Voting Rights Act of 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Student Interracial Ministry, Liberal Protestantism, and the Civil Rights Movement, 1960-1970

Revolution and Reconciliation: The Student Interracial Ministry, Liberal Protestantism, and the Civil Rights Movement, 1960-1970 David P. Cline A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of doctor of philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Advisor: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Reader: W. Fitzhugh Brundage Reader: William H. Chafe Reader: Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp Reader: Heather A. Williams © 2010 David P. Cline ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT DAVID P. CLINE: Revolution and Reconciliation: The Student Interracial Ministry, Liberal Protestantism, and the Civil Rights Movement, 1960-1970 (Under the direction of Jacquelyn Dowd Hall) The Student Interracial Ministry (SIM) was a seminary-based, nationally influential Protestant civil rights organization based in the Social Gospel and Student Christian Movement traditions. This dissertation uses SIM’s history to explore the role of liberal Protestants in the popular revolutions of the 1960s. Entirely student-led and always ecumenical in scope, SIM began in 1960 with the tactic of placing black assistant pastors in white churches and whites in black churches with the goal of achieving racial reconciliation. In its later years, before it disbanded in mid-1968, SIM moved away from church structures, engaging directly in political and economic movements, inner-city ministry and development projects, and college and seminary teaching. In each of these areas, SIM participants attempted to live out German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer's exhortation to “bring the church into the world.” Revolution and Reconciliation demonstrates that the civil rights movement, in both its “classic” phase from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s and its longer phase stretching over most of the twentieth century, was imbued with religious faith and its expression. -

Civil Rights Movement and the Legacy of Martin Luther

RETURN TO PUBLICATIONS HOMEPAGE The Dream Is Alive, by Gary Puckrein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Excerpts from Statements and Speeches Two Centuries of Black Leadership: Biographical Sketches March toward Equality: Significant Moments in the Civil Rights Movement Return to African-American History page. Martin Luther King, Jr. This site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. THE DREAM IS ALIVE by Gary Puckrein ● The Dilemma of Slavery ● Emancipation and Segregation ● Origins of a Movement ● Equal Education ● Montgomery, Alabama ● Martin Luther King, Jr. ● The Politics of Nonviolent Protest ● From Birmingham to the March on Washington ● Legislating Civil Rights ● Carrying on the Dream The Dilemma of Slavery In 1776, the Founding Fathers of the United States laid out a compelling vision of a free and democratic society in which individual could claim inherent rights over another. When these men drafted the Declaration of Independence, they included a passage charging King George III with forcing the slave trade on the colonies. The original draft, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, condemned King George for violating the "most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people who never offended him." After bitter debate, this clause was taken out of the Declaration at the insistence of Southern states, where slavery was an institution, and some Northern states whose merchant ships carried slaves from Africa to the colonies of the New World. Thus, even before the United States became a nation, the conflict between the dreams of liberty and the realities of 18th-century values was joined. -

Viewer's Guide

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

Educator's Guide

Holiday House Educator’s Guide Because They Marched The People’s Campaign for Voting Rights That Changed America Russell Freedman Grades 5 up HC: 978-0-8234-2921-9 • e-book: 978-0-8234-3263-9 • $20.00 Illustrated with photographs. Includes a time line, source notes, a bibliography, and an index. ALA Notable Children’s Book A Kirkus Reviews Best Children’s Book A Booklist Editors’ Choice ★ “A beautifully written narrative that is moving as well as informative.” —Booklist, starred review ★ “Richly illustrated.” —Kirkus Reviews, starred review ★ “Clear, concise storytelling.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review About the Book For the 50th anniversary of the march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, Newbery Medalist Russell Freedman has written a riveting account of this pivotal event in the history of civil rights. In the early 1960s, tensions in the segregated South intensified. Tired of reprisals for attempting to register to vote, Selma’s black community began to protest. The struggle received nationwide attention in January 1965, when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led a voting rights march and was attacked by a segregationist. In February, the shooting of an unarmed demonstrator by an Alabama state trooper inspired a march from Selma to the state capital, an event that got off to a horrific start on March 7 as law officers attacked peaceful demonstrators. Broadcast throughout the world, the violence attracted widespread outrage and spurred demonstrators to complete the march at any cost. Illustrated with more than forty photographs, this is an essential chronicle of events every American should know. www.HolidayHouse.com Pre-Reading Activity The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified on February 3, 1870. -

I've Seen the Promised Land: a Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson Mauricio E

SURGE Center for Public Service 1-20-2014 I've Seen the Promised Land: A Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson Mauricio E. Novoa Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge Part of the African American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Oral History Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Novoa, Mauricio E., "I've Seen the Promised Land: A Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson" (2014). SURGE. 43. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge/43 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge/43 This open access blog post is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I've Seen the Promised Land: A Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson Abstract You asked if I had any thoughts or comments at the end of our visit, and I stood and said nothing. I opened my mouth, but instead of giving you words my throat was sealed by a dam of speechlessness while my eyes wept out all the emotions and heartache that I wanted to share with you. The others in my group were able to express their admiration, so I wanted to do the same. -

Jimmie Lee Jackson and the Events in Selma

Jimmie Lee Jackson and the Events in Selma On the night of February 18, 1965 a group of African-Americans gathered at a church in Marion, Alabama. Among those individuals at Zion's Chapel Methodist Church was Jimmie Lee Jackson, a Vietnam-War veteran. Fighting for his country, however, was not enough in the segregated South for 29-year-old Jimmie Lee to vote. He had tried to register, for several years, but there was always some reason during the Jim-Crow era to keep him from becoming a registered voter. Inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., people in Marion—a town close to Selma—met to talk about how to change things. Why should American citizens be denied the right to vote when the U.S. Constitution allowed it? There was a special purpose for the gathering on February 18th. A young civil-rights activist named James Orange, a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was incarcerated at the Perry County jail. Cordy Tindell ("C. T.") Vivian, a close friend of Dr. King, was planning to lead a group of around 500 peaceful protesters on a walk to the nearby jail. When the marchers reached the post office, they were met by Marion City police officers, sheriff's deputies and Alabama State Troopers who’d formed a line preventing the protestors from moving forward. Somehow the street lights were turned off (to this day it’s not clear how that happened). Under cover of darkness, the police started to beat the marching protestors. Among the injured were Richard Valeriani, a White-House journalist for NBC News, and two cameramen who worked for United Press International. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

Murder of Innocents – the IRA Attack That Repulsed the World

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article Murder of innocents – the IRA attack that HOME repulsed the world This article appears thanks to the Irish History (Diana Rusk, Irish News) News. Subscribe to the Irish News NewsoftheIrish The IRA bombing at a Remembrance Day commemoration in the Co Fermanagh town of Enniskillen 20 years ago this week killed 11 people, injured 63 and repulsed the world. Book Reviews & Book Forum Amateur video footage of the aftermath of the explosion on November 8 1987 was broadcast internationally, vividly Search / Archive portraying the suffering of innocent victims. Back to 10/96 Half were Presbyterians who had inadvertently stood the closest Papers to the hidden 40lb device so that they could be convenient to their place of worship. Reference There were three married couples – Wesley Armstrong (62) and wife Bertha (55), Billy Mullan (74) and wife Agnes (73), Kit About Johnston (71) and wife Jessie (62). The others who died were Sammy Gault (49), Ted Armstrong Contact (52), Johnny Megaw (67), Alberta Quinton (72) and the youngest victim, Marie Wilson (20). A 12th person, Ronnie Hill, who slipped into a coma days after the explosion, never woke up and died almost 14 years later. For the first time in the Troubles, the IRA admitted it had made a mistake, planting the device in a building owned by the Catholic church to, they said, target security forces patrolling the parade. The bombing is believed to be one of the watershed incidents of the Troubles largely because of the international outcry against the violence. -

The Daily Egyptian, March 31, 1965

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC March 1965 Daily Egyptian 1965 3-31-1965 The aiD ly Egyptian, March 31, 1965 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_March1965 Volume 46, Issue 113 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, March 31, 1965." (Mar 1965). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1965 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in March 1965 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~§OCjA[ STUDIES Prof to Talk on 'I"{sanity Called Love' "The Insanity Called Love" phelia, ~er:S.p~it .. ~~~... "Se, ·.~:~.: ·.··-·~i"1"'.·.~:. will be the theme of the 1965 anctsQLo.v~". and "Why be 1.."~';' ..... ... .~. Throgmorton lecture series to MOfill~" ~ _.. '~ , 'w t b... presented by the Baptist OItif:.'MOFdi' 3.:mrUlle: ~isyd- '''. Fe Foundation at 7:30 p.m. during ney, Australia, ho 1 d s a April 12-15 at the Baptist doctor's degr ... e from South Foundation Chapd. western Seminary. He is John W. Drakeford, j:.ro- author of a booklet title "The fessor of psychology and coun- Ego and I." co-author of .. An seling and director of the Introduction to PastoralCoun- . Baptist Marriage and Family seling," and is a regular • SOUTHERH ''''''HOIS UHIVERSITY Counseling Center of Fort speaker on the Southern Worth, Tex., will be guest Baptist Radio Program, Carbondole, Illinois lecturer for the series. "Master Contro!." He will speak on • 'The Roots The Throgmorton Lectures Volume 46 Wednosdoy, March 31, 1965 Number 113 of Romantic Love," "Schiza- fund was established in 1962. -

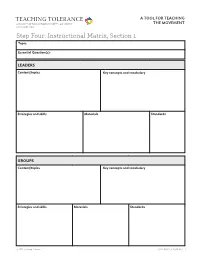

Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic: Essential Question(s): LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards GROUPS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: EVENTS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards HISTORICAL CONTEXT Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: OPPOSITION Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards TACTICS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: CONNECTIONS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 (SAMPLE) Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Martin Luther King Jr., A. -

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Topic: Civil Rights History Grade level: Grades 4 – 6 Subject Area: Social Studies, ELA Time Required: 2 -3 class periods Goals/Rationale Bring history to life through reenacting a significant historical event. Raise awareness that the civil rights movement required the dedication of many leaders and organizations. Shed light on the power of words, both spoken and written, to inspire others and make progress toward social change. Essential Question How do leaders use written and spoken words to make change in their communities and government? Objectives Read, analyze and recite an excerpt from a speech delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Identify leaders of the Civil Rights Movement; use primary source material to gather information. Reenact the March on Washington to gain a deeper understanding of this historic demonstration. Connections to Curriculum Standards Common Core State Standards CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.1 Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.2 Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 5 topic or subject area. CCSS.ELA-Literacy SL.5.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, using formal English when appropriate to task and situation. National History Standards for Historical Thinking Standard 2: The student comprehends a variety of historical sources. -

Volume I Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons Dated 15 June 2010 for The

Report of the Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 15 June 2010 for the Report of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry The Rt Hon The Lord Saville of Newdigate (Chairman) Bloody Sunday Inquiry – Volume I Bloody Sunday Inquiry – Volume The Hon William Hoyt OC The Hon John Toohey AC Volume I Outline Table of Contents General Introduction Glossary Principal Conclusions and Overall Assessment Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online The Background to Bloody www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail Sunday TSO PO Box 29, Norwich NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Order through the Parliamentary Hotline Lo-Call: 0845 7 023474 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone: 0870 240 3701 The Parliamentary Bookshop 12 Bridge Street, Parliament Square, London SW1A 2JX This volume is accompanied by a DVD containing the full Telephone orders/General enquiries: 020 7219 3890 Fax orders: 020 7219 3866 text of the report Email: [email protected] Internet: www.bookshop.parliament.uk TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from £572.00 TSO Ireland 10 volumes 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD not sold Telephone: 028 9023 8451 Fax: 028 9023 5401 HC29-I separately Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 15 June 2010 for the Report of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry The Rt Hon The Lord Saville of Newdigate (Chairman) The Hon William Hoyt OC The Hon John Toohey AC Ordered by the House of Commons