University of London Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DR SIM ZI LIN Psychologist & Autism Therapist

DR SIM ZI LIN Psychologist & Autism Therapist DR SIM ZI LIN is a Psychologist and Autism Therapist at Autism Resource Centre (Singapore), or ARC. She graduated summa cum laude from the University of California (UC), Berkeley with a BA in Psychology (Highest Honors), and was awarded a Berkeley Graduate Fellowship to further pursue a PhD in Psychology. During her graduate program, Dr. Sim researched self-directed learning in typical and atypical development, and has published and presented her work in numerous academic outlets. Her work has been featured in the Wall Street Journal as well. She received training in the neuropsychological and educational assessment for children and adolescents during her time at UC Berkeley. Passionate about serving the autism community in Singapore, Dr. Sim returned to work at Pathlight School and ARC(S) after graduating with her PhD. She is currently responsible for training and coaching new and existing staff in designing autism-friendly learning environments, incorporating students’ learning profile into one’s pedagogy, etc. She also writes and conducts therapy programmes for individuals with autism in areas including self-regulation, assertiveness and self-advocacy. She is also involved in conducting cognitive, academic, and mental capacity assessments for students with autism to support Access Arrangements and Deputyship applications. Holding the quote “If a child can't learn the way we teach, maybe we should teach the way they learn” (Ignacio Estrada) close to her heart, Dr. Sim continues to pursue her research interests in examining learning mechanisms in children with ASD. Autism Resource Centre (S) Autism Intervention, Training & Consultancy GST no. -

WHICH SCHOOL for MY CHILD? a Parent’S Guide for Children with Special Educational Needs © Nov 2018 Ministry of Education, Republic of Singapore

WHICH SCHOOL FOR MY CHILD? A Parent’s Guide For Children with Special Educational Needs © Nov 2018 Ministry of Education, Republic of Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the copyright owners. All contents in this book have been reproduced with the knowledge and prior consent of the talents concerned, and no responsibility is accepted by author, publisher, creative agency, or printer for any infringement of copyright or otherwise, arising from the contents of this publication. Every effort has been made to ensure that credits accurately comply with information supplied. We apologise for any inaccuracies that may have occurred and will resolve inaccurate information or omissions in a subsequent reprinting of the publication. Published by Ministry of Education 51 Grange Road Singapore 249564 www.moe.gov.sg Printed in Singapore Available online at MOE’s website at WHICH https://www.moe.gov.sg/education/special-education SCHOOL FOR MY CHILD? A Parent’s Guide For Children with Special Educational Needs A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE This guide is written to help parents understand how to identify a school that best supports their children with special educational needs (SEN). Some children with SEN need extra help with their education. For some, the extra help can be provided within a UNDERSTANDING YOUR CHILD’S mainstream school. Other children may need more intensive NEEDS AND GETTING SUPPORT and customised support that can only be offered by Special Understand Special Educational 5 Education (SPED) schools. Children with SEN can realise Needs (SEN) their full potential and lead meaningful and purposeful lives Find a Qualified Professional 6 if they are given educational support that is well-matched Get Your Child Assessed 7 to their needs. -

Prevalence, Diagnosis, Treatment and Research on Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asd) in Singapore and Malaysia

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SPECIAL EDUCATION Vol 29, No: 3, 2014 PREVALENCE, DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT AND RESEARCH ON AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS (ASD) IN SINGAPORE AND MALAYSIA Tina Ting Xiang Neik SEGi University Lay Wah Lee Hui Min Low Universiti Sains Malaysia Noel Kok Hwee Chia Arnold Chee Keong Chua Nanyang Technological University The prevalence of autism is increasing globally. While most of the published works are done in the Western and European countries, the trend in autism research is shifting towards the Asian continent recently. In this review, we aimed to highlight the current prevalence, diagnosis, treatment and research on Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Singapore and Malaysia. Based on database searches, we found that the awareness about autism among lay and professional public is higher in Singapore compared to Malaysia. The special education system and approach towards autism treatment is also different between both societies although the culture is similar and the geographic location is close. Main findings and implications were discussed in this review. The lack of study on autism prevalence in this part of the world commands a critical need for further research. Perhaps more collaborative work between both countries could be done to expand the knowledge in autism. Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a type of neurodevelopmental disorder affecting the mental, emotion, learning and memory of a person (McCary et al., 2012). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), ASD is characterized by three features. Firstly, impairment of social interaction, which includes but not limited to impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviours such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures and gestures to regular social interaction. -

Redesigning Pedagogy

Home NIE Follow Us: Home Current Issue Previous Issues Browse Topics Resources Contributions About Contact Home › Previous Issues › issue 56 mar 2016 Most Read Articles issue 56 mar 2016 6,975 views The Importance of Equity in Singapore Education Effective Communication issue 56 mar 2016 Singapore is known for providing highquality education but how is it doing in terms of … 4,409 views Continue reading → From the Field to the Geography Classroom Inclusive Education for All Students 2,952 views issue 56 mar 2016 Educational equity comprises many different aspects, The Big Picture in Social including appropriate access to education and inclusion. It Studies can … Continue reading → Subscribe Email Address Confident Teachers Make for Confident Learners issue 56 mar 2016 A confident teacher would have a positive impact on his or First Name her students’ achievement, attitude, … Continue reading → Subscribe Working with Parents to Support Students Tags issue 56 mar 2016 It takes a village to raise a child. Schools today are Alternative assessment Assessment recognizing the importance of … feedback Assistive technology Character Continue reading → building Character education Classroom engagement Classroom relationship Cognitive diagnostic assessments Disciplinary literacy Field trip Fieldwork Formative A Culture of Care assessment History Holistic issue 56 mar 2016 education Humanities In mainstream schools, there are some students with special Imagination Inclusive education needs who might need a little … Learning Learning environment -

ACHIEVING INCLUSION in EDUCATION Understanding the Needs Oƒ Students with Disabiiities

ACHIEVING INCLUSION IN EDUCATION Understanding the needs oƒ students with disabiIities Produced by: Sponsored by: Copyright © 2016 by Disabled People’s Association, Singapore All rights reserved. No part nor entirety of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of DPA. 2 Contents List of Abbreviations 4 Introduction 6 Structure 7 Methodology 7 Part I: Educational Situation 9 Background 9 Initiatives for pre-school children 10 Initiatives for students in mainstream schools 11 Initiatives for students in special education schools 14 Government subsidies and funds 16 Part II: Barriers to Education 19 Attitudinal barriers 19 Physical barriers 21 Information barriers 21 Systemic barriers 22 Transportation barriers 26 Part III: Recommendations 27 Attitudinal change 27 Information 28 Physical accessibility 29 Systemic solutions 30 Transportation solutions 34 Part IV: Inclusive Education 35 What is inclusive education? 35 Five myths about inclusive education 37 Conclusion 39 Glossary 40 References 44 4 List of Abbreviations AED(LBS) Allied Educator (Learning and Behavioural Support) ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder ATF Assistive Technology Fund BCA Building and Construction Authority CRC Convention on the Rights of Children CRPD Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities DPA Disabled People’s Association IHL Institute of Higher Learning ITE Institute of Technical Education MOE Ministry of Education MSF Ministry of Social and Family Development NCSS National Council of Social Service NIE National Institute of Education SDR School-based Dyslexia Remediation SEN Special Education Needs SPED (School) Special Education School SSI Social Service Institute TSN Teachers trained in Special Needs UN United Nations VWO Voluntary Welfare Organisation 5 “EVERY CHILD HAS A DIFFERENT LEARNING STYLE AND PACE. -

WEB Full Programme 20Jun.Xlsx

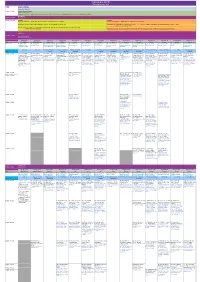

CONFERENCE DAY 01 Thursday 20 June 2019 8:00am Start of Registration 9:00am Conference Opening Venue: West Ballroom 9:30am - 10:30am Opening Keynote Address Venue: West Ballroom Presenter: Prof. Patricia Howlin, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK - Predictive Factors for Improving the Lifetime Outcomes of Individuals with Autism Morning Tea 10:30am - 11:00am Venue: Foyer 11:00am - 12:30pm Plenary 1 Plenary 2 Venue: West Ballroom Chairperson: Ms. Loh Wai Mooi, Autism Resource Centre (Singapore) Venue: Central Ballroom Chairperson: Mr. Adrian Ford, Aspect Australia Presenter 1: Dr. Damian Milton, National Autistic Society, UK - Becoming Autistic: A Father’s Story Presenter 1: Dr. William Mandy, University College London - The Hidden Face of Autism: Understanding the Characteristics and Needs of Girls and Women on the Autism Spectrum Presenter 2: Dr. Tom Tutton, Autism Spectrum Australia (Aspect) - Inclusion: An Autism Specific Organisation Working Towards “Nothing About Us – Without Us” Presenter 2: Dr. Dawn-Joy Leong, Independent Researcher & Multi-Artist, Singapore - Autistic Thriving - Not Despite But Because of Autism Lunch Venue: Foyer 12:30pm - 2:00pm Posters Presentation Venue: Central Inner Foyer Concurrent 1 Concurrent 2 Concurrent 3 Concurrent 4 Concurrent 5 Concurrent 6 Concurrent 7 Concurrent 8 Concurrent 9 Concurrent 10 Concurrent 11 Concurrent 12 Concurrent 13 Concurrent 14 Room West Ballroom Central Ballroom Gemini 1-2 Aquarius 4 Leo 1 Leo 2 Leo 3 Leo 4 Pisces 1 Pisces 2 Pisces 3 Pisces 4 Virgo 1 Virgo 2 Chairperson Dr. Sylvia Choo, Ms. Alina Chua, Ms. Salwanizah Mohd Ms. Wong Kah Lai, Ms. Tan Sze Wee, Mr. Liak Teng Lit, Ms. -

The Journal of Reading and Literacy Vol.4 (2012)

1 Journal of Reading and Literacy Volume 4, 2012 2 The Journal of READING FOR AN READING INCLUSIVE SOCIETY & LITERACY An e-publication of the Society for Reading and Literacy The JRL Editorial Board Adviser: Ms Serene Wee, President of the Society for Reading and Literacy. Coordinating Editors: Asst/P Noel Kok Hwee Chia, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University Mr Norman Kiak Nam Kee, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University SRL Representative Editor: Dr Ng Chiew Hong, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University Review Editors: Ast/P Meng Ee Wong, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University Dr Benny Lee, Singapore Institute of Management University Dr Winston P.N. Lee, National University of Singapore Mr Mohd Shaifudin Bin Md Yusof, School of Humanities, Ngee Ann Polytechnic Mr Bob T.M. Tan, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia Dr Li Jenyi, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University Asst/P Ludwig Tan, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University Dr Gilbert Yeoh, National University of Singapore Aims and Scope The Journal of Reading and Literacy (JRL) is the official journal of the Society for Reading and Literacy, Singapore. This is a refereed journal with interests in reading and literacy issues in both mainstream (including adult education) and special education settings. The journal welcomes manuscripts of diverse and interdisciplinary themes in the aim of improving reading and literacy. Literacy is contextualized within a broad interpretation including traditional literacy, literacy standards, early and/or emergent literacy, comprehensive literacy, content area literacy, adolescent literacy, functional literacy, adult literacy, multimedia literacy, multicultural literacy, literacy and technology as well as any other interpretation that is of interest to the readers and the Editorial Board. -

UOB Donates 1000 Care Packs to Help Disadvantaged Families to Fend Off

UOB donates 1,000 care packs to help disadvantaged families to fend off COVID-19 20 student volunteers from Pathlight School lending a helping hand to prepare UOB Heartbeat care packs. These care packs will be distributed to disavantaged families to help them fend off COVID-19. Singapore, 20 February 2020 – United Overseas Bank (UOB) has teamed up with Central Singapore Community Development Council (CDC) and Pathlight School to provide UOB Heartbeat care packs to needy residents to help them protect against COVID-19. Ms Lilian Chong, Executive Director, Group Strategic Communications and Brand, UOB, said, “Families in Singapore are doing their best to protect and to care for their loved ones during this protracted period of uncertainty. Knowing this, we wanted to help those who might not have the resources that others do to procure essentials such as surgical face masks and anti-bacterial gels which are in high demand. Working together with our partners and volunteers, we are giving care packs which include these products to support the members of our community and to keep the good going.” 1 UOB employee volunteers sourced for and acquired 1,000 sets of essential items for the residents. Each UOB Heartbeat care pack comprises five surgical face masks, a bottle each of anti-bacterial handwash and hand sanitiser, and two bottles of Vitamin C pastilles. The care packs were put together by student volunteers from Pathlight School and will be distributed to needy residents in the Central Singapore District from 22 February. Ms Denise Phua, Mayor of Central Singapore, said, “Singapore can only be stronger when we continue to look out for one another and not hesitate to take practical steps to support the more vulnerable amongst us. -

Professional Practice Guidelines

1 Published by Ministry of Education, Singapore Special Educational Needs Division 51 Grange Road Singapore 249564 Copyright © 2018 by Ministry of Education, Singapore ISBN 978-981-11-9273-9 2 CONTENTS Foreword Introduction 6 Chapter 1: Definitions 1.1 Psycho-educational Assessment 8 1.2 Special Educational Needs (SEN) 8 1.3 Educational Placement 9 1.4 Compulsory Education 9 Chapter 2: Psycho-educational Assessment Data 2.1 Sources of Assessment Data 14 2.2 Areas of Assessment 14 2.3 User of Psycho-educational Assessment Tools and Data 15 2.4 Factors to Consider in Selecting and Using Different Psycho-educational Assessment Measures 16 2.4.1 Norm-referenced/Standardised Tests 16 2.4.2 School-based Tests 17 2.4.3 Direct Observations 17 2.4.4 Reports by Caregivers and Teachers 18 2.4.5 Self-Reports 18 Chapter 3: Assessment for Specific Purposes 3.1 Assessment to Ascertain Appropriate Special Educational Placement 21 3.2 Ascertaining Student’s Suitability for Placement into a Mainstream School 22 3.3 Ascertaining Student’s Suitability for Placement into an Appropriate Special Education (SPED) School 22 3.4 Assessment for Access Arrangements and Curricular Exemption 23 3 Chapter 4: Assessment Considerations for Specific Populations 4.1 Visual Impairment 28 4.2 Hearing Loss 30 4.3 Central Auditory Processing Disorder 31 4.4 Cerebral Palsy and Other Significant Motor Impairments 32 4.5 Developmental Coordination Disorder 34 4.6 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder 35 4.7 Dyslexia 37 4.8 Language Disorder 38 4.9 Speech Sound Disorder 40 -

Special Needs Schools Sprouting up They Cater for Expats, As Well As Singaporeans Put Off by Long Wait at Govt-Funded Schools

Printed from straitstimes.com 7/11/11 6:28 PM « Return to article Print this The Straits Times www.straitstimes.com Published on Nov 7, 2011 Privately run special needs schools sprouting up They cater for expats, as well as Singaporeans put off by long wait at govt-funded schools By Theresa Tan WHEN Mr Rob Steeman, 48, was offered a high-flying job in Singapore two years ago, he and his wife agreed that their decision to move would hinge on one factor: Can they find a good school for their three disabled children? The Dutch couple - who lived in the United States and Norway before coming to the Republic - know only too well the difference a good school can have on their children's well-being. Mrs Fedra Steeman, a 44-year-old housewife, said their eldest daughter, Solveig, 14, was unhappy at her previous school in Norway. The girl, who suffers from cerebral palsy, was getting little help from her teachers and could not read even though she has a 'normal intelligence'. Also temperamental was their second son, Kjell, 11, who suffers from autism and bipolar disorder. Meanwhile, their youngest daughter, Pippi, eight, who is also autistic, was not talking. The couple have two other children, Ingmar, 17, and Liv, 10. When the Steemans found the Genesis School for Special Education here, they packed their bags and came. Mrs Steeman, whose husband is a vice-president in a firm that produces solar panels, said: 'Genesis School is absolutely fabulous. Our children made such incredible progress there.' At Genesis, Solveig learnt how to read and is much happier. -

Singapore Airlines Showcases Artists with Special Needs

Singapore Airlines showcases artists with special needs By Rachel Debling on June, 1 2018 | Airline & Terminal News Singapore Airlines (SIA), SG Enable and the Autism Resource Centre (ARC) have formed a partnership that will have the works of artists with special needs displayed on SIA’s inflight products, starting with snack boxes coming to the airline in June 2018. This program marks the first initiative of SG Enable’s “i’mable” campaign, a marketplace for goods and products created by persons with disabilities. The work of artists with special needs will be displayed on SIA's network to help promote the inclusion of persons with disabilities globally. The first products being introduced as part of this campaign are Economy Class snack boxes featuring artwork by artists with autism from the Artist Development Programme (ADP) which is an initiative under Pathlight School, a program under ARC. More inflight products with such artwork will be released as the program continues. Aaron Yap will be the first ADP artist to have work featured on the snack boxes – a design called "Local Food" that features local cuisine such as satay, claypot rice and kueh lapis. Customers can learn how to play a part in promoting inclusiveness with information and suggestions on each box, such as visiting the Enabling Village, an inclusive community space in Singapore. Ms Ku Geok Boon, Chief Executive Office of SG Enable, commented: “This ground-up collaboration with SIA and ARC shows how corporates can work with the disability sector to achieve greater social impact.” “Singapore Airlines recognizes the importance of giving back to the communities that we serve," Mr Yeoh Phee Teik, Acting Senior Vice President, Customer Experience at Singapore Airlines, said in a statement. -

Special Education (Sped) Schools Run by Voluntary Welfare Organisations for Children with Special Needs in Singapore

International Journal for Studies on Children, Women, Elderly And Disabled, Vol. 3, (January) ISSN 0128-309X 2018 SPECIAL EDUCATION (SPED) SCHOOLS RUN BY VOLUNTARY WELFARE ORGANISATIONS FOR CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS IN SINGAPORE Hajar Bt Mohd Salleh Sahimi ABSTRACT About 1 in 150 children in Singapore was diagnosed with developmental issues. This is higher than World Health Organisation (WHO) data, which is 1 in 160. The Singapore Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) decided to set up a steering committee to develop the 3rd Enabling Masterplan. The aim for this 5-year national plan is to empower and enable people with disabilities. There are many services developed in order to support these children from infant to school going age. As of 2010, there are 20 special education schools run by 13 different Voluntary Welfare Organisations (VWO). They run different programs catering different level of disabilities. This article is to discuss about the special education schools that are run by VWOs in Singapore, the comparison with mainstream schools, and also about inclusive education. The goal is to understand how different forms of education is affecting children with special needs in order to ultimately help placing these children in the appropriate school. Keyword: Special education school, Singapore schools, Voluntary Welfare Organisation. 1. INTRODUCTION About 1 in 150 children in Singapore was diagnosed with developmental issues. The number of children diagnosed with developmental issues increased 76% from 2500 people in 2010 to 4400 people in 2014. (MSF 2016) This increase in number of children diagnosed might be due to early detection and early diagnosis by a trained professional.