People of the State of Illinois Vs. John Gacy: the Functioning of the Insanity Defense at the Limits of the Criminal Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incurable Psychopaths?

Incurable Psychopaths? Marianne Kristiansson, MD Treatment, comprising pharmacotherapy and an educational program based on cognitive behavior therapy, of four psychopathic, criminal men fulfilling the crite- ria for borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder is de- scribed. The diagnoses were made during a forensic psychiatric evaluation. An estimation of the capacity of the central serotonergic system was performed by analysing the platelet monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity. The pharmacotherapy was combined with an educational program involving strategies for developing better impulse control. All four men had earlier been regarded as resistant to conventional therapy. In the present cases, a combined psychosocial and biolog- ical approach seemed to be effective in developing an increased control of im- pulses, leading to improved coping strategies. Controlled studies are needed in order to clarify whether the described treatment program proves beneficial. Psychopathy, as originally described by personality disorder according to DSM- Cleckley,' comprises a set of clinical 111-R.~ characteristics including superficial The possibility of curing or even trying charm, unreliability, untruthfulness, lack to treat criminal psychopathic individuals of remorse or shame, failure to learn by is often looked upon as futile. Most treat- experience, incapacity for love, general ment programs involve various psycho- poverty in major affective relations, and social interventions and little effort has failure to follow any life -

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Summer 2017 A quarterly report by the Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins, Esq. Consultant to the Criminal Justice Project NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Summer 2017 (As of July 1, 2017) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2,817 Race of Defendant: White 1,196 (42.46%) Black 1,168 (41.46%) Latino/Latina 373 (13.24%) Native American 26 (0.92%) Asian 53 (1.88%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,764 (98.12%) Female 53 (1.88%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 33 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 20 Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico [see note below], New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Mexico repealed the death penalty prospectively. The men already sentenced remain under sentence of death.] Death Row U.S.A. Page 1 In the United States Supreme Court Update to Spring 2017 Issue of Significant Criminal, Habeas, & Other Pending Cases for Cases to Be Decided in October Term 2016 or 2017 1. CASES RAISING CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS First Amendment Packingham v. North Carolina, No. 15-1194 (Use of websites by sex offender) (decision below 777 S.E.2d 738 (N.C. -

Mob Storms Into Tehran As Oil Halts

PAGE TWENTY-EIGHT - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester, Conn.. Wed.. Dec. 27. I97B other information could you Now. I’m not sure what colic sometimes benefit cage near the gallbladder give me about treatment of kind of X ray you had for from a low-fat diet. Fat region may be confused with the colic? your gallbladder, but some stimulates the gallbladder to discomfort from gallbladder What’s up In auto theft? DEAR READER - It is stones show up on an X ray contract, resulting in colic. disease. unlikely that your pain is and other don’t, depending This is not true of either pure' When such patients have Think twice about parking your car on a Boston street. HEALTH caused by gallbladder colic. upon their chemical compo protein or carbohydrates. their gallbladder removed, According to a recent survey by a'leading Insurance V^y? Because you don’t sition. I am sending you The often they don’t get relief company, Beantown has the highest auto thelt rate In the 1 " Lawrence E.Lamb.M.D. have any gallstones. Most The ones that don’t have to Health Letter number 4-9, from their symptoms be nation. attacks of gallbladder colic be visualized by X ray after Gall Stones and Gall cause the pain wasn't Here are the auto theft rates per 100.000 people as well Senator*s Win Costly 1 East Catholic Boysj Girls 1 Body Count Now 17 1 Guyana Top Headliner are caused by sudden ob taking a gallbladder dye. Bladder Disease. It will give caused by the gallbladder to as the costs ol a comprehensive theft policy on a struction of the bile duct — T his^ usi^ally done by giv you more information on begin with. -

Tongass National Forest

S. Hrg. 101-30, Pt. 3 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS, NATIONAL PARKS AND FORESTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIRST CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 987 *&< TO AMEND THE ALASKA NATIONAL INTEREST LANDS CONSERVATION ACT, TO DESIGNATE CERTAIN LANDS IN THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST AS WILDERNESS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES FEBRUARY 26, 1990 ,*ly, Kposrretr PART 3 mm uwrSwWP Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Boston P«*5!!c y^rary Boston, MA 116 S. Hrg. 101-30, Pr. 3 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS, NATIONAL PAEKS AND FORESTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIRST CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 987 TO AMEND THE ALASKA NATIONAL INTEREST LANDS CONSERVATION ACT, TO DESIGNATE CERTAIN LANDS IN THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST AS WILDERNESS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES FEBRUARY 26, 1990 PART 3 Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 29-591 WASHINGTON : 1990 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES J. BENNETT JOHNSTON, Louisiana, Chairman DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas JAMES A. McCLURE, Idaho WENDELL H. FORD, Kentucky MARK O. HATFIELD, Oregon HOWARD M. METZENBAUM, Ohio PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BILL BRADLEY, New Jersey MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico FRANK H. MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIMOTHY E. WIRTH, Colorado DON NICKLES, Oklahoma KENT CONRAD, North Dakota CONRAD BURNS, Montana HOWELL T. -

The Psychological Perspective in Legal Education

Volume 84 Issue 1 Article 7 October 1981 All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers: The Psychological Perspective in Legal Education James R. Elkins West Virginia University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation James R. Elkins, All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers: The Psychological Perspective in Legal Education, 84 W. Va. L. Rev. (1981). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol84/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elkins: All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers: The Psychological Perspect "ALL MY FRIENDS ARE BECOMING STRANGERS": THE PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE IN LEGAL EDUCATIONt JAMES R. ELKINS* PREFACE That I adopted as part of the title for this article "All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers"' suggests the need for expla- nation-what humanistic sociologists call a reflexive statement. More simply put, this article needs a preface. The psychiatrist, Robert Coles, has suggested that a preface permits an author to tell where he stands, and unquestionably in so doing he runs the risk of self-centeredness if not self-display .... We owe it to ourselves and our readers to show something of our lives and our purposes, to indicate, as it were, the context out of which a particular book has emerged.2 This article began as an angry and polemical response to an article by William Simon calling into question what he called The Psychological Vision in legal education.' Upon first reading the Simon article I was dismayed that anyone could be so bold and presumptuous as to attack the psychological perspective and its role in legal education. -

The John Wayne Gacy Murders Pdf Free Download

KILLER CLOWN: THE JOHN WAYNE GACY MURDERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Terry Sullivan,Professor Peter T Maiken | 419 pages | 01 May 2013 | Kensington Publishing | 9780786032549 | English | New York, United States Killer Clown: The John Wayne Gacy Murders by Terry Sullivan Armed with the signed search warrant, police and evidence technicians drove to Gacy's home. On their arrival, officers found Gacy had unplugged his sump pump , flooding the crawl space with water; to clear it, they simply replaced the plug and waited for the water to drain. After it had done so, evidence technician Daniel Genty entered the byfoot 8. Genty immediately shouted to the investigators that they could charge Gacy with murder, adding, "I think this place is full of kids". A police photographer then dug in the northeast corner of the crawl space, uncovering a patella. The two then began digging in the southeast corner, uncovering two lower leg bones. The victims were too decomposed to be Piest. As the body discovered in the northeast corner was later unearthed, a crime scene technician discovered the skull of a second victim alongside this body. Later excavations of the feet of this second victim revealed a further skull beneath the body. After being informed that the police had found human remains in his crawl space and that he would now face murder charges, Gacy told officers he wanted to "clear the air", adding he had known his arrest was inevitable since the previous evening, which he had spent on the couch in his lawyers' office. In the early morning hours of December 22, and in the presence of his lawyers, Gacy provided a formal statement in which he confessed to murdering approximately 30 young males—all of whom he claimed had entered his house willingly. -

Perceived Social Rank, Social Expectation, Shame and General Emotionality Within Psychopathy

Perceived social rank, social expectation, shame and general emotionality within psychopathy Sarah Keen D. Clin.Psy. Thesis (Volume 1), 2008 University College London UMI Number: U591545 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591545 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Overview Within the psychological literature, the self-conscious emotion of shame is proving to be an area of growing interest. This thesis addresses the application of this emotion, as well as self and social evaluative processes, to our understanding of offenders, specifically those high in psychopathic traits. Part 1 reviews the literature concerning emotionality within psychopathy, in order to assess the capabilities, as well as the deficits that people with psychopathic traits demonstrate. Emotions classified as ‘moral’ or ‘self-conscious’, namely empathy, sympathy, guilt, remorse, shame, embarrassment and pride, are investigated. From the review it is clear that psychopaths are not the truly unemotional individuals that they are commonly portrayed as being, but instead experience many emotions to varying degrees. This paper concludes by highlighting possible areas for further exploration and research. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

I PSYCHOPATHY and the INSANITY DEFENSE

i PSYCHOPATHY AND THE INSANITY DEFENSE: A GROUNDED THEORY EXPLORATION OF PUBLIC PERCEPTION BY ELISABETH KNOPP A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Forensic Psychology California Baptist University School of Behavioral Sciences 2017 ii © 2017 Knopp, Elisabeth All Rights Reserved iii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Mitchell, the love of my life. Thank you for all the love and support throughout this writing process, all the pep talks, and helping me fight procrastination! You are my best friend, my favorite study buddy, and my best accountability partner! Without your positive attitude and encouragement, I may not have gotten through my numerous late night writing sessions. I would also like to dedicate this to my parents who have been there for me all the life and have always pushed me to do my best. I can’t imagine my life without your support and encouragement. You gave me so many opportunities to succeed and wouldn’t ever let me settle for less than my best. You have helped shape me into the person I am today. I wouldn’t be here without you! iv Acknowledgements I would like to thank my wonderful thesis chair, Dr. Anne-Marie Larsen, for her immense help while writing this thesis. Without your guidance, our brainstorming sessions, and all your assistance, I likely wouldn’t even have a completed thesis. Thank you for pushing me to take opportunities to present at conferences and colloquiums and better my resume through research. You have been an immense support to me during these two years and I have always valued your advice and encouragement. -

Fibernet Channel Lineup

FIBERNET CHANNEL LINEUP VALUE TIER 2069 HGTV 3026 NickToons LATINO TIER 1001 PBS WETP – Knoxville 2070 Food Network 3027 Boomerang 5000 Sorpresa! 1002 PBS Kids 2071 National Geography 3040 Science Channel 5001 ESPN Deportes 1003 PBS Create 2072 History Channel 3041 Destination America 5002 Cine Mexicano 1004 FiberNET 4 2073 Discovery Channel 3042 Nat Geo Wild 5003 CNN En Espanol 1005 WAGV – Harlan, KY 2074 TLC 3043 diy Network 5004 FOX Deportes 1006 ABC WATE – Knoxville 2075 Animal Planet 3044 Smithsonian 5005 Discovery En Espanol 1007 Morristown TV Today 2076 Investigation Discovery 3045 RFD TV 5006 Discovery Familia 1008 CBS WVLT – Knoxville 2077 Travel Channel 3046 FYI 5007 Enlace 1009 WVLT2 - My East TN TV 2078 E! 3047 Vice 5008 Telemundo 1010 NBC WBIR – Knoxville 2079 Paramount Network 3050 Crimes & Investigations 5009 Universo 1011 FOX WTNZ – Knoxville 2080 Comedy Central 3052 Comedy.TV 1012 CW WBXX – Knoxville 2081 GSN (Game Show Network) 3053 Recipe.TV PREMIUM CHANNELS 1013 ION WPXK – Knoxville 2082 OWN 3054 Cars.TV 6000 HBO 1014 WKNX - Knoxville 2083 TV Land 3055 Pets.TV 6001 HBO 2 1015 WVLR – Tazewell 2084 News Nation 3056 My Destination.TV 6002 HBO Signature 1016 MeTV 2085 WeTV 3057 ES.TV 6003 HBO Family 1017 INSP 2086 truTV 3058 Military History 6004 HBO Latino 1018 Weather Channel 2087 Lifetime 3060 Fido TV 6005 HBO Comedy 1020 ReTV 2088 Freeform 3061 American Heroes Channel 6006 HBO Zone 1028 HSN 2089 Hallmark 3062 Cooking Channel 6007 HBO (West) 1029 HSN 2 2090 Hallmark Movies 3063 Discovery Life 6008 HBO 2 (West) 1030 -

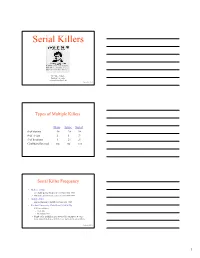

Serial Killers

Serial Killers Dr. Mike Aamodt Radford University [email protected] Updated 01/24/2010 Types of Multiple Killers Mass Spree Serial # of victims 4+ 2+ 3+ # of events 1 1 3+ # of locations 1 2+ 3+ Cooling-off period no no yes Serial Killer Frequency • Hickey (2002) – 337 males and 62 females in U.S. from 1800-1995 – 158 males and 29 females in U.S. from 1975-1995 • Gorby (2000) – 300 international serial killers from 1800-1995 • Radford University Data Base (1/24/2010) – 1,961 serial killers • US: 1,140 • International: 821 – Number of serial killers goes down with each update because many names listed as serial killers are not actually serial killers Updated 01/24/2010 1 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics - Worldwide • Male – Our data base: 88.27% – Kraemer, Lord & Heilbrun (2004) study of 157 serial killers: 96% • White – 66.5% of all serial killers (68% in Kraemer et al, 2004) – 64.3% of male serial killers – 83% of female serial killers • Average intelligence – Mean of 101 in our data base (median = 100) –n = 107 • Seldom involved with groups Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Age at First Kill Race N Mean Our data (2010) 1,518 29.0 Kraemer et al. (2004) 157 31 Hickey (2002) 28.5 Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics – Average age is 29.0 • Males – 28.8 is average age at first kill • 9 is the youngest (Robert Dale Segee) • 72 is the oldest (Ray Copeland) – Jesse Pomeroy (Boston in the 1870s) • Killed 2 people and tortured 8 by the age of 14 • Spent 58 years in solitary confinement until he died • Females – 30.3 is average age at first kill • 11 is youngest (Mary Flora Bell) • 66 is oldest (Faye Copeland) Updated 01/24/2010 2 General Serial Killer Profile Race Race U.S. -

How Does Psychopathy Relate to Humor and Laughter? Dispositions Toward Ridicule and Being Laughed At, the Sense of Humor, and Psychopathic Personality Traits

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 How does psychopathy relate to humor and laughter? Dispositions toward ridicule and being laughed at, the sense of humor, and psychopathic personality traits Proyer, Rene T ; Flisch, Rahel ; Tschupp, Stefanie ; Platt, Tracey ; Ruch, Willibald Abstract: This scoping study examines the relation of the sense of humor and three dispositions toward ridicule and being laughed at to psychopathic personality traits. Based on self-reports from 233 adults, psychopathic personality traits were robustly related to enjoying laughing at others, which most strongly related to a manipulative/impulsive lifestyle and callousness. Higher psychopathic traits correlated with bad mood and it existed independently from the ability of laughing at oneself. While overall psychopathic personality traits existed independently from the sense of humor, the facet of superficial charm yielded a robust positive relation. Higher joy in being laughed at also correlated with higher expressions in superficial charm and grandiosity while fearing to be laughed at went along with higher expressions in a manipulative life-style. Thus, the psychopathic personality trait could be well described in its relation to humor and laughter. Implications of the findings are highlighted and discussed with respect to the current literature. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.04.007 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-62966 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Proyer, Rene T; Flisch, Rahel; Tschupp, Stefanie; Platt, Tracey; Ruch, Willibald (2012).