The Elusive Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (LAB) Beneath Cratons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Density Difference Between Subducted Oceanic Crust and Ambient Mantle in the Mantle Transition Zone Density Difference Between S

Density Difference between Subducted Oceanic Crust and Ambient Mantle in the Mantle Transition Zone Since the beginning of plate tectonics, the were packed separately into NaCl or MgO sample oceanic lithosphere has been continually subducted chamber with a mixture of gold and MgO, and into the Earth’s deep mantle for 4.5 Gy. The compressed in the same high-pressure cell. The oceanic lithosphere consists of an upper basaltic pressure was determined by the cell volume for layer (oceanic crust) and a lower olivine-rich gold using an equation of state of gold [2], and the peridotitic layer. The total amount of subducted temperature was measured by a thermocouple. oceanic crust in this 4.5 Gy period is estimated to The cell volumes of garnet and ringwoodite were be at least ~3 × 1 0 23 kg, which is about 8% of the determined by least squares calculations using the weight of the present Earth’s mantle. Thus, the positions of X-ray diffraction peaks. The samples oceanic crust, which is rich in pyroxene and garnet, were compressed to the desired pressure at room may be the source of very important chemical temperature and heated to the maximum temperature heterogeneity in the olivine-rich Earth’s mantle. To to release non-hydrostatic stress. clarify behavior of the oceanic crust in the deep Pressure-volume-temperature data were collected mantle, accurate information about density under 47 different conditions. Figure 1 shows P -V - differences between the oceanic crust and the T data for garnet. The data collected by using an ambient mantle is very important. -

Mantle Transition Zone Structure Beneath Northeast Asia from 2-D

RESEARCH ARTICLE Mantle Transition Zone Structure Beneath Northeast 10.1029/2018JB016642 Asia From 2‐D Triplicated Waveform Modeling: Key Points: • The 2‐D triplicated waveform Implication for a Segmented Stagnant Slab fi ‐ modeling reveals ne scale velocity Yujing Lai1,2 , Ling Chen1,2,3 , Tao Wang4 , and Zhongwen Zhan5 structure of the Pacific stagnant slab • High V /V ratios imply a hydrous p s 1State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and/or carbonated MTZ beneath 2 3 Northeast Asia Beijing, China, College of Earth Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, CAS Center for • A low‐velocity gap is detected within Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, Beijing, China, 4Institute of Geophysics and Geodynamics, School of Earth the stagnant slab, probably Sciences and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 5Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of suggesting a deep origin of the Technology, Pasadena, California, USA Changbaishan intraplate volcanism Supporting Information: Abstract The structure of the mantle transition zone (MTZ) in subduction zones is essential for • Supporting Information S1 understanding subduction dynamics in the deep mantle and its surface responses. We constructed the P (Vp) and SH velocity (Vs) structure images of the MTZ beneath Northeast Asia based on two‐dimensional ‐ Correspondence to: (2 D) triplicated waveform modeling. In the upper MTZ, a normal Vp but 2.5% low Vs layer compared with L. Chen and T. Wang, IASP91 are required by the triplication data. In the lower MTZ, our results show a relatively higher‐velocity [email protected]; layer (+2% V and −0.5% V compared to IASP91) with a thickness of ~140 km and length of ~1,200 km [email protected] p s atop the 660‐km discontinuity. -

Continental Flood Basalts Derived from the Hydrous Mantle Transition Zone

ARTICLE Received 4 Sep 2014 | Accepted 1 Jun 2015 | Published 14 Jul 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8700 Continental flood basalts derived from the hydrous mantle transition zone Xuan-Ce Wang1, Simon A. Wilde1, Qiu-Li Li2 & Ya-Nan Yang2 It has previously been postulated that the Earth’s hydrous mantle transition zone may play a key role in intraplate magmatism, but no confirmatory evidence has been reported. Here we demonstrate that hydrothermally altered subducted oceanic crust was involved in generating the late Cenozoic Chifeng continental flood basalts of East Asia. This study combines oxygen isotopes with conventional geochemistry to provide evidence for an origin in the hydrous mantle transition zone. These observations lead us to propose an alternative thermochemical model, whereby slab-triggered wet upwelling produces large volumes of melt that may rise from the hydrous mantle transition zone. This model explains the lack of pre-magmatic lithospheric extension or a hotspot track and also the arc-like signatures observed in some large-scale intracontinental magmas. Deep-Earth water cycling, linked to cold subduction, slab stagnation, wet mantle upwelling and assembly/breakup of supercontinents, can potentially account for the chemical diversity of many continental flood basalts. 1 ARC Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems (CCFS), The Institute for Geoscience Research (TIGeR), Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth, Western Australia 6845, Australia. 2 State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O.Box9825, Beijing 100029, China. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to X.-C.W. -

D6 Lithosphere, Asthenosphere, Mesosphere

200 Chapter d FAMILIAR WORLD The Present is the Key to the Past: HUGH RANCE d6 Lithosphere, asthenosphere, mesosphere < plastic zone > The terms lithosphere and asthenosphere stem from Joseph Barell’s 1914-15 papers on isostasy, entitled The Strength of the Earth's Crust, in the Journal of Geology.1 In the 1960s, seismic studies revealed a zone of rock weakness worldwide near the top of the upper part of the mantle. This zone of weakness is called the asthenosphere (Gk. asthenes, weak). The asthenosphere turned out to be of revolutionary significance for historical geology (see Topic d7, plate tectonic theory). Within the asthenosphere, rock behaves plastically at rates of deformation measured in cm/yr over lineal distances of thousands of kilometers. Above the asthenosphere, at the same rate of deformation, rock behaves elastically and, being brittle, it can break (fault). The shell of rock above the asthenosphere is called the lithosphere (Gk. lithos, stone). The lithosphere as its name implies is more rigid than the asthenosphere. It is important to remember that the names crust and lithosphere are not synonyms. The crust, the upper part of the lithosphere, is continental rock (granitic) in some places and is oceanic rock (basaltic) elsewhere. The lower part of lithosphere is mantle rock (peridotite); cooler but of like composition to the asthenosphere. The asthenosphere’s top (Figure d6.1) has an average depth of 95 km worldwide below 70+ million year old oceanic lithosphere.2 It shallows below oceanic rises to near seafloor at oceanic ridge crests. The rigidity difference between the lithosphere and the asthenosphere exists because downward through the asthenosphere, the weakening effect of increasing temperature exceeds the strengthening effect of increasing pressure. -

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone Daniel J. Frost* DOI: 10.2113/GSELEMENTS.4.3.171 he upper mantle is the source of almost all magmas. It contains major body wave velocity structure, such as PREM (preliminary reference transitions in rheological and thermal behaviour that control the character Earth model) (e.g. Dziewonski and Tof plate tectonics and the style of mantle dynamics. Essential parameters Anderson 1981). in any model to describe these phenomena are the mantle’s compositional The transition zone, between 410 and thermal structure. Most samples of the mantle come from the lithosphere. and 660 km, is an excellent region Although the composition of the underlying asthenospheric mantle can be to perform such a comparison estimated, this is made difficult by the fact that this part of the mantle partially because it is free of the complex thermal and chemical structure melts and differentiates before samples ever reach the surface. The composition imparted on the shallow mantle by and conditions in the mantle at depths significantly below the lithosphere must the lithosphere and melting be interpreted from geophysical observations combined with experimental processes. It contains a number of seismic discontinuities—sharp jumps data on mineral and rock properties. Fortunately, the transition zone, which in seismic velocity, that are gener- extends from approximately 410 to 660 km, has a number of characteristic ally accepted to arise from mineral globally observed seismic properties that should ultimately place essential phase transformations (Agee 1998). These discontinuities have certain constraints on the compositional and thermal state of the mantle. features that correlate directly with characteristics of the mineral trans- KEYWORDS: seismic discontinuity, phase transformation, pyrolite, wadsleyite, ringwoodite formations, such as the proportions of the transforming minerals and the temperature at the discontinu- INTRODUCTION ity. -

Subduction-Transition Zone Interaction: a Review

Research Paper THEMED ISSUE: Subduction Top to Bottom 2 GEOSPHERE Subduction-transition zone interaction: A review Saskia Goes1, Roberto Agrusta1,2, Jeroen van Hunen2, and Fanny Garel3 1Department of Earth Science & Engineering, Royal School of Mines, Imperial College, London SW7 2AZ, UK GEOSPHERE; v. 13, no. 3 2Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Science Labs, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 3Géosciences Montpellier, Université de Montpellier, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), 34095 Montpellier cedex 05, France doi:10.1130/GES01476.1 9 figures ABSTRACT do not; (2) on what time scales slabs are stagnant in the transition zone if they have flattened; (3) how slab-transition zone interaction is reflected in plate mo- CORRESPONDENCE: s .goes@ imperial .ac .uk As subducting plates reach the base of the upper mantle, some appear tions; and (4) how lower-mantle fast seismic anomalies can be correlated with to flatten and stagnate, while others seemingly go through unimpeded. This past subduction. CITATION: Goes, S., Agrusta, R., van Hunen, J., variable resistance to slab sinking has been proposed to affect long-term ther- Over the past 20 years since the last Subduction Top to Bottom volume and and Garel, F., 2017, Subduction-transition zone inter- action: A review: Geosphere, v. 13, no. 3, p. 1– mal and chemical mantle circulation. A review of observational constraints several reviews of subduction through the transition zone (Lay, 1994; Chris- 21, doi:10.1130/GES01476.1. and dynamic models highlights that neither the increase in viscosity between tensen, 2001; King, 2001; Billen, 2008; Fukao et al., 2009), information about upper and lower mantle (likely by a factor 20–50) nor the coincident endo- the nature of the transition zone and our understanding of how slabs dynami- Received 6 December 2016 thermic phase transition in the main mantle silicates (with a likely Clapeyron cally interact with it has increased substantially. -

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data Walter D. Mooney US Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA, USA Claus Prodehl University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany Nina I. Pavlenkova RAS Institute of the Physics of the Earth, Moscow, Russia 1. Introduction Year Authors Areas covered J/A/B a The purpose of this chapter is to provide a summary of the seismic velocity structure of the continental lithosphere, 1971 Heacock N-America B 1973 Meissner World J i.e., the crust and uppermost mantle. We define the crust as 1973 Mueller World B the outer layer of the Earth that is separated from the under- 1975 Makris E-Africa, Iceland A lying mantle by the Mohorovi6i6 discontinuity (Moho). We 1977 Bamford and Prodehl Europe, N-America J adopted the usual convention of defining the seismic Moho 1977 Heacock Europe, N-America B as the level in the Earth where the seismic compressional- 1977 Mueller Europe, N-America A 1977 Prodehl Europe, N-America A wave (P-wave) velocity increases rapidly or gradually to 1978 Mueller World A a value greater than or equal to 7.6 km sec -1 (Steinhart, 1967), 1980 Zverev and Kosminskaya Europe, Asia B defined in the data by the so-called "Pn" phase (P-normal). 1982 Soller et al. World J Here we use the term uppermost mantle to refer to the 50- 1984 Prodehl World A 200+ km thick lithospheric mantle that forms the root of the 1986 Meissner Continents B 1987 Orcutt Oceans J continents and that is attached to the crust (i.e., moves with the 1989 Mooney and Braile N-America A continental plates). -

Essentials of Geology

INSTRUCTOR’S MANUAL AND TEST BANK Essentials of Geology Fourth Edition Stephen Marshak Instructor’s Manual by John Werner SEMINOLE STATE COLLEGE OF FLORIDA Test Bank by Jacalyn Gorczynski TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY– CORPUS CHRISTI Heather L. Lehto ANGELO STATE UNIVERSITY Daniel Wynne SACRAMENTO COMMUNITY COLLEGE B W • W • NORTON & COMPANY • NEW YORK • LONDON —-1 —0 —+1 5577-50734_ch00_2P.indd77-50734_ch00_2P.indd iiiiii 110/5/120/5/12 55:41:41 PPMM W. W. Norton & Company has been in de pen dent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton fi rst published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The Nortons soon expanded their program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By mid- century, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program— trade books and college texts— were fi rmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today— with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year— W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013, 2009, 2007, 2004 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Associate Editor, Supplements: Callinda Taylor. Project Editor: Thom Foley. Production Manager: Benjamin Reynolds. Editorial Assistant, Supplements: Paula Iborra. Composition and project management: Westchester Publishing Ser vices. Art by CodeMantra and Precision Graphics. -

Controls of Subduction Geometry, Location of Magmatic Arcs, and Tectonics of Arc and Back-Arc Regions

Controls of subduction geometry, location of magmatic arcs, and tectonics of arc and back-arc regions TIMOTHY A. CROSS Exxon Production Research Company, P.O. Box 2189, Houston, Texas 77001 REX H. PILGER, JR. Department of Geology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803 ABSTRACT States), intra-arc extension (for example, convergence rate, direction and rate of the Basin and Range province), foreland absolute upper-plate motion, age of the de- Most variation in geometry and angle of fold and thrust belts, and Laramide-style scending plate, and subduction of aseismic inclination of subducted oceanic lithosphere tectonics. ridges, oceanic plateaus, or intraplate is caused by four interdependent factors. island-seamount chains. It is crucial to Combinations of (1) rapid absolute upper- INTRODUCTION recognize that, in the natural system of the plate motion toward the trench and active Earth, the major factors may interact and, overriding of the subducted plate, (2) rapid Since Luyendyk's (1970) pioneer attempt therefore, are interdependent variables. De- relative plate convergence, and (3) subduc- to relate subduction-zone geometry to some pending on the associations among them, in tion of intraplate island-seamount chains, fundamental aspect(s) of plate kinematics a historical and spatial context, their aseismic ridges, and oceanic plateaus and dynamics, subsequent investigations effects on the geometry of subducted litho- (anomalously low-density oceanic litho- have suggested an increasing variety and sphere can be additive, or by contrast, one sphere) cause low-angle subduction. Under complexity among possible controls and variable can act in opposition to another conditions of low-angle subduction, the resultant configurations of subduction variable and result in total or partial cancel- upper surface of the subducted plate is in zones. -

The Transition-Zone Water Filter Model for Global Material Circulation: Where Do We Stand?

The Transition-Zone Water Filter Model for Global Material Circulation: Where Do We Stand? Shun-ichiro Karato, David Bercovici, Garrett Leahy, Guillaume Richard and Zhicheng Jing Yale University, Department of Geology and Geophysics, New Haven, CT 06520 Materials circulation in Earth’s mantle will be modified if partial melting occurs in the transition zone. Melting in the transition zone is plausible if a significant amount of incompatible components is present in Earth’s mantle. We review the experimental data on melting and melt density and conclude that melting is likely under a broad range of conditions, although conditions for dense melt are more limited. Current geochemical models of Earth suggest the presence of relatively dense incompatible components such as K2O and we conclude that a dense melt is likely formed when the fraction of water is small. Models have been developed to understand the structure of a melt layer and the circulation of melt and vola- tiles. The model suggests a relatively thin melt-rich layer that can be entrained by downwelling current to maintain “steady-state” structure. If deep mantle melting occurs with a small melt fraction, highly incompatible elements including hydro- gen, helium and argon are sequestered without much effect on more compatible elements. This provides a natural explanation for many paradoxes including (i) the apparent discrepancy between whole mantle convection suggested from geophysical observations and the presence of long-lived large reservoirs suggested by geochemical observations, (ii) the helium/heat flow paradox and (iii) the argon paradox. Geophysical observations are reviewed including electrical conductivity and anomalies in seismic wave velocities to test the model and some future direc- tions to refine the model are discussed. -

Phase Transitions in Earth's Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy

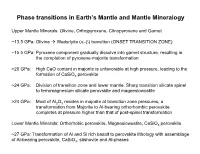

Phase transitions in Earth’s Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy Upper Mantle Minerals: Olivine, Orthopyroxene, Clinopyroxene and Garnet ~13.5 GPa: Olivine Æ Wadsrlyite (DE) transition (ONSET TRANSITION ZONE) ~15.5 GPa: Pyroxene component gradually dissolve into garnet structure, resulting in the completion of pyroxene-majorite transformation >20 GPa: High CaO content in majorite is unfavorable at high pressure, leading to the formation of CaSiO3 perovskite ~24 GPa: Division of transition zone and lower mantle. Sharp transition silicate spinel to ferromagnesium silicate perovskite and magnesiowustite >24 GPa: Most of Al2O3 resides in majorite at transition zone pressures, a transformation from Majorite to Al-bearing orthorhombic perovskite completes at pressure higher than that of post-spinel transformation Lower Mantle Minerals: Orthorhobic perovskite, Magnesiowustite, CaSiO3 perovskite ~27 GPa: Transformation of Al and Si rich basalt to perovskite lithology with assemblage of Al-bearing perovskite, CaSiO3, stishovite and Al-phases Upper Mantle: olivine, garnet and pyroxene Transition zone: olivine (a-phase) transforms to wadsleyite (b-phase) then to spinel structure (g-phase) and finally to perovskite + magnesio-wüstite. Transformations occur at P and T conditions similar to 410, 520 and 660 km seismic discontinuities Xenoliths: (mantle fragments brought to surface in lavas) 60% Olivine + 40 % Pyroxene + some garnet Images removed due to copyright considerations. Garnet: A3B2(SiO4)3 Majorite FeSiO4, (Mg,Fe)2 SiO4 Germanates (Co-, Ni- and Fe- -

Planet Earth in Cross Section by Michael Osborn Fayetteville-Manlius HS

Planet Earth in Cross Section By Michael Osborn Fayetteville-Manlius HS Objectives Devise a model of the layers of the Earth to scale. Background Planet Earth is organized into layers of varying thickness. This solid, rocky planet becomes denser as one travels into its interior. Gravity has caused the planet to differentiate, meaning that denser material have been pulled towards Earth’s center. Relatively less dense material migrates to the surface. What follows is a brief description1 of each layer beginning at the center of the Earth and working out towards the atmosphere. Inner Core – The solid innermost sphere of the Earth, about 1271 kilometers in radius. Examination of meteorites has led geologists to infer that the inner core is composed of iron and nickel. Outer Core - A layer surrounding the inner core that is about 2270 kilometers thick and which has the properties of a liquid. Mantle – A solid, 2885-kilometer thick layer of ultra-mafic rock located below the crust. This is the thickest layer of the earth. Asthenosphere – A partially melted layer of ultra-mafic rock in the mantle situated below the lithosphere. Tectonic plates slide along this layer. Lithosphere – The solid outer portion of the Earth that is capable of movement. The lithosphere is a rock layer composed of the crust (felsic continental crust and mafic ocean crust) and the portion of the mafic upper mantle situated above the asthenosphere. Hydrosphere – Refers to the water portion at or near Earth’s surface. The hydrosphere is primarily composed of oceans, but also includes, lakes, streams and groundwater.