Owens, Jimmy Interview 2 Owens, Jimmy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

WSO Holidays Newslet

The content in this preview is based on the last saved version of your email - any changes made to your email that have not been saved will not be shown in this preview. Williamsport Symphony Orchestra Newsletter November 2013 2013-2014 Calendar Conductor's Corner 24 Billtown Brass Holiday Concert Community Arts Center 7:00 pm Dear Friends, December 2013 Our October concert was a great 02 Meet the Maestro start for the season! The Capitol Lounge of CAC orchestra played beautifully, we 5:30 -7 pm had a first rate guest artist and a 03 WSO Time to Rejoice! very enthusiastic audience. I am Community Arts Center very proud of our musicians and 7:30 pm can't wait for the next concerts. February 2014 As the holidays are approaching, 10 Meet the Maestro a different type of music is ringing in my ears. From Capitol Lounge of CAC 5:30 -7 pm festive to solemn, entertaining to profound, it's definitely music for everyone. I was lucky to be in Dublin several 11 WSO Fantastic Tales years ago and visit the church where Handel's Messiah was Community Arts Center 7:30 pm premiered in 1742. I was moved to be in that place. Although it took one year until it was performed in London 23 Close Up Concert # 2 and other places, this piece become a staple of the holiday Mary Lindsay Welch Honors Hall, Lycoming season and one of the most performed oratorios of all College time. We have chosen selections from it including the 3:00 pm famous "Hallelujah" chorus accompanied by the wonderful 23 Williamsport Symphony Williamsport High School Choir and four excellent soloists Youth Orchestra (WSYO) from the area. -

Seconded By~+--~· \ Gq '

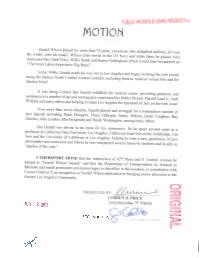

PUBUC WORKS &GANG REDUCTiO. -. MOTION Gerald Wilson played for more than 75 years, a musician who delighted millions, all over the world, with his music. Wilson later served in the US Navy and while there he played with musicians like Clark Terry, Willie Smith and Jimmy Nottingham which would later be reunited as "The Great Lakes Experience Big Band." In the 1940s, Gerald made his way out to Los Angeles and began working the club circuit along the famous South Central Avenue corridor, including famous musical venues like and the Dunbar Hotel. It was along Central that Gerald solidified his musical career, providing guidance and assistance to a number of up and coming jazz musicians like Bobby Bryant, Harold Land Jr., Jack Wilkins and many others and helping to make Los Angeles the epicenter of Jazz on the west coast. Over more than seven decades, Gerald played and arranged for a tremendous number of jazz legends including Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Nancy Wilson, Sarah Vaughan, Ray Charles, Julie London, Ella Fitzgerald and Dinah Washington, among many others. But Gerald was driven to do more for his community. So he spent several years as a professor at California State University Los Angeles, California State University Northridge, Cal Arts and the University of California at Los Angeles, helping to train a new generation of jazz aficionados and musicians and where he was recognized several times by students and faculty as "teacher ofthe year." I THEREFORE MOVE that the intersection of 42nd Place and S. Central Avenue be named as "Gerald Wilson Square" and that the Department of Transportation be directed to fabricate and install permanent ceremonial signs to this effect at this location, in consultation with Council District 9, in recognition of Gerald Wilson dedication to bringing music education to the Greater Los Angeles Community. -

Richard Marx Josh Turner Black Violin Chris White Tim Coffman Parsons

Tim Coffman Black Violin Photo Credit: Colin Brennan Josh Turner Richard Marx Photo Credit: Lois Greenfield Parsons Dance Chris White welcome to North Central College t’s time for another great season in the arts at ticket holder who said she was very happy to pick North Central College here in Naperville! We her own shows and didn’t have to give the tickets I are so excited to bring you another wonderful away to the shows when she was out of town. This season full of the best artists in the business. I is JUST what we were hoping would happen. suppose I could say sit back, relax and enjoy the I also want to thank our Friends of the Arts, the show, but in a way the only time we want you to sit angels who donate to the fine arts above and beyond back and relax is just before the show starts. We have the price of the tickets, and our corporate, hotel and such a terrific lineup this season that the excitement restaurant sponsors. You are making a difference will make it impossible to relax. So how about if I in our community. You understand how important say relax, save your energy because you are going the arts are to all of us and how they impact our to need it for the thunderous applause that you’re community. bound to give for whichever performer you came to see. Patrons come to our shows, they eat in Naperville restaurant, and stay in Naperville hotels. So, thank From Josh Turner to Richard Marx, Black Violin you for all you do, from the largest corporation to to Parsons Dance, Andy Williams Christmas the single donor. -

Powell, His Trombone Student Bradley Cooper, Weeks

Interview with Benny Powell By Todd Bryant Weeks Present: Powell, his trombone student Bradley Cooper, Weeks TBW: Today is August the 6th, 2009, believe it or not, and I’m interviewing Mr. Benny Powell. We’re at his apartment in Manhattan, on 55th Street on the West Side of Manhattan. I feel honored to be here. Thanks very much for inviting me into your home. BP: Thank you. TBW: How long have you been here, in this location? BP: Over forty years. Or more, actually. This is such a nice location. I’ve lived in other places—I was in California for about ten years, but I’ve always kept this place because it’s so centrally located. Of course, when I was doing Broadway, it was great, because I can practically stumble from my house to Broadway, and a lot of times it came in handy when there were snow storms and things, when other musicians had to come in from Long Island or New Jersey, and I could be on call. It really worked very well for me in those days. TBW: You played Broadway for many years, is that right? BP: Yeah. TBW: Starting when? BP: I left Count Basie in 1963, and I started doing Broadway about 1964. TBW: At that time Broadway was not, nor is it now, particularly integrated. I think you and Joe Wilder were among the first to integrate Broadway. BP: It’s funny how it’s turned around. When I began in the early 1960s, there were very few black musicians on Broadway, then in about 1970, when I went to California, it was beginning to get more integrated. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Concert Jazz Orchestra

PERSONNEL STUDIO JAZZ BAND CONCERT JAZZ ORCHESTRA Alto Sax—Hayden Dekker* Alto Sax—Kyle Myers*† Alto Sax—Jordan Guzman* Alto Sax—Grant Beach* Tenor Sax—Andrew Rosenblum* Tenor Sax—Brandon Baker* Tenor Sax—Brandon Muhawi* Tenor Sax—Josias Miguel* Baritone Sax—Emily Williams* Baritone Sax—Howard Hardaway* Trumpet—Max Maynard Trumpet—Andrew Solares*+ Trumpet—Elias Rodriguez* Trumpet—Adam Portocarrero*+ Trumpet—Ryan Furness* Trumpet—Evan Hamada*> Trumpet—Alex Hille Trumpet—Adam Rosenblum* CONCERT JAZZ Trombone—Ethan Saxe Trombone—Ethan Saxe Trombone—Luke Lizotte* Trombone—Chris Innes+ Trombone—Max Mineer* Trombone—Anna Menotti* Trombone—Daniel Nakazono Trombone—Rob Verdugo Trombone—Evan Wicks Guitar—Mauricio Martin* ORCHESTRA Vibes—Joseph Nazariego* Guitar—Daniel Mandrychenko* Piano—Eric Bell*^ Piano—Alex Flavell*^ Bass—Matthew Evans* Bass—Evan Tom*‡ Drums—Jackie Rush*^ / Ryan Dong* Drums—Karo Galadjian*^ *—Jazz Studies Major †—Beau & Jo France Graduate Jazz Studies Scholar STUDIO JAZZ BAND +—Cole Scholar ‡—Jazz Studies Scholar ^—KKJZ Scholar >—President's Scholar JEFF JARVIS, DIRECTOR UPCOMING “JAZZ AT THE BEACH” EVENTS JEFF HAMILTON, GUEST ARTIST November 23 Pacific Standard Time, Jazz & Tonic November 24 Jazz Lab Band, 4PM, Daniel Recital Hall December 6 Jazz @ the Nugget, 5PM SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2019 4:00PM GERALD R. DANIEL RECITAL HALL PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. This concert is funded in part by the INSTRUCTIONALLY RELATED ACTIVITIES FUNDS (IRA) provided by California State University, Long Beach. recordings for such names as Lou Rawls, Michael Jackson, Melba Moore, The O’Jays and more. Live performance credits include Gladys Knight, Van Morrison, Dizzy Gillespie, Louie Bellson, Joe Williams, Benny Golson, Jon Hendricks, Jimmy Heath, Joe Lovano, Henry Mancini, Slide Hampton, Kevin Mahogany, Grady Tate, Eddie Daniels, Rob McConnell, and Doc Severinsen. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

American Music Review the H

American Music Review The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XLII, Number 2 Spring 2013 Invisible Woman: Vi Redd’s Contributions as a Jazz Saxophonist By Yoko Suzuki, University of Pittsburgh The story of alto saxophonist Vi Redd illustrates yet another way in which women jazz instrumentalists have been excluded from the dominant discourse on jazz history. Although she performed with such jazz greats as Count Basie, Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie, and Earl Hines, she is rarely discussed in jazz history books except for those focusing specifically on female jazz musicians. One reason for her omission is that jazz historiography has heavily relied on commercially produced recordings. Despite her active and successful career in the 1960s, Redd released only two recordings as a bandleader, in 1962 and 1964. Reviews of these recordings, along with published accounts of her live performances and memories of her fellow musicians illuminate how Redd’s career as a jazz instrumentalist was greatly shaped by the established gender norms of the jazz world. Elvira “Vi” Redd was born in Los Angeles in 1928. Her father, New Orleans drummer Alton Redd, worked with such jazz greats as Kid Ory, Dexter Gordon, and Wardell Gray. Redd began singing in church when she was five, and started on alto saxophone around the age of twelve, when her great aunt gave her a horn and taught her how to play. Around 1948 she formed a band with her first husband, trumpeter Nathaniel Meeks. She played the saxophone and sang, and began performing professionally. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JON HENDRICKS NEA Jazz Master (1993) Interviewee: Jon Hendricks (September 16, 1921 - ) and, on August 18, his wife Judith Interviewer: James Zimmerman with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 17-18, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 95 pp. Zimmerman: Today is August 17th. We’re in Washington, D.C., at the National Portrait Galley. Today we’re interviewing Mr. Jon Hendricks, composer, lyricist, playwright, singer: the poet laureate of jazz. Jon. Hendricks: Yes. Zimmerman: Would you give us your full name, the birth place, and share with us your familial history. Hendricks: My name is John – J-o-h-n – Carl Hendricks. I was born September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, the ninth child and the seventh son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. My father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the AME Church. Zimmerman: Who were your brothers and sisters? Hendricks: My brothers and sisters chronologically: Norman Stanley was the oldest. We call him Stanley. William Brooks, WB, was next. My sister, the oldest girl, Florence Hendricks – Florence Missouri Hendricks – whom we called Zuttie, for reasons I never For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 really found out – was next. Then Charles Lancel Hendricks, who is surviving, came next. Stuart Devon Hendricks was next. Then my second sister, Vivian Christina Hendricks, was next. Then Edward Alan Hendricks came next. -

1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993

dF Universitycrldaho LIoNEL HmPToN/CHEVRoN JnzzFrsrr\Al 1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993 t./¡ /ìl DR. LYNN J. SKtNNER, Jazz Festival Executive Director VtcKt KtNc, Program Coordinator BRTNoR CAtN, Program Coordinator J ¡i SusnN EHRSTINE, Assistant Coordinator ltl ñ 2 o o = Concert Producer: I É Lionel Hampton, J F assisted by Bill Titone and Dr. Lynn J. Skinner tr t_9!Ð3 ü This project is supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts We Dedicate this 1993 Lionel Hømpton/Chevron Jøzz Festivül to Lionel's 65 Years of Devotion to the World of Juzz Page 2 6 9 ll t3 r3 t4 l3 37 Collcgc/Univcrsity Compctition Schcdulc - Thursday, Feh. 25, 1993 43 Vocal Enserrrbles & Vocal Conrbos................ Harnpton Music Bldg. Recital Hall ...................... 44 45 46 47 Vocal Compctition Schcrlulc - Fridav, Fcli. 2ó, 1993 AA"AA/AA/Middle School Ensenrbles ..... Adrrrin. Auditoriunr 5l Idaho Is OurTenitory. 52 Horizon Air has more flights to more Northwest cities A/Jr. High/.Ir. Secondary Ensenrbles ........ Hampton Music Blclg. Recital Hall ...............,...... 53 than any other airline. 54 From our Boise hub, we serve the Idaho cities of Sun 55 56 Valley, Idaho Falls, Lewiston, MoscowÆullman, Pocatello and AA/A/B/JHS/MIDS/JR.SEC. Soloists ....... North Carnpus Cenrer ll ................. 57 Twin Falls. And there's frequent direct service to Portland, lnstrurncntal Corupctilion'Schcrlulc - Saturday, Fcll. 27, 1993 Salt Lake City, Spokane and Seattle as well. We also offer 6l low-cost Sun Valley winter 8,{. {ÀtûåRY 62 and summer vacation vt('8a*" å.t. 63 packages, including fOFT 64 airfare and lodging. -

Sammy Figueroa Full

Sammy Figueroa has long been regarded as one of the world’s great musicians. As a much-admired percussionist he provided the rhythmical framework for hundreds of hits and countless recordings. Well-known for his versatility and professionalism, he is equally comfortable in a multitude of styles, from R & B to rock to pop to electronic to bebop to Latin to Brazilian to New Age. But Sammy is much more than a mere accompanist: when Sammy plays percussion he tells a story, taking the listener on a journey, and amazing audiences with both his flamboyant technique and his subtle nuance and phrasing. Sammy Figueroa is now considered to be the most likely candidate to inherit the mantles of Mongo Santamaria and Ray Barretto as one of the world’s great congueros. Sammy Figueroa was born in the Bronx, New York, the son of the well-known romantic singer Charlie Figueroa. His first professional experience came at the age of 18, while attending the University of Puerto Rico, with the band of bassist Bobby Valentin. During this time he co-founded the innovative Brazilian/Latin group Raices, which broke ground for many of today’s fusion bands. Raices was signed to a contract with Atlantic Records and Sammy returned to New York, where he was discovered by the great flautist Herbie Mann. Sammy immediately became one of the music world’s hottest players and within a year he had appeared with John McLaughlin, the Brecker Brothers and many of the world’s most famous pop artists. Since then, in a career spanning over thirty years, Sammy has played with a