Swedes Publishing in Estonia up to the End of the Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Coronavirus Pandemic

Coronavirus pandemic in the EU – Fundamental Rights Implications Country: Estonia Contractor’s name: Estonian Human Rights Centre Date: 4 May 2020 DISCLAIMER: This document was commissioned under contract as background material for a comparative report being prepared by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) for the project “Coronavirus COVID-19 outbreak in the EU – fundamental rights implications”. The information and views contained in the document do not necessarily reflect the views or the official position of the FRA. The document is made available for transparency and information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or legal opinion. 1 Measures taken by government/public authorities 1.1 Emergency laws/states of emergency, including enforcement actions In Estonia, the Government of the Republic declared an emergency situation on 12 March 2020 due to the pandemic spread of the COVID-19.1 The emergency situation was initially to last until 1 May 2020, but was later extended until 17 May 2020.2 The declaration, resolution and termination of an emergency situation is regulated by the Emergency Act (Hädaolukorra seadus).3 The Emergency Act gives the person in charge of the emergency situation (the Prime Minister) the right to issue orders applying various measures. The orders include a reference that the failure to comply with the measures of the emergency situation prompt the application of the administrative coercive measures set out in the Law Enforcement Act4, and that the penalty payment is € 2000 pursuant to the Emergency Act.5 1.2 Measures affecting the general population 1.2.1 Social distancing In Estonia, after the declaration of the emergency situation, stay at home orders were imposed on people who arrived in Estonia from abroad. -

Väikesaarte Rõõmud Ja Mured 2019

Väikesaarte rõõmud ja mured Maa-ameti andmetel on Eestis üle 2000 saare. Enamik saartest on pindalalt aga niivõrd väikesed, et elatakse vaid üksikutel. Püsielanikega asustatud saared jagunevad kuue maakonna vahel. Meie riik eristab saartega suhtlemisel suursaari ja püsiasustusega väikesaari, kellele on kehtestatud teatud erisusi. Tänane ettekanne on koostatud just nende poolt kirja- pandu alusel. Koostas Linda Tikk [email protected] Abruka Saaremaa vald, Saaremaa Suurus: 8,8 km2 Rõõmud Soovid ja vajadused • SAAREVAHT olemas • Keskkonnakaitselisi probleeme pole eriti olnud,nüüd ILVES • Elekter - merekaabel Saaremaaga, • taastuvenergia - vaja päikesepaneelid • Püsiühendus Abruka-Roomassaare toimib, kuid talvise liikluskorralduse jaoks oleks vaja • Sadam kaasaegne • puudub seade kauba laadimiseks • . • • vaja kaatrile radar, öövaatlusseadmed Päästeteeistus toimib, kaater, 12 jne vabatahtlikku päästjat • Külateed tolmuvabaks • Teehooldus korras, • Internet kohe valmib • Haridus- kool ,lasteaed puudub • Pood puudub • • Kaladus 1 kutseline kalur, igas talus Perspektiivi oleks kutselistele kaluritele hobikalurid • Turismiga tegeleb 2 talu • Põllumajandus 250 veist pluss 100 Sisuliselt puudub veiste äraveo võimalus, lammast, 375 ha maad, PLK müük raskendatud hooldus • Toitlustus ja ehitus Aegna Tallinna kesklinna linnaosa, Harjumaa Suurus: 3,01 km2 Rõõmud Soovid ja vajadused Põhiline eluks vajalik saarel olemas Pääste puudulik, vajalik aastaringne päästevõimekus Heinlaid Hiiumaa vald, Hiiumaa Suurus: 1,62 km2 Soovid ja vajadused Vaja kommunikatsioone, -

Permanently Inhabited Small Islands Act

Issuer: Riigikogu Type: act In force from: 20.06.2010 In force until: 31.08.2015 Translation published: 30.04.2014 Permanently Inhabited Small Islands Act Passed 11.02.2003 RT I 2003, 23, 141 Entry into force 01.01.2004 Amended by the following acts Passed Published Entry into force 22.02.2007 RT I 2007, 25, 133 01.01.2008 20.05.2010 RT I 2010, 29, 151 20.06.2010 Chapter 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS § 1. Area of regulation of Act This Act prescribes the specifications which arise from the special nature of the insular conditions of the permanently inhabited small island and which are not provided for in other Acts. § 2. Definitions used in Act In this Act, the following definitions are used: 1) island rural municipality– rural municipality which administers a permanently inhabited small island or an archipelago as a whole; [RT I 2007, 25, 133 - entry into force 01.01.2008] 2) rural municipality which includes small islands – rural municipality which comprises permanently inhabited small islands, but is not constituting part of island rural municipalities; 3) permanently inhabited small islands (hereinafter small islands) – Abruka, Kihnu, Kessulaid, Kõinastu, Manija, Osmussaar, Piirissaar, Prangli, Ruhnu, Vilsandi and Vormsi; [RT I 2007, 25, 133 - entry into force 01.01.2008] 4) large islands – Saaremaa, Hiiumaa and Muhu. 5) permanent inhabitation – permanent and predominant residing on a small island; [RT I 2007, 25, 133 - entry into force 01.01.2008] 6) permanent inhabitant – a person who permanently and predominantly resides on a small island and data on whose residence are entered in the population register to the accuracy of a settlement unit located on a small island. -

Tõnisson, H., Orviku, K., Lapinskis, J., Gulbinskas, S., and Zaromskis, R

Text below is updated version of the chapter in book: Tõnisson, H., Orviku, K., Lapinskis, J., Gulbinskas, S., and Zaromskis, R. (2013). The Baltic States - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Panzini, E. and Williams, A. (Toim.). Coastal erosion and protection in Europe (47 - 80). UK, US and Canada: Routledge. More can be found: Kont, A.; Endjärv, E.; Jaagus, J.; Lode, E.; Orviku, K.; Ratas, U.; Rivis, R.; Suursaar, Ü.; Tõnisson, H. (2007). Impact of climate change on Estonian coastal and inland wetlands — a summary with new results. Boreal Environment Research, 12, 653 - 671. It is also available online: http://www.borenv.net/BER/pdfs/ber12/ber12-653.pdf Introduction Estonia is located in a transition zone between regions having a maritime climate in the west and continental climate in the east and is a relatively small country (45,227 km2), but its geographical location between the Fenno-scandian Shield and East European Platform and comparatively long coastline (over 4000 km) due to numerous peninsulas, bays and islands (>1,500 island), results in a variety of shore types and ecosystems. The western coast is exposed to waves generated by prevailing westerly winds, with NW waves dominant along the north-facing segment beside the Gulf of Finland, contrasting with southern relatively sheltered sectors located on the inner coasts of islands and along the Gulf of Livonia (Riga). The coastline classification is based on the concept of wave processes straightening initial irregular outlines via erosion of Capes/bay deposition, or a combination (Orviku, 1974, Orviku and Granö, 1992, Gudelis, 1967). Much coast (77%) is irregular with the geological composition of Capes and bays being either hard bedrock or unconsolidated Quaternary deposits, notably glacial drift. -

Lõputöö-Hookan-Lember.Pdf (2.127Mb)

Sisekaitseakadeemia Päästekolledž Hookan Lember RS150 PÄÄSTESÜNDMUSTE ANALÜÜS PÜSIASUSTUSEGA VÄIKESAARTEL Lõputöö Juhendaja: Häli Allas MA Kaasjuhendaja: Andres Mumma Tallinn 2018 ANNOTATSIOON Päästekolledž Kaitsmine: juuni 2018 Töö pealkiri eesti keeles: Päästesündmuste analüüs püsiasustusega väikesaartel Töö pealkiri võõrkeeles: The analysis of rescue events on small islands with permanent settlements Lühikokkuvõte: Töö on kirjutatud eesti keeles ning eesti ja inglise keelse kokkuvõttega. Töö koos lisadega on kirjutatud kokku 61 lehel, millest põhiosa on 38 lehekülge. Lõputöö koosneb kolmest peatükist, kus on kasutatud kahte tabelit ja seitseteist joonist. Valitud teema uurimisprobleemiks on tervikliku ülevaate puudumine väikesaarte sündmustest, mis kuuluvad Päästeameti valdkonda. Väikesaartele toimub reageerimine erinevalt ning sõltuvalt aastaajast on reageerimine raskendatud. Ühtseid põhimõtteid rahvaarvu või sündmuste arvu kohta ei ole. Lõputöö eesmärk on analüüsida päästesündmusi väikesaartel aastatel 2009-2017 ning järeldada, millist päästevõimekust vajavad püsiasutustega väikesaared. Lõputöös antakse saartest ülevaade, mis on valimis välja toodud ning visualiseeritakse joonise abil saartel elavate püsielanike arv. Eesmärgi saavutamiseks kasutati kvantitatiivset uurimismeetodit, kus Häirekeskuselt saadud andmed korrastati ja analüüsiti. Lõputöös anti ülevaade, millised on sündmused saartel ning tehti järeldused, kuidas tagada kiire ja kvaliteetse abi kättesaadavus. Saartel, kus elanike arv on väike ning sündmuste arv minimaalne, -

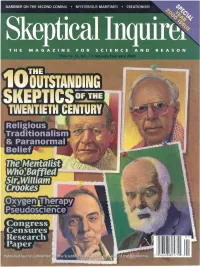

Here Are Many Heroes of the Skeptical Movement, Past and Present

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONA! (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Univ. Dorothy Nelkin, sociologist, New York Univ. Toronto Henry Gordon, magician, columnist, Joe Nickell,* senior research fellow, CSICOP Steve Allen, comedian, author, composer, Toronto Lee Nisbet* philosopher, Medaille College pianist Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Bill Nye, science educator and television Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. host, Nye Labs Albany, Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts James E. Oberg, science writer Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Kentucky University of Miami Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist Univ. of Wales Health Sciences Univ. consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein, * biopsychologist, Simon Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human W. V. Quine, philosopher, Harvard Univ. Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada understanding and cognitive science, Milton Rosenberg, psychologist. Univ. of Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Indiana Univ. Chicago Southern California Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Univ. of the Physics and professor of history of science, of medicine, Stanford Univ. West of England, Bristol Harvard Univ. -

Tree-Ring Dating in Estonia

University of Helsinki Faculty of Science Department of Geology View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto TREE-RING DATING IN ESTONIA ALAR LÄÄNELAID HELSINKI 2002 Doctoral dissertation to be defended in University of Helsinki, Faculty of Science To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Science of the University of Helsinki, for public criticism in Auditorium E204, Physicum, Kumpula, Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2, University of Helsinki, on November 29th, at 2 o'clock in the afternoon. Custos: Prof. Matti Eronen, Department of Geology, Faculty of Science of University of Helsinki, Finland Opponent: Prof. Dieter Eckstein, Institute for Wood Biology of University of Hamburg, Germany Reviewers: Dr. Tomasz Wazny, Dendrochronological Laboratory, Faculty of Conservation and Restoration of Academy of Fine Arts, Warsaw, Poland Prof. Olavi Heikkinen, Department of Geography of University of Oulu, Finland © Alar Läänelaid, 2002 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tiigi 78, Tartu 50410 ISBN 9985–78–740–4 Tellimus nr. 488 2 CONTENTS LIST OF ORIGINAL PUBLICATIONS ...................................................... 4 PREFACE ..................................................................................................... 5 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 6 1.1. What is tree-ring dating? .................................................................. 6 1.2. Briefly about the -

Brief an Den Gouverneur Des Bundesstaates

HVD · Wallstr. 65 · 10179 Berlin Governor Abdullahi Umar Ganduje Office of the Governor Government House Kano Kano State, Nigeria Telephone: (+234) 7044-930000 Email: [email protected] 28.4.2021 Betreff: Fortwährende Inhaftierung von Mubarak Bala Sehr geehrter Herr Gouverneur, Die unterzeichnenden 51 Organisationen und Einzelpersonen schreiben Ihnen heute, um unsere tiefe Besorgnis über die andauernde Inhaftierung von Mubarak Bala, dem Präsidenten der Humanist Association of Nigeria, auszudrücken, der nun schon seit 365 Tagen willkürlich inhaftiert ist. Wir fordern Sie auf, Herrn Bala sofort und bedingungslos freizulassen. Mubarak Bala, geboren 1984 im Bundesstaat Kano, Nordnigeria, ist ein prominentes und angesehenes Mitglied der Humanistischen Bewegung. Der gelernte Chemieingenieur ist Präsident der Humanist Association of Nigeria. Er hat im Internet und den sozialen Medien Kampagnen zur Förderung der Menschenrechte, Religions- und Weltanschauungsfreiheit und zur Sensibilisierung für religiösen Extremismus gestartet. Seit er 2014 dem Islam abgeschworen hat, ist Herr Bala Opfer von Morddrohungen und Schikanen geworden. Im Juni desselben Jahres wurde er gegen seinen Willen in einer psychiatrischen Einrichtung im Bundesstaat Kano festgehalten. Die globale Organisation Humanists International und ihre Mitgliedsorganisationen sind tief besorgt um sein Wohlergehen. Die Verhaftung von Herrn Bala am 28. April 2020 folgte auf eine Petition, die am 27. April beim Polizeipräsidenten des Kano-Kommandos von einer lokalen Anwaltskanzlei eingereicht wurde. Es wurde behauptet, Mubarak Bala hätte in seinen Facebook-Posts den Propheten Mohammed beleidig, was gegen Abschnitt 26(1)(c) des ‚Cybercrimes Acts‘ verstößt. Humanistischer Wallstr. 65 · 10179 Berlin Amtsgericht IBAN Geschäftskonto: Verband Tel.: 030 61390-434 · Fax: - Charlottenburg DE68 1002 0500 0003 Deutschlands e.V. 450 VR-Nr. -

Wave Climate and Coastal Processes in the Osmussaar–Neugrund Region, Baltic Sea

Coastal Processes II 99 Wave climate and coastal processes in the Osmussaar–Neugrund region, Baltic Sea Ü. Suursaar1, R. Szava-Kovats2 & H. Tõnisson3 1Estonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Estonia 2Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, Estonia 3Institute of Ecology, Tallinn University, Estonia Abstract The aim of the paper is to investigate hydrodynamic conditions in the Neugrund Bank area from ADCP measurements in 2009–2010, to present a local long-term wave hindcast and to study coastal formations around the Neugrund. Coastal geomorphic surveys have been carried out since 2004 and analysis has been performed of aerial photographs and old charts dating back to 1900. Both the in situ measurements of waves and currents, as well as the semi-empirical wave hindcast are focused on the area known as the Neugrund submarine impact structure, a 535 million-years-old meteorite crater. This crater is located in the Gulf of Finland, about 10 km from the shore of Estonia. The depth above the central plateau of the structure is 1–15 m, whereas the adjacent sea depth is 20– 40 m shoreward and about 60 m to the north. Limestone scarp and accumulative pebble-shingle shores dominate Osmussaar Island and Pakri Peninsula and are separated by the sandy beaches of Nõva and Keibu Bays. The Osmussaar scarp is slowly retreating on the north-western and northern side of the island, whereas the coastline is migrating seaward in the south as owing to formation of accumulative spits. The most rapid changes have occurred either during exceptionally strong single storms or in periods of increased cyclonic and wave activity, the last high phase of which occurred in 1980s–1990s. -

Woodworking in Estonia

WOODWORKING IN ESTONIA HISTORICAL SURVEY By Ants Viires Translated from Estonian by Mart Aru Published by Lost Art Press LLC in 2016 26 Greenbriar Ave., Fort Mitchell, KY 41017, USA Web: http://lostartpress.com Title: Woodworking in Estonia: Historical Survey Author: Ants Viires (1918-2015) Translator: Mart Aru Publisher: Christopher Schwarz Editor: Peter Follansbee Copy Editor: Megan Fitzpatrick Designer: Meghan Bates Index: Suzanne Ellison Distribution: John Hoffman Text and images are copyright © 2016 by Ants Viires (and his estate) ISBN: 978-0-9906230-9-0 First printing of this translated edition. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. This book was printed and bound in the United States. CONTENTS Introduction to the English Language Edition vii The Twisting Translation Tale ix Foreword to the Second Edition 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Literature, Materials & Methods 2 2. The Role Played by Woodwork in the Peasants’ Life 5 WOODWORK TECHNOLOGY 1. Timber 10 2. The Principal Tools 19 3. Processing Logs. Hollowing Work and Sealed Containers 81 4. Board Containers 96 5. Objects Made by Bending 127 6. Other Bending Work. Building Vehicles 148 7. The Production of Shingles and Other Small Objects 175 8. Turnery 186 9. Furniture Making and Other Carpentry Work 201 DIVISION OF LABOR IN THE VILLAGE 1. The Village Craftsman 215 2. Home Industry 234 FINAL CONCLUSIONS 283 Index 287 INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION feel like Captain Pike. -

Looduslik Ja Antropogeenne Morfodünaamika Eesti Rannikumere

THESIS ON CIVIL ENGINEERING F22 Lithohydrodynamic processes in the Tallinn Bay area ANDRES KASK TUT PRESS TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Faculty of Civil Engineering Department of Mechanics The dissertation was accepted for the defence of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy on June 28, 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Tarmo Soomere Department of Mechanics and Institute of Cybernetics Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia Opponents: Prof. Dr. Jan Harff Foundation for Polish Science Fellow, Institute of Marine Sciences University of Szczecin, Poland Prof. Dr. Anto Raukas Leading research scientist, Institute of Geology Tallinn University of Technology, Member of Estonian Academy of Sciences Defence of the thesis: August 21, 2009, Institute of Cybernetics at Tallinn University of Technology, Akadeemia tee 21, 12618 Tallinn, Estonia Declaration: Hereby I declare that this doctoral thesis, my original investigation and achievement, submitted for the doctoral degree at Tallinn University of Technology has not been submitted for any academic degree. Andres Kask Copyright: Andres Kask, 2009 ISSN 1406-4766 ISBN 978-9985-59-923-5 3 EHITUS F22 Litohüdrodünaamilised protsessid Tallinna lahe piirkonnas ANDRES KASK TUT PRESS 4 Contents List of tables .............................................................................................................. 7 List of figures ............................................................................................................ 7 Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

2017 Lighthouse Tours a Better Way to See Lighthouses! What Can You Expect from a USLHS Tour?

UNITED STATES LIGHTHOUSE SOCIETY 2017 LIGHTHOUSE TOURS A BETTER WAY TO SEE LIGHTHOUSES! WHAT CAN YOU EXPECT FROM A USLHS TOUR? You will be in the company of lighthouse lovers, history buffs, world travelers, and life-long learners A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR who enjoy the camaraderie of old friends and new. Our members are known for being fun-loving and People all over the world are naturally drawn to inclusive! Single travelers are always welcome. lighthouses. Typically located in the most beautiful locations on the planet, they reward those We are often able to explore, climb, and/or of us who love to travel with stunning natural photograph lighthouses, not open to the public, landscapes and transcendent vistas. Historically, usually found in remote locations. Your journey lighthouses were built to save lives, giving them to a lighthouse could involve charter boats, off a human connection unlike any other historic road vehicles, helicopters, float planes, or perhaps horse drawn carriages! Travelers have even found landmark. They represent attributes all of us themselves on golf carts, jet boats, and lobster strive for: compassion, courage, dedication, selflessnessand humility...and trawlers just to get that perfect lighthouse when you visit a lighthouse, you are destined to be moved in ways that viewpoint! connect you with something larger than yourself. U.S. Lighthouse Society tours are designed intentionally for those who Tour itineraries are designed to provide love traveling to amazing places and who desire to connect with others opportunities to visit other regional landmarks and who share a common passion for lighthouses and what they stand for.