Oldham and Rochdale: Race, Housing and Community Cohesion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heywood Distribution Park OL10 2TT, Greater Manchester

Heywood Distribution Park OL10 2TT, Greater Manchester TO LET - 148,856 SQ FT New self-contained production /distribution unit Award winning 24 hour on-site security, CCTV and gatehouse entry 60m service yard 11 dock and two drive in loading doors 1 mile from M66/J3 4 miles from M62/J18 www.heywoodpoint.co.uk Occupiers include: KUEHNE+NAGEL DPD Group Wincanton K&N DFS M66 / M62 Fowler Welch Krispy Kreme Footasylum Eddie Stobart Paul Hartmann 148,000 sq ft Argos AVAILABLE NOW Main Aramex Entrance Moran Logistics Iron Mountain 60m 11 DOCK LEVELLERS LEVEL ACCESS LEVEL ACCESS 148,856 sq ft self-contained distribution building Schedule of accommodation TWO STOREY OFFICES STOREY TWO Warehouse 13,080 sq m 140,790 sq ft Ground floor offices 375 sq m 4,033 sq ft 90.56m First floor offices 375 sq m 4,033 sq ft 148,000 sq ft Total 13,830 sq m 148,856 sq ft SPACES PARKING 135 CAR 147.65m Warehouse Offices External Areas 5 DOCK LEVELLERS 50m BREEAM “very good” 11 dock level access doors Fully finished to Cat A standard LEVEL ACCESS 60m service yardLEVEL ACCESS EPC “A” rating 2 level access doors 8 person lift 135 dedicated car parking spaces 12m clear height 745kVA electricity supply Heating and comfort cooling Covered cycle racks 50kN/sqm floor loading 15% roof lights 85.12m 72.81m TWO STOREY OFFICES 61 CAR PARKING SPACES M66 Rochdale Location maps Bury A58 Bolton A58 M62 A56 A666 South Heywood link road This will involve the construction of a new 1km road between the motorway junction and A58 M61 Oldham A new link road is proposed which will Hareshill Road, together with the widening M60 A576 M60 provide a direct link between Heywood and upgrading of Hareshill Road. -

Oldham School Nursing Clinical Manager Kay Thomas Based At

Oldham School Nursing Clinical Manager Kay Thomas based at Stockbrook Children’s Centre In the grounds of St Luke’s CofE Primary School Albion Street Chadderton Oldham OL9 9HT 0161 470 4304 School Nursing Team Leader Suzanne Ferguson based at Medlock Vale Children’s Centre The Honeywell Centre Hadfield Street Hathershaw Oldham, OL8 3BP 0161 470 4230 Email: [email protected] Below is a list of schools with the location and telephone number of your child’s School Nurse School – East Oldham / Saddleworth and Lees Beever Primary East / Saddleworth and Lees School Clarksfield Primary Nursing team Christ Church CofE (Denshaw) Primary Based at; Delph Primary Diggle School Beever Children's Centre Friezland Primary In the grounds of Beever Primary Glodwick Infants School Greenacres Primary Moorby St Greenfield Primary Oldham, OL1 3QU Greenhill Academy Harmony Trust Hey with Zion VC Primary T: 0161 470 4324 Hodge Clough Primary Holy Cross CofE Primary Holy Trinity CofE (Dobcross) School Horton Mill Community Primary Knowsley Junior School Littlemoor Primary Mayfield Primary Roundthorn Primary Academy Saddleworth School St Agnes CofE Primary St Anne’s RC (Greenacres) Primary St Anne’s CofE (Lydgate) Primary St Chads Academy St Edward’s RC Primary St Mary’s CofE Primary St Theresa’s RC Primary St Thomas’s CofE Primary (Leesfield) St Thomas’s CofE Primary (Moorside) Springhead Infants Willow Park The Blue Coat CofE Secondary School Waterhead Academy Woodlands Primary Oldham 6th form college Kingsland -

My Lifestory by Audrey Pettigrew Family Life

My Lifestory by Audrey Pettigrew Family Life I was born on 21st August 1932 at St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester. 2 The only photo taken of me as a baby is the one below, when I was 12 months old. Before I was born my mother gave birth to unnamed, stillborn, twin boys. 3 My mother was Margaret Evans and my father was Arthur Gregory. My dad served in World War I. A soldier’s tin hat, WWI Dad when he was in the army 4 After the war he became an engineer at Platts, Oldham. The headquarters of Platts 5 As a young woman my mum worked in cotton mills. Later she went into Service working for a family of Dutch Jews, who had fled to the U.K. to escape the Nazis in their homeland. The holocaust badge. The word Jew is written in Dutch. 6 The Dutch family became very instrumental in my upbringing, and became lifelong friends. Mum would take me to work with her where I met Jan, a Dutch boy. As youngsters we played happily together, and in our teens we spent many happy times in Holland. 7 I lived in Cranberry Street, Glodwick, Oldham, quite a poor neighbourhood. I lived in a two up two down terraced house with no bathroom. When I was 8 years old in 1940, I witnessed a bomb exploding in my street and destroying houses and the local pub, the Cranberry Inn. 8 My mother had several sisters who lived nearby. I affectionately knew them as the “old aunts” and they took turns at looking after me, whilst my mother worked. -

Jewson Civils

Page 1 JEWSON CIVILS Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Page 2 Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Jewson Civils, Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX INVESTMENT SUMMARY Opportunity to acquire a single let trade counter unit with secure open storage and loading yard. The accommodation totals 43,173 sq ft (4,011 sq m) and benefits from 40 customer parking spaces; Site area of 3.12 acres (1.27 ha) with a low site coverage of 33%; Let to Jewson Ltd (guaranteed by Saint-Gobain Building Distribution Limited) for a term of 15 years from 3 July 2007 (expiring 2 July 2022), providing 2.75 years term certain; A low current passing rent of £213,324 per annum, reflecting only £4.94 per sq ft. Saint-Gobain Building Distribution Limited has a D&B rating of 5A2, representing a minimum risk of business failure; Long Leasehold (808 years unexpired); Offers are sought in excess of £2,855,000 (Two Million, Eight Hundred and Fifty Five Thousand Pounds), subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. A purchase at this level reflects an attractive net initial yield of 7.00% and a capital value of £66 per sq ft (assuming purchaser’s costs of 6.43%). Page 3 Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Jewson Civils, Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX LOCATION Oldham is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, one of the ten boroughs that comprise Greater Manchester conurbation and a major administrative and commercial centre. The town lies approximately 8 miles north east of Manchester City Centre via the A62 (Oldham Road), 4 miles north of Ashton-under-Lyne via A627 (Ashton Road) and 6 miles south of Rochdale via the A671 (Oldham Road). -

Oldham District Budget Report

Report to Oldham District Executive Oldham District Budget Report Portfolio Holder: Cllr B Brownridge, Cabinet Member for Cooperatives & Neighbourhoods Officer Contact: Helen Lockwood, Executive Director, Cooperatives & Neighbourhoods Report Author: Simon Shuttleworth; District Coordinator, Oldham Ext. 4720 27th January 2016 Reason for report To advise the Oldham District Executive of the current budget position and seek approval for proposed items of spend. Recommendations 1. To note the current budget position 2. To make the following budget allocations (revenue, unless stated otherwise): a) Winterbottom Street Bollards £2,700 Capital b) Millennium Green/Sholver Centre £3,000 Capital c) Works to Stoneleigh Park £2,500 Capital d) Crèche for Mindfulness Course £720 e) Football provision at Broadfield School pitch £2,658 f) Waste and litter project £7,126 g) Highways Improvements £20,000 Capital h) Alleygating – Glodwick £2,000 Capital i) Clarksfield Alleyway Initiative £4,300 j) Arundel Street Park £2,000 Capital k) Stoneleigh Park Cabin pool table - £291 Revenue Oldham District Executive 27th January 2016 Oldham District Budget Report 1 Background 1.1 The Oldham District Executive has been assigned the below budget for 2015/2016: Revenue 2015/2016 Capital 2015/2016 Alexandra £10,000 £10,000 Coldhurst £10,000 £10,000 Medlock Vale £10,000 £10,000 St James’ £10,000 £10,000 St Mary’s £10,000 £10,000 Waterhead £10,000 £10,000 Werneth £10,000 £10,000 1.2 Each Councillor also has an individual budget of £5000 for 2015/2016 Allocations to date are shown in the attached Appendix 1 2 Current Position 2.1 Revenue and Capital Budgets Allocations made so far are shown below. -

The Royal Oldham Hospital, OL1

The Royal Oldham Hospital, OL1 2JH Travel Choices Information – Patient and Visitor Version Details Notes and Links Site Map Site Map – Link to Pennine Acute website Bus Stops, Services Bus Stops are located on the roads alongside the hospital site and are letter and operators coded. The main bus stops are on Rochdale Road and main bus service is the 409 linking Rochdale, Oldham and Ashton under Lyne. Also, see further Bus Operators serving the hospital are; information First Greater Manchester or on Twitter following. Rosso Bus Stagecoach Manchester or on Twitter The Transport Authority and main source of transport information is; TfGM or on Twitter ; TfGM Bus Route Explorer (for direct bus routes); North West Public Transport Journey Planner Nearest Metrolink The nearest stops are at Oldham King Street or Westwood; Tram Stops Operator website, Metrolink or on Twitter Transport Ticketing Try the First mobile ticketing app for smartphones, register and buy daily, weekly, monthly or 10 trip bus tickets on your phone, click here for details. For all bus operator, tram and train tickets, visit www.systemonetravelcards.co.uk. Local Link – Users need to be registered in advance (online or by phone) and live within Demand Responsive the area of service operation. It can be a minimum of 2 hours from Door to Door registering to booking a journey. Check details for each relevant service transport (see leaflet files on website, split by borough). Local Link – Door to Door Transport (Hollinwood, Coppice & Werneth) Ring and Ride Door to door transport for those who find using conventional public transport difficult. -

Roadworks-Bulletin-8-June

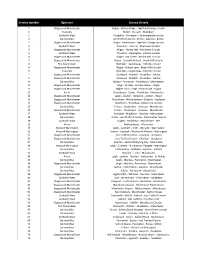

Roadworks and Closures expected expected restriction contractor reason Location start finish OLDHAM WAY,OLDHAM LANE CLOSURE Monday Friday Oldham New highway (From Prince Street To Lees Road) 30/03/2020 26/06/2020 (01617705116) installation works YORKSHIRE STREET,OLDHAM LANE CLOSURE Monday Friday Oldham Highway Authority (Between Rhodes Bank And Union Street) 30/03/2020 26/06/2020 (01617705116) Works UNION STREET,OLDHAM LANE CLOSURE Monday Friday Oldham Highway Authority (From Rhodes Bank To Prince Street) 30/03/2020 26/06/2020 (01617705116) Works PRINCE STREET,OLDHAM LANE CLOSURE Monday Friday Oldham Highway Authority (Oldham Way To Union Street) 30/03/2020 26/06/2020 (01617705116) Works ABBEY HILLS ROAD,OLDHAM MULTI-WAY SIGNALS Monday Monday Oldham Highway Authority (Junction Of Lees New Road) 01/06/2020 08/06/2020 (0617704140) Works LEES NEW ROAD,OLDHAM MULTI-WAY SIGNALS Monday Monday Oldham Highway Authority (For A Distance Of 70M From Abbey Hills Road 01/06/2020 08/06/2020 (0617704140) Works In Each Dirction) MANCHESTER ROAD,OLDHAM LANE CLOSURE Thursday Wednesday Electricity North Works (Adj 459 Manchesterr Road) 11/06/2020 17/06/2020 West (0843 3113377 Streetw) MIDDLETON ROAD,CHADDERTON TWO-WAY SIGNALS Wednesday Tuesday Electricity North Works (From Middlewood Court To Nordens Street) Off Peak (9:30 - 15:30) 03/06/2020 16/06/2020 West () DELPH NEW ROAD,DELPH TWO-WAY SIGNALS Tuesday Monday United Utilities Works (Outside And Opposite 39) 02/06/2020 08/06/2020 Water Limited (0345 072 0829) WOOL ROAD,DOBCROSS TWO-WAY SIGNALS Friday Friday -

Foxdenton Lane Oldham Broadway Business Park Chadderton M24 1NN

Foxdenton Lane Oldham Broadway Business Park Chadderton M24 1NN On the instructions of The scheme fronts the B6189 Foxdenton Lane close to its junction with Broadgate. Junction 21 of the M60 Motorway is located approximately 1 mile away and can be accessed via Broadgate or the A663 Broadway. Oldham Broadway has excellent road communications with close proximity to Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds via the M62 Motorway. The M6 Motorway links to Birmingham to the south and Preston, Lancashire and Carlisle to the north while the M56 Motorway provides access to North Wales and South Manchester conurbations. Cobalt 2 is part of the wider Oldham Broadway Business Park where some of the occupiers include DVLA, Bifold Group, Iron Mountain, Ebay and SG Gaming. Manchester City Centre 8 miles Manchester Airport 18 miles Leeds 40 miles Birmingham 95 miles Central London 209 miles The scheme will provide two warehouse / industrial units with the following base specification: Industrial / Warehouse • Minimum 7m to eaves • Drive in and tailgate loading doors • From 37.5kn floor loading • Up to 10% office content • Environmentally designed buildings Office • Full perimeter trunking • Suspended ceilings with recessed Category II lighting • High quality decoration and carpeting • Air conditioning option Unit 1 will provide a 60,000 sq ft warehouse / industrial unit offering 2 Unit 2 will provide a 40,000 sq ft warehouse / industrial unit offering 3 no. level access doors, 4 no. dock doors and 76 car parking spaces. no. dock doors, 1 no. level access door and 55 car parking spaces. The units will be assessed for rating purposes once Each party is to be responsible for their own developed. -

Sept 2020 All Local Registered Bus Services

Service number Operator Service Details 1 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Marus Bridge - Highfield Grange Circular 1 Transdev Bolton - Darwen - Blackburn 1 Go North West Piccadilly - Chinatown - Spinningfields circular 2 Diamond Bus intu Trafford Centre - Eccles - Swinton - Bolton 2 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Pemberton - Highfield Grange circular 2 Go North West Piccadilly - Victoria - Deansgate circular 3 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Norley Hall - Kitt Green Circular 3 Go North West Piccadilly - Deansgate - Victoria circular 4 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Kitt Green - Norley Hall Circular 5 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Springfield Road - Beech Hill Circular 6 First Manchester Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 6 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Gidlow Lane - Beech Hill Circular 6 Transdev Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droyslden - Ashton 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droylsden - Ashton 8 Diamond Bus Bolton - Farnworth - Pendlebury - Manchester 8 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Hindley - Hindley Green - Wigan 9 Stagecoach Manchester Higher Folds - Leigh - Platt Bridge - Wigan 10 Arriva Brookhouse - Eccles - Pendleton - Manchester 10 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Lowton - Golborne - Ashton - Wigan 11 Stagecoach Manchester Altrincham - Wythenshawe - Cheadle - Stockport 12 Stagecoach Manchester Middleton - Boarshaw - Moorclose circular 15 Diamond Bus Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 15 Stagecoach Manchester Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 17 -

December, 1966 Landscape 5

DECEMBER, 1966 LANDSCAPE 5. C. Marshall 6 Lit. II. STOCKPORT GRAMMAR SCHOOL Patron THE PRIME WARDEN OF THE WORSHIPFUL COMPANY OF GOLDSMITHS Governors LIEUT-COL. J. A. CHRISTIE-MILLER, C.B.E., T.D., D.L., J.P., Chairman F. TOWNS, ESQ., Vice-Chairman THE REV. CANON R. SIMPSON S. D. ANDREW, ESQ., J.P. H. SMITH, ESQ., J.P. D. BLANK, ESQ., LL.B. COUNCILLOR L. SMITH, J.P. SIR GEOFFRY CHRISTIE-MILLER, J. S. SOUTHWORTH, ESQ. K.C.B., D.S.O., M.C., D.L. THE WORSHIPFUL THE MAYOR COUNCILLOR A. S. EVERETT OF STOCKPORT MRS. R. B. HEATHCOTE ALDERMAN T. J. VERNON PARRY J. C. MOULT, ESQ., J.P. PROFESSOR F. C. WILLIAMS, C.B.E., COUNTY COUNCILLOR H. E. R. PEERS, D.Sc., D.PHIL., M.I.S.F., F.R.S. O.B.E., J.P. COUNTY COUNCILLOR MRS. M. ALDERMAN R. SEATON WORTHINGTON, B.A., J.P. H. SIDEBOTHAM, ESQ., LL.M. WG-CDR. J. M. GILCHRIST, M.B.E. (Clerk to the Governors) Headmaster F. W. SCOTT, Esq., M.A. (Cantab.) Second Master W. S. JOHNSTON, Esq., M.A. (Oxon.) Assistant Masters J. H. AVERY, M.A. S. M. McDOUALL, D.S.L.C. W. D. BECKWITH F. J. NORRIS, B.A. H. BOOTH, B.Sc. H. L. READE, B.Sc. J. B. BRELSFORD, B.A. D. G. ROBERTS, B.A. M. T. BREWIS, B.A. D. J. ROBERTS, M.A. E. BROMLEY H. D. ROBINSON, B.A. D. B. CASSIE, B.Sc. A. P. SMITH, B.A. M. A. CROFTS, B.Sc. -

Greater Manchester Transport Committee

Public Document Greater Manchester Transport Committee DATE: Friday, 21 February 2020 TIME: 10.30 am VENUE: Friends Meeting House, Mount Street, Manchester Nearest Metrolink Stop: St Peters Square Wi-Fi Network: public Agenda Item Pages 1. APOLOGIES 2. CHAIRS ANNOUNCEMENTS AND URGENT BUSINESS Muhammad Karim to update Members on the recent ‘Leaders in Diversity’ accreditation and winner of “Transportation Organisation of the Year 2020” award for TfGM. 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 1 - 4 To receive declarations of interest in any item for discussion at the meeting. A blank form for declaring interests has been circulated with the agenda; Please note that this meeting will be livestreamed via www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk, please speak to a Governance Officer before the meeting should you not wish to consent to being included in this recording. please ensure that this is returned to the Governance & Scrutiny Officer at the start of the meeting. 4. MINUTES OF THE GM TRANSPORT COMMITTEE HELD 17 JANUARY 2020 5 - 16 To consider the approval of the minutes of the meeting held 17 January 2020. 5. GM TRANSPORT COMMITTEE WORK PROGRAMME 17 - 22 Report of Liz Treacy, Monitoring Officer, GMCA. 6. TRANSPORT NETWORK PERFORMANCE 23 - 34 Report of Bob Morris, Chief Operating Officer, TfGM. 7. A BETTER DEAL FOR BUS USERS Report of Alison Chew, Interim Head of Bus Services, TfGM. 7.1 A Better Deal for Bus Users 35 - 42 8. CHANGES TO THE BUS NETWORK AND REVIEW OF SUBSIDISED BUS 43 - 62 SERVICES Report of Alison Chew, Interim Head of Bus Services, TfGM. 9. METROLINK PERFORMANCE UPDATE 63 - 88 Report of Daniel Vaughan, Head of Metrolink, TfGM. -

18 October 2007 Mrs a Chadderton Headteacher Mytham Primary

Alexandra House T 08456 404040 33 Kingsway F 020 7421 6855 London [email protected] WC2B 6SE www.ofsted.gov.uk 18 October 2007 Mrs A Chadderton Headteacher Mytham Primary School Mytham Road Little Lever Bolton BL3 1JG Dear Mrs Chadderton Ofsted survey inspection programme – Science Thank you for your hospitality and co-operation, and that of your staff, during my visit on 17 October to look at work in science. As outlined in my initial letter, as well as looking at key areas of science, the visit had a particular focus on transition within and between phases, and the range of learning experiences and status of SC1. The visit provided valuable information which will contribute to our national evaluation and reporting. Published reports are likely to list the names of the contributing institutions but individual institutions will not be identified in the main text. All feedback letters will be published on the Ofsted website at the end of each half-term. The evidence used to inform the judgements made included: interviews with staff and learners, scrutiny of relevant documentation, students’ work and observation of lessons. The overall effectiveness of science was judged to be good. Achievement and standards Achievement and standards are satisfactory. At Key Stage 2 national test results were in line with the national average in 2007. They were better in 2006 when the proportion of pupils achieving the level expected was well above average. The dip in results in 2007 is associated with the 2007 cohort having lower prior attainment at Key Stage 1. Pupil’s progress is at least satisfactory and for some pupils it is good.