Nutr/Epid 813: Nutritional Epidemiology, Spring 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition — Ph.D. 1

Nutrition — Ph.D. 1 NUTRITION — PH.D. Prerequisites • Master's degree in nutrition preferred; or an M.S. or M.P.H. degree Program director with completion of all prerequisite courses; or a health professional Sujatha Rajaram degree at the master's level or higher (M.D. or equivalent) • Advanced biochemistry (may be taken concurrently with the program) The Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree in nutrition prepares students to • Anatomy and physiology, microbiology, general chemistry, and effectively conduct nutrition research as well as apply nutritional science organic chemistry knowledge and appropriate research methods to address public health problems. The program provide's an advanced curriculum in nutrition, • G.P.A. of 3.5 or higher preferred th professional skills, and competencies required to support careers in • GRE or equivalent (above the 40 percentile in each section is teaching and research. This program is uniquely situated in the School favorable) of Public Health at a health sciences university. The program engages in interdisciplinary research, encouraging collaboration across public Individuals who may benefit from the health disciplines and the basic sciences, promoting and building upon its core legacy of vegetarian and plant-based nutrition. Areas of curricular program strength and research emphasis include plant-based diets and the health Individuals seeking careers in: of the individual, populations and the planet, nutritional epidemiology, diet • Academia (teaching and research) and chronic disease-risk reduction, and community nutrition. • Researcher in private industry, governmental agencies, nonprofit Students enrolled in this program are able to concurrently complete organizations, or research institutes coursework and practice experience necessary to sit for the registered • Public health nutritionist dietitian nutritionist (RDN) exam if not already an RDN. -

The Practice of Epidemiology

The Practice of Epidemiology A Meta-Regression Method for Studying Etiologic Heterogeneity across Disease Subtypes Classified by Multiple Biomarkers Molin Wang, Aya Kuchiba, Shuji Ogino Correspondence to Molin Wang, Departments of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 677 Huntington Ave., Boston, Massachusetts (email: [email protected]) Abbreviations: CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; MPE, molecular pathological epidemiology; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; NHS, the Nurses’ Health Study; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; RRR, ratio of relative risk. We use standardized official symbol BRAF, which is described at www.genenames.org. Word count main abstract: 200 Word count text: 3615 N.Figures: 0 N.Tables: 2 Appendices: 0 1 Abstract In interdisciplinary biomedical, epidemiological, and population research, it is increasingly necessary to consider pathogenesis and inherent heterogeneity of any given health condition and outcome. As the unique disease principle implies, no single biomarker can perfectly define disease subtypes. The complex nature of molecular pathology and biology necessitates biostatistical methodologies to simultaneously analyze multiple biomarkers and subtypes. To analyze and test for heterogeneity hypothesis across subtypes defined by multiple categorical and/or ordinal markers, the authors developed a meta-regression method that can utilize existing statistical software for mixed model analysis. This method can be used to assess whether the exposure- subtype associations are different across subtypes defined by one marker while controlling for other markers, and to evaluate whether the difference in exposure- subtype association across subtypes defined by one marker depends on any other markers. -

Encouraging Healthy Lifestyle Practices to Protect Health from Environmental Pollution

Encouraging Healthy Lifestyle Practices to Protect Health from Environmental Pollution Dawn Brewer, PhD, RD, LD July 26, 2019 NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP) Purpose: The NIEHS SRP supports research that provides practical, scientific solutions to protect health, the environment and communities. Source: https://tools.niehs.nih.gov/srp/sites/www.cfm University of Kentucky Superfund Research Center (UK-SRC): Nutrition and Superfund Chemical Toxicity Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) Cl Cl Cl Cl Cl Exposure Cardiovascular diseases Diabetes Obesity Cancer Oxidative Suppression of the immune system damage Dysfunction of reproductive and nervous systems Source: Sci Total Environ. 2009 Dec 1; 407(24): 6109-6119 Source: http://www.epa.gov/opptintr/pcb/ Kentucky Contains Hundreds of Hazardous Waste Sites and Contaminated Waterways • 13 National Priority List sites • 248 state superfund sites • 465 sites pending review • Fish consumption advisories for PCBs exist for Kentucky streams and the entire Ohio River that forms the northern border Source: https://www.kyforward.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Kentucky- Waterways-map.jpg Kentucky Experiences Poor Health Outcomes United Health Indicator Kentucky States Ranking Diabetes (%) 12.9 10.5 44 Heart disease (%) 6.2 3.9 49 Cancer deaths (per 100,000 population) 234.9 189.8 50 High blood pressure (%) 39.4 32.2 46 Obesity (%) 34.3 31.3 43 Source: America's Health Rankings analysis of CDC WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death, Multiple Cause of Death files, United Health Foundation, AmericasHealthRankings.org, Accessed 2019. Kentuckians Face Increased Vulnerability to Environmental Pollution • A growing and convincing body of research (including results from UK-SRC) indicates that nutrition may function as a modulator of vulnerability to environmental insults with nutrition serving to both better or worsen the health impacts associated with exposure to environmental toxins. -

Master of Public Health/Master of Science in Nutrition Dual Degree Proposal (Plan B, Non-Thesis Requiring) Document of December

Master of Public Health/Master of Science in Nutrition Dual Degree Proposal (Plan B, non-thesis requiring) Document of December 8, 2014; Revised February 2, 2015 This is a dual degree program that is offered jointly by the Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, and Nutrition. The core Master Degree courses include a mixture of those from nutrition, biochemistry and public health. 1. Background and Justification The World Health Organization, (WHO), identifies diet and nutrition as a lifestyle factor critical for maintenance of health and well-being, as well as a factor influencing risk of chronic disease. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and obesity are examples of chronic diseases significantly related to diet and nutrition. Obesity is one of the most common conditions and is growing to epidemic proportions. The two most common associated co-morbidities of obesity, type 2 diabetes and hypertension, are highly prevalent health risks and are among the principal causes of death in the general population. Additionally, in third world countries, malnutrition is a very common cause of infection or death, especially in young children. Accordingly, knowledge of the basic elements of good nutrition and the biochemical pathways associated with the metabolism of protein, fat and carbohydrate offers important contributions to mitigate these health problems. The proposed dual degree program will provide the student with a core understanding of the mechanics of metabolism combined with advanced courses in public health and nutrition. This combined approach will yield a highly qualified and competitive public health practitioner trained to develop evidence based policy, programs, strategies and advocacy to address these health risks and problems. -

Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition

P000i-00xx 3/12/05 8:54 PM Page i Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition Second edition VITPR 3/12/05 16:50 Page ii WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements (1998 : Bangkok, Thailand). Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition : report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation, Bangkok, Thailand, 21–30 September 1998. 1.Vitamins — standards 2.Micronutrients — standards 3.Trace elements — standards 4.Deficiency diseases — diet therapy 5.Nutritional requirements I.Title. ISBN 92 4 154612 3 (LC/NLM Classification: QU 145) © World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2004 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Market- ing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permis- sion to reproduce or translate WHO publications — whether for sale or for noncommercial distri- bution — should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]), or to Chief, Publishing and Multimedia Service, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 00100 Rome, Italy. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Structured Measurement Error in Nutritional Epidemiology 3 � 1 = F 60 Ki2 J Kij

JASA jasa v.2004/12/09 Prn:26/10/2006; 10:42 F:jasaap05194r.tex; (Diana) p. 1 Structured Measurement Error in Nutritional 1 Epidemiology: Applications in the Pregnancy, 60 2 61 3 Infection, and Nutrition (PIN) Study 62 4 63 5 Brent A. JOHNSON,AmyH.HERRING, Joseph G. IBRAHIM, and Anna Maria SIEGA-RIZ 64 6 65 7 66 8 Preterm birth, defined as delivery before 37 completed weeks’ gestation, is a leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality. Identifying 67 factors related to preterm delivery is an important goal of public health professionals who wish to identify etiologic pathways to target 9 68 for prevention. Validation studies are often conducted in nutritional epidemiology in order to study measurement error in instruments that 10 are generally less invasive or less expensive than “gold standard” instruments. Data from such studies are then used in adjusting estimates 69 11 based on the full study sample. However, measurement error in nutritional epidemiology has recently been shown to be complicated 70 12 by correlated error structures in the study-wide and validation instruments. Investigators of a study of preterm birth and dietary intake 71 13 designed a validation study to assess measurement error in a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) administered during pregnancy and with 72 the secondary goal of assessing whether a single administration of the FFQ could be used to describe intake over the relatively short 14 73 pregnancy period, in which energy intake typically increases. Here, we describe a likelihood-based method via Markov chain Monte Carlo 15 to estimate the regression coefficients in a generalized linear model relating preterm birth to covariates, where one of the covariates is 74 16 measured with error and the multivariate measurement error model has correlated errors among contemporaneous instruments (i.e., FFQs, 75 17 24-hour recalls, and biomarkers). -

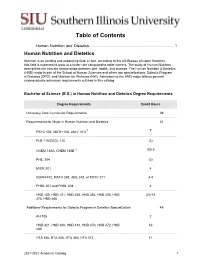

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Human Nutrition and Dietetics.............................................................................. 1 Human Nutrition and Dietetics Nutrition is an exciting and expanding field. In fact, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, this field is expected to grow at a faster rate compared to other careers. The study of Human Nutrition exemplifies the intricate relationships between diet, health, and disease. The Human Nutrition & Dietetics (HND) major is part of the School of Human Sciences and offers two specializations: Didactic Program in Dietetics (DPD); and Nutrition for Wellness (NW). Admission to the HND major follows general undergraduate admission requirements outlined in this catalog. Bachelor of Science (B.S.) in Human Nutrition and Dietetics Degree Requirements Degree Requirements Credit Hours University Core Curriculum Requirements 39 Requirements for Major in Human Nutrition and Dietetics 32 PSYC 102, MATH 108, UNIV 101I 1 7 PLB 115/ZOOL 115 (3) CHEM 140A, CHEM 140B 2 (3)+5 PHIL 104 (3) MICR 201 4 QUAN 402, MATH 282, ABE 318, or PSYC 211 3-4 PHSL 201 and PHSL 208 4 HND 100, HND 101, HND 320, HND 356, HND 425, HND (2)+16 475, HND 485 Additional Requirements for Didactic Program in Dietetics Specialization 49 AH 105 2 HND 321, HND 400, HND 410, HND 470, HND 472, HND 16 480 HTA 156, HTA 206, HTA 360, HTA 373 11 2021-2022 Academic Catalog 1 Degree Requirements Credit Hours MKTG 304 3 PSYC 323 3 Electives 11 Additional Requirements for Nutrition for Wellness Specialization 49 AH 105 2 KIN 201 3 HTA 206 (1) HED 311, HED 312 6 HND 321, HND 410, HND 445, HND 495 12 Approved Electives 25 Total 120 1 The numbers in parentheses are counted as part of the 39-hour University Core Curriculum. -

Food and Nutrition Security and Environmental Pollution: Taboo and Stigma

DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232017222.10582016 527 Segurança alimentar e nutricional e contaminação ambiental: ARTICLE ARTIGO tabu e estigma Food and nutrition security and environmental pollution: taboo and stigma Mércia Ferreira Barreto 1 Maria do Carmo Soares de Freitas 1 Abstract This qualitative approach study seeks to Resumo Este estudo de abordagem qualitati- understand the meanings of Food and Nutrition va busca compreender significados de Segurança Security (FNS) and environmental contamination Alimentar e Nutricional (SAN) e contaminação by shellfish gatherers in the municipality of Santo ambiental por marisqueiras do município de San- Amaro, Bahia. Solid and industrial waste (mainly to Amaro, Bahia. Resíduos sólidos e industriais lead) and biological waste are released in the Sub- (principalmente Chumbo), e biológicos são lança- aé river and in the mangrove, compromising food dos no rio Subaé e no manguezal, comprometendo resources, life and health of the population. Shell- fontes alimentares, a vida e a saúde da popula- fish gatherers selling their mangrove-derived prod- ção. As marisqueiras, ao tentarem comercializar ucts are stigmatized by people of this municipality, os produtos do mangue, são estigmatizadas pela as well as other cities in the Recôncavo Baiano, população deste e outros municípios do Recôncavo and, as a result, do not reveal the origin of shellfish baiano e, por isso, silenciam sobre a origem dos sold in the market. Silence and contamination de- mariscos que vendem na feira. Compreende-se o nial are understood as ways to ensure the FNS, the silêncio e a negação da contaminação como for- naturalization of social inequality and in favor of mas de garantir a SAN, a naturalização da desi- survival. -

2. Genetically Modified Food Crops and Their Contribution to Human

Trends in Food Science & Technology 14 (2003) 191–209 2. Genetically modified food classical nutrient deficiencies, although over-consump- crops and their tion is a problem for some. Also in relatively wealthy countries there is, in general, good access to affordable medical care to meet health needs and most consumers contribution to in rich countries have access to a relatively inexpensive supply of safe and healthy food. In these settings, the human nutrition possibility that biotechnology might reduce the price of food or make food more beneficial to health is a rela- tively minor concern. Rather, public debate about and food quality genetically modified foods (GMFs) appears to have focused on the potential for harm to either the environ- ment or health without a clear definition of benefit to the consumer. a The situation, of course, is quite different in poor Howarth E. Bouis *, Bruce countries where malnutrition and ill health are frequent. M. Chassyb and James Poor consumers typically spend 70% of their incomes c on food, and diets consist primarily of staple foods, O. Ochanda which lack the vitamins, minerals and, very likely, other food components necessary to sustain good health and minimise the risk of adult onset diet-related chronic diseases. In addition, low incomes typically preclude the poor from access to adequate health care. aInternational Food Policy Research Institute, 2033 K There are three broad ways that biotechnology may Street, NW, Washington DC 20006 USA (fax: +1-202- benefit consumers in developing countries. First, bio- 467-4439; e-mail: [email protected]) technology offers a powerful, new tool to improve crop bBiotechnology Center, University of Illinois at productivity, both by making conventional breeding Urbana-Champaign, 238 NSRC, 1101 West Peabody faster and more efficient and, more controversially, by Drive, Urbana, IL 61801, USA the insertion of novel genes in a crop species, by use of cDeparment of Biochemistry, College of Biological & transgenic methods. -

Bioactive Nutrients and Nutrigenomics in Age-Related Diseases

molecules Review Bioactive Nutrients and Nutrigenomics in Age-Related Diseases Tania Rescigno 1, Luigina Micolucci 2,3, Mario F. Tecce 1 and Anna Capasso 1,* 1 Department of Pharmacy, University of Salerno, Fisciano 84084, Italy; [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (M.F.T.) 2 Computational Pathology Unit, Department of Clinical and Molecular Sciences, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona 60120, Italy; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Experimental Pathology, Department of Clinical and Molecular Sciences, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona 60120, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-089-989744 Academic Editor: Philippe Bulet Received: 18 November 2016; Accepted: 3 January 2017; Published: 8 January 2017 Abstract: The increased life expectancy and the expansion of the elderly population are stimulating research into aging. Aging may be viewed as a multifactorial process that results from the interaction of genetic and environmental factors, which include lifestyle. Human molecular processes are influenced by physiological pathways as well as exogenous factors, which include the diet. Dietary components have substantive effects on metabolic health; for instance, bioactive molecules capable of selectively modulating specific metabolic pathways affect the development/progression of cardiovascular and neoplastic disease. As bioactive nutrients are increasingly identified, their clinical and molecular chemopreventive effects are being characterized and systematic analyses encompassing the “omics” technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics) are being conducted to explore their action. The evolving field of molecular pathological epidemiology has unique strength to investigate the effects of dietary and lifestyle exposure on clinical outcomes. The mounting body of knowledge regarding diet-related health status and disease risk is expected to lead in the near future to the development of improved diagnostic procedures and therapeutic strategies targeting processes relevant to nutrition. -

Statistics Options

Statistics Options The following are graduate level statistics courses appropriate for students in the Nutritional Sciences Graduate Program (NSGP): 1. Rutgers Department of Statistics and Biostatistics Graduate Program Courses (960) http://catalogs.rutgers.edu/generated/nb-grad_current/pg399.html is a link to the graduate catalog pages with descriptions of the statistics courses taught by the statistics department. Interpretation of Data I 16:960:586 INTERPRETATION OF DATA I (3) Modern methods of data analysis with an emphasis on statistical computing: univariate statistics, data visualization, robust statistics, nonlinear models, logistic regression, generalized linear models (GLM), and smooth regression (including GAM models). Expect to use statistical software packages, such as SAS (or SPSS) and Splus (or R) in data analysis. Prerequisite: Level IV statistics. NSPG Notes: Level IV statistics can be fulfilled by an advanced undergraduate statistics course at the 400 level; the instructor for the course must be contacted to convey information about completion of undergraduate statistics to obtain permission to register for the course. Corequisite: 16:960:563 16:960:563 Regression Analysis (3) Review of basic statistical theory and matrix algebra; general regression models; computer application to regression techniques; residual analysis; selection of regression models; response surface methodology; experimental design models; and analysis of covariance. Emphasis on applications. Prerequisite: Level IV statistics 16:960:590 DESIGN OF -

NUTR 305: NUTRITIONAL EPIDEMIOLOGY Fall 2016 Course

NUTR 305: NUTRITIONAL EPIDEMIOLOGY Fall 2016 Course Syllabus Time and location of the course: Tuesdays 1:30-3:00PM Fridays 8:45-10:15AM Location: Jaharis 155 (Except practicum #1: September 30th in Sacker 514 and practicum #2: October 14th in Jaharis 156) Instructor : Fang Fang Zhang, MD, PhD Assistant Professor, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy 150 Harrison Ave, Boston, MA 02111 Email : [email protected] | Phone : 617-636-3704 Teaching Assistants: Danielle Haslam, MA MS Ph.D. Candidate, Nutritional Epidemiology Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy Email : [email protected] Mengxi Du MS/MPH Candidate Tufts University School of Medicine Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy Email : [email protected] Office Hours: Email anytime to set up an appointment Tufts Graduate Credit: 1.0 Prerequisites for taking this course: Required prerequisites for this course are the following: 1) Introductory Human Nutrition (e.g., NUTR 201 or 202) 2) Introductory Epidemiology (e.g., NUTR 204 or MPH 201) 3) Biostatistics (e.g., NUTR 209/309 A&B or MPH 205) Course Description: This course is designed for graduate students who are interested in conducting or better interpreting epidemiological studies relating diet and nutritional status to disease and health. There is an increasing awareness that various aspects of diet and nutrition may be important contributing factors in chronic disease. There are many important problems, however, in the implementation and interpretation of these studies. The purpose of this course is to examine methodologies used in nutritional epidemiological studies, and to review the current state of knowledge regarding diet and other nutritional indicators as etiologic factors in disease.