire you can experience this hilarious musical 22 around. Brevard Live met up with Frank New Year’s Revolution on the main stage of the Henegar Center Rios to talk about music and life. in downtown Melbourne. Page 16 Calendars Page 11 25 Live Entertainment, Concerts, Festivals TITUSVILLE MARDI GRAS SELWYN BIRCHWOOD Sand Point Park in Titusville will trans- Lou’s Blues and promoter and local con- Show-Friends? form into a New Orleans style French cert-guru Mike Elko have joined forces 30 By Matt Bretz Quarter during the Titusville Mardi Gras to put a series of national Blues shows Party & Parade, set for Saturday, Febru- together held on Sunday evening, “once Monkeys? a month,” says Elko. To start off the se- ary 10th, 2018. In Florida? ries, they feature one of Florida’s best 33 Page 15 by Matt Bretz kept secret - Selwyn Birchwood. SEAFOOD & MUSIC FESTIVAL Page 18 Flori-duh! This year organizers have gone all out to by Charles Knight offer music fans an incredible line-up of BYRON CUEVAS 36 live entertainment.