From the Inside: Experiences of Prison Mental Health Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Inspection of Merseyside Comuniy Rehabilitation Company

HM Inspectorate of Probation Arolygiaeth Prawf EM An inspection of Merseyside Community Rehabilitation Company HM Inspectorate of Probation SEPTEMBER 2018 Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................. 4 Overall findings .................................................................................................... 5 Summary of ratings .............................................................................................. 8 Recommendations ................................................................................................ 9 Background ....................................................................................................... 10 Key facts ........................................................................................................... 12 1. Organisational delivery ........................................................................... 13 1.1. Leadership .......................................................................................... 14 1.2. Staff ................................................................................................... 15 1.3. Services .............................................................................................. 17 1.4. Information and facilities ...................................................................... 18 2. Case supervision ..................................................................................... 21 2.1. Assessment ........................................................................................ -

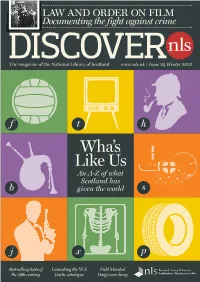

DISCOVER NLS Answer to That Question Is ‘Plenty’! Our Nation’S Issue 24 WINTER 2013 Contribution to the Rest of Mankind Is Substantial CONTACT US and Diverse

LAW AND ORDER ON FILM Documenting the fight against crime The magazine of the National Library of Scotland www.nls.uk | Issue 24 Winter 2013 f t h Wha’s Like Us An A-Z of what Scotland has b given the world s j x p Best-selling Scots of Launching the NLS Field Marshal the 19th century Gaelic catalogue Haig’s war diary WELCOME Celebrating Scotland’s global contribution What has Scotland given to the world? The quick DISCOVER NLS answer to that question is ‘plenty’! Our nation’s ISSUE 24 WINTER 2013 contribution to the rest of mankind is substantial CONTACT US and diverse. We welcome all comments, For a small country we have more than pulled our questions, submissions and subscription enquiries. weight, contributing significantly to science, economics, Please write to us at the politics, the arts, design, food and philosophy. And there National Library of Scotland address below or email are countless other examples. Our latest exhibition, [email protected] Wha’s Like Us? A Nation of Dreams and Ideas, which is covered in detail in these pages, seeks to construct FOR NLS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF an alphabetical examination of Scotland’s role in Alexandra Miller shaping the world. It’s a sometimes surprising collection EDITORIAL ADVISER Willis Pickard of exhibits and ideas, ranging from cloning to canals, from gold to Grand Theft Auto. Diversity is also at the heart of Willis Pickard’s special CONTRIBUTORS Bryan Christie, Martin article in this issue. Willis is a valued member of the Conaghan, Jackie Cromarty, Library’s Board, but will soon be standing down from that Gavin Francis, Alec Mackenzie, Nicola Marr, Alison Metcalfe, position. -

Capptive Families and Communications

CAPPTIVE Covid-19 Action Prisons Project: Tracking Innovation, Valuing Experience How prisons are responding to Covid-19 Briefing #1 Families and communications About the Prison Reform Trust The Prison Reform Trust is an independent UK charity working to create a just, humane and effective prison system. For further information about the Prison Reform Trust, see www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/ About the Prisoner Policy Network The Prisoner Policy Network is a network of prisoners, ex-prisoners and supporting organisations. It is hosted by the Prison Reform Trust and will make sure prisoners’ experiences are part of prison policy development nationally. Contact [email protected] or call 020 7251 5070 for more information. Acknowledgements Thank you to all of the people in prison that we spoke to including our PPN members who once again have gone above and beyond in making sure that not only their voices are heard in this discussion, but went out of their way to include others. We would also like to thank Pact, The New Leaf Initiative CIC, Children Heard and Seen, Our Empty Chair, Penal Reform Solutions. Thanks also goes to our PPN advisory group, friends, colleagues, and others who have offered comment on early drafts or helped to proofread before publication. © 2020 Prison Reform Trust ISBN: 978-1-908504-64-7 Cover photo credit: Erika Flowers [email protected] Printed by Conquest Litho Introduction The Covid-19 pandemic has changed the world for everyone. We have all had to give up freedoms that are precious to us. We have all been asked to do so for the sake of a common good. -

PRISON INFORMATION BULLETIN Page 13 and 14/89 Foreword

ISSN 0254-5225 COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L'EUROPE Prison Informati on Bulletin No. 13 and 14 - JUNE and DECEMBER 1989 CONTENTS PRISON INFORMATION BULLETIN Page 13 and 14/89 Foreword ....................................................................... 3 Published twice yearly in French and English, by the Council Education in Prisons ... :.......................................... 4 of Europe Introduction ..................................................................... 4 Strengthening prison education .................................... 4 Reproduction Articles or extracts may be reproduced on condition that the Equal status and payment for education .................... 4 source is mentioned. A copy should be sent to the Chief The participants and motivation .................................. 5 Editor. A degree of autonomy for the education sector.......... 5 The right to reproduce the cover illustration is reserved. An adult education approach ........................................ 6 A change in emphasis ................................................... 6 Correspondence Learning opportunities ................................................... 8 All correspondence should be addressed to the Directorate of Legal Affairs, Division of Crime Problems, Creative activities ........................................................... 9 Council of Europe, 67006 Strasbourg, Cedex Social education ............................................................. 9 France Interaction with the community ................................... -

December 2015

20 Mr Cameron, 25 Formal complaints 35 In Prison there ought to be more the prisoners’ prerogative Permanently the National Newspaper for Prisoners & Detainees old lags in Whitehall How to make a formal The politics of the IPP Plans to revolutionise complaint the right way sentence by Geir Madland a voice for prisoners 1990 - 2015 jails so prisoners leave by Paul Sullivan A ‘not for profit’ publication / ISSN 1743-7342 / Issue No. 198 / December 2015 / www.insidetime.org rehabilitated and ready for Seasons greetings to all our readers An average of 60,000 copies distributed monthly Independently verified by the Audit Bureau of Circulations work by Jonathan Aitken POA Gives NOMS 28 DAYS to put its House in Order Eric McGraw TEN MOST OVERCROWDED PRISONS at the end of October 2015 n a letter to Michael Spurr, Chief Prison Designed Actually Executive of the National Offender Man- to hold holds agement Service (NOMS), the Prison Officers’ Association (POA) has issued a Kennet 175 317 28-day notice requiring NOMS ‘to Leeds 669 1,166 Iaddress a number of unlawful and widespread Wandsworth 943 1,577 practices which exacerbate the parlous health and safety situation’ in prisons in England and Swansea 271 442 Wales. Failure to do so, they warn, will lead to Exeter 318 511 ‘appropriate legal action’. Durham 595 928 Leicester 214 331 The letter, dated November 11, 2015, states Preston 455 695 that the prison service does not have enough staff to operate safely. This, says the POA, has Brixton 528 802 been caused by a ‘disastrously miscalculated’ Lincoln 403 611 redundancy plan devised by the Government which has reduced the number of staff on the ‘mistaken assumption’ that prison numbers would fall: in fact, as everyone knows, they their ‘Certified Normal Accommodation’ by have risen. -

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom How it Happened and Why it Still Matters Julian B. Knowles QC Acknowledgements This monograph was made possible by grants awarded to The Death Penalty Project from the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Sigrid Rausing Trust, the Oak Foundation, the Open Society Foundation, Simons Muirhead & Burton and the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture. Dedication The author would like to dedicate this monograph to Scott W. Braden, in respectful recognition of his life’s work on behalf of the condemned in the United States. © 2015 Julian B. Knowles QC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Copies of this monograph may be obtained from: The Death Penalty Project 8/9 Frith Street Soho London W1D 3JB or via our website: www.deathpenaltyproject.org ISBN: 978-0-9576785-6-9 Cover image: Anti-death penalty demonstrators in the UK in 1959. MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY 2 Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................5 A brief -

House of Lords

Session 2017-19 Wednesday No. 56 24 January 2018 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS WRITTEN STATEMENTS AND WRITTEN ANSWERS Written Statements ................................ ................ 1 Written Answers ................................ ..................... 2 [I] indicates that the member concerned has a relevant registered interest. The full register of interests can be found at http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords-interests/ Members who want a printed copy of Written Answers and Written Statements should notify the Printed Paper Office. This printed edition is a reproduction of the original text of Answers and Statements, which can be found on the internet at http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/. Ministers and others who make Statements or answer Questions are referred to only by name, not their ministerial or other title. The current list of ministerial and other responsibilities is as follows. Minister Responsibilities Baroness Evans of Bowes Park Leader of the House of Lords and Lord Privy Seal Earl Howe Minister of State, Ministry of Defence and Deputy Leader of the House of Lords Lord Agnew of Oulton Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Department for Education Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office Lord Ashton of Hyde Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Lord Bates Minister of State, Department for International Development Lord Bourne of Aberystwyth Parliamentary -

Quality of Employment in Prisons

Quality employment and quality public services Quality of employment in prisons Country report: Britain Lewis Emery, Labour Research Department The production of this report has been financially supported by the European Union. The European Union is not responsible for any use made of the information contained in this publication. This report is part of a project, Quality Employment and Quality Public Services, run by the European Federation of Public Services with research coordinated by HIVA Project management: Monique Ramioul Project researcher: Yennef Vereycken KU Leuven HIVA RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR WORK AND SOCIETY Parkstraat 47 box 5300, 3000 LEUVEN, Belgium [email protected] http://hiva.kuleuven.be Q uality of employment in prisons | 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Acknowledging the problems ....................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Birmingham and other “incidents” ............................................................................................... 9 1.3 Short-term responses, longer-term reform ............................................................................... -

Report to the United Kingdom Government on the Visit to The

CPT/Inf (96) 11 Report to the United Kingdom Government on the visit to the United Kingdom carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 15 to 31 May 1994 The United Kingdom Government has requested the publication of this report and of it's final response. The Government's final response is set out in document CPT/Inf (96) 12. Strasbourg, 5 March 1996 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page COPY OF THE LETTER TRANSMITTING THE CPT'S REPORT .........................................7 I. INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................7 A. Dates of the visit and composition of the delegation ..............................................................8 B. Establishments visited...............................................................................................................9 C. Consultations held by the delegation.....................................................................................10 D. Co-operation encountered during the visit...........................................................................10 E. Immediate observations under Article 8 (5) of the Convention..........................................13 II. FACTS FOUND DURING THE VISIT TO ENGLAND AND ACTION PROPOSED...13 A. Police establishments ..............................................................................................................14 1. Introduction .....................................................................................................................14 -

Independent Inquiry Into the Care and Treatment of David Johnson

Independent Inquiry into the Care and Treatment of David Johnson Commissioned by Birmingham Health Authority Mr T McGowran chairman Mrs J Mackay Mrs L Mason Dr O Oyebode Index Inquiry Team Members Acknowledgements Chapter 1 Introduction Chapter 2 Social circumstances and contact with mental health services prior to 1996 Chapter 3 Contact with mental health services in Birmingham 1996- 97 Chapter 4 Inquiry findings Chapter 5 Conclusions Chapter 6 Recommendations Appendices 2 INQUIRY TEAM MEMBERS Mr Terry McGowran Solicitor and Chairman of the Inquiry Mrs Jane Mackay Nursing and Management Consultant Mrs Lotte Mason Senior Social Work Consultant Dr Oyedeji Oyebode Clinical Director, Consultant and Honorary Senior Lecturer in Forensic Psychiatry 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We should like to thank everyone who gave evidence and who spoke so freely to us which made our task easier despite the time lapse between the tragic incident and the inquiry. We were sorry not to be in a position of extending our condolences to the family of Geraldine Simpson. We are also indebted to Fiona Shipley and her colleagues for the efficient way in which they recorded and transcribed the evidence for us. We would also like to extend our gratitude to the staff of Birmingham Health Authority for looking after all our needs whilst we took evidence. Finally, the chairman would also like to extend his gratitude to Jane Mackay who not only served as an Inquiry Team member but also acted as our co-ordinator and whose organisational skills made light of the complex arrangements that are required in the establishment and management of an inquiry such as this. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Whole Life Order Its genesis; the challenges it both poses and faces; and its uncertain future Grainger, Katherine Jane Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 The Whole Life Order: its genesis; the challenges it both poses and faces; and its uncertain future Katherine J Grainger The Dickson Poon School of Law King’s College University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy 1 ABSTRACT The whole life order was introduced in the Criminal Justice Act 2003 as the most severe penalty available to the judiciary in England and Wales. -

Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood

CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD St. James's Palace, London SW1 14 June 2008 The QUEEN has been graciously pleased, on the occasion of the Celebration of Her Majesty's Birthday, to signify her intention of conferring the honour of Knighthood upon the undermentioned: Knights Bachelor Dr. James Iain Walker ANDERSON, C.B.E. For public and voluntary service. William Samuel ATKINSON, Headteacher, Phoenix High School, Hammersmith and Fulham, London. For services to Education and to Community Relations. The Right Honourable Alan James BEITH, M.P., Member of Parliament for Berwick-upon- Tweed. For services to Parliament. Professor James Drummond BONE, F.R.S.E., Vice-Chancellor, University of Liverpool. For services to Higher Education and to Regeneration in the North West. Professor Christopher Richard Watkin EDWARDS. For services to Higher Education, Medical Science and to Regeneration in the North East. Mark Philip ELDER, C.B.E., Conductor and Music Director, Halle« Orchestra. For services to Music. Leonard Raymond FENWICK, C.B.E., Chief Executive, Newcastle-upon-Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. For services to Healthcare and to the community in Tyne and Wear. Dr. Philip John HUNTER, C.B.E., Chief Schools Adjudicator. For services to Education. Moir LOCKHEAD, O.B.E., Chief Executive, First Group. For services to Transport. Professor Andrew James MCMICHAEL, F.R.S., Professor of Molecular Medicine and Director, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford. For services to Medical Science. William MOORCROFT, Principal, Trafford College. For services to local and national Further Education. William Desmond SARGENT, C.B.E., Executive Chair, Better Regulation Executive, Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform.