Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Bay of Fundy Guide

VISITOR AND ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019–2020 BAYNova OF FUNDYScotia’s & ANNAPOLIS VALLEY TIDE TIMES pages 13–16 TWO STUNNING PROVINCES. ONE CONVENIENT CROSSING. Digby, NS – Saint John, NB Experience the phenomenal Bay of Fundy in comfort aboard mv Fundy Rose on a two-hour journey between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Ferries.ca Find Yourself on the Cliffs of Fundy TWO STUNNING PROVINCES. ONE CONVENIENT CROSSING. Digby, NS – Saint John, NB Isle Haute - Bay of Fundy Experience the phenomenal Bay of Fundy in comfort aboard mv Fundy Rose on a two-hour journey between Nova Scotia Take the scenic route and fi nd yourself surrounded by the and New Brunswick. natural beauty and rugged charm scattered along the Fundy Shore. Find yourself on the “Cliffs of Fundy” Cape D’or - Advocate Harbour Ferries.ca www.fundygeopark.ca www.facebook.com/fundygeopark Table of Contents Near Parrsboro General Information .................................. 7 Top 5 One-of-a-Kind Shopping ........... 33 Internet Access .................................... 7 Top 5 Heritage and Cultural Smoke-free Places ............................... 7 Attractions .................................34–35 Visitor Information Centres ................... 8 Tidally Awesome (Truro to Avondale) ....36–43 Important Numbers ............................. 8 Recommended Scenic Drive ............... 36 Map ............................................... 10–11 Top 5 Photo Opportunities ................. 37 Approximate Touring Distances Top Outdoor Activities ..................38–39 Along Scenic Route .........................10 -

Status of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar L.) Stocks in Rivers of Nova Scotia Flowing Into the Gulf of St

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2012/147 Document de recherche 2012/147 Gulf Region Région du Golfe Status of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar Etat des populations de saumon L.) stocks in rivers of Nova Scotia atlantique (Salmo salar) dans les rivières flowing into the Gulf of St. Lawrence de la Nouvelle-Ecosse qui déversent (SFA 18) dans le golfe du Saint-Laurent (ZPS 18) C. Breau Fisheries and Oceans Canada / Pêches et Océans Canada Gulf Fisheries Centre / Centre des Pêches du Golfe 343 University Avenue / 343 avenue de l’Université P.O. Box / C.P. 5030 Moncton, NB / N.-B. E1C 9B6 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et des in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle traite des the day in the time frames required and the problèmes courants selon les échéanciers dictés. documents it contains are not intended as Les documents qu’elle contient ne doivent pas être definitive statements on the subjects addressed considérés comme des énoncés définitifs sur les but rather as progress reports on ongoing sujets traités, mais plutôt comme des rapports investigations. d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans la language in which they are provided to the langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit envoyé au Secretariat. Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at Ce document est disponible sur l’Internet à www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs ISSN 1499-3848 (Printed / Imprimé) ISSN 1919-5044 (Online / En ligne) © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2013 © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT................................................................................................................................ -

Kelly River Wilderness Area

Barronsfield Eastern Habitat Joint Venture Lands Boss Pt. Maccan n Maccan Woods 242 KELLY RIVER i s 242 a Joggins Fossil Cliffs Strathcona An Overview of A New Candidate B River Hebert East Harrison Maccan River Wilderness Area Hardscrabble Lake Wildlife Management Area d Pt Joggins n River Hebert a 242 l Athol Station Cartography by the Protected Areas Branch of r Nova Scotia Environment, April 2011. e b Ragged Round 302 http://www.gov.ns.ca/nse/protectedareas/ m Reef Pt u Ragged Reef Meadow Bk Lake The information shown here was obtained C Athol courtesy of the NS Geomatics Centre (SNSMR) and the NS Department of Natural Resources. Ragged Pt k C © Crown Copyright, Province of Nova Scotia, n 2011. All rights reserved. o tt Two Rivers a This map is only a geographic representation. Christie Bk P Nova Scotia Environment and does not accept responsibility for any errors or omissions r contained herein. R e k rter B v Po South Athol i Haycock Bk i v y R k B e n e r rr a a r e B F l a t B k r v B k e l B v i i l ill i H h R d h n R L é a n n S o it r b t t Boars Back Ridge l p Lower e a S e 302 B m Pt h a Raven u r k lie Bearden s B th t d R Barrens oo ou o r rw n S Head ga r Shulie a B e Su E t Mitchell Bucktagen v K e l l y i c East c Meadows Barrens c Raven Head R Southampton Southampton e a r Chignecto Game Sanctuary Boundary M n 2 e k lm B g R i v e r E v R k to n iv e Tompkin Plains o S p r i i o o u m y r t h a B h R l k eir B w l h s C i F e r South e n v K Thundering i o 2 Brook R s LEGEND e Hill Bearden Bk n d i i n k Spar a l t ks S A Candidate Wilderness Areas (CWA) ch u B West ran k E B h Franklin Manor Brook Kelly River and Raven Head CWA S Forty Pettigrew I.R. -

Nova Scotia Inland Water Boundaries Item River, Stream Or Brook

SCHEDULE II 1. (Subsection 2(1)) Nova Scotia inland water boundaries Item River, Stream or Brook Boundary or Reference Point Annapolis County 1. Annapolis River The highway bridge on Queen Street in Bridgetown. 2. Moose River The Highway 1 bridge. Antigonish County 3. Monastery Brook The Highway 104 bridge. 4. Pomquet River The CN Railway bridge. 5. Rights River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. 6. South River The Highway 104 bridge. 7. Tracadie River The Highway 104 bridge. 8. West River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. Cape Breton County 9. Catalone River The highway bridge at Catalone. 10. Fifes Brook (Aconi Brook) The highway bridge at Mill Pond. 11. Gerratt Brook (Gerards Brook) The highway bridge at Victoria Bridge. 12. Mira River The Highway 1 bridge. 13. Six Mile Brook (Lorraine The first bridge upstream from Big Lorraine Harbour. Brook) 14. Sydney River The Sysco Dam at Sydney River. Colchester County 15. Bass River The highway bridge at Bass River. 16. Chiganois River The Highway 2 bridge. 17. Debert River The confluence of the Folly and Debert Rivers. 18. Economy River The highway bridge at Economy. 19. Folly River The confluence of the Debert and Folly Rivers. 20. French River The Highway 6 bridge. 21. Great Village River The aboiteau at the dyke. 22. North River The confluence of the Salmon and North Rivers. 23. Portapique River The highway bridge at Portapique. 24. Salmon River The confluence of the North and Salmon Rivers. 25. Stewiacke River The highway bridge at Stewiacke. 26. Waughs River The Highway 6 bridge. -

The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: B2 the Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos" J.H

GAC-MAC-CSPG-CSSS Pre-conference Field Trips A1 Contamination in the South Mountain Batholith and Port Mouton Pluton, southern Nova Scotia HALIFAX Building Bridges—across science, through time, around2005 the world D. Barrie Clarke and Saskia Erdmann A2 Salt tectonics and sedimentation in western Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia Ian Davison and Chris Jauer A3 Glaciation and landscapes of the Halifax region, Nova Scotia Ralph Stea and John Gosse A4 Structural geology and vein arrays of lode gold deposits, Meguma terrane, Nova Scotia Rick Horne A5 Facies heterogeneity in lacustrine basins: the transtensional Moncton Basin (Mississippian) and extensional Fundy Basin (Triassic-Jurassic), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia David Keighley and David E. Brown A6 Geological setting of intrusion-related gold mineralization in southwestern New Brunswick Kathleen Thorne, Malcolm McLeod, Les Fyffe, and David Lentz A7 The Triassic-Jurassic faunal and floral transition in the Fundy Basin, Nova Scotia Paul Olsen, Jessica Whiteside, and Tim Fedak Post-conference Field Trips B1 Accretion of peri-Gondwanan terranes, northern mainland Nova Scotia Field Trip B2 and southern New Brunswick Sandra Barr, Susan Johnson, Brendan Murphy, Georgia Pe-Piper, David Piper, and Chris White The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: B2 The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos" J.H. Calder, M.R. Gibling, and M.C. Rygel Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos” B3 Geology and volcanology of the Jurassic North Mountain Basalt, southern Nova Scotia Dan Kontak, Jarda Dostal, -

Cumberland County Births

RegisterNumber Type County AE Birthday Birthmonth Birthyear PAGE NUMBER Birthplace WHEREM LastName FirstName MiddleName ThirdName FatherFirstName MotherFirstName MotherLastName MarriedDay MarriedMonth MarriedYear TREE ID CODE 325 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 19 1 1866 16 229 TIDNISH NB ? JANE ROBERT JANE SPENCE 7 6 1851 605 2892 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 26 3 1872 170 212 WALLACE WALLACE ABBOT ANNIE LOUISA JOHN MARGT ELLEN CARTER 1870 605 3415 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 25 9 1873 201 331 WALLACE HALIFAX ABBOTT MAGGIE JOHN MAGGIE E CARTER 19 11 1871 605 4048 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 17 4 1875 238 148 SIX MILE ROAD HALIFAX ABBOTT JOHN GORDON JOHN MAGGIE E CARTER 18 11 1871 605 4050 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 17 4 1875 238 151 SIX MILE ROAD HALIFAX ABBOTT WILLIAM JOHN JOHN MAGGIE E CARTER 18 11 1871 605 2962 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 12 9 1872 173 291 SHINNIMICAS SHINNIMICAS ACKIN MARY L ROBERT SARAH ANGUS 13 9 1865 605 4022 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 9 6 1875 236 121 SHINNIMICAS SHINNIMICAS ACKIN SARAH A S ROBERT SARAH ANGUS 13 9 1865 605 110 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 11 6 1865 4 123 TIDNISH TIDNISH ACKLES GEORGE O H.J. ELIZA OXLEY 4 11 605 384 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 5 4 1865 19 293 CROSS ROADS NB ACKLES AVICE CHARLES RUTH ANDERSON 3 11 1844 605 541 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 7 7 1866 29 483 TIDNISH GREAT VILLAGE ACKLES JOHN M JOHN JANE ACKERSON 28 3 1865 605 1117 Births Cumberland Don Lewis 7 12 1867 62 110 NB ACKLES EMILY R JOHN H H.J. -

Sewage Management in the Gulf of Maine

Sewage Management in the Gulf of Maine WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS April 11-12, 2002 Patricia R. Hinch1, Sadie Bryon2, Kim Hughes3, Peter G. Wells4 1Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Labour, 2Bluenose Atlantic Coastal Action Program, 3New Brunswick Department of Environment and Local Government, 4Environmental Conservation Branch, Environment Canada Gulf of Maine Council Mission “To maintain and enhance environmental quality in the Gulf of Maine and to allow for sustainable resource use by existing and future generations.” i This is a publication of the Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment. For additional copies or information, please visit the Gulf of Maine Council website (www.gulfofmaine.org) or contact: Laura Marron Gulf of Maine Council Program Coordinator c/o NH Dept. of Environmental Services 6 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 Phone: (603) 225-5544 Fax: (603) 225-5582 Email: [email protected] OR Patricia Hinch Policy Analyst NS Department of Environment & Labour 5151 Terminal Road PO Box 697 Halifax, NS B3J 2T8 Phone: (902) 424-6345 Fax: (902) 424-0575 Email: [email protected] CITATION Hinch, P.R., S. Bryon, K. Hughes, and P.G. Wells (Editors). 2002. Sewage Management in the Gulf of Maine: Workshop Proceedings. Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment, www.gulfofmaine.org iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................vi INTRODUCTION...........................................................................1 -

Freshwater Mussels of Nova Scotia

NOVA SCOTIA MUSEUM Tur. F.o\Mli.Y of PKOVI.N C lAI~ MuSf::UMS CURATORIAL REPORT NUMBER 98 Freshwater Mussels of Nova Scotia By Derek 5. Dav is .. .. .... : ... .. Tourism, Culture and Heritage r r r Curatorial Report 98 r Freshwater Mussels of Nova Scotia r By: r Derek S. Davis r r r r r r r r r r Nova Scotia Museum Nova Scotia Department of Tourism, Culture and Heritage r Halifax Nova Scotia r April 2007 r l, I ,1 Curatorial Reports The Curatorial Reports of the Nova Scotia Museum make technical l information on museum collections, programs, procedures and research , accessible to interested readers. l This report contains the preliminary results of an on-going research program of the Museum. It may be cited in publications, but its manuscript status should be clearly noted. l. l l ,l J l l l Citation: Davis, D.S. 2007. Freshwater Mussels ofNova Scotia. l Curatorial Report Number 98, Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax: 76 p. l Cover illustration: Melissa Townsend , Other illustrations: Derek S. Davis i l l r r r Executive Summary r Archival institutions such as Museums of Natural History are repositories for important records of elements of natural history landscapes over a geographic range and over time. r The Mollusca collection of the Nova Scotia Museum is one example of where early (19th century) provincial collections have been documented and supplemented by further work over the following 143 years. Contemporary field investigations by the Nova Scotia r Museum and agencies such as the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources have allowed for a systematic documentation of the distribution of a selected group, the r freshwater mussels, in large portions of the province. -

Map (2 of 4) of Natural Resources, Graphic and Mapping Services, 2007

DESIGNATED SNOW VEHICLE AND CONNECTING SANS TRAILS Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources 65°0' 64°0' 63°0' 46°0' Tidnish Hd 46°0' Lorneville Tidnish 366 Amherst Shore r e iv R Beecham Coldspring Hd k h c s i i Settlement n w d s ia i n t T u o r c Chapman B S a Settlement Northport w v e o N N N O R T H U M B E R West Linden L A N Linden D 6 Upper S T Amherst Shinimicas Heather Beach Lower R A Gulf Shore I T Head Bridge Gulf Shore r ve he R i nc Pugwash Pla La East Harbour Fort Amherst Port Howe Pugwash Fox Harbour Lawrence Truemanville Warren Oak Lake West Fox Harbour Island sin Ba Killarney Pugwash p d i North n Hastings l l rla i e h b Amherst Wallace PICTOU ISLAND P m u r C e v i Wallace Harbour Rossendale R South Amet Sound Brookdale Malagash Pugwash Wallace Bay Wallace r Point Cape John Minudie Mansfield River ive North Shore Megs Cove Riverview wash R East Point Mount ug Pugwash Amherst P Wallace Blue Sea 104 Pleasant 301 Junction Point 204 Corner Tatamogouche Bay Seafoam C Melville A 321 Wallace Ridge South R West Little River Litttl To n e y R i v e r I B Mill Salem e R Malagash O Nappan Fenwick Leicester ive Shore CARIBOU ISLAND U Creek r Kolbec Middleboro C Conns Mills 6 Caribou Gull Point H Barronsfield Lower Richmond To n e y A 368 Barrachois River N Maccan Mills Munroes N E Harbour L Islands 6 Sand Point Marshville River Hedgeville Waterside ur Bayhead Brule arbo Boss Chignecto r Wallace John r ou H ive 307 ive arib r ck R u R C Point Lower ive la Oxford West Grant Hodson ribo R B r Ca Caribou Lower Cove ks Hansford e River Hebert Maccan r Victoria v Fo Hansford i West Poplar Lake e R French Welsford 2 ttl Streets Ridge 242 Li e Ta t a m a go u ch e River Bigney Hill c a l Logans Point l Lower Wentworth Denmark Sundridge M Birchwood R a Little Forks i Central Bay Tatamagouche v a W Mountain c W e Strathcona 204 a r Caribou View c Oxford Mahoneys a Glenville u Road J o Meadowville n Corner . -

Research Material for a Parrsborough Shore Historical Society Project

Geology and Land Grants The major geological formations along the Road to Cumberland may have influenced a wide range of human activities, including the way in which the early settlers worked and traveled in that region. These formations were both beneficial and a source of problems. They enabled the settlers who lived along the Road to work at agriculture and lumbering and settlers living in the coastal area were involved in fishing, shipbuilding, and seafaring as well as farming and lumbering. The problems were seasonal flooding of the fertile low lands along the road and erosion at certain coastal regions such as the site of the Ottawa House. The influence that landscape formations have on human activities is a broad subject and will only be briefly mentioned. The influence of geological formations on the placement of land grants will be emphasized. When the governor of Nova Scotia and his council granted land in a particular region of the province they issued a “warrant to survey” to the provincial Surveyor General. The Surveyor General, or one of the deputies, was then responsible for deciding the specific location and boundaries of the grant or grants to be issued when the survey work was completed. On the Road to Cumberland the governor issued grants over a period of time but only a few grants were issued along the northern portion of the road. These tended to be very large lots of land granted to prominent individuals. Examples include the 8000 acres at Minudie granted to J.F.W. DesBarres in 1765 and 20000 acres on the River Hebert given to Michael Francklin(Crown Land Information Management Centre,1765) in 1765. -

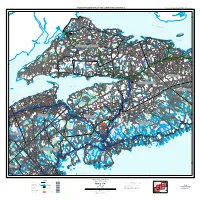

Sackville Rivers Floodplain Study: Phase I Final Report

Sackville Rivers Floodplain Study: Phase I Final Report Halifax Regional Municipality 45 Akerley Boulevard Dartmouth Nova Scotia B3B 1J7 11102282 | Report No 4 | October 30 2015 October 30, 2015 Reference No. 11102282-4 Mr. Cameron Deacoff Halifax Regional Municipality PO Box 1749 Halifax, NS B3J 3A5 Dear Mr. Deacoff: Re: Sackville Rivers Floodplain Study: Phase I Final Report GHD is pleased to provide the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM) with the attached Final Report for the Sackville Rivers Floodplain Study: Phase I. This report presents the final results for this study, including: flood and sea level frequency analyses, joint flood and sea level probability analysis, hydraulic modelling, topo-bathymetric survey data collection, and analysis of flooding factors. Data sources, methodology, and results are described in detail. Recommendations for the Phase II Study are also provided. All of which is respectfully submitted, GHD Yours truly, Juraj M. Cunderlik, Ph.D., P.Eng. Prof. Edward McBean, Ph.D., P.Eng. Project Manager QA/QC Reviewer Allyson Bingeman, Ph.D., P.Eng. Andrew Betts, M.A.Sc., P.Eng. Statistical Hydrology Specialist Hydraulic Modelling Specialist JC/jp/3 Encl. GHD Limited 45 Akerley Boulevard Dartmouth Nova Scotia B3B 1J7 Canada T 902 468 1248 F 902 468 2207 W www.ghd.com Executive Summary The lower reaches of the Sackville River have been the site of several instances of flooding over the last decade, which has been a significant issue for the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM). A Hydrotechnical Study of the Sackville River was performed in 1981, and a Hydrotechnical Study of the Little Sackville River delineated the floodplain in 1987. -

Phase 1 - Bay of Fundy, Nova Scotia Including the Fundy Tidal Energy Demonstration Project Site Mi’Kmaq Ecological Knowledge Study

Phase 1 - Bay of Fundy, Nova Scotia including the Fundy Tidal Energy Demonstration Project Site Mi’kmaq Ecological Knowledge Study Membertou Geomatics Consultants August, 2009 M.E.K.S. Project Team Jason Googoo, Project Manager Rosalie Francis, Project Advisor Dave Moore, Author and Research Craig Hodder, Author and GIS Technician Andrea Moore, Research and Database Assistant Katy McEwan, MEKS Interviewer Mary Ellen Googoo, MEKS Interviewer Lawrence Wells Sr., MEKS traditionalist Prepared by: Reviewed by: ___________________ ____________________ Dave Moore, Author Jason Googoo, Manager i Executive Summary This Mi’kmaq Ecological Knowledge Study, also commonly referred to as MEKS or a TEKS, was developed by Membertou Geomatics Consultants for the Nova Scotia Department of Energy and Minas Basin Pulp and Power Co Ltd on behalf of the Fundy Ocean Research Centre for Energy (FORCE). In January 2008, the Province of Nova Scotia announced that Minas Basin Pulp and Power Co Ltd. had been awarded the opportunity to construct a tidal energy testing and research facility in the Minas Basin, known as the Fundy Tidal Energy Demonstration Facility. This Facility will be managed by a non-profit corporation called FORCE. The objectives of this study are twofold; - to undertake a broad MEKS study for the Bay of Fundy Phase I Area as it may relate to future renewable energy projects i.e. wind, tidal and wave, specifically in Phase 1 area of the Bay of Fundy ( as identified in MGC Proposal - Minas Channel and Minas Basin), and - to undertake a more focused MEKS review specific to the Fundy Tidal Energy Demonstration Project area which would consider the land and water area potentially affected by the project, identify what is the Mi’kmaq traditional use activity that has or is currently taking place within the Project Site and Study Area and what Mi’kmaq ecological knowledge presently exists in regards to the Project Site and Study Area.