Native Soldiers.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Fatal Casualties on D-Day

Canadian Fatal Casualties on D-Day (381 total) Data from a search of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, filtered by date (6 June 1944) and eliminating those in units that did not see action on the day Key: R.C.I.C = Royal Canadian Infantry Corps; R.C.A.C. = Royal Canadian Armoured Corps; Sqdn. = Squadron; Coy. = Company; Regt. = Regiment; Armd. = Armoured; Amb. = Ambulance; Bn. = Battalion; Div. = Division; Bde. = Brigade; Sigs. = Signals; M.G. = Machine Gun; R.A.F. = Royal Air Force; Bty. = Battery Last Name First Name Age Rank Regiment Unit/ship/squadron Service No. Cemetery/memorial Country Additional information ADAMS MAXWELL GILDER 21 Sapper Royal Canadian Engineers 6 Field Coy. 'B/67717' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France Son of Thomas R. and Effie M. Adams, of Toronto, Ontario. ADAMS LLOYD Lieutenant 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, R.C.I.C. RANVILLE WAR CEMETERY France ADAMSON RUSSEL KENNETH 19 Rifleman Queen's Own Rifles of Canada, R.C.I.C. 'B/138767' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France Son of William and Marjorie Adamson, of Midland, Ontario. ALLMAN LEONARD RALPH 24 Flying Officer Royal Canadian Air Force 440 Sqdn. 'J/13588' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France Son of Ephraim and Annie Allman; husband of Regina Mary-Ann Allman, of Schenectady, New York State, U.S.A. AMOS HONORE Private Le Regiment de la Chaudiere, R.C.I.C. 'E/10549' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France ANDERSON JAMES K. 24 Flying Officer Royal Canadian Air Force 196 (R.A.F.) Sqdn. -

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN RANGERS, Octobre 2010

A-DH-267-000/AF-003 THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN RANGERS THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN RANGERS BADGE INSIGNE Description Description Gules a Dall ram's head in trian aspect Or all within De gueules à la tête d'un mouflon de Dall d'or an annulus Gules edged and inscribed THE ROCKY tournée de trois quarts, le tout entouré d'un anneau MOUNTAIN RANGERS in letters Or ensigned by the de gueules liséré d'or, inscrit THE ROCKY Royal Crown proper and environed by maple leaves MOUNTAIN RANGERS en lettres du même, sommé proper issuant from a scroll Gules edged and de la couronne royale au naturel et environné de inscribed with the Motto in letters Or. feuilles d'érable du même, le tout soutenu d'un listel de gueules liséré d’or et inscrit de la devise en lettres du même. Symbolism Symbolisme The maple leaves represent service to Canada and Les feuilles d'érable représentent le service au the Crown represents service to the Sovereign. The Canada, et la couronne, le service à la Souveraine. head of a ram or big horn sheep was approved for Le port de l'insigne à tête de bélier ou de mouflon wear by all independent rifle companies in the d'Amérique a été approuvé en 1899 pour toutes les Province of British Columbia in 1899. "THE ROCKY compagnies de fusiliers indépendantes de la MOUNTAIN RANGERS" is the regimental title, and Province de la Colombie-Britannique. « THE ROCKY "KLOSHE NANITCH" is the motto of the regiment, in MOUNTAIN RANGERS » est le nom du régiment, et the Chinook dialect. -

KAVANAUGH Gordon Henry

Gordon Henry KAVANAUGH Rifleman Royal Winnipeg Rifles M-8420 M-8420 Gordon Henry KAVANAUGH Personel information: Gordon Henry KAVANAUGH was born 22 December 1924 in Biggar, Saskatchewan, Canada. From the 'Soldiers Service Book' it appears that on 22 November 1943 the family KAVANAUGH was made up of father and mother, John Henry and Odile Susan, and Gordon's two sisters, Verna May and Tresa. Verna May was also in military service and as Lance Corporal, worked in the Canadian Women's Army Corps (CWAC) 103 Depot Company in Kingston, Ontario. Tresa was married to Joe Clarke. Tresa was married to Joe Clarke. Together they had four children, Kenneth aged 16, Patricia 14, Loren 12 and Michial 18 months. Tresa lived with her family in Fairfax, Alberta where they ran a farm. Gordon Henry attended the St Alphonsus Separate School and was brought up as a Roman Catholic. St. Alphonsus Separate School 1915 corner Parkstreet en Pellisser street He lived at different addresses; from his birth until he was four, in Biggar, Saskatchewan. Then the family moved to 506 Janette Avenue, Windsor, Ontario, only a short distance from the US border and Detroit. Gordon lived for a year here and after that for eight years in Toledo, Ohio, USA. Until he entered army service in 1942, Gordon lived with his sister Tresa and worked on the farm in Fairfax, Alberta. While there he also worked for about a month with the firm W.Evans as a truck driver. Gordon Henry Kavanaugh was not married and it is not known if he had a girlfriend. -

8 Th Newsletter

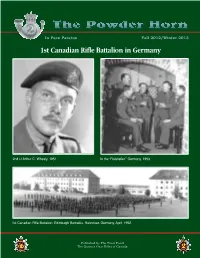

In Pace Paratus Fall 2012/Winter 2013 1st Canadian Rifle Battalion in Germany 2nd Lt Arthur C. Whealy, 1951 In the “Ratskeller,” Germany, 1953 1st Canadian Rifle Battalion, Edinburgh Barracks, Hannover, Germany, April, 1952. Published by The Trust Fund The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada 61 years ago 1st Canadian Rifle Bn sailed to Germany It has been 61 years since the 1st Canadian Rifle sonnel from rifles, line infantry or highland militia regi- Battalion sailed for foreign shores and NATO service in ments. As an independent brigade, in addition to the Germany and The Honourable Arthur C. Whealy, who infantry regiments, its complement included an died recently, was the last of eight officers from The armoured squadron, an artillery troop and contingents Queenʼs Own Rifles of Canadaʼs 1st (Reserve) Battalion from supporting services. Brigade commander was Brig who had volunteered to join the new battalion when it Geoffrey Walsh, DSO, who had served in Sicily and was formed. 57 other ranks from the reserve unit also Italy in World War Two and was awarded the joined, along with 120 new recruits. Following its forma- Distinguished Service Order for “Gallant and tion the battalion mustered at Camp Valcartier, QC, for Distinguished Services” in Sicily. six months training. In October, 1CRB paraded to the Plains of Abraham where it was inspected by Princess Upon arrival in Hannover, 1CRB and 1CHB were quar- Elizabeth during the first major tour of Canada by tered in a former German artillery housing now Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, one renamed Edinburgh Barracks. -

Jean Anderson Papers, 1894-1983

Jean Anderson Papers, 1894-1983 MSS 41 Overview Creator: Jean Anderson Title: Jean Anderson Papers Collection Number: MSS 41 Collection Dates: 1894-1983 Size: 2 boxes Accession #: 2016.69 Repository: Hanover College Archives Duggan Library 121 Scenic Drive Hanover, Indiana 47243-0287 Phone: (812) 866-7181 [email protected] Collection Information: Scope and Content Note The Jean Anderson Papers documents the life and career of Jean Anderson from 1894- 1983. The collection includes materials related to her work as a French professor at Hanover College; her father Henry Anderson; her niece Ann Steinbrecher Windle; her personal and family life; her travels to Europe; Hanover College; Indiana history; family history. Documents includes correspondence, travel diaries, and newspaper clippings. Other topics include Hanover, Indiana in the Civil War, World War I, World War II, Adolf Hitler, and the Shewsbury-Windle House. Historical Information Jean Jussen Anderson was born in Chicago, Illinois on 18 August 1887 to Henry and Anna Jussen Anderson. She worked as a professor of French at Hanover College from 1922-1952. Anderson died in Madison, Indiana on 17 December 1977. Administrative Information: Related Items: Related materials may be found by searching the Hanover College online catalog. Acquisition: Donated by Historic Madison, Inc., 2016 2/18 Jean Anderson Papers MSS 41 Property rights and Usage: This collection is the property of Hanover College. Obtaining permission to publish or redistribute any copyrighted work is the responsibility of the author and/or publisher. Preferred Citation: [identification of item], Jean Anderson Papers, MSS 41, Hanover College Finding Aid Updated: 4/19/2019 Container List Box Folder Folder Title Date Notes Jean Anderson; New York City, New York; S.S. -

Specialization and the Canadian Forces (2003)

SPECIALIZATION AND THE CANADIAN FORCES PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 40, 2003 The Norman Paterson School of International Affairs Carleton University 1125 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6 Telephone: 613-520-6655 Fax: 613-520-2889 This series is published by the Centre for Security and Defence Studies at the School and supported by a grant from the Security Defence Forum of the Department of National Defence. The views expressed in the paper do not necessarily represent the views of the School or the Department of National Defence TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 3 Introduction 4 Determinants of Force Structuring 7 Canadian Defence Policy 16 Specialization, Transformation and Canadian Defence 29 Conclusion 36 REFERENCES 38 ABOUT THE AUTHOR 40 2 ABSTRACT Canada is facing a force structuring dilemma. In spite of Ottawa’s desire to promote international peace and stability alongside the United States and the United Nations, Canada’s minimalist approaches to defence spending and capital expenditures are undermining the long-term viability of the Canadian Forces’ (CF) expeditionary and interoperable capabilities. Two solutions to this dilemma present themselves: increased defence spending or greater force structure specialization. Since Ottawa is unlikely to increase defence spending, specialization provides the only practical solution to the CF’s capabilities predicament. Though it would limit the number of tasks that the CF could perform overseas, specialization would maximize the output of current capital expenditures and preserve the CF’s interoperability with the US military in an age of defence transformation. This paper thus argues that the economics of Canadian defence necessitate a more specialized CF force structure. -

GAUTHIER John Louis

Gauthier, John Louis Private Algonquin Regiment Royal Canadian Infantry Corps C122588 John Louis Gauthier was born on Aug. 28, 1925 to French-Canadian parents, John Alfred Gauthier (1896-1983) and Clara Carriere (1900-1978) living in the Town of Renfrew, Ontario. The family also comprised James (1929-1941); Margaret (1932 died as an enfant); Blanche (1933-present) and Thomas (1937- present). Mr. Gauthier worked at the factory of the Renfrew Electric and Refrigeration Company. Jackie, as he was affectionately known, attended Roman Catholic elementary school and spent two years at Renfrew Collegiate Institute. After leaving high school, he went to work as a bench hand at the same factory as his father. In the summers, he was also a well-liked counsellor at the church youth camp in Lake Clear near Eganville, Ontario. Both his sister, Blanche, and brother, Thomas, recall Jackie’s comments when he decided to sign up for military at the age of 18 years old. “He told our mother that ‘Mom, if I don’t come back, you can walk down Main Street (in Renfrew) and hold your head high‘,” said Blanche. “In those days, men who didn’t volunteer to go overseas to war were called ‘zombies‘.” It was a common term of ridicule during the Second World War; Canadians were embroiled in debates about conscription or compulsory overseas military service. Many men had volunteered to go but others avoided enlistment. By mid-1943, the government was under pressure to force men to fight in Europe and the Far East. 1 Jackie Gauthier had enlisted on Oct. -

Edmund Fenning Parke. Lance Corporal. No. 654, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry

Great War in the Villages Project Edmund Fenning Parke . Lance Corporal. No. 654, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (Eastern Ontario Regiment.) Thirty miles from its source, the River Seven passes the village of Aberhafesp, near to the town of Newtown in the Montgomeryshire (Powys) countryside. It was here on the 20 June 1892 that Edmund Fenning Parke was born. His father, Edward, worked as an Architect and Surveyor and originated from Bidford-on-Avon, Warwickshire. His mother Harriette Elizabeth(nee Dolbey) was born in Newtown. The couple had ten children all born within the surrounding area of their mother’s home town. Edmund was the younger of their two sons. The family were living at The Pentre in Aberhafesp when Edmund was baptised on the 24 th July of the year of his birth. Within a few years the family moved to Brookside in Mochdre i again, only a short distance from Newtown. Edmund attended Newtown High School and indications are that after leaving there he worked as a clerk ii . He also spent some of his free time as a member of the 1/7 th Battalion, The Royal Welsh Fusiliers, a territorial unit based in the town iii . On the September 4 th 1910 however, Edmund set sail on the RMS Empress of Britain from Liverpool bound for a new life in Canada. The incoming passenger manifest records that he was entering Canada seeking work as a Bank Clerk. In the summer of 1914, many in Canada saw the German threat of war, in Europe, as inevitable. -

Beaumont-Hamel One Hundred Years Later in Most of Our Country, July 1St 68 Were There to Answer the Roll Call

Veterans’Veterans’ WeekWeek SSpecialpecial EditionEdition - NovemberNovember 55 toto 11, 11, 2016 2016 Beaumont-Hamel one hundred years later In most of our country, July 1st 68 were there to answer the roll call. is simply known as Canada Day. It was a blow that touched almost In Newfoundland and Labrador, every community in Newfoundland. however, it has an additional and A century later the people of the much more sombre meaning. There, province still mark it with Memorial it is also known as Memorial Day—a Day. time to remember those who have served and sacrificed in uniform. The regiment would rebuild after this tragedy and it would later earn the On this day in 1916 near the French designation “Royal Newfoundland village of Beaumont-Hamel, some Regiment” for its members’ brave 800 soldiers from the Newfoundland actions during the First World Regiment went into action on the War. Today, the now-peaceful opening day of the Battle of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Somme. The brave men advanced Memorial overlooks the old into a thick hail of enemy fire, battlefield and commemorates the instinctively tucking their chins Newfoundlanders who served in the down as if they were walking through conflict, particularly those who have a snowstorm. In less than half an no known grave. Special events were hour of fighting, the regiment would held in Canada and France to mark Affairs Canada Veterans Photo: th be torn apart. The next morning, only the 100 anniversary in July 2016. Caribou monument at the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial. Force C in The Gulf War not forgotten Against all Hong Kong Our service members played a variety of roles, from crewing odds three Canadian warships with the Coalition fleet, to flying CF-18 jet fighters in attack missions, to Photo: Department of National Department of National Photo: Defence ISC91-5253 operating a military hospital, and at Canadian Armed Forces CF-18 readying more. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

A Historiography of C Force

Canadian Military History Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 10 2015 A Historiography of C Force Tony Banham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tony Banham "A Historiography of C Force." Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015) This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : A Historiography of C Force FEATURE A Historiography of C Force TONY BANHAM Abstract: Following the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in 1941, a small number of books covering the then Colony’s war experiences were published. Although swamped by larger and more significant battles, the volume of work has expanded in the years since and is no longer insignificant. This historiography documents that body of literature, examining trends and possible future directions for further study with particular respect to the coverage of C Force. h e f a t e o f the 1,975 men and two women of C Force, sent T to Hong Kong just before the Japanese invaded, has generated a surprising volume of literature. It was fate too that a Canadian, Major General Arthur Edward Grasett, was the outgoing commander of British troops in China— including the Hong Kong garrison— in mid-1941 (being replaced that August by Major General Christopher M altby of the Indian army), and fate that his determination that the garrison be reinforced would see a Briton, Brigadier John Kelburne Lawson, arrive from Canada in November 1941 as commander of this small force sent to bolster the colony’s defences. -

Download Download

http://www.ucalgary.ca/hic • ISSN 1492-7810 2010/11 • Vol. 9, No. 1 The Americanization of the Canadian Army’s Intellectual Development, 1946-1956 Alexander Herd Abstract Canadian scholarship has detailed the impact of increasing American political, economic, and socio-cultural influences on post-Second World War Canada. This paper demonstrates that the Canadian Army was likewise influenced by the Americans, and changes to the army’s professional military education are evidence of the “Americanization” of the army. During the early Cold War period, Canadian Army staff officer education increasingly incorporated United States Army doctrine, ranging from the basic organization of American formations to complex future military strategy. Research is primarily based on the annual staff course syllabi at the Canadian Army Staff College in Kingston, Ontario, which indicate that Canadian Army leaders were sensitive not only to the realities of fighting alongside the Americans in a future war, but to the necessity of making the Canadian Army, previously historically and culturally a British army, compatible with its American counterpart. In the context of limited scholarship on the early Cold War Canadian Army, this paper advances the argument that the army’s intellectual capacity to wage war was largely determined by external influences. During the first decade after the Second World War, Canadian society underwent a distinct transition. While Canada’s various linguistic and ethnic groups — including the English-speaking majority – did not sever