33-4 Fullfile Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God Games’, with the Player Supposedly Given Omnipotent Control Over the Game Environment, Revealing the Enduring Presence of the Second-Creation Narrative

Smith, B. T. L. (2017). Resources, Scenarios, Agency: Environmental Computer Games. Ecozon@, 8(2), 103-120. http://ecozona.eu/article/view/1365 Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Universidad de Alcale at http://ecozona.eu/article/view/1365 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Resources, scenarios, agency: environmental computer games Abstract In this paper I argue that computer games have the potential to offer spaces for ecological reflection, critique, and engagement. However, in many computer games, elements of the games’ procedural rhetoric limit this potential. In his account of American foundation narratives, environmental historian David Nye notes that the ‘second-creation’ narratives that he identifies “retain widespread attention [...] children play computer games such as Sim City, which invite them to create new communities from scratch in an empty virtual landscape…a malleable, empty space implicitly organized by a grid” (Nye, 2003). I begin by showing how grid-based resource management games encode a set of narratives in which nature is the location of resources to be extracted and used. I then examine the climate change game Fate of the World (2011), drawing it into comparison with game-like online policy tools such as the UK Department for Energy and Climate Change’s 2050 Calculator, and models such as the environmental scenario generation tool Foreseer. -

7:30 A.M. – AUDIT CONFERENCE PARK COMMISSIONERS and PARK DISTRICT AUDIT COMMITTEE (Pursuant to Section 121.22 (D) (2) of the Ohio Revised Code)

BOARD OF PARK COMMISSIONERS OF THE CLEVELAND METROPOLITAN PARK DISTRICT THURSDAY, MARCH 14, 2019 Cleveland Metroparks Administrative Offices Rzepka Board Room 4101 Fulton Parkway Cleveland, Ohio 44144 7:30 A.M. – AUDIT CONFERENCE PARK COMMISSIONERS AND PARK DISTRICT AUDIT COMMITTEE (Pursuant to Section 121.22 (D) (2) of the Ohio Revised Code) 8:00 A.M. – REGULAR MEETING AGENDA 1. ROLL CALL 2. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 3. MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING FOR APPROVAL OR AMENDMENT • Regular Meeting of February 14, 2019 Page 88339 4. FINANCIAL REPORT Page 01 5. NEW BUSINESS/CEO’S REPORT a. APPROVAL OF ACTION ITEMS i) General Action Items (a) Chief Executive Officer’s Retiring Guest(s): • Terry L. Robison, Director of Natural Resources Page 07 • Stephen J. Schulz, Education Specialist Page 08 • Virginia G. Viscomi, Service Maintenance II Page 08 (b) 2019 Budget Adjustment No. 2 Page 09 (c) Revision of Rates and User Fees Page 10 (d) Club Metro 2019 Financial Request Page 10 (e) RFP #6149: Golf Cars Page 11 (f) Edgewater Marina Operations – Lease Agreement Page 12 (g) Whiskey Island Marina Operations – Management Services Agreement Page 14 (h) Branded Product Sponsor and Suppler of Beverages Agreement – Page 15 Amendment No. 2 (i) Contract Amendment – RFP #6344-B: Bonnie Park Ecological Restoration Page 16 and Site Improvement Project – Mill Stream Run Reservation -GMP 1 (j) Professional Services Agreement – RFQu #6402: Bridge Inspection and Page 18 Engineering Support Program 2019-2014; and 2020 Bridge Inspections and Summary Reports Proposal (k) Authorization of Funds – Whiskey Island Marina Emergency Repair – Page 21 Wind Damage (l) Nomination of Joseph V. -

DEMO Magazine

ISSUE 18 SPRING/SUMMER 2013 DEMOThe Alumni Magazine of Columbia College Chicago The avant-garde fashion designs of AGNES HAMERLIK Revitalizing Detroit with PHILLIP COOLEY Lessons learned on KICKSTARTER May 17, 2013 ALUMNI AT Want to perform? Volunteer? Or just come out and be a part of the awesome Manifest audience? If you are an alumnus and would like an application to perform on the Alumni Stage, contact Cyn Vargas at [email protected]. Stop by, sit back, and ALUMNI LOUNGE relax in our alumni ALUMNI & lounge! You'll enjoy your Noon – 7PM fellow alumni performers GRADUATION PARTY singing, reciting, dancing, 623 South Wabash and other cool stuff. 8PM – 11PM Quincy Wong Center Hilton Chicago for Artistic Expression 720 S. Michigan Ave. Grand Ballroom colum.edu/alumnimanifest Art: Thumy Phan, Manifest Creative Director Creative Phan, Manifest Art: Thumy ’12) Jacob Boll (BA Photos: CONTENTS DEMO ISSUE 18 SPRING/SUMMER 2013 18 11 FEATURES PORTFOLIO SPOT ON DEpaRTMENTS 8 22 30 Justin “Nordic Thunder” 03 Vision A question for Howard (BA ’07) reigns as President Carter KICKSTART MY ART LIFE DURING king in the competitive world Columbia alumni, students, WARTIME of air guitar. 04 Wire News from the and faculty share lessons Photographer Andrew Nelles Columbia community learned on their way to crowd- (BA ’08) recounts his days 32 Karine Saporta (BA ’72), funding success. covering American troops in knighted in France, 38 Alumni News & Notes By Stephanie Ewing (MA ’12) Afghanistan. As told to Andrew stays in demand as a Featuring class news, notes, Greiner (BA ’05) dancer, choreographer, and networking 14 and photographer. -

Vlaams Audiovisueel Fonds

VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS . jaarverslag 2018 VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS . jaarverslag 2018 uitgegeven door het .VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS vzw huis van de vlaamse film bischoffsheimlaan 38 - 1000 brussel [email protected] vaf.be Met de steun van de Vlaamse minister van Cultuur, Media, Jeugd en Brussel en de Vlaamse minister van Onderwijs INHOUD . jaarverslag 2018 VOORWOORDEN FINANCIEEL CREATIE TALENT- ONTWIKKELING •4 •7 •15 •26 COMMUNICATIE & PUBLIEKSWERKING GAMEFONDS SCREEN PROMOTIE FLANDERS •39 •47 •53 •67 DUURZAAM KENNISOPBOUW WERKING VLAAMSE FILM FILMEN IN CIJFERS •73 •77 •81 •89 Toen ik in mei vorig jaar op het Festival Deze maatregelen zullen ongetwijfeld om op dit vlak lessen te trekken. van Cannes de film Girl te zien kreeg, hun vruchten afwerpen. Toch wil ik een Het is duidelijk dat we erin geslaagd zijn voelde ik aan de stilte in de zaal bij warme oproep doen aan de volgende om ook dit jaar als VAF op verschillende de aftiteling welke magie er uitging Vlaamse Regering voor extra middelen vlakken toonaangevend te zijn. Hopelijk VOORWOORD van het brengen van zo’n mooi en in de nieuwe bestuursperiode. Er kunnen we in de toekomst op dit elan ontroerend verhaal. De tsunami aan werden in het verleden reeds extra doorgaan. Met het huidige team van Alles start met een prijzen die de film in ontvangst mocht middelen vrijgemaakt voor het VAF/ medewerkers heb ik er als voorzitter nemen, was ongezien. We mogen als Mediafonds en het VAF/Gamefonds die alvast het volste vertrouwen in. n goed verhaal VAF bijzonder fier zijn dat we mee aan zeker een boost gegeven hebben. -

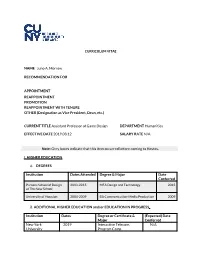

NAME Juno A. Morrow RECOMMENDATION FOR

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Juno A. Morrow RECOMMENDATION FOR APPOINTMENT REAPPOINTMENT PROMOTION REAPPOINTMENT WITH TENURE OTHER (Designation as Vice President, Dean, etc.) CURRENT TITLE Assistant Professor of Game Design DEPARTMENT Humanities EFFECTIVE DATE 2019.08.12 SALARY RATE N/A Note: Grey boxes indicate that this item occurred before coming to Hostos. I. HIGHER EDUCATION A. DEGREES Institution Dates Attended Degree & Major Date Conferred Parsons School of Design 2013-2015 MFA Design and Technology 2015 at The New School University of Houston 2004-2009 BA Communication-Media Production 2009 B. ADDITIONAL HIGHER EDUCATION and/or EDUCATION IN PROGRESS Institution Dates Degree or Certificate & (Expected) Date Major Conferred New York 2019 Interactive Telecom. N/A University Program Camp II. EXPERIENCE A. TEACHING EXPERIENCE Institution Department Rank Dates CUNY—Eugenio María de Hostos Humanities Assistant Professor 2015- Community College Present Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Technology Part-time Lecturer 2015 Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Technology Teaching Fellow 2014 Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Teaching Assistant 2014 Technology B. OTHER EXPERIENCE Institution Department Rank or title role Dates (Independent/Freelance) N/A Photographer/Designer 2009- Present Try The World N/A Front-End Web Developer 2015 Parsons School of Design gadgITERATION Graduate Research 2014-2015 Assistant Reed Elsevier Universal Access Research Coordinator 2012-2013 HASH magazine Photography Staff Photographer 2012-2013 HRP/CoxReps -

The Fuzzy Software Patent Debate Rages On

OPINION The Fuzzy Software Patent Debate Rages On By Heather J. Meeker LinuxInsider 02/23/05 5:00 AM PT Once upon a time, we intellectual property lawyers got to live peacefully in our ivory towers. Now it seems that intellectual property policy issues have become fraught with partisan rhetoric. Most open-source promoters are against software patents. Most corporate spokesmen side with patents, period, whether they cover software or not. But it is worth looking beyond the rhetoric. The European Commission recently tolled the death knell for the EU Software Patent Directive, or more precisely, the "Directive on the Patentability of Computer- Implemented Inventions." Like most Americans, I am fairly clueless about the EU political process, and I wouldn't presume to write about exactly how it was killed. But the decision may have been swayed by an eleventh-hour public relations pitch against the directive by open-source spokesmen from the United States. On that aspect, I will add my two cents. A delegation of open-source leaders, led by Linus Torvalds, published an "Appeal" at softwarepatents.com, calling software patents "dangerous to the economy at large, and particularly to the European economy." Look Beyond the Rhetoric Leaders of the open-source software movement have long been harsh critics of software patents. The GPL [license] itself says, "any free program is threatened constantly by software patents." The appeal contends that copyright provides adequate protection for the creations of software authors. The Appeal advocated reliance on copyright law, rather than patent law, for the protection of software. Not long afterward, in late January, the European Parliament's Legal Affairs Committee recommended scrapping the pending directive, extending the debate until at least the end From www.linuxinsider.com/story/40676.html 1 April 2011 of the year. -

Biden Calls for New Gun Laws As Shootings Rekindle Debate

P2JW083000-6-A00100-17FFFF5178F ****** WEDNESDAY,MARCH 24, 2021 ~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.68 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 32423.15 g 308.05 0.9% NASDAQ 13227.70 g 1.1% STOXX 600 423.31 g 0.2% 10-YR. TREAS. À 13/32 , yield 1.637% OIL $57.76 g $3.80 GOLD $1,724.70 g $13.10 EURO $1.1851 YEN 108.58 Boulder Mourns Victims as Suspect Is ChargedWith Murder Intel Sets What’s News Strategy To Speed Business&Finance Its Chip ntel’snew CEO is fast Itracking effortstorevive the semiconductor giant Revival with abroad plan that mixes increased outsourcing with acommitment to spend $20 Semiconductor maker billion on newfactories. A1 earmarks $20 billion Powell, in a joint appear- ancewith Yellen on Capitol GES to expand U.S. plants, Hill, said he doesn’t expect IMA will boost outsourcing the $1.9trillion stimulus package will lead to an unwel- GETTY SE/ BY AARON TILLEY come increase in inflation. A2 U.S. stocks ended lower Intel Corp.’snew chief exec- afterthe testimonybyPowell ANCE-PRES utiveisfast tracking effortsto FR and Yellen, with the S&P 500, revivethe semiconductor gi- Dowand Nasdaq losing 0.8%, ENCE ant with abroad plan that AG 0.9% and 1.1%, respectively. B11 Y/ mixes increased outsourcing with acommitment to spend Robinhood Marketsfiled NNOLL $20 billion on newfactories paperworkwith the SEC for CO that could help addressa what is suretobeone of the ON global chip shortage. year’s most eagerly awaited JAS IN MEMORY: People gather foracandlelight vigil Tuesdaynight to honor the 10 victims killedMondaybyagunman at a Pat Gelsinger said Tuesday initial public offerings. -

Bowl Round 8

USABB National Bowl 2016-2017 Round 8 Round 8 First Half (Tossup 1) This leader's eunuch Zhao Gao managed to alter the line of succession by convincing this leader's son Fusu to commit suicide. This man was advised by Li Si, who inspired him to target the Hundred Schools of Thought, bury (*) Confucian scholars alive, and burn their teachings. This man defeated the state of Zhao to end the Warring States period in 221 BC. A large terracotta army was designed for the burial tomb of, for ten points, what first emperor of China and founder of the Qin [chin] dynasty? ANSWER: Qin Shi Huangdi (accept Ying Zheng or Zhao Zheng) (Bonus 1) This man consolidated power over Italy with his blackshirts in the March on Rome. For ten points each, [Part A] Name this leader of Italy before and during World War II, nicknamed \Il Duce." ANSWER: Benito Mussolini [Part B] Mussolini was a proponent of this far-right political ideology, which emphasizes the state over the individual via an authoritarian ruler. ANSWER: fascism (accept word forms) [Part C] Mussolini established Italian East Africa after his conquest of this country in 1936, which had been ruled at the time by Haile Selassie. ANSWER: Ethiopia (accept Abyssinia) (Tossup 2) A character in this story brings home an invitation to Georges Rampouneau's [rom-poo-NOH's] party, and sleeps in a side room while his wife dances until four in the morning. The central object of this story is only worth five hundred francs, but the (*) Loisels [lwah-ZELLS] nevertheless incur massive debt in order to repay Madame Forestier [foh-res-tee-AY] when that object is lost at a ball. -

Egx Rezzed the Trpg

1: An anticapitalist and 2: An inscrutably baroque 3: An autobiographical 4: A hideously early access 5: A stealth-focused Present 6: A rhythm-based 7: An “apolitical” by Grant Howitt & Nate Crowley 8: A neon-drenched 9: An impossibly long 10: A free-to-play 1: Metroidvania THE INDIE GAME YOU ARE SUPER 2: “Wholesome” EXCITED TO PLAY AT REZZED 3: Couch co-op is generated by rolling on the tables 4: Pay-to-win to the right. Each player rolls up a 5: VR YOU ARE ATTENDING REZZED, game of their own, which they’ve 6: Massively Multiplayer THE COOL AND WELL KNOWN been excited about for years: 7: Viciously difficult GAMING SHOW... 8: Bullet hell But can you make it to the You know it’s in there somewhere. 9: FMV end of the day, having played But between you and that game 10: Roguelike the one game you’re desperate you’ve salivated over for decades to play, and without bursting is the show itself: a gauntlet 1: Arena shooter in to tears from fatigue and of overenthusiastic developers, 2: Garden simulator hunger? Can you maintain the bellowing streamers, brutally 3: Metaphor for depression separation between fantasy slow refreshment vendors, and 4: Dark Souls clone and reality? cosplayers walking twelve abreast 5: Visual novel And is the monstrous through the ten miles of winding 6: Historical RTS chimera hunting you through catacombs that comprise the 7: Ambient Storytelling Experience Tobacco Dock a genuine threat, Tobacco Dock venue. And you’re 8: Factory-making game or merely your imagination? certain there’s a minotaur in there 9: Tower Defence game Let’s find out! somewhere, too. -

Patenting Software Is Wrong

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 58 Issue 2 Article 7 2007 Manuscript: You Can't Patent Software: Patenting Software is Wrong Peter D. Junger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter D. Junger, Manuscript: You Can't Patent Software: Patenting Software is Wrong, 58 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 333 (2007) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol58/iss2/7 This Tribute is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. MANUSCRIPT* YOU CAN'T PATENT SOFTWARE: PATENTING SOFTWARE IS WRONG PeterD. Jungert INTRODUCTION Until the invention of programmable' digital computers around the time of World War II, no one had imagined-and probably no one could have imagined-that methods of solving mathematical . Editor'sNote: This article is the final known manuscript of Professor PeterJunger. We present this piece to you as a tribute to Professor Junger and for your own enjoyment. This piece was not, at the time of ProfessorJunger 's passing, submitted to any Law Review or legal journal.Accordingly, Case Western Reserve University Law Review is publishing this piece as it was last edited by Professor Junger, with the following exceptions: we have formatted the document for printing, and corrected obvious typographical errors. Footnotes have been updated to the best of our ability, but without Professor Junger's input, you may find some errors. -

A Symposium for John Perry Barlow

DUKE LAW & TECHNOLOGY REVIEW Volume 18, Special Symposium Issue August 2019 Special Editor: James Boyle THE PAST AND FUTURE OF THE INTERNET: A Symposium for John Perry Barlow Duke University School of Law Duke Law and Technology Review Fall 2019–Spring 2020 Editor-in-Chief YOOJEONG JAYE HAN Managing Editor ROBERT HARTSMITH Chief Executive Editors MICHELLE JACKSON ELENA ‘ELLIE’ SCIALABBA Senior Research Editors JENNA MAZZELLA DALTON POWELL Special Projects Editor JOSEPH CAPUTO Technical Editor JEROME HUGHES Content Editors JOHN BALLETTA ROSHAN PATEL JACOB TAKA WALL ANN DU JASON WASSERMAN Staff Editors ARKADIY ‘DAVID’ ALOYTS ANDREW LINDSAY MOHAMED SATTI JONATHAN B. BASS LINDSAY MARTIN ANTHONY SEVERIN KEVIN CERGOL CHARLES MATULA LUCA TOMASI MICHAEL CHEN DANIEL MUNOZ EMILY TRIBULSKI YUNA CHOI TREVOR NICHOLS CHARLIE TRUSLOW TIM DILL ANDRES PACIUC JOHN W. TURANCHIK PERRY FELDMAN GERARDO PARRAGA MADELEINE WAMSLEY DENISE GO NEHAL PATEL SIQI WANG ZACHARY GRIFFIN MARQUIS J. PULLEN TITUS R. WILLIS CHARLES ‘CHASE’ HAMILTON ANDREA RODRIGUEZ BOUTROS ZIXUAN XIAO DAVID KIM ZAYNAB SALEM CARRIE YANG MAX KING SHAREEF M. SALFITY TOM YU SAMUEL LEWIS TIANYE ZHANG Journals Advisor Faculty Advisor Journals Coordinator JENNIFER BEHRENS JAMES BOYLE KRISTI KUMPOST TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors’ Biographies ................................................................................ i. John Perry Barlow Photograph ............................................................... vi. The Past and Future of the Internet: A Symposium for John Perry Barlow James Boyle -

As of July 23, 2018) the 100% Green Power Users List Represents the Partners That Are Using Green Power to Meet 100 Percent of Their U.S

100% Green Power Users (as of July 23, 2018) The 100% Green Power Users list represents the Partners that are using green power to meet 100 percent of their U.S. organization-wide electricity use. The combined green power use of these 996 organizations amounts to nearly 24 billion kilowatt-hours of green power annually, which is equivalent to the electricity use of nearly 2.2 million average American households each year. Partner Name Annual GP % of Organization Providers Green State Green Total Type (listed in Power Power Electricity descending Resources Usage Use* order by (kWh) kWh supplied to Partner) Microsoft Corporation 4,557,278,000 100% Technology & Sterling Planet°, Solar, Wind WA Telecom Enbridge LLC, EDF Renewable Energy, Black Hills Corp., Renewable Choice Energy°, On-site Generation Intel Corporation 4,152,034,623 100% Technology & Renewable Biomass, CA Telecom Choice Energy°, Geothermal, 3Degrees°, On- Small-hydro, site Generation, Solar, Wind PNM Google Inc. 2,409,051,735 53% Technology & MidAmerican Biogas, Small- CA Telecom Energy°, NextEra hydro, Solar, Energy Wind Resources°, Grand River Dam Authority°, Northern Wasco County PUD, Enel Green Power Partner Name Annual GP % of Organization Providers Green State Green Total Type (listed in Power Power Electricity descending Resources Usage Use* order by (kWh) kWh supplied to Partner) North America, Exelon Generation, EDF Renewable Energy, On-site Generation, Duke Energy Apple Inc. 1,650,398,166 107% Technology & On-site Biogas, CA Telecom Generation, 3 Biomass, Small-