Chicana Punk Rock in East Los Angeles: Creating a New Transnational Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-011534Lbr

Legacy Business Registry Executive Summary HEARING DATE: JANUARY 6, 2021 Filing Date: December 9, 2020 Case No.: 2020-011534LBR Business Name: 24th Street Dental Business Address: 2720 24th St Zoning: NCT - 24th-Mission Neighborhood Commercial Transit Calle 24 SUD 65-X Block/Lot: 4211/016 Applicant: Dr. Bernardo D. Gonzalez III 2720 24th Street, San Francisco, CA 94110 Nominated By: Supervisor Hillary Ronen Located In: District 9 Staff Contact: Kalyani Agnihotri – (628)652-7454 [email protected] Recommendation: Adopt a Resolution to Recommend Approval Business Description 24th Street Dental is a dental practice owned by Dr. Bernardo D. Gonzalez III, located at 2720 24th Street in the Mission District. The address’ history dates back to before the dental practice was established in 1985 when it was the location of the shoe store owned by Dr. Gonzalez’s father. Dr. Gonzalez, a fixture of the city’s local music scene, came to be known as “Dr. Rock,” when he served as manager of the pioneering Latin rock group Malo and organized the annual benefit “Voices of Latin Rock” for 10 years. While concurrently running his dental practice, Dr. Rock has continually been involved in significant Mission cultural activities. In 1981, Dr. Rock helped produce the 24th Street Fair for the 24th Street Merchants Association, and subsequently became their president. After his successes with the 24th St. Merchants Association, Dr. Rock created the Mission Economic Cultural Association, or MECA along with Roberto Hernandez, which produced the 24th Street Fair, Cinco de Mayo, and Legacy Business Registry 2020-011534 LBR January 6, 2021 Hearing 24th Street Dental Carnaval. -

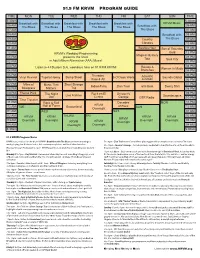

Vertical Program Guide CW 9

91.9 FM KRVM PROGRAM GUIDE TIME MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN TIME 5:30am 5:30am Breakfast with Breakfast with Breakfast with Breakfast with Breakfast with KRVM Music 06 AM 06 AM The Blues The Blues The Blues The Blues The Blues Breakfast with 07 AM The Blues 07 AM 08 AM Breakfast with 08 AM 09 AM Country The Blues 09 AM 10 AM Classics 10 AM 11 AM Beatles Hour Son of Saturday 11 AM 12 PM KRVM’s Weekday Programming Gold 12 PM Magical Mystery 01 PM presents the finest 01 PM Tour Soul City 02 PM in Adult Album Alternative (AAA) Music! 02 PM 03 PM 03 PM Listen to 4J Student DJs, weekdays here on 91.9 FM KRVM! Routes & Women in Music 04 PM Branches 04 PM 05 PM Thursday 05 PM Vinyl Revival Tupelo Honey Bump Skool 5 O’Clock World Acoustic Sounds Global 06 PM Free 4 All Junction 06 PM 07 PM Miles of Music That Short Strange 07 PM Indian Time Zion Train 60s Beat Swing Shift 08 PM Bluegrass Matters Trip 08 PM 09 PM Theme Park The Night Rock en El Greaser’s 09 PM Live Archive Soundscapes 10 PM Owl Centro Garage GTR Radio 10 PM Time Traveler 11 PM Rock & Roll Decades MON 11 PM KRVM 12 AM TUE Hall of Fame Grooveland of Rock SUN 12 AM Overnight 01 AM WED SAT 01 AM 02 AM KRVM KRVM THURS FRI KRVM KRVM 02 AM KRVM 03 AM Overnight Overnight Overnight Overnight 03 AM KRVM KRVM Overnight 04 AM Overnight Overnight 04 AM 5:30am 5:30am 91.9 KRVM Program Notes KRVM is your station for the blues! KRVM's Breakfast with The Blues airs seven mornings a 7 to 9pm - Zion Train hosts Corey & Pete play reggae with an emphasis on conscious 70s roots. -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilkins, Rex Richard, "El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 6997. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6997 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brian Price, Chair Erik Larson Alvin Sherman Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Rex Richard Wilkins All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Department of Spanish and Portuguese, BYU Master of Arts This thesis examines the punk genre’s evolution into commercial mainstream music in Spain and Mexico. It looks at how this evolution altered both the aesthetic and gesture of the genre. This evolution can be seen by examining four bands that followed similar musical and commercial trajectories. -

RAW POWER · Llletal Lllachine Lllagazine NO.I

------4~. ~-- --~-·- .__,....-. ____ 25¢ RAW POWER · llletal lllachine lllagazine NO.I CHEAP TRICK ANGEL DAMNED DOGS WEIRDOS concert and albulll revte".,.s• upcoming concerts RAW POWER CONTENTS iCheap Trick •••••. 3 STAFF :Getting More for Your Money . 3 Quick Draw 'Saturday's Party Place 4 & ; Angel • . • • 5 Bobalouie (Punk Theater 6 •concert Review 7 (We Do Everything) 'The Damned 8 :Rodney on the Rocks 9 Special thanks to: ·Album Reviews . 9 Jim Davidson . 10 & :upcoming Concerts . • 10 Linda Hartman I N F 0 Send all letters and mail to: Quick Draw Our ads are cheap 23938 Mariano Phone: 888-7205 Woodland Hills, CA 91364 Q.D. BOBALOUIE i i GETTING MORE l CHEAP TRICK FOR YOUR MONEY '-~y Quick Draw By Bobalouie Rick Nielsen, Cheap Trick's lead : All you suckers out there who guitarist, owns 35 guitars and wait overnight or get up at dawn to probably a million guitar picks. go down and buy concert tickets are During a Cheap Trick concert, Rick really showing your mentality ... flicks almost 50 picks into the Zero; you guys are so dumb. There crowd. Sitting third row at a are ten ways you can get great recent show, I gathered several of seats and pay the cheapest prices, his picks myself. I was amazed at just by reading this article. Rick's stage antics. He hops all 1. Lay a bouncer on to a twenty over the stage, bug-eyed with an or try to get to be good friends ever-changing weird face. Chord with him. slamming clean and sharp. The 2. -

Download Internet Service Channel Lineup

INTERNET CHANNEL GUIDE DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 28 Adult Alternative Adult Alternative 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 30 Eclectic Rock Eclectic Rock 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 32 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 68 New Age New Age 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative Grunge and ’90s Alternative Rock 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock Alt Rock 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 704 ’70s/’80s Pop ’70s & ’80s Super Party Hits 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Rock 49 Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 705 ’80s/’90s Pop ’80s & ’90s Party Hits 15 Pop Mix Modern Pop Mix Modern 51 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Pop Mix Bright 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 56 New Country Today’s New Country 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend POP HIP-HOP 750 Cinemagic Movie Soundtracks & More 751 Krishna Das Yoga Radio Chant/Sacred/Spiritual Music 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 43 Backspin Classic Hip-Hop XL 782 Holiday Traditions Traditional Holiday Music -

Geschiedenis Van De Rockmuziek Gratis Epub, Ebook

GESCHIEDENIS VAN DE ROCKMUZIEK GRATIS Auteur: David Roberts Aantal pagina's: 576 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2013-08-01 Uitgever: Librero Nederland B.V. EAN: 9789089983251 Taal: nl Link: Download hier De geschiedenis van de rockmuziek Zo kun je meteen zien welke muzikanten wanneer meespeelden en op welke instrumenten, bij welke platenlabels de band zat, wanneer de albums uitkwamen en wie daarop meespeelden. Bovendien zie je de verkoopcijfers van de succesvolste albums van topbands. Van meer dan vijftig van de belangrijkste bands is de beschrijving aangevuld met een dubbele fotopagina, die een schitterend overzicht geeft van de veranderingen in hun uiterlijk, gekoppeld aan hun beste albums en historische hoogtepunten. Achter in het boek staat een uitgebreid artiestenregister. Hierin staan alle beschreven muzikanten vermeld, zodat je de rockcarrière van de afzonderlijke bandleden kunt volgen van de ene band naar de andere, en weer terug. Boeiend, uitgebreid en boordevol informatie: Geschiedenis van de rockmuziek is hét naslagwerk voor iedereen die van rock houdt. Bekijk ook eens deze boeken. Vinyl Mike Evans. Jimi Hendrix Gillian G. Na Curtis' dood bracht de band nog Closer uit, het tweede en laatste album. De overige bandleden creëerden een nieuwe band: New Order. Een nieuwe stroming bands in de jaren 80 werd onder de noemer " alternatieve rock " geschaard, die gebruikt werd om punkrockgeïnspireerde bands te beschrijven die niet in de mainstreammuziek pasten. Een van de eerste albums die tot de alternatieve rock werden gerekend, was Murmur , het debuut van de Amerikaanse band R. Deze band werd eind jaren 80 een gevestigde naam, met albums als Out of Time en Automatic for the People. -

Rock Music and Representation: the Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311S // Unique No

Page 1 Rock Music and Representation: The Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311s // Unique No. 31080 Spring 2020 BUR 436A: M/W/F 11:00 am – 12:00 pm Instructor: Kate Grover // [email protected] // pronouns: she, her, hers Office Hours: BUR 408 // Monday & Wednesday, 1 pm – 2:30 pm, or by appointment Course Description What is a guitar god? Who gets to be one, and why? What are the “roles” of rock music and culture? What is rock, anyway? This is not your average rock history course. Instead, this course positions 20th and 21st century American rock music and culture as a crucial site for ongoing struggles over identity, belonging, and power. We will explore how race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability have shaped how various groups of people engage with rock and what insights these engagements provide about “the American experience” over time. How do rock artists, critics, filmmakers, and fans represent themselves and others? What do these representational strategies reveal about inclusion and exclusion in rock culture, and in American society at large? While examining rock’s players, we will also consider the roles of different rock media and institutions such as MTV, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and Rolling Stone magazine. As such, our course is divided into three units exploring different areas of representation within rock music and culture. Unit 1: Performing Rock, Performing Identity, provides an introduction to studying rock’s sounds, visuals, and texts by investigating various issues of identity within rock music and culture. Unit 2: Evaluating Rock: Writers, Critics, and Other Commentators focuses on the roles of rock critics and the stakes of writing about music. -

Punk Is Dead” Catalog Includes, the SST Records the Inventory Representing the “Punk Is Collection, C

2016 PUNK IS DEAD Lux Mentis, Booksellers Lux Mentis Booksellers specializes in fine press, artist books, first editions, Punk rock evolved over several and esoterica with a particular emphasis generations and manifestations of youth on challenging and unusual materials. culture beginning in the 1970s. Even after 40 years, punk subculture still We actively collaborate with archives demonstrates the capability to influence and special collections libraries to meet successive contemporary elements of the research and collecting needs of art, music, and fashion regardless of its public learning institutions, private, original intention to lambast conformity. independent libraries and collections with primary sources. Selected inventory in the “Punk is Dead” catalog includes, the SST Records The inventory representing the “Punk is Collection, c. 1979-1996; original Dead” collection is a retrospective artwork from famed punk artist, selection of critical primary source Raymond Pettibon; correspondence materials documenting the punk rock from Gordon Gano, original member of movement of the 1970s-1990s. The the Violent Femmes; and several unique collection illustrates the profound fanzine and alternative publications. subculture of punk from an artistic and politically fueled era from Los Angeles, Lux Mentis regularly features and New York, and London. showcases punk culture related materials at major ABAA book fairs and Please contact us for an appointment or continues to cultivate the acquisition of with questions regarding the inventory. subculture materials for research and collection development purposes. 110 Marginal Way #777 Portland, ME 04101 Member: ILAB/ABAA T. 207.329.1469 Email: [email protected] Front cover image: From the SST [email protected] Records Collection, detail of “Outcry” Web: http://www.luxmentis.com magazine Blog: http://www.asideofbooks.com Cataloged created by Kim Schwenk and edited by Ian Kahn 2 Ginn, Greg, Pettibon, Raymond, et al. -

Dawn Wirth Punk Ephemera Collection LSC.2377

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8tq67pb No online items Finding aid for the Dawn Wirth punk ephemera collection LSC.2377 Finding aid prepared by Kelly Besser, 2020. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2020 May 12. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding aid for the Dawn Wirth LSC.2377 1 punk ephemera collection LSC.2377 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Dawn Wirth punk ephemera collection Creator: Wirth, Dawn, 1960- Identifier/Call Number: LSC.2377 Physical Description: .2 Linear Feet(1 box) Date (inclusive): 1977-2008, bulk 1977-1978 Abstract: Dawn Wirth bought her first camera in 1976, a Canon FTb, with the money she earned from working at the Hanna-Barbera animation studio. She enrolled in a high-school photography class and began taking photos of bands. While still in high school, Wirth captured on film, the beginnings of an underground LA punk scene. She photographed bands such as The Germs, The Screamers, The Bags, The Mumps, The Zeros and The Weirdos in and around The Masque and The Whiskey a Go-Go in Hollywood, California. The day of her high school graduation, Wirth took all of her savings and flew to the United Kingdom where she lived for the next six months and took color photographs of The Clash before they came to America. Dawn Wirth's photographs have been seen in the pages of fanzines such as Flipside, Sniffin' Glue and Gen X and featured in the Vexing: Female Voices from East LA Punk exhibition at Claremont Museum of Art and at DRKRM. -

EASTSIDE PUNKS a Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 P.M

THEMEGUIDE EASTSIDE PUNKS A Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 p.m. Live via Zoom University of Southern California WHAT TO KNOW o Eastside Punks is a series of documentary shorts produced by Razorcake magazine about the first generation of East L.A. punk, circa the late 1970s and early ’80s o This event includes excerpts from Eastside Punks and a panel discussion with members of several of the featured bands: Thee Undertakers, The Brat, and the Stains o Razorcake is an L.A.-based DIY punk zine Photo: Angie Garcia ABOUT THE PARTICIPANTS Jimmy Alvarado (Eastside Punks director) has been active in East L.A.’s underground music scene since 1981 as a musician, backyard gig promoter, writer, poet, bouncer, flyer artist, photographer, podcaster, historian, and filmmaker. He has authored numerous interviews, articles, and short films spotlighting the Eastside scene. He plays guitar in the bands La Tuya and Our Band Sucks. Teresa Covarrubias was the vocalist for The Brat. Their debut EP, Attitudes, was released on The Plugz’ record label, featured contributions from John Doe and Exene from X, and is a prized item among collectors. Straight Outta East L.A., a double Photo: Edward Colver album packaging it with other rare tracks, was released in 2017. Tracy “Skull” Garcia was the bass player of Thee Undertakers. Starting off by playing local parties in 1977, they became regulars in the scene centered around the Vex. Their 1981 debut album, Crucify Me, successfully melded second-wave hardcore bite with first-wave art sensibilities, but wasn’t released until 2001 on CD and 2020 on vinyl. -

Violence Girl East LA Rage to Hollywood Stage, a Chicana Punk

VIOLENCE GIRL EAST L. A. RAGE TO HOLLYWOOD STAGE, A CHICANA PUNK STORY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Alice Bag | 9781936239122 | | | | | Violence Girl: East L.A. Rage to Hollywood Stage, a Chicana Punk Story Details if other :. This was fluffy until it wasn't, and a Chicana Punk Story 1st edition longer it went on, the more it broke my heart. Her frankness about her feelings towards her father, who was an abusive man, but still loved her was a refreshing change to the usual approach to this subject matter. Violence Girl takes us from a violent upbringing to an aggressive punk sensibility; this time a difficult coming-of-age memoir culminates with a satisfying conclusion, complete with a happy marriage and children. The writing style reminded me a lot of YA which is not a criticism since I've written YA because of the strong voice of the character. Thank you! Alice Bag. Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. Pricing policy About our prices. Average Rating: 4. Beg, borrow or steal this book by all means. Nearly a hundred excellent photographs energize the text in remarkable ways. In that sense, this is a DIY punk book! I highly recommend this book to anyone, fan of punk, or fan of narrative history, or just maybe curious about this era of Los Angeles. Alice's life growing up in East L. Friend Reviews. Biography Memoir. A discursive book written in short chapters, "Violence Girl" is a quick read, even though it's more than pages long.