How to Exclude Expectant Mothers from Prosecution for Mere Exposure of HIV to Their Fetuses and Infants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charting a Path Along the Continuum of PMTCT of HIV-1, to Elimination, and Finally to Eradication

EDITORIAL Charting a path along the continuum of PMTCT of HIV-1, to elimination, and finally to eradication In this editorial we traverse the continuum of We stress that much of the hard scientific data on prevention transmission of HIV-1 from mothers to children to and elimination are already available; what is required are health highlight the biomedical history of this problem. service refinements. Eradication demands many more basic science Treatment has progressed from prevention with experiments to confirm the results indicating ‘cure’ in the Mississippi antiretrovirals (ARVs) through to a broader set of baby, and to increase our understanding of the biology of latency interventions, including various breastfeeding options and other health and destruction of the replicative capacity of the virus. We need system improvements, that have increased the possibility of eliminating more information on the cellular and molecular environment of mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) of HIV. At the far end of the the CD4+ memory cells, and specific sites that harbour the virus. continuum, the spectacular findings in the case of the Mississippi Among the prerequisites for eradication are public health studies ‘cured’ baby indicate that eradication is possible. to enable SA to scale up facilities and personnel for very early HIV infections in children are overwhelmingly due to MTCT,[1] intra- diagnosis and treatment. uterine infections accounting for 10 - 25% of cases and intrapartum infections and those through breastfeeding for 35 - 40%. High- and Prevention middle-income countries have had considerable success in preventing Numerous reviews of trials undertaken to prevent MTCT have new HIV infections in children. -

Download The

WHAT ABOUT CONDOMS? CONFERENCE UPDATE: T HE CROI REPORT WHY I RIDE: Ou T AND OPEN IN THE RIDE FOR AIDS CHICAGO POSITIVELY AWARE THE HIV TREATMENT JOURNAL OF TEST POSITIVE AWARE NETWORK MAY+JUNE 2015 T HE BIGGES CHANGES IN 20 YEARS ARE COMING REIn THINK NG HIV NEW APPROACHES TO TREATMENT n CHASING THE CURE n 3D animation OF HIV Client Name: GSK/Triumeq Healthcare This advertisement prepared by: Product: Triumeq Havas Worldwide Job Number: 200 Hudson Street 65013 Filename 65013_58522_M02_DTR045R0_CouchSpread_ Last Modified 1-14-2015 12:41 PM User / PrevUs- Derrick.Edwin / Aileen.Boyce Client GSK Triumeq Art Director M. Culbreth Bleed 16.25” x 10.75” Path Premedia:Volumes:Premedia:Pre- CMYK press:65013_58522:Final:Pre- 0000065013_0000058522_M02_DTR045R0_FCAD – Positively Aware New York, New York 10013 Create 1-14-2015 10:42 AM Artist Kerry Trim 16” x 10.5” press:65013_58522_M02_DTR045R0_ CouchSpread_FCAD-for PREPRESS. Proof Caption: “I have the courage to start HIV…” (Man on Couch) 3 Traffic R. Rodriguez Saftey 15” x 10” indd Fonts Helvetica Neue LT Std (75 Bold, 77 Bold Condensed, 57 Condensed, 55 Roman, 47 Light Condensed, 67 Medium Condensed, 47 Light Condensed Oblique; OpenType), Minion Pro (Regular; OpenType), TT Slug Media: 4/C Magazine Spread + PBW +PBW + ½ PBW AD: M. Culbreth OTF (Regular; OpenType) PAR # DTR045R0 AE: M. Halle Art TRIU_58522_01_CeasarCouchAd_SW_V6_HR.tif (Premedia:Prepress:65013_58522:Original:1.14.15:0000065013_0000058522_M02_DTR045R0_CouchSpread_FCAD Folder:Links:TRIU_58522_01_CeasarCouch- Ad_SW_V6_HR.tif), ViiVHCcmyk.ai (Premedia:Prepress:65013_58522:Original:1.14.15:0000065013_0000058522_M02_DTR045R0_CouchSpread_FCAD Folder:Links:ViiVHCcmyk.ai), Triumeq_US_CMYK_Reg_NEW. Prod: I. Waugh ai (Premedia:Prepress:65013_58522:Original:1.14.15:0000065013_0000058522_M02_DTR045R0_CouchSpread_FCAD Folder:Links:Triumeq_US_CMYK_Reg_NEW.ai), TRIU_58522_02_ItsTimeLogo_SW_V1_130_ B: 16.25” x 10.75” T: 16” x 10.5” Bill Studio Labor OOP to: 0000065013 S: 15” x 10” Gutter Safety = 1” B:16.25” T:16” S:15” TRIUMEQ is a once-a-day pill used to treat HIV-1. -

Study Protocol

RIVER Protocol Version 5.0 20-Oct-2016 GENERAL INFORMATION This document was constructed using the MRC CTU Protocol Template Version 3.0. The MRC CTU endorses the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations For Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) initiative. It describes the RIVER trial, co-ordinated by the Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinical Trials Unit at UCL (herein referred to as MRC CTU), and provides information about procedures for entering participants into it. The protocol should not be used as an aide-memoire or guide for the treatment of other participants. Every care has been taken in drafting this protocol, but corrections or amendments may be necessary. These will be circulated to the registered investigators in the trial, but sites entering participants for the first time are advised to contact RIVER Co-ordinating Centre at, MRC CTU, to confirm they have the most up-to-date version. COMPLIANCE The trial will be conducted in compliance with the approved protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki 1996, the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP), Commission Directive 2005/28/EC with the implementation in national legislation in the UK by Statutory Instrument 2004/1031 and subsequent amendments, the UK Data Protection Act (DPA number: Z6364106), and the National Health Service (NHS) Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care (RGF). SPONSOR Imperial College London is the trial sponsor and has delegated responsibility for the overall management of the RIVER trial to the MRC CTU (RIVER Co-ordinating Centre). Queries relating to Imperial sponsorship of this trial should be addressed to the chief investigator via the Imperial Joint Research Compliance Office. -

What Will It Take to Cure HIV?

IAS–USA Topics in Antiviral Medicine Perspective What Will It Take to Cure HIV? Investigational strategies to attempt HIV cure or remission include very detectable virus during 3 years of treat- early initiation of antiretroviral therapy to limit the latent HIV reservoir and ment but exhibited viral rebound 2 preinfection vaccination. In the setting of viral suppression, strategies include weeks to 3 weeks after stopping treat- reactivation of latently infected cells (eg, through “shock” therapy with ment. Similarly, an HIV-infected baby histone deacetylase inhibitors or other agents); use of broadly neutralizing in Milan began antiretroviral treatment antibodies, therapeutic vaccines, immunotoxins, or other immune-based 12 hours after birth and had no detect- therapies to kill latently infected cells; and gene editing to induce target able virus for 3 years while receiving cell resistance (eg, by eliminating the CC chemokine receptor 5 [CCR5] treatment but exhibited viral rebound 2 coreceptor). Improved ability to detect and quantify very low levels of virus weeks to 3 weeks after stopping treat- is needed. This article summarizes a presentation by Jintanat Ananworanich, ment.5-9 MD, PhD, at the IAS–USA continuing education program held in New York, In general, it is believed that earlier New York, in October 2014. initiation of antiretroviral therapy and the longer it is maintained improve the Keywords: HIV, cure, remission, viral reservoir, latent infection chance of limiting the viral reservoir and achieving HIV remission. How- ever, among the infants who eventually HIV cure research currently focuses 7 months, respectively, after receiv- exhibited rebound after stopping anti- on 2 goals: complete eradication of ing bone marrow transplantation with retroviral therapy, time to viral rebound HIV from the body and HIV remission. -

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection Developed by the HHS Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of Children Living with HIV—A Working Group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC) How to Cite the Pediatric Guidelines: Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of Children Living with HIV. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/content- files/lvguidelines/pediatricguidelines.pdf. Accessed (insert date) [include page numbers, table number, etc. if applicable] Use of antiretrovirals in pediatric patients is evolving rapidly. These guidelines are updated regularly to provide current information.The most recent information is available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov. What’s New in the Pediatric Guidelines (Last updated April 14, 2020; last reviewed April 14, 2020) The Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of Children Living with HIV (the Panel) has reviewed previous versions of the Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection and revised the text and references. Key updates are summarized below. April 14, 2020 When to Initiate Therapy in Antiretroviral-Naive Children • The Panel now recommends rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all children, not just those aged <1 year. Rapid initiation is defined as initiating therapy immediately or within days of HIV diagnosis. • Because the Panel no longer makes recommendations about when to initiate ART based on a child’s age (either <1 year of age or ≥1 year of age), Table A has been deleted and the data that support rapid initiation have been grouped by outcome (i.e., survival and health benefits, neurodevelopmental benefits, immune benefits, and viral reservoirs and viral suppression). -

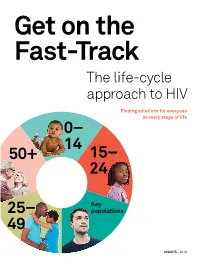

Get on the Fast-Track — the Life-Cycle Approach To

Get on the Fast-Track The life-cycle approach to HIV Finding solutions for everyone at every stage of life 0 – 14 50+ 1 5 – 24 Key 2 5 – populations 49 UNAIDS | 2016 2 contents 1 Foreword 3 2 Introduction 6 3 Children (0–14) 12 4 Young people (15–24) 28 5 Key populations throughout the life cycle 50 6 Adulthood (25–49) 72 7 Ageing (50+) 90 8 Conclusion 101 9 AIDS by the numbers 105 10 Annex on methods 133 2 foreword The scope of HIV prevention and treatment options has never been wider than it is today. The world now has the scientific knowledge and experience to reach people with HIV options tailored to their lives in the communities in which they live. This life-cycle approach to HIV ensures that we find the best solutions for people throughout their lifetime. And it begins with giving children a healthy start in life free from HIV. The progress made in reducing mother-to-child transmission of HIV is one of the remarkable success stories in global health. Antiretroviral medicines have averted 1.6 million new HIV infections among children since 2000. Even so, intensified efforts are needed to virtually eliminate transmis- sion from mother to child. Adolescence is a turbulent time, and a particularly dangerous time for young women living in sub-Saharan Africa. As they transition to adulthood, their risk of becoming infected with HIV increases dramatically. When women and girls are empowered, they have the means to protect themselves from becoming infected with HIV and to access HIV services. -

A Cure for HIV: Where We've Been, and Where We're Headed

Comment A cure for HIV: where we’ve been, and where we’re headed 2013 marks the 30th anniversary of the discovery of HIV.1 reservoirs for HIV, at least in an infant with an immature See Editorial page 2056 30 Years of HIV Science: Imagine the Future, a meeting immune system. Careful follow up and further studies See Review page 2109 at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, in May, 2013, will be needed to see if this approach can be replicated in For more on 30 Years of HIV Science: Imagine the Future see sought to celebrate successes in countering the HIV/AIDS more infants, and then on a larger scale. http://www.30yearshiv.org epidemic and to map out the challenges ahead. In the VISCONTI cohort,6 14 patients in France have The successes have been spectacular. Antiretroviral maintained control of their HIV infection for a median therapy (ART) has transformed what was once a death of 7·5 years after ART interruption.6 These so-called sentence into a chronic manageable disease. ART not only post-treatment controllers were diagnosed and treated prolongs life, but dramatically reduces HIV transmission. with ART during primary HIV infection (on average ART is now available to 8 million people living with within 10 weeks after infection), for a median of 3 years HIV in low-income and middle-income countries.2 In before discontinuation. Patients in this cohort do not 2011, the numbers of new infections declined by 50% have the same distinct immunological profi le seen in 25 countries—many in Africa, which has the largest in elite controllers, who naturally control HIV in the burden of disease.2 These advances are a result of trans- absence of ART.6 The VISCONTI study potentially shows formative science, advocacy, political commitment, and the benefi ts of early ART on the size of the reservoir. -

The Transient HIV Remission in the Mississippi Baby: Why Is This Good

Ananworanich J and Robb ML. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2014, 17:19859 http://www.jiasociety.org/index.php/jias/article/view/19859 | http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19859 Viewpoint The transient HIV remission in the Mississippi baby: why is this good news? Jintanat Ananworanich§,1,2 and Merlin L Robb1,2 §Corresponding author: Jintanat Ananworanich, U.S. Military HIV Research Program, 6720A Rockledge Drive, Suite 400, Bethesda, MD 20817, USA. Tel: 301 500 3949, Fax: 301 500 3666. ([email protected]) Received 10 October 2014; Accepted 21 October 2014; Published 20 November 2014 Copyright: – 2014 Ananworanich J and Robb ML; licensee International AIDS Society. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. As researchers, clinicians and community advocates gathered they had no detectable HIV viremia or cell associated HIV DNA for the 20th International AIDS Society meeting in Melbourne but the viral load rebounded in 3 months in one patient and in July of this year, the announcement of resumption of viremia 7 months in the other after ART was stopped [3]. in the Mississippi baby came as an unwelcome surprise. The Recently, Canadian researchers presented a case that was case had previously stirred excitement that a cure was possible treated within the first 24 hours of life and was on ART for without the extreme measure of bone marrow transplanta- 3 years before treatment was interrupted. -

Mississippi Baby Media Coverage

Mississippi Baby Media Coverage 1. The Guardian 2. New Scientist 3. BBC News Health 4. AFP 5. Reuters 6. AP 7. The New York Times 8. The Washington Post 9. Los Angeles Times 10. Nature 11. Science News 12. Channel 4 13. NRP 14. Le Monde 15. France 24 16. RFI 17. Liberation 18. ABC 19. CNN 20. NBC 1 The Guardian US doctors cure child born with HIV Mississippi doctors make medical history made with first 'functional cure' of unnamed two-year-old born with the virus who now needs no medication Doctors in the US have made medical history by effectively curing a child born with HIV, the first time such a case has been documented. The infant, who is now two and a half, needs no medication for HIV, has a normal life expectancy and is highly unlikely to be infectious to others, doctors believe. Though medical staff and scientists are unclear why the treatment was effective, the surprise success has raised hopes that the therapy might ultimately help doctors eradicate the virus among newborns. Doctors did not release the name or sex of the child to protect the patient's identity, but said the infant was born, and lived, in Mississippi state. Details of the case were unveiled on Sunday at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Atlanta. Dr Hannah Gay, who cared for the child at the University of Mississippi medical centre, told the Guardian the case amounted to the first "functional cure" of an HIV-infected child. A patient is functionally cured of HIV when standard tests are negative for the virus, but it is likely that a tiny amount remains in their body. -

MANDATORY HIV TESTING of PREGNANT WOMEN: PUBLIC HEALTH OR PRIVACY VIOLATION? Anna Lozoya, J.D., RN*

LOZOYA-FINAL(UPDATED) (DO NOT DELETE) 10/14/2016 10:16 AM 16 Hous. J. Health L. & Policy 77 Copyright © 2016 Anna Lozoya Houston Journal of Health Law & Policy MANDATORY HIV TESTING OF PREGNANT WOMEN: PUBLIC HEALTH OR PRIVACY VIOLATION? Anna Lozoya, J.D., RN* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 78 I. NATIONAL GUIDELINES .......................................................................... 81 II. A WOMAN’S AUTONOMY AND RIGHT TO PRIVACY .............................. 84 A. Privacy ...................................................................................... 85 B. Right to Refuse Medical Treatment ...................................... 85 C. The Rights of the Unborn ...................................................... 88 D. A Pregnant Woman’s Right to Refuse Medical Treatment ................................................................................. 92 E. Damages for Injuries in Utero ............................................... 97 III. LEGAL DOCTRINES ................................................................................ 98 A. Special Needs .......................................................................... 99 B. Parens Patriae ........................................................................ 101 IV. HIV TESTING STATUTES ..................................................................... 104 A. California’s Statute ............................................................... 105 V. RECENT SCIENTIFIC -

Twelve Recommendations Following a Discussion About the ‘Mississippi Baby’

Meeting Report Durban, South Africa | 3–4 June 2013 Twelve recommendations following a discussion about the ‘Mississippi baby’ Implications for public health programmes to eliminate new HIV infections among children GLOSSARY OF TERMS ANC Antenatal care ART Antiretroviral treatment AZT Zidovudine CAPRISA Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa CHER Children with HIV early antiretroviral therapy DBS Dried blood spot EID Early infant diagnosis FTC Emtricitabine IMPAACT International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group IRD Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement LPV/r Lopinavir/ritonavir NHLS National Health Laboratory Services NIH National Institutes for Health NVP Nevirapine PCR Polymerase chain reaction PHPT Program for HIV Prevention and Treatment (Thailand) PK Pharmacokinetics PMTCT Prevention of mother-to-child transmission POC Point-of-care RAL Raltegravir TB Tuberculosis TDF Tenofovir 3TC Lamivudine WHO World Health Organization UNAIDS / JC2531/1/E This paper was commissioned by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). However the views expressed in the paper/report are the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of UNAIDS or its Cosponsors. Unless otherwise indicated photographs used in this document are used for illustrative purposes only. Unless indicated, any person depicted in the document is a “model”, and use of the photograph does not indicate endorsement by the model of the content of this document nor is there any relation between the model and any of the topics covered in this document. RECOMMENDATIONS Twelve recommendations following a discussion about the ‘Mississippi baby’ | UNAIDS / CAPRISA 1 RECOMMENDATIONS At the meeting on Scientific Advances from the ‘Mississippi baby’: Implications for public health programmes to eliminate new HIV infections among children, hosted at the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) in Durban, participants agreed on 12 recommendations to help reach the goal of eliminating new HIV infections among children. -

AIDS.Gov 30 Years of HIV/AIDS Timeline

A TIMELINE OF HIV/AIDS • June 5: The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and an article entitled “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Prevention (CDC) publish a Morbidity and Mortality Homosexuals.” At this point, the term “gay cancer” 1981 Weekly Report (MMWR), describing cases of a rare enters the public lexicon. lung infection, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia • September 21: The nation’s first Kaposi’s Sarcoma (PCP), in five young, previously healthy, gay men clinic opens at the University of California, San in Los Angeles. All the men have other unusual Francisco Medical Center. infections as well, indicating that their immune systems are not working; two have already died by • December 10: Bobbi Campbell, a San Francisco the time the report is published. This edition of the nurse, becomes the first KS patient to go public. MMWR marks the first official reporting of what will Calling himself the “KS Poster Boy,“ Campbell writes become known as the AIDS epidemic. a newspaper column on living with “gay cancer” for the San Francisco Sentinel. He also posts photos • June 5-6: The Associated Press, the Los Angeles of his lesions in the window of a local drugstore to Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle report alert the community to the disease and encourage on the MMWR article. Within days, CDC receives people to seek treatment. numerous reports of similar cases of PCP and other opportunistic infections among gay men—including • By year’s end, there is a cumulative total of 270 reports of a cluster of cases of a rare, and unusually reported cases of severe immune deficiency among aggressive, cancer, Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS), among a gay men, and 121 of those individuals have died.