Paul Nash's 'Landscape at Iden'*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POEMS for REMEMBRANCE DAY, NOVEMBER 11 for the Fallen

POEMS FOR REMEMBRANCE DAY, NOVEMBER 11 For the Fallen Stanzas 3 and 4 from Lawrence Binyon’s 8-stanza poem “For the Fallen” . They went with songs to the battle, they were young, Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them. Robert Laurence Binyon Poem by Robert Laurence Binyon (1869-1943), published in by the artist William Strang The Times newspaper on 21st September 1914. Inspiration for “For the Fallen” Laurence Binyon composed his best-known poem while sitting on the cliff-top looking out to sea from the dramatic scenery of the north Cornish coastline. The poem was written in mid-September 1914, a few weeks after the outbreak of the First World War. Laurence said in 1939 that the four lines of the fourth stanza came to him first. These words of the fourth stanza have become especially familiar and famous, having been adopted as an Exhortation for ceremonies of Remembrance to commemorate fallen service men and women. Laurence Binyon was too old to enlist in the military forces, but he went to work for the Red Cross as a medical orderly in 1916. He lost several close friends and his brother-in-law in the war. . -

Paper 4, Module 17: Text

Paper 4, Module 17: Text Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator Prof. Hariharan Institute of English, University of Balagovindan Kerala Content Writer/Author Dr. Milon Franz St. Xavier’s College, Aluva (CW) Content Reviewer (CR) Dr. Jameela Begum Former Head & Professor, Institute of English, University of Kerala Language Editor (LE) Prof. Hariharan Institute of English, University of Balagovindan Kerala 2 War Poets. Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke Introduction War poetry is set in contrast with Georgian poetry, the poetry that preceded it. While the Georgian poets presented war as a noble affair, celebrating ‘the happy warrior’ proud to give his life for his country, the war poets chose to represent the horror and ‘pity’ of war. War poetry was actually anti-war poetry, an indictment of the whole ideology of the nobleness of war. For war poets, war was an unnatural, meaningless, foolish and brutal enterprise in which there is nothing honourable, glorious, or decorous. It was a kind of modern poetry which is naturalistic and painfully realistic, with shocking images and language, intending to show what the war is really like. They tried to portray the common experience on the war front which constitutes mortality, nervous breakdown, constant fear and pressure. The war poetry is replete with the mud, the trenches, death, and the total havoc caused by war. Wilfred Owen wrote: ‘Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of war’. 1. War Poetry War poetry encompasses the poetry written during and about the First World War. -

THE ENDURING IMPACT of the FIRST WORLD WAR a Collection of Perspectives

THE ENDURING IMPACT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR A collection of perspectives Edited by Gail Romano and Kingsley Baird ‘That Huge, Haunted Solitude’: 1917–1927 A Spectral Decade Paul Gough Arts University Bournemouth Abstract The scene that followed was the most remarkable that I have ever witnessed. At one moment there was an intense and nerve shattering struggle with death screaming through the air. Then, as if with the wave of a magic wand, all was changed; all over ‘No Man’s Land’ troops came out of the trenches, or rose from the ground where they had been lying.1 In 1917 the British government took the unprecedented decision to ban the depiction of the corpses of British and Allied troops in officially sponsored war art. A decade later, in 1927, Australian painter Will Longstaff exhibited Menin Gate at Midnight which shows a host of phantom soldiers emerging from the soil of the Flanders battlegrounds and marching towards Herbert Baker’s immense memorial arch. Longstaff could have seen the work of British artist and war veteran Stanley Spencer. His vast panorama of post-battle exhumation, The Resurrection of the Soldiers, begun also in 1927, was painted as vast tracts of despoiled land in France and Belgium were being recovered, repaired, and planted with thousands of gravestones and military cemeteries. As salvage parties recovered thousands of corpses, concentrating them into designated burial places, Spencer painted his powerful image of recovery and reconciliation. This article will locate this period of ‘re-membering’ in the context of such artists as Will Dyson, Otto Dix, French film-maker Abel Gance, and more recent depictions of conflict by the photographer Jeff Wall. -

A Masonic Minute M.W

A Masonic Minute M.W. Bro. Raymond S. J. Daniels VIMY – LEST WE FORGET Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends. John 15: 13 ‘Lest we forget’ Out of the horrors of war comes some of the most inspired and evocative poetry in the English language? As we commemorate the centenary of The Great War– The War to end War (1914- 1918) – now known as World War I, in this Month of Remembrance, these poems help us to reflect and transform history into a personal experience. These poems articulate our inexpressible feelings when we are lost for words. A poem by Sir John Stanhope Arkwright (1872–1954), published in The Supreme Sacrifice, and other Poems in Time of War (1919), embodies the essence of Remembrance – honour and self- sacrifice. It was set to music by the Rev. Dr. Charles Harris, Vicar of Colwall, Herefordshire (1909-1929) and is frequently sung at cenotaph services. O valiant hearts who to your glory came Through dust of conflict and through battle flame; Tranquil you lie, your knightly virtue proved, Your memory hallowed in the land you loved. Proudly you gathered, rank on rank, to war As who had heard God’s message from afar; All you had hoped for, all you had, you gave, To save mankind—yourselves you scorned to save. Splendid you passed, the great surrender made; Into the light that nevermore shall fade; Deep your contentment in that blest abode, Who wait the last clear trumpet call of God. Hanging in many lodge rooms throughout this jurisdiction are engraved plaques and Honour Rolls list the names of those young Masons who served King and Country and paid the Supreme Sacrifice. -

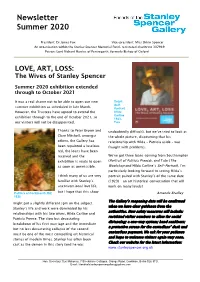

Newsletter Summer 2020

Newsletter Summer 2020 President: Dr James Fox Vice-president: Miss Shirin Spencer An organisation within the Stanley Spencer Memorial Fund, registered charity no 307989 Patron: Lord Richard Harries of Pentregarth, formerly Bishop of Oxford LOVE, ART, LOSS: The Wives of Stanley Spencer Summer 2020 exhibition extended through to October 2021 It was a real shame not to be able to open our new Detail: Self- summer exhibition as scheduled in late March. Portrait, However, the Trustees have agreed to extend the Hilda Carline exhibition through to the end of October 2021, so 1923, our visitors will not be disappointed. Tate Thanks to Peter Brown and undoubtedly difficult), but we’ve tried to look at Clare Mitchell, amongst the whole picture, discovering that his others, the Gallery has relationship with Hilda – Patricia aside – was been repainted a luscious fraught with problems. red, the loans have been received and the We’ve got three loans coming from Southampton exhibition is ready to open (Portrait of Patricia Preece), and Tate (The as soon as permissible. Woolshop and Hilda Carline’s Self-Portrait). I’m particularly looking forward to seeing Hilda’s I think many of us are very portrait paired with Stanley’s of the same date familiar with Stanley’s (1923) – an art historical conversation that will unconventional love life, work on many levels! Patricia at Cockmarsh Hill, but I hope that this show Amanda Bradley 1935 The Gallery’s reopening date will be confirmed might put a slightly different spin on the subject. when we have clear guidance from the Stanley’s life and work were dominated by his authorities. -

China Question of US-American Imagism

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 5 Article 12 China Question of US-American Imagism Qingben Li Hangzhou Normal Universy Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities -

Paper 4 Romanticism: the French Revolution and After And

Paper IV Unit I Romanticism: The French Revolution and After and Romantic Themes 1.1. Introduction During the second half of the 18th century economic and social changes took place in England. The country went through the so-called Industrial Revolution when new industries sprang up and new processes were applied to the manufacture of traditional products. During the reign of King George III (1760-1820) the face of England changed. The factories were built, the industrial development was marked by an increase in the export of finished cloth rather than of raw material, coal and iron industries developed. Internal communications were largely funded. The population increased from 7 million to 14 million people. Much money was invested in road- and canal-building. The first railway line which was launched in 1830 from Liverpool to Manchester allowed many people inspired by poets of Romanticism to discover the beauty of their own country. Just as we understand the tremendous energizing influence of Puritanism in the matter of English liberty by remembering that the common people had begun to read, and that their book was the bible, so we may understand this age of popular government by remembering that the chief subject of romantic literature was the essential nobleness of common men and the value of the individual. As we read now that brief portion of history which lies between the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the English Reform Bill of 1832, we are in the presence of such mighty political upheavals that “the age of revolution” is the only name by which we can adequately characterize it. -

Art of the Great War Zack Deyoung Ouachita Baptist University

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita History Class Publications Department of History 12-18-2014 Art of the Great War Zack Deyoung Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Deyoung, Zack, "Art of the Great War" (2014). History Class Publications. 41. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history/41 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DeYoung 1 Zack DeYoung Dr. Hicks World at War 18 December 2014 Art of the Great War World War One was a major turning point in the history of the world. War advancements had created a monster that no one was ready for. No longer was war seen as glorious, but instead horrifying. Often, the world sees the war from an outside perspective understanding that it was a great tragedy, but they do not understand it from a personal level. Many historians have tried to accomplish this through interviews with the survivors, writing biographies, excavating battle grounds, and various other methods. One method, which is often times overlooked, is viewing the war through the lens of the art pieces produced from it. Some may believe that this is trivial when studying the war but the opposite is true. Art is a reflection of one’s very self; there are few other methods quite as personal as viewing art. -

THE ART of Asia."

TRINiTY COIL llBRAR.Y M.OORE COLLECTION RELATING TO THE FA~ EAST --- ·\..o-· CLASS NO. __ BOOK NO.- VOLU ME-_____,~ ACCESSION NO. THE CHINA SOCIETY LAVRENCE BI~ON THE _A_RT OF ASIA A Paper Tead at a Joint Meeting of the China Society and the .Japa1t Society, held at Caxton Hall, mt Wednesday, No,ember 24, 1915 LONDON: MCMXYI THE ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY-FIRST ORDINARY MEETING (BEING THE FIRST OF THE TWENTY-FIFTH SESSION) Held in the Hall at 20 Hanover Square, W., on Wednesday, the 24th of November, 1915. t At a Joint Meeting of the Japan Society apd the China Society, H.E. the JAPANESE AMBASSADOR in the Chair, Mr. LAURENCE BINYON delivered a lecture on "THE ART OF AsiA." VOL. XIV. B 2 THE ART OF ASIA. By LAURENCE BrNYON, Esq. THOSE of us who are interested in Oriental art have generally approached the subject from the standpoint of one particular country. At this joint meeting of the Japan and China Societies, it may perhaps be an appropriate moment for trying to see the arts of those two countries in their historical setting and background. In this lecture I want to give you some general idea of the art of Asia. It is a vast theme, as vast perhaps as the art of Europe. In the course of an hour I cannot attempt more than the briefest outline; and you will perhaps condemn my rashness in attempting so much as that. But even in this brief space it may, I think, be possible to indicate something of the diverse elements which have formed the character of Asiatic art; to emphasize what is typical in the genius of the art of India, of Persia, of China, and Japan; to note the relation in which the arts of these countries stand to one another. -

Laurence Binyon and the Belgian Artistic Scene: Unearthing Unknown Brotherhoods

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Laurence Binyon and the Belgian Artistic Scene: Unearthing Unknown Brotherhoods Marysa Demoor and Frederick Morel On September 11, 2008, at 10:11am, at a New York City ceremony honouring victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, New York former mayor Rudy Giuliani concluded his speech with a quote from the poem ―For the Fallen.‖ Mr. Giuliani spoke the words with a certain flair, respecting the cadence, stressing the right words, and honouring the pauses: They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them.1 ―For seven years,‖ Mr. Giuliani continued, ―we‘ve come back here to be together, to feel how the entire world is linked in our circle of sorrow. And mostly to remember, those we lost, who are never lost. The poem reminds us how brightly their memories burn.‖2 Ever since Laurence Binyon wrote these four lines in north Cornwall in 1914, they have been recited annually at Remembrance Sunday services worldwide, and people will keep on doing so to commemorate tragic events, even those still to come because they capture the right feelings unerringly. But, ironically, if the lines have become immortal and they are there to commemorate the dead, their author, Laurence Binyon, is all too often unknown. Binyon, poet and art historian, was born in Lancaster on the 10th of August, 1869, to an Anglican clergyman, Frederick Binyon, and his wife Mary. -

Stanley Spencer's 'The Resurrection, Cookham': a Theological

Stanley Spencer’s ‘The Resurrection, Cookham’: A Theological Commentary Jessica Scott “The Resurrection, Cookham”, in its presentation of an eschatology which begins in the here and now, embeds a message which speaks of our world and our present as intimately bound with God for eternity. This conception of an eternal, connecting relationship between Creator and creation begins in Spencer’s vision of the world, which leads him to a view of God, which in turn brings him back to himself. What emerges as of ultimate significance is God’s giving of God’s self. Truth sees God, wisdom beholds God, and from these two comes a third, a holy wondering delight in God, which is love1 It seems that Julian of Norwich’s words speak prophetically of Spencer’s artistic journey - a journey which moves from seeing, to beholding, to joy. Both express love as the essential message of their work. Julian understood her visions as making clear that for God ‘love was his meaning’. Spencer, meanwhile, described his artistic endeavour as invigorated by love, as art’s ‘essential power’. This love, for both, informs the whole of life. God, in light of the power of love, cannot be angry. Julian conceived of sin as something for which God would not blame us. Likewise, Spencer’s Day of Judgement is lacking in judgement. Humanity, in light of the power of love, should not despise itself, not even the bodily self so frequently derided. This love of self finds expression in Julian’s language – she uses ‘sensuality’ when referring to the body.2 Rather than compartmentalising flesh in disregard for it, she 1 Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love, Chapter 44. -

Nash, Nevinson, Spencer, Gertler, Carrington, Bomberg: a Crisis of Brilliance, 1908 – 1920 Dulwich Picture Gallery 12 June – 22 September 2013

Nash, Nevinson, Spencer, Gertler, Carrington, Bomberg: A Crisis of Brilliance, 1908 – 1920 Dulwich Picture Gallery 12 June – 22 September 2013 David Bomberg (1890 – 1957) David Bomberg, Racehorses, 1913, black chalk and wash on paper, 42 x 67 cm, Ben Uri, The London Jewish Museum of Art © The Estate of David Bomberg, All Right Reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, Sappers Under Hill 60, 1919, pencil, ink and wash, 12 x 16 cm, Ben Uri, The London Jewish Museum of Art © The Estate of David Bomberg, All Right Reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, Circus Folk, 1920, oil on paper, 42 x 51.5cm, UK Government Art Collection, © Estate of David Bomberg. All rights reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, In the Hold, 1913-14, oil on canvas, 196.2 x 231.1 cm, © Tate, London 2012 David Bomberg, David Bomberg [self-portrait], c. 1913-14, black chalk, 55.9 x 38.1 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London. © The Estate of David Bomberg. All rights reserved, DACS 2012 David Bomberg, Bathing Scene, c.1912‑13, oil on wood, 55.9 x 68.6cm, © Tate, London 2012 David Bomberg, Study for 'Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St Eloi', 1918-19, oil on canvas, 304.2 x 243.8 cm, ©Tate, London 2012 Dora Carrington (1893 - 1932) Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey, 1916, oil on panel, 50.8 x 60.9 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London Dora Carrington, Mark Gertler, c. 1909-11, pencil on paper, 41.9 x 31.8 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London Dora Carrington, Dora Carrington, c. 1910, pencil on paper, 22.8 x 15.2 cm, © National Portrait Gallery, London Dora