Teresa of Avila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

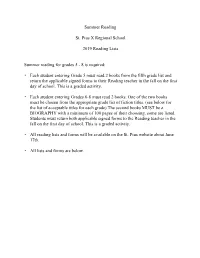

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer Reading for Grades 5

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer reading for grades 5 - 8 is required: ▪ Each student entering Grade 5 must read 2 books from the fifth grade list and return the applicable signed forms to their Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ Each student entering Grades 6-8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for each grade) The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. Students must return both applicable signed forms to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ All reading lists and forms will be available on the St. Pius website about June 17th. ▪ All lists and forms are below. ST. PIUS X - SUMMER READING Incoming Grade 8 (2019) 1. Each student entering Grade 8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for 8th grade) 2. The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. 3. Students must return the applicable signed forms (one form for the fiction title and one form for the biography title) to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. (both forms are below) 4. -

SJU Semester Abroad Policy

Saint Joseph's University Semester Abroad Policy Please be advised that starting with the fall 2003 semester, the following policy will be in effect for Saint Joseph’s University students who wish to study abroad and receive credit toward their Saint Joseph’s degree. Under this policy, students will remain registered at SJU and pay SJU full-time, day tuition plus a $100 Continuing Registration Fee for each semester they will be studying abroad. Students will be considered enrolled at Saint Joseph’s University while abroad and will be allowed to receive his/her entire financial aid package. Saint Joseph’s University will then pay the overseas program for the tuition portion of the program. Students will be responsible for all non-tuition fees associated with the program they will be attending. Please note that for some Saint Joseph’s University affiliated programs, students may be required to pay other fees to Saint Joseph’s University first and Saint Joseph’s University will then forward these fees to the program sponsor. Students must receive proper approval for their proposed program of study. Upon successful completion of an approved foreign program of study, credit will be granted towards graduation for all appropriate courses taken on SJU approved programs. APPLICATION PROCESS Students must apply through and receive approval from the Center for International Programs (CIP) in order to study abroad. The on-line application cycle for the fall term typically opens in January and closes in mid- February or on March 1st (depending on the program). The on-line application cycle for the spring term typically opens in late-August and closes in mid-September or on October 1st (again, depending on the program). -

How Mystics Hear the Song by W

20 Copyright © 2005 The Center for Christian Ethics How Mystics Hear the Song BY W. DENNIS TUCKER, JR. Mystics illustrate the power of the Song of Songs to shape our understanding of life with God. Can our lan- guishing love be transformed into radical eros—a deep yearning that knows only the language of intimate com- munion, the song of the Bridegroom and his Bride? he language of the Song of Songs—so replete with sexual imagery and not so subtle innuendos that it leaves modern readers struggling Twith the text’s value (much less its status as Scripture)—proved theo- logically rich for the patristic and medieval interpreters of the book. Rather than avoiding the difficult imagery present in the Song, they deemed it to be suggestive for a spiritual reading of the biblical text. In the Middle Ages, more “commentaries” were written on the Song of Songs than any other book in the Old Testament. Some thirty works were completed on the Song in the twelfth century alone.1 This tells us some- thing about the medieval method of exegesis. Following the lead of earlier interpreters, the medieval exegetes believed the Bible had spiritual mean- ing as well as a literal meaning. From this they developed a method of in- terpretation to uncover the “fourfold meaning of Scripture”: the literal, the allegorical, the moral, and the mystical.2 Medieval interpreters pressed be- yond the literal meaning to discover additional levels of meaning. A MONASTIC APPROACH Before we look at how three great mystics in the Christian tradition— Bernard of Clairvaux, Teresa of Avila, and John of the Cross—made use of the Song, let’s consider a larger issue: Why did the Song generate such per- sonally intense reflections in the works of the mystics? The form and focus of “monastic commentaries” in the medieval period was well suited for a spiritual reading of the Song. -

The Nous: a Globe of Faces1

THE NOUS: A GLOBE OF FACES1 Theodore Sabo, North-West University, South Africa ([email protected]) Abstract: Plotinus inherited the concept of the Nous from the Middle Platonists and ultimately Plato. It was for him both the Demiurge and the abode of the Forms, and his attempts at describing it, often through the use of arresting metaphors, betray substantial eloquence. None of these metaphors is more unusual than that of the globe of faces which is evoked in the sixth Ennead and which is found to possess a notable corollary in the prophet Ezekiel’s vision of the four living creatures. Plotinus’ metaphor reveals that, as in the case of Ezekiel, he was probably granted such a vision, and indeed his encounters with the Nous were not phenomena he considered lightly. Defining the Nous Plotinus’ Nous was a uniquely living entity of which there is a parallel in the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel. The concept of the Nous originated with Anaxagoras. 2 Although Empedocles’ Sphere was similarly a mind,3 Anaxagoras’ idea would win the day, and it would be lavished with much attention by the Middle and Neoplatonists. For Xenocrates the Nous was the supreme God, but for the Middle Platonists it was often the second hypostasis after the One.4 Plotinus, who likewise made the Nous his second hypostasis, equated it with the Demiurge of Plato’s Timaeus.5 He followed Antiochus of Ascalon rather than Plato in regarding it as not only the Demiurge but the Paradigm, the abode of the Forms.6 1 I would like to thank Mark Edwards, Eyjólfur Emilsson, and Svetla Slaveva-Griffin for their help with this article. -

Pain, Identity, and Emotional Communities in Nineteenth-Century English Convent Culture Carmen M

‘Why, would you have me live upon a gridiron?’: Pain, Identity, and Emotional Communities in Nineteenth-Century English Convent Culture Carmen M. Mangion I Introduction Polemicist and social critic Ivan Illich has outlined the importance of culture in furnishing means of experiencing, expressing, and understanding pain: ‘Precisely because culture provides a mode of organizing this experience, it provides an important condition for health care: it allows individuals to deal with their own pain.’1 The history of pain, approached through phenomenology (the lived experience of pain focused on subjectivity) and the various rhetorics of pain (narratives, rituals, symbols, etc.), can bring into sharp relief, as Illich has inferred, how pain is culturally derived and embedded in a society’s values and norms. Thus, the context of pain is critical as society and culture infuses it with a multiplicity of meanings. This essay explores nineteenth-century Catholic interpretations of pain, utilizing biography to examine how and why corporeal pain functioned as a means of both reinforcing Catholic beliefs in the utility of pain and of coping with pain. This does not necessarily imply that bodily pain was encouraged, enthusiastically welcomed, or self-inflicted. This article explores unwanted pain; not the self-inflicted pain of mortification or the violent pain of martyrdom that are often featured in medieval or early modern histories of pain. It will examine this unwanted pain in a defined space, the convent, and through a particular source, the biography of Margaret Hallahan (1803– 1868), founder of the Dominican Sisters of St Catherine of Siena, written by the future prioress, convert Augusta Theodosia Drane (1823–1894; in religion, Mother Francis Raphael) in 1869. -

![1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway Trans](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9268/1-aquinas-treatise-on-law-summa-theologiae-1272-2-1-9780895267054-gateway-trans-509268.webp)

1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway Trans

PROGRAM OF LIBERAL STUDIES JUNIOR READING LIST PLS 33101, SEMINAR III Students are asked to purchase the indicated editions. With Instructor’s permission other editions may be used. Students are expected to have done the first reading when coming to the first meeting of the seminar. 1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway trans. Parry, Questions 90-93 2 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae, Questions 94-97 3 Aquinas, On Faith, Summa Theologiae 2.2, trans. Jordan, 9780268015039 Notre Dame Prologue-Pt 2-2, Quest 1, 2, (Art 1-4, 10), 3, 4, (Art 3-5) 4 Aquinas, On Faith, Summa Theologiae, Questions 6, 10 5 Dante, The Inferno, The Divine Comedy [1321], 9780553213393 Bantam Cantos 1-17, trans. Mandelbaum 6 Dante, The Inferno, Cantos 18-34 7 Dante, Purgatorio, Cantos 1-18, trans. Mandelbaum 9780553213447 Bantam 8 Dante, Purgatorio, Cantos 19-33 9 Dante, Paradiso, Cantos 1-17, trans. Mandelbaum 9780553212044 Bantam 10 Dante, Paradiso, Cantos 18-33 11 Petrarch, "Ascent of Mount Ventoux" [1336] and "On His 9780226096049 Chicago Own Ignorance and That of Many Others" [1370], trans Nachod, in The Renaissance Philosophy of Man, ed. Cassirer, Kristeller, Randall 12 Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales [1387-1400], trans. Coghill, "Prologue," 9780140424386 Penguin "Knight’s Tale," "Millers Tale," and "Nun’s Priest Tale" (each tale with accompanying prologues and epilogues where appropriate) 13 Chaucer, Canterbury Tales, "Pardoner’s Tale," "Wife of Bath’s Tale," "The Clerk’s Tale," "Franklin’s Tale," and "Retraction" (each tale with accompanying prologues and epilogues where appropriate) 14 Julian of Norwich, Showings [1393], trans. -

Monasticism Old And

Study Guides for Monasticism Old and New These guides integrate Bible study, prayer, and worship to explore how monastic communities, classic and new, provide a powerful critique of mainstream culture and offer transforming possibilities Christian Reflection for our discipleship. Use them individually or in a series. You may A Series in Faith and Ethics reproduce them for personal or group use. A Vision So Old It Looks New 2 It is hard to be a Christian in America today. But that can be good news, the new monastics are discovering. If the cost of discipleship pushes us to go back and listen to Jesus again, it may open us to costly grace and the transformative power of resurrection life. In every era God has raised up new monas- tics to remind the Church of its true vocation. The Finkenwalde Project 4 Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s project at Finkenwalde Seminary to recover for congregations the deep Christian tradition is a prominent model for young twenty-first-century Christians. Weary of the false dichotomy between right belief and right practice, they seek the wholeness of discipleship in what Bonhoeffer called “a kind of new monasticism.” Evangelicals and Monastics 6 Could any two groups of Christians—evangelicals and monastics—be more different? But the New Monasticism movement has opened a new chapter in the relations of these previously estranged groups. Nothing is more characteristic of monastics and evangelicals than their unshakable belief that one cannot be truly spiritual without putting one’s faith into practice, and one cannot sustain Christian discipleship without a prayerful spirituality. -

Funk Soul Brother – Repertoire 2018

FUNK SOUL BROTHER – REPERTOIRE 2018 PARTY MUSIC & DANCE FLOOR FILLERS! A Little Less Conversation - Elvis Another One Bites The Dust - Queen Beat It - Michael Jackson Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Blame It On The Boogie - Jackson 5 Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Cake By The Ocean - DNCE Canned Heat - Jamiroquai Car Wash - Rose Royce Cold Sweat - James Brown Cosmic Girl - Jamiroquai Dance To The Music - Sly & The Family Stone Don't Stop Til You Get Enough - Michael Jackson Get Down On It - Kool and the Gang Get Down Saturday Night - Oliver Cheatham Get Lucky - Daft Punk Get Up Offa That Thing - James Brown Good Times - Chic Groove Is In The Heart - Dee-Lite Happy - Pharrell Williams Higher And Higher - Jackie Wilson I Believe in Mircales - Jackson Sisters I Wish - Stevie Wonder It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers Kiss - Prince Ladies Night - Kool and the Gang Lady Marmalade - Labelle Le Freak - Chic Let's Stay Together - Al Green (continued) +44 (0)1572 335108 • [email protected] • www.pureartists.co.uk Long Train Running - Doobie Brothers Locked Out of Heaven - Bruno Mars Love Shack - B52s Mercy - The Third Degree/Duffy Move On Up - Curtis Mayfield Move Your Feet - Junior Senior Mr Big Stuff - Jean Knight Mustang Sally - Wilson Pickett Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag - James Brown Pick Up The Pieces - Average White Band Play That Funky Music - Wild Cherry Rather Be - Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynne Rehab - Amy Winehouse Respect - Aretha Franklin Signed Sealed Delivered - Stevie Wonder Sir Duke - Stevie Wonder Superstition - Stevie Wonder -

EKBERT of SCHÖNAU, Stimulus Amoris

EKBERT OF SCHÖNAU, Stimulus amoris; THOMAS A KEMPIS, Imitatio Christi; PS.- AUGUSTINE [PATRICK OF DUBLIN?], De triplici habitaculo In Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment Southern France (?), c. 1440-1480 i (paper) + 89 + i (paper) folios on parchment, modern foliation in pencil top outer corner, complete (collation, i-viii10 ix10 [-10, cancelled with no loss of text]), no catchwords or signatures, ruled in lead with single full-length bounding lines, (justification, 111-110 x 90-87 mm.), written below the top line in a southern gothic bookhand in two columns of thirty lines, majuscules within text touched with red, red rubrics, two- to five-line red initials, lower margin, f. 1, excised, inscription in red on last page erased, rodent damage to lower, outer margin, with some loss of text, ff. 4-17 (usually a few letters in the bottom five or six lines) and more extensive damage to ff. 76-77, ink flaking on some folios. Bound in vellum over thin pasteboard in the seventeenth or eighteenth century, title, “Gersonis,” and shelfmark, “2[?]3,”written on spine in ink, two holes front and back covers from ties (now missing), some damage to the parchment covering the spine, but overall in good condition. Dimensions 166 x 123 mm. The Imitation of Christ’s call to follow the life of Christ as told in the Gospels may explain why it is still widely read today; hundreds of surviving manuscript copies witness its popularity during the later Middle Ages. Here it is accompanied by two texts that reflect other sides of medieval religious life – the extreme devotion to the Passion and the Cross of Ekbert of Schönau’s Stimulus amoris, and speculation on heaven, hell, and earth, found in De triplici habitaculo. -

Kenosis and the Nature of the Persons in the Trinity

Kenosis and the nature of the Persons in the Trinity David T. Williams Department of Historical and Contextual Theology University of Fort Hare ALICE E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Kenosis and the nature of the Persons in the Trinity Philippians 2:7 describes the kenosis of Christ, that is Christ’s free choice to limit himself for the sake of human salvation. Although the idea of Christ’s kenosis as an explanation of the incarnation has generated considerable controversy and has largely been rejected in its original form, it is clear that in this process Christ did humble himself. This view is consistent with some contemporary perspectives on God’s self-limitation; in particular as this view provides a justification for human freedom of choice. As kenosis implies a freely chosen action of God, and not an inherent and temporary limitation, kenosis is consistent with an affirmation of God’s sovereignty. This view is particularly true if Christ’s kenosis is seen as a limitation of action and not of his attributes. Such an idea does not present problems concerning the doctrine of the Trinity, specifically regarding the relation between the economic and the immanent nature of the Trinity. The Trinitarian doctrine, on the contrary, indeed complements this idea – specifically the concept of perichoresis (the inter- relatedness among the Persons of the Triniy and the relation between the two natures of Christ). Opsomming Kenosis en die aard van die Persone in die Drie-eenheid Filippense 2:7 beskryf die kenosis van Christus – sy vrye keuse om homself te ontledig ter wille van die mens se verlossing. -

Mysticism and Mystical Experiences

1 Mysticism and Mystical Experiences The first issue is simply to identify what mysti cism is. The term derives from the Latin word “mysticus” and ultimately from the Greek “mustikos.”1 The Greek root muo“ ” means “to close or conceal” and hence “hidden.”2 The word came to mean “silent” or “secret,” i.e., doctrines and rituals that should not be revealed to the uninitiated. The adjec tive “mystical” entered the Christian lexicon in the second century when it was adapted by theolo- gians to refer, not to inexpressible experiences of God, but to the mystery of “the divine” in liturgical matters, such as the invisible God being present in sacraments and to the hidden meaning of scriptural passages, i.e., how Christ was actually being referred to in Old Testament passages ostensibly about other things. Thus, theologians spoke of mystical theology and the mystical meaning of the Bible. But at least after the third-century Egyptian theolo- gian Origen, “mystical” could also refer to a contemplative, direct appre- hension of God. The nouns “mystic” and “mysticism” were only invented in the seven teenth century when spirituality was becoming separated from general theology.3 In the modern era, mystical inter pretations of the Bible dropped away in favor of literal readings. At that time, modernity’s focus on the individual also arose. Religion began to become privatized in terms of the primacy of individuals, their beliefs, and their experiences rather than being seen in terms of rituals and institutions. “Religious experiences” also became a distinct category as scholars beginning in Germany tried, in light of science, to find a distinct experi ential element to religion. -

Active Hope - a Podcast Collaboration Episode 2 Transcript

Active Hope - A podcast collaboration Episode 2 Transcript Marc Bamuthi Joseph: My name is Marc Bamuthi Joseph. I am a poet, I'm a dad, I'm an educator. Kamilah Forbes: I am Kamilah Forbes. I am a storyteller, a director, a producer, a wife, a mother, a daughter, and the executive producer of the Apollo Theater. Paola Prestini: My name is Paola Prestini. I'm a composer, I'm a mother, a wife, and a collaborator. Marc Bamuthi Joseph: For the Kennedy Center. Paola Prestini: For National Sawdust. Kamilah Forbes: For the Apollo Theater. This is Active Hope. Marc Bamuthi Joseph: This is Active Hope. Paola Prestini: This Active Hope. Marc Bamuthi Joseph: Hey, hey, hey, hey, what's good family? Paola Prestini: Good afternoon. Hi. Kamilah Forbes: Hey. Marc Bamuthi Joseph: Hi. What an outstanding pleasure to be with you all again. We're here to not only take the energy of the last year but to metabolize it in some way towards healing. Kamilah Forbes: That's right. Marc Bamuthi Joseph: Thinking about art, creativity, and of course hope as an instrument of transcending. So that's actually what's on the agenda for today. All three of us use our bodies in order to leave it. Art is a means of getting free. That is if we assume that freedom is an outcome of the body, that freedom isn't something to be legislated. And if freedom can't be legislated, neither can art, right? Marc Bamuthi Joseph: But on the other hand, we live in a country of free bodies and also of incarcerated bodies.