Offences Against the Person a Scoping Consultation Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Law Exam Notes

SUBJECT: CRIMINAL LAW Assault Common Assault • Assault is: • any act committed intentionally or recklessly • that causes another person • to apprehend immediate and unlawful violence → Fagan, Venna • Section 61 → sets out maximum punishment, 2 years imprisonment Actus Reus • Unlawful contact in applying force to another • Note → spitting at and contacting another with spit will constitute assault: Smith; DPP v JWH • The act of creating fear of immediate unlawful contact • Victim must actually be put in fear → Kuhl • The harm threatened must be sufficiently imminent → Zanker v Vartzokas; Knight • Assault can be committed by telephone if sufficiently imminent → Barton v Armstrong; Knight • It is unnecessary that force be accompanied by hostility → Boughey • Mere touching can amount to an assault → Collins v Wilcock • D may be relieved of liability on other grounds, such as: • Lack of mens rea • Implied consent, for example, contact during ordinary social intercourse → Boughey • Use of lawful force, such as self-defence • Victim’s state of mind: • Must actually fear → Kuhl • Must be aware → Pemble (rifle to the back) • Reasonable fear → Barton v Armstrong • Defendant aware of unusual timidity → unreasonableness of fear may not prevent conviction → MacPherson • Imminence: • Fear must be imminent although ‘immediate and continuing‘ can suffice → Zanker v Vartzokas • Threats of future violence not assault → Knight • Examples: • Where D was in another room → Lewis • Where D was on other side of locked door about to force entry → Beech • Where D -

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, 'The Failure of Criminal Law To

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, ‘The Failure of Criminal Law to Control the Use of Off Balance Sheet Finance During the Banking Crisis’ (2015) 36 The Company Lawyer, Issue 4, 99, reproduced with permission of Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd. This extract is taken from the author’s original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/document?&srguid=i0ad8289e0000014eca3cbb3f02 6cd4c4&docguid=I83C7BE20C70F11E48380F725F1B325FB&hitguid=I83C7BE20C70F11 E48380F725F1B325FB&rank=1&spos=1&epos=1&td=25&crumb- action=append&context=6&resolvein=true THE FAILURE OF CRIMINAL LAW TO CONTROL THE USE OF OFF BALANCE SHEET FINANCE DURING THE BANKING CRISIS Dr Stephen Copp & Alison Cronin1 30th May 2014 Introduction A fundamental flaw at the heart of the corporate structure is the scope for fraud based on the provision of misinformation to investors, actual or potential. The scope for fraud arises because the separation of ownership and control in the company facilitates asymmetric information2 in two key circumstances: when a company seeks to raise capital from outside investors and when a company provides information to its owners for stewardship purposes.3 Corporate misinformation, such as the use of off balance sheet finance (OBSF), can distort the allocation of investment funding so that money gets attracted into less well performing enterprises (which may be highly geared and more risky, enhancing the risk of multiple failures). Insofar as it creates a market for lemons it risks damaging confidence in the stock markets themselves since the essence of a market for lemons is that bad drives out good from the market, since sellers of the good have less incentive to sell than sellers of the bad.4 The neo-classical model of perfect competition assumes that there will be perfect information. -

Forgery Act, 1913. [3 & 4 GEO

Forgery Act, 1913. [3 & 4 GEO. 5.Cu. 27.] ARRANGEMENTOF SECTIONS. Section. 1.Definition of forgery. 2.Forgeryof certain documents with intent to defraud. Forgeryof certain documents with intent to defraud or deceive. 4.Forgery of other documents with intent to defraud or to deceive a misdemeanour. 5.Forgery of seals and dies. 6.Uttering. 7.Demanding property on forged documents, &c. 8. Possession of forged documents, seals, and dies. 9.Making or having in possession paper or implements for forgery. 10.Purchasing or having in possession certain paper before it has been duly stamped and issued. 11.Accessories and abettors. 12.Punishments. 13.Jurisdiction of quarter sessions in England. 14.Venue. 15.Criminal possession. 16.Search warrants. 17.Form of indictment and proof of intent. 18.Interpretation. 19.Savings. 20.Repeals. 21.Extent. 22.Short title and commencement. SChEDULE. A [3 & 4 GEO. 5.] Forgery Act, 1913. [Cii. 27.] CHAPTER 27. An Act to consolidate, simplify, and amend the Law A;D. 1913. relating to Forgery and kindred Offences. — [15th August 1913.] it enacted by the King's most Excellent Majesty, by and 1BE—' with the advice of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows: 1.—(1) For the purposes of this Act, forgery is the making Definition of of a false document in order that it may be used as genuine, forgery. and in the case of the seals and dies mentioned in this Act the counterfeiting of a seal or die, and forgery with intent to defraud or deceive, as the case may be, is punishable as in this Act provided. -

Lesley Klaff (PDF)

Presented at International Study Group Education and Research on Antisemitism Colloquium I: Aspects of Antisemitism in the UK 5 December 2009, London Lesley Klaff Anti-Semitism on Campus Summary Lesley's presentation considered the role of the university historically in promoting classical anti-Semitism and its current role in promoting contemporary anti-Semitism. She made the connection between anti-Zionist rhetoric and anti- Semitic hate speech. She argued that the proliferation of anti-Zionist rhetoric on UK campuses in recent years, emboldened by the UCU's annual calls for discriminatory measures against Israel, cannot be supported by the 'free speech' or 'academic freedom' justification, and that the university authorities have both a legal and moral duty to prohibit it. In this context she considered the documented harms to minority students of on-campus hate speech and the legislative context of hate speech with particular reference to hostile environment harassment. She also looked at the ways in which anti-Zionist rhetoric on campus flouts university Equality and Diversity and anti-harassment policies. Anti-Semitism on Campus A Modern Perspective Structure The university and classical anti-Semitism The university and contemporary anti-Semitism Some phenomenological experiences Discussion and Conclusion Anti-Semitism on Campus: Nothing New Wilhelm Marr (1819-1904): attempted to put traditional religion based hatred of Jews on a scientific footing - appeal to modernity’s preference for epistemological criteria. Firm theoretical basis for anti-Semitic discourses – religious justification replaced by an objective “scientific” justification. “Aryan Science” - racial theories of late 19th and early 20th century made their mark on universities and faculties. -

The Law Handbook YOUR PRACTICAL GUIDE to the LAW in NEW SOUTH WALES

The Law Handbook YOUR PRACTICAL GUIDE TO THE LAW IN NEW SOUTH WALES 15th EDITION REDFERN LEGAL CENTRE PUBLISHING 01_Title_piii-iii.indd 3 28-Nov-19 08:08:13 Published in Sydney by Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia Limited ABN 64 058 914 668 19 Harris Street, Pyrmont NSW 2009 First edition published by Redfern Legal Centre as The Legal Resources Book (NSW) in 1978. First published as The Law Handbook in 1983 Second edition 1986 Third edition 1988 Fourth edition 1991 Fifth edition 1995 Sixth edition 1997 Seventh edition 1999 Eighth edition 2002 Ninth edition 2004 Tenth edition 2007 Eleventh edition 2009 Twelfth edition 2012 Thirteenth edition 2014 Fourteenth edition 2016 Fifteenth edition 2019 Note to readers: While every effort has been made to ensure the information in this book is as up to date and as accurate as possible, the law is complex and constantly changing and readers are advised to seek expert advice when faced with specific problems. The Law Handbook is intended as a guide to the law and should not be used as a substitute for legal advice. ISBN: 9780455243689 © 2020 Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia Limited asserts copyright in the compilation of the work and the authors assert copyright in their individual chapters. This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. -

Forgery Act 1861

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally enacted). Forgery Act 1861 1861 CHAPTER 98 An Act to consolidate and amend the Statute Law of England and Ireland relating; to indictable Offences by Forgery. [6th August 1861] WHEREAS it is expedient to consolidate and amend the Statute Law of England and Ireland relating to indictable Offences by Forgery : Be it enacted by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the Authority of the same, as follows : As to forging Her Majesty's Seals :— 1 Forging the Great Seal, Privy Seal, &c. Whosoever shall forge or counterfeit, or shall utter, knowing the same to be forged or counterfeited, the Great Seal of the United Kingdom, Her Majesty's Privy Seal, any Privy Signet of Her Majesty, Her Majesty's Royal Sign Manual, any of Her Majesty's Seals appointed by the Twenty-fourth Article of the Union between England and Scotland to be kept, used, and continued in Scotland, the Great Seal of Ireland, or the Privy Seal of Ireland, or shall forge or counterfeit the Stamp or Impression of any of the Seals aforesaid, or shall utter any Document or Instrument whatsoever, having thereon or affixed thereto the Stamp or Impression of any such forged or counterfeited Seal, knowing the same to be the Stamp or Impression of such forged or counterfeited Seal, or any forged or counterfeited Stamp or Impression made or apparently intended to resemble the Stamp or Impression of any of the Seals aforesaid, knowing the same to be forged or counterfeited, or shall forge or alter, or utter knowing the same to be forged or altered, any Document or Instrument having any of the said Stamps or Impressions thereon or affixed thereto, shall be guilty of Felony, and being convicted thereof shall be liable, at the Discretion of the Court, to be kept in Penal Servitude for Life or for any Term not less than Three Years,—or to be imprisoned for any Term 2 Forgery Act 1861 (c. -

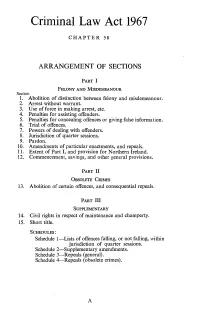

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Bail Act, 1997 ———————— Arrangement of Secti

ÐÐÐÐÐÐÐÐ Number 16 of 1997 ÐÐÐÐÐÐÐÐ BAIL ACT, 1997 ÐÐÐÐÐÐÐÐ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Interpretation. 2. Refusal of bail. 3. Renewal of bail application. 4. Evidence of previous criminal record. 5. Payment of moneys into court, etc. 6. Conditions of bail. 7. Sufficiency of bailspersons. 8. Endorsement on warrants as to release on bail. 9. Estreatment of recognisance and forfeiture of moneys paid into court. 10. Amendment of Criminal Justice Act, 1984. 11. Amendment of Act of 1967. 12. Repeals. 13. Short title and commencement. SCHEDULE ÐÐÐÐÐÐÐÐ [No. 16.] Bail Act, 1997. [1997.] Acts Referred to Air Navigation and Transport Act, 1973 1973, No. 29 Air Navigation and Transport Act, 1975 1975, No. 9 Criminal Damage Act, 1991 1991, No. 31 Criminal Justice (Public Order) Act, 1994 1994, No. 2 Criminal Justice Act, 1984 1984, No. 22 Criminal Justice Act, 1994 1994, No. 15 Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935 1935, No. 6 Criminal Law (Jurisdiction) Act, 1976 1976, No. 14 Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act, 1990 1990, No. 32 Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993 1993, No. 20 Criminal Procedure Act, 1967 1967, No. 12 Defence Act, 1954 1954, No. 18 Explosive Substances Act, 1883 46 & 47 Vict. c. 3 Firearms Act, 1925 1925, No. 17 Firearms Act, 1964 1964, No. 1 Firearms and Offensive Weapons Act, 1990 1990, No. 12 Forgery Act, 1861 1861, c. 98 Forgery Act, 1913 1913, c. 27 Larceny Acts, 1916 to 1990 Misuse of Drugs Act, 1977 1977, No. 12 Offences against the Person Act, 1861 1861, c. 100 Offences against the State Act, 1939 1939, No. -

Theft Act 1968

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Theft Act 1968. (See end of Document for details) Theft Act 1968 1968 CHAPTER 60 General and consequential provisions 2 Theft Act 1968 (c. 60) SCHEDULE 2 – Miscellaneous and Consequential Amendments Document Generated: 2021-04-11 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Theft Act 1968. (See end of Document for details) SCHEDULES X1SCHEDULE 2 Section 33(1),(2). MISCELLANEOUS AND CONSEQUENTIAL AMENDMENTS Editorial Information X1 The text of Schedule 2 is in the form in which it was originally enacted: it was not reproduced in Statutes in Force and, except as specified, does not reflect any amendments or repeals which may have been made prior to 1.2.1991. F1 PART I Textual Amendments F1 Sch. 2 Pt. I repealed (26.3.2001) by S.I. 2001/1149, art. 3(2), Sch. 2 (with art. 4(11)) . 1 The Post Office Act 1953 shall have effect subject to the amendments provided for by this Part of this Schedule (and, except in so far as the contrary intention appears, those amendments have effect throughout the British postal area). 2 Sections 22 and 23 shall be amended by substituting for the word “felony” in section 22(1) and section 23(2) the words “a misdemeanour”. and by omitting the words “of this Act and” in section 23(1). 3 In section 52, as it applies outside England and Wales, for the words from “be guilty” onwards there shall be substituted the words “be guilty of a misdemeanour and be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years”. -

Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality? Chen Yehudai

Marquette Law Review Volume 92 Article 6 Issue 4 Summer 2009 Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality? Chen Yehudai Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Chen Yehudai, Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality?, 92 Marq. L. Rev. 779 (2009). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol92/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATIONAL BLACKMAIL: SURVIVED BY TECHNICALITY? CHEN YEHUDAI Blackmail constitutes one of the most intriguing puzzles in criminal law: How can two legal rights—i.e., a threat to disclose true but reputation-damaging information and, independently, a simple demand for money—make a legal wrong? The puzzle gets even more complicated when we take into account that it is not unlawful for one who holds embarrassing information to accept an offer of payment made by an unthreatened recipient in return for a promise not to disclose the information. In order to answer this question, this Article surveys and analyzes the development of the law of informational blackmail and criminal libel in English and American law and argues that the modern crime of blackmail is the result of an “historical accident” stemming from the historical classification of blackmail as a property offense instead of a reputation-protecting offense. The Article argues that when enacted, the prohibition on informational blackmail was meant to protect the interest of reputation as a supplement to the law of criminal libel. -

Marian Allsopp Dissertation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online INVISIBLE WOUNDS: A GENEALOGY OF EMOTIONAL ABUSE AND OTHER PSYCHIC HARMS INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER This dissertation is about how the concept of harm, damage or wound is applied as a metaphor to a site often called the self or the soul. This is the social space of the individual subject, which is, paradoxically, placed by our language and culture in a person’s interior – a place where we are all said to be vulnerable and endangered by a potentially hostile environment. The thesis consists of a series of studies which are designed to show how the concept of harm to an inner life emerges from different discursive contexts, and how it does so in distinctly variable versions: psychological, emotional, neurological or social, in more or less stable hybrid forms. Using primary sources which are mostly documentary, supported by some interviews, the studies range from a look at the psychiatric history of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and at the story of its rewriting in English tort law; the recent reprised popularity of attachment theory and its marriage to neurology and a look at the career of the concept of the emotional abuse of children as a social problem category in the legal/administrative processes of Child Protection. These are introduced by a first chapter which concentrates on the metaphoric content of invisible wounds or psychic trauma 11 and the way it produces particular forms of the self. The studies which follow this are clustered around the literature and practices of the psychiatric, psychological, psycho-analytic, social work and legal professions, in order to show how the work of these professionals makes the concept of a psychic injury visible, discussible, treatable, administrable and justiciable.